- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1967 Topps Mets Maulers

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Mets Maulers

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

With a new year comes a whole new set of Card Corners, allowing us to delve into some previously undiscussed areas of baseball card history.

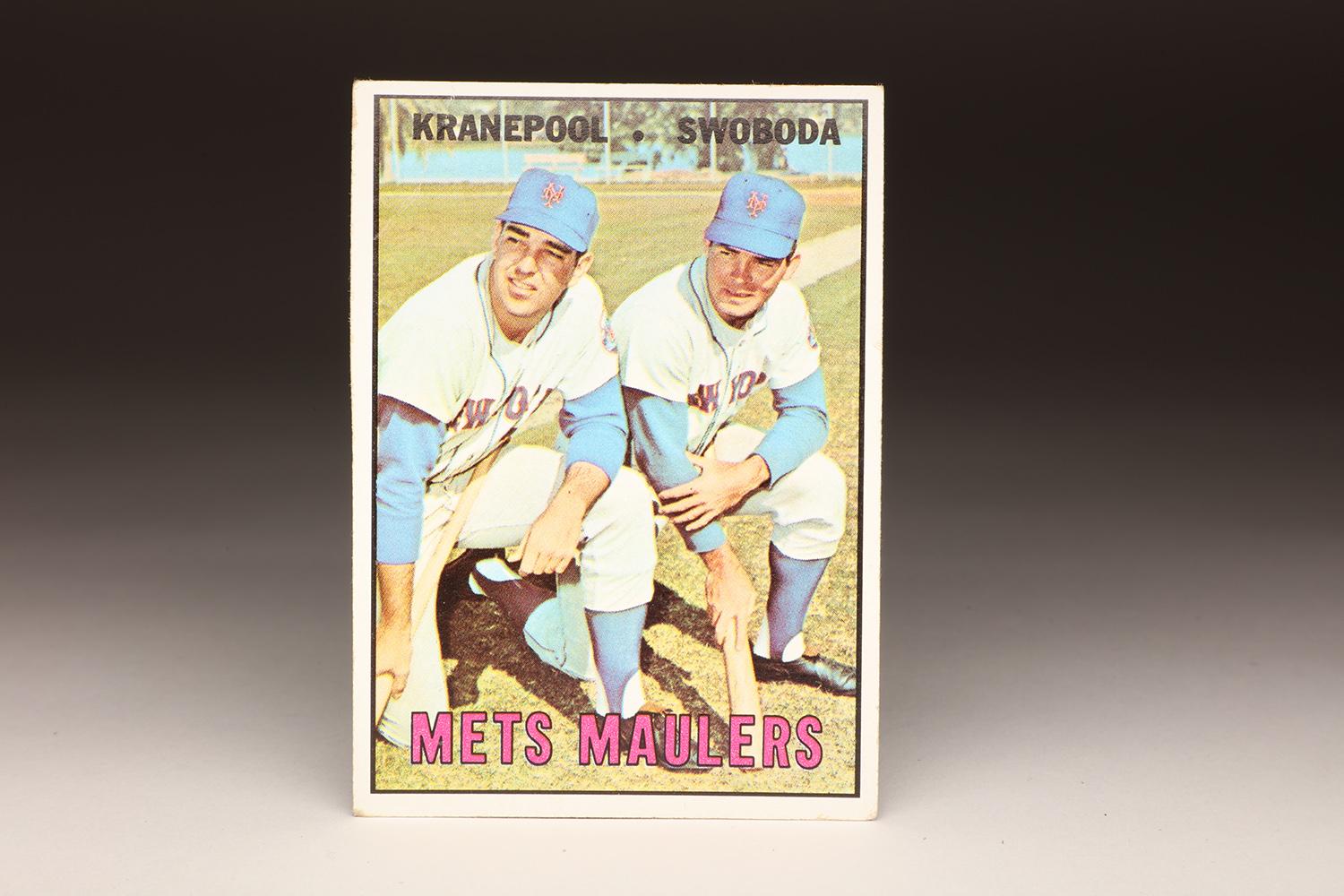

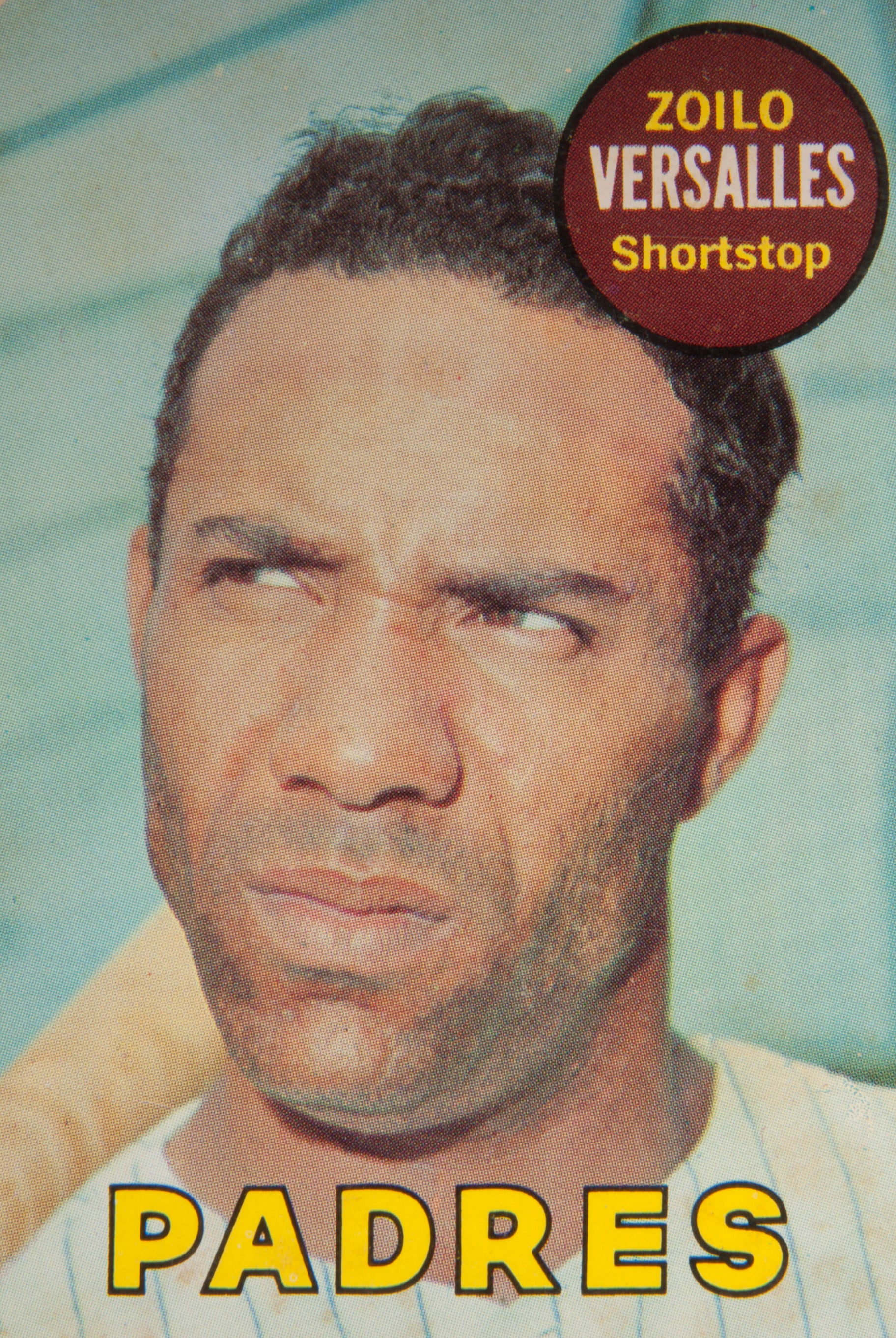

Since this is 2017, it also happens to mark the 50th anniversary of Topps’ 1967 card set. It is a set that deserves applause for its simplicity. There are virtually no design features to the card, no banners, no flags, no silhouettes, no unusual backgrounds. The photograph takes up most of the face of the card, except for the thin white border at the edges. The only prominent design element is the team name, in large letters, seen at the bottom of the card. At the top of the card, we see the player’s name and position in very small lettering, almost as if it were an afterthought.

For some fans, this might be too little in the way of design. There is really nothing that catches the eye. But for some fans, the lack of clutter allows the photography to shine, while also maximizing the space of the card. And isn’t that what baseball cards are all about, with an emphasis on the player and what he looks like?

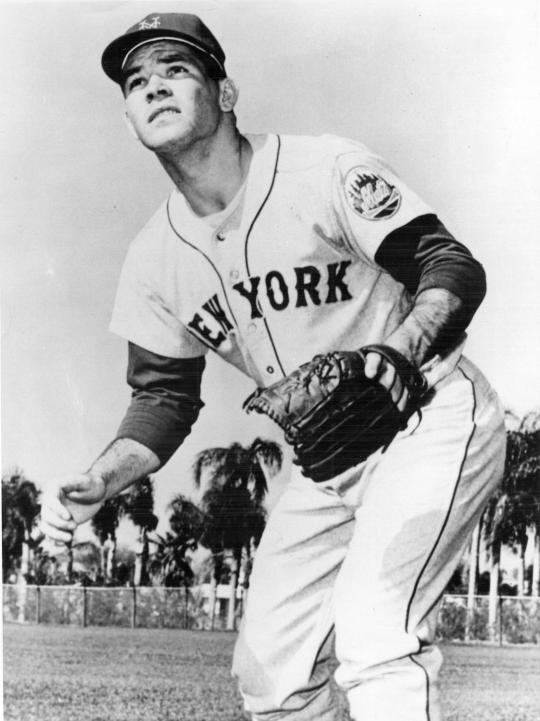

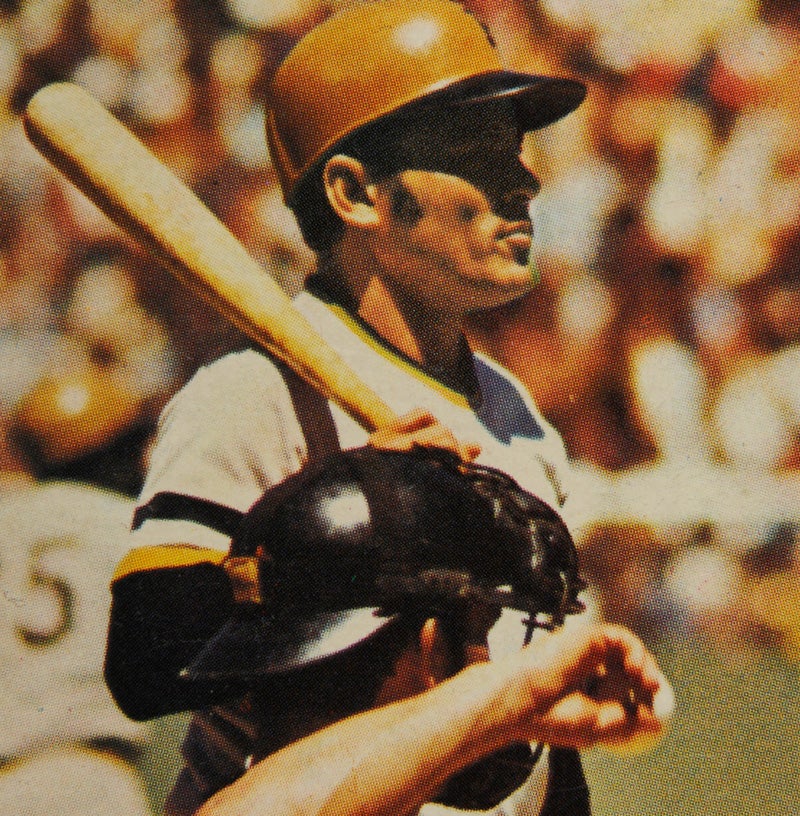

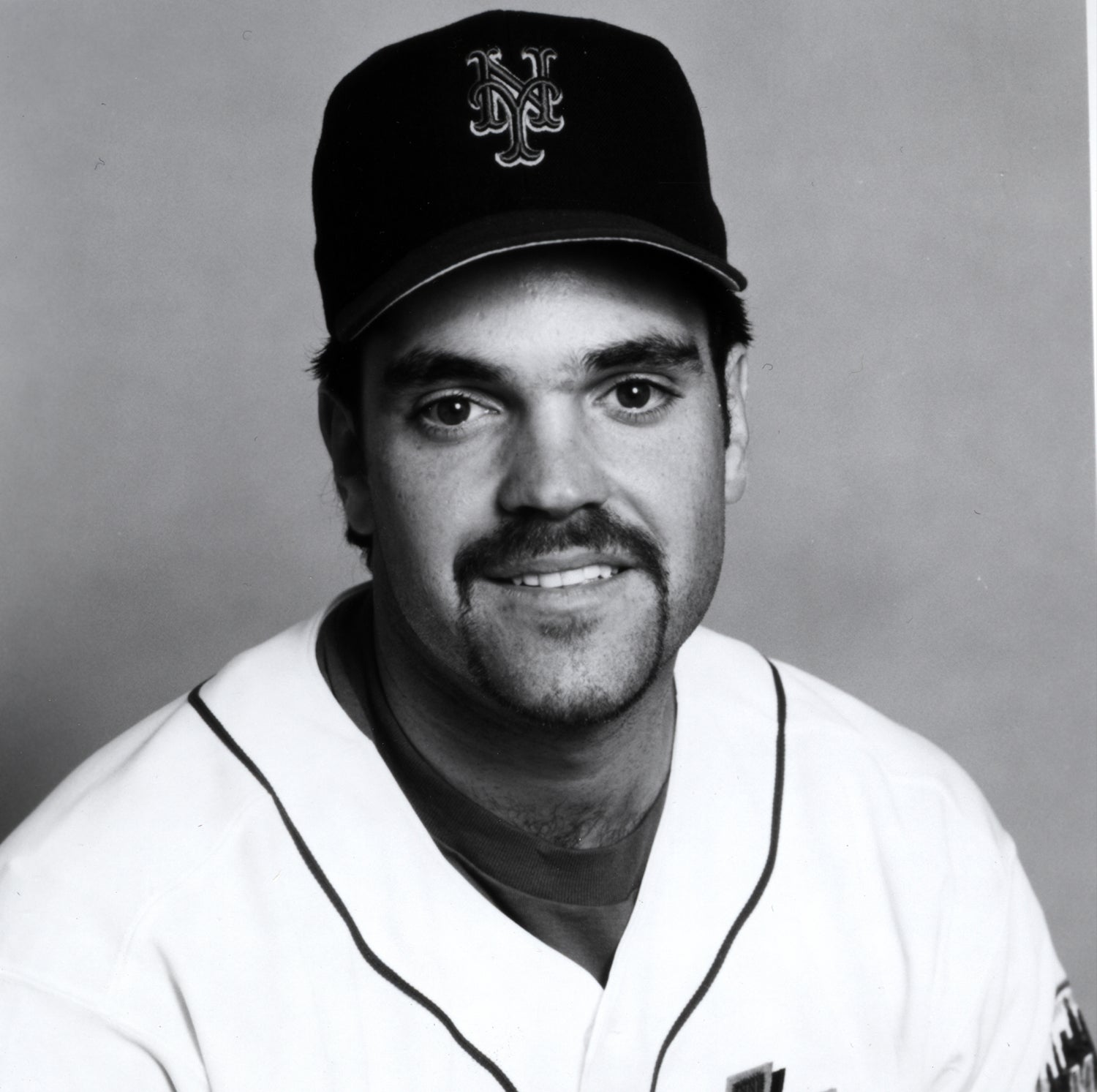

As part of the 1967 set, Topps issued a series of “combination cards,” featuring two or more players from the same team. One of those cards placed the spotlight on two everyday players for the New York Mets: Ed Kranepool and Ron “Rocky” Swoboda. Taken during Spring Training somewhere in Florida, the photograph shows the two players looking relaxed as they lean on their bats in a kneeling position. It’s the kind of card that makes you long for the warm days of a Florida spring.

The design of this card is similar to the base cards in the 1967 set, with two exceptions. First off, Topps replaced the team name with an alliterative headline at the bottom, in this case “Mets Maulers.” And at the top of the card, we see only the last names of the players, listed as “Kranepool” and “Swoboda.” This was a rather unusual feature for Topps cards, which have almost always listed the players’ first and last names on the front of the cards.

The back of Mets Maulers also gives us something different. As collectors, we’re used to seeing lots of numbers on the backs of cards, usually in the form of both seasonal and lifetime statistics. In the case of Mets Maulers, the back of the card takes on a narrative form. It’s a solid paragraph of writing, one that tries to tell the story of Kranepool and Swoboda in capsule form. It’s certainly a different look for the back of the card, and a refreshing one at that, given the emphasis on statistical information that sometimes overloads our game.

While it’s timely to note the 50th anniversary of cards like Mets Maulers, it’s also worth noting that both Kranepool and Swoboda visited Cooperstown last summer. They came to town for Hall of Fame Weekend, in part to sign autographs for one of the memorabilia shops on Main Street. As it happens, my family had the chance to meet the two former Mets.

Frankly, I had little to do with their encounter. It was really the doing of my enterprising 10-year-old daughter, Madeline. She wanted to do something nice for one of our neighbors, Bill, a longtime Mets fan, during the weekend that saw Mike Piazza officially enter the Hall of Fame. We found out that one of the Main Street shops was hosting a reunion of sorts for the 1969 Mets, with Kranepool, Swoboda, Cleon Jones, and Art Shamsky all appearing simultaneously. I told Maddie that we could get two autographs, so Maddie called up Bill’s wife, Mary Lou, and asked her which of the four he would like. With little hesitation, Mary Lou said, “Ed Kranepool and Ron Swoboda.”

As it turns out, all four of the former Mets were there on Saturday afternoon. Maddie and my wife Sue paid for the autographs, but they informed me that all four players were cordial and friendly, even those whose autographs we did not obtain. That’s something I’ve noticed about retired ballplayers, particularly those from the 1960s and 70s: They always seem appreciative that someone takes an interest in their careers, regardless of whether they stand to benefit financially. When fans show that they care, these players respond in kind.

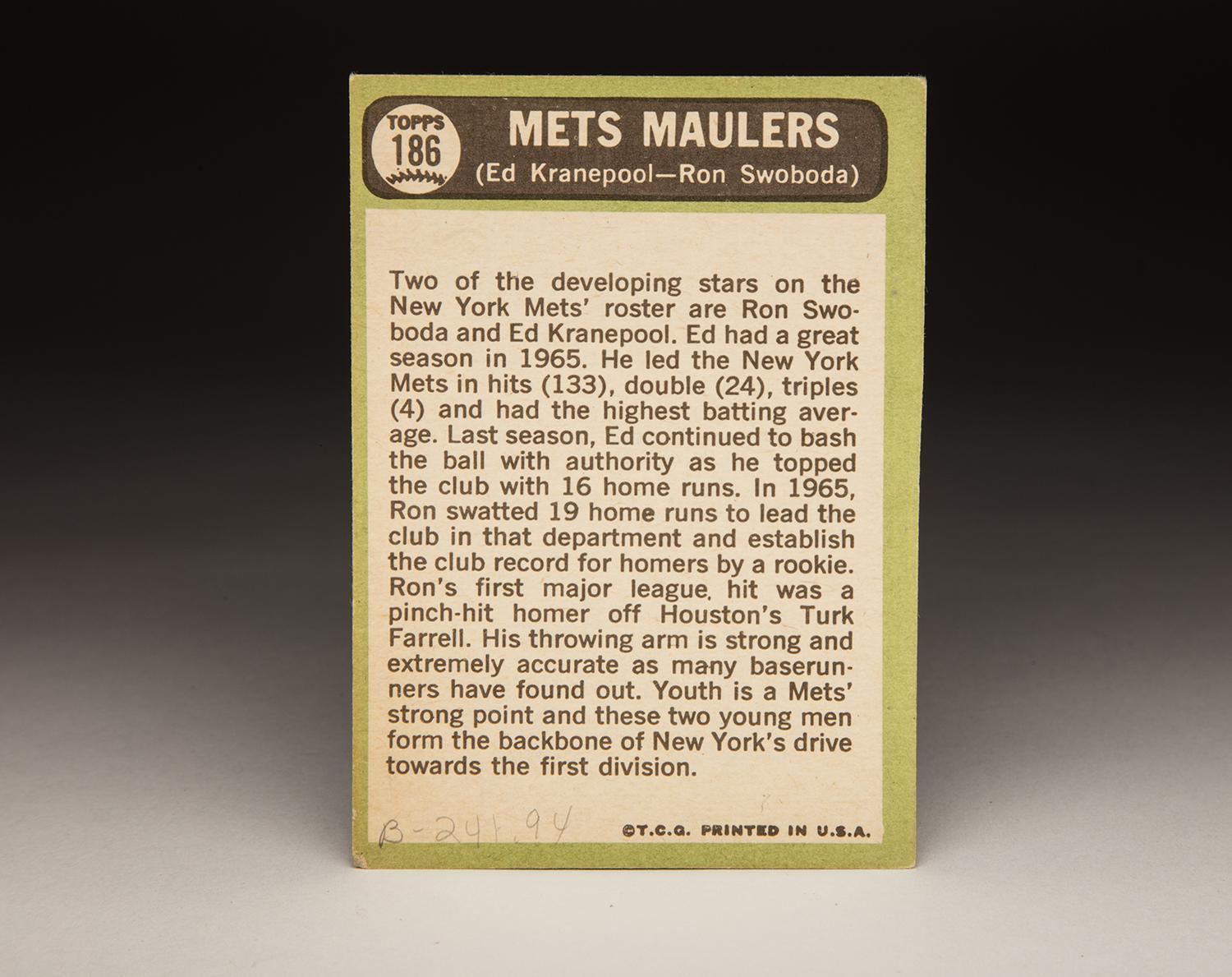

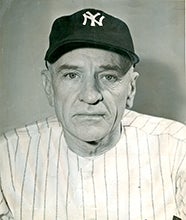

Kranepool and Swoboda, while never stars, were just the kinds of players that Mets fans cared about during the franchise’s early years in the 1960s. A graduate of James Monroe High School in the Bronx, Kranepool signed with the Mets at the age of 17 and appeared in three games for the original Mets of 1962. In 1963, Kranepool spent a little bit more time in New York, but also found himself caught in the middle of a minor dispute involving two Hall of Famers. Kranepool’s manager, Casey Stengel, wanted him to hit the ball to all fields. So one day, Kranepool stepped into the batting cage and consciously tried to hit the ball to the opposite field. One of his teammates, elder statesman Duke Snider, noticed the tendency and scolded Kranepool, telling him to pull the ball. The two players exchanged angry words, with Kranepool explaining that he was following the orders of his managers. Ultimately, the Stengel philosophy won out.

After a 15-game stint at Triple-A to start the 1964 season, Kranepool found himself in the major leagues to stay. Stengel made him his starting first baseman and watched him hit .257 with 10 home runs in 119 games. Those weren’t great numbers, but Kranepool’s body of work did represent an improvement over the first regular first baseman the Mets had ever used: The inimitable Marvelous Marv Throneberry.

In 1965, Kranepool made the National League’s All-Star team, though that designation resulted in large part because of the necessity that every team be represented in the Midsummer Classic. By the end of the 1965 season, Kranepool’s numbers actually fell short of his 1964 standard, but they were still good enough to keep him at No. 1 on the Mets’ depth chart at first base.

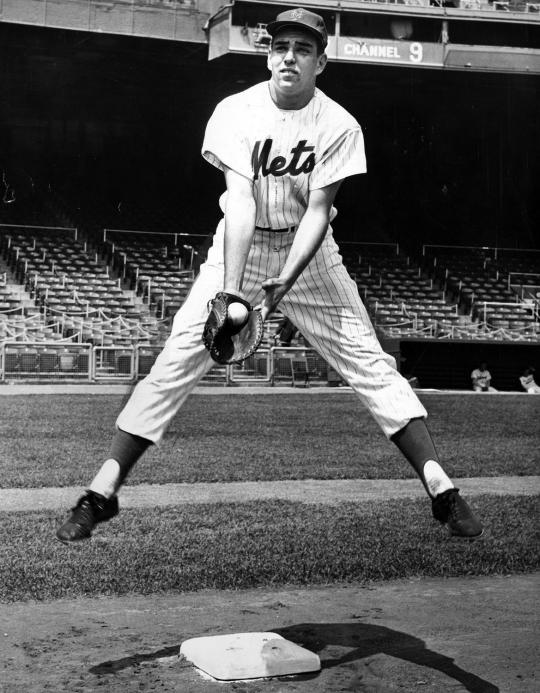

Swoboda’s arrival in New York came later than Kranepool’s, but was less fragmented. After spending just one season in the Mets’ farm system, the Baltimore native earned a promotion to New York in 1965 and moved right into the starting lineup. Playing in right field, Swoboda produced mixed results. He hit with power (19 home runs) and showed off a good throwing arm, but he struggled in the art of reaching first base. With a batting average of just .228 and with an overly aggressive approach at the plate, Swoboda reached base only 29 percent of the time. In the outfield, he made a number of mistakes. His defensive play was so spotty that he would become known as “Rocky.”

Swoboda’s rookie season also involved an incident that bordered on the comical. It was an incident that I once wrote about, but didn’t have all of my facts in order. Here’s what I initially wrote:

On May 23, 1965, Ron Swoboda takes his position in right field wearing a batting helmet on his foot. The reason? After an unsuccessful at-bat, Swoboda tries to kick his helmet, only to get his foot stuck. Unable to remove the helmet, Swoboda is ordered to take the field by manager Casey Stengel.

Well, that turned out to be wrong, as I found out when I interviewed Swoboda on MLB Radio shortly thereafter. He told me that he did stomp on his helmet, and did momentarily get his foot stuck in the helmet. But Stengel did not tell him to take his place in right field while wearing the helmet on his foot. Instead, Stengel did the opposite, taking Swoboda out of the game and ordering him to go to the clubhouse. Stengel was unhappy with his rookie outfielder’s show of temper and felt that he needed to be disciplined for it. A check of the boxscore for that day supports Swoboda’s claim. Swoboda was indeed removed from the game, replaced by Johnny Lewis.

While Swoboda’s temper bothered Stengel, it didn’t upset Mets fans, who quickly took to the fiery outfielder. Fans at Shea Stadium, who loved Swoboda’s emotional approach to the game, buzzed whenever Swoboda stepped into the batter’s box.

In 1966, the year on which the Mets Maulers card was based, Swoboda and Kranepool both played regularly for the Mets. Kranepool led the Mets with 16 home runs while posting an OPS of .715, which was respectable for the time. But Swoboda struggled.

He hit only eight home runs, batted .222, and compiled an OPS of .638. In reality, Swoboda didn’t do much “mauling.” Even as a tandem, Swoboda and Kranepool hardly ranked as one of the top hitting duos in the National League.

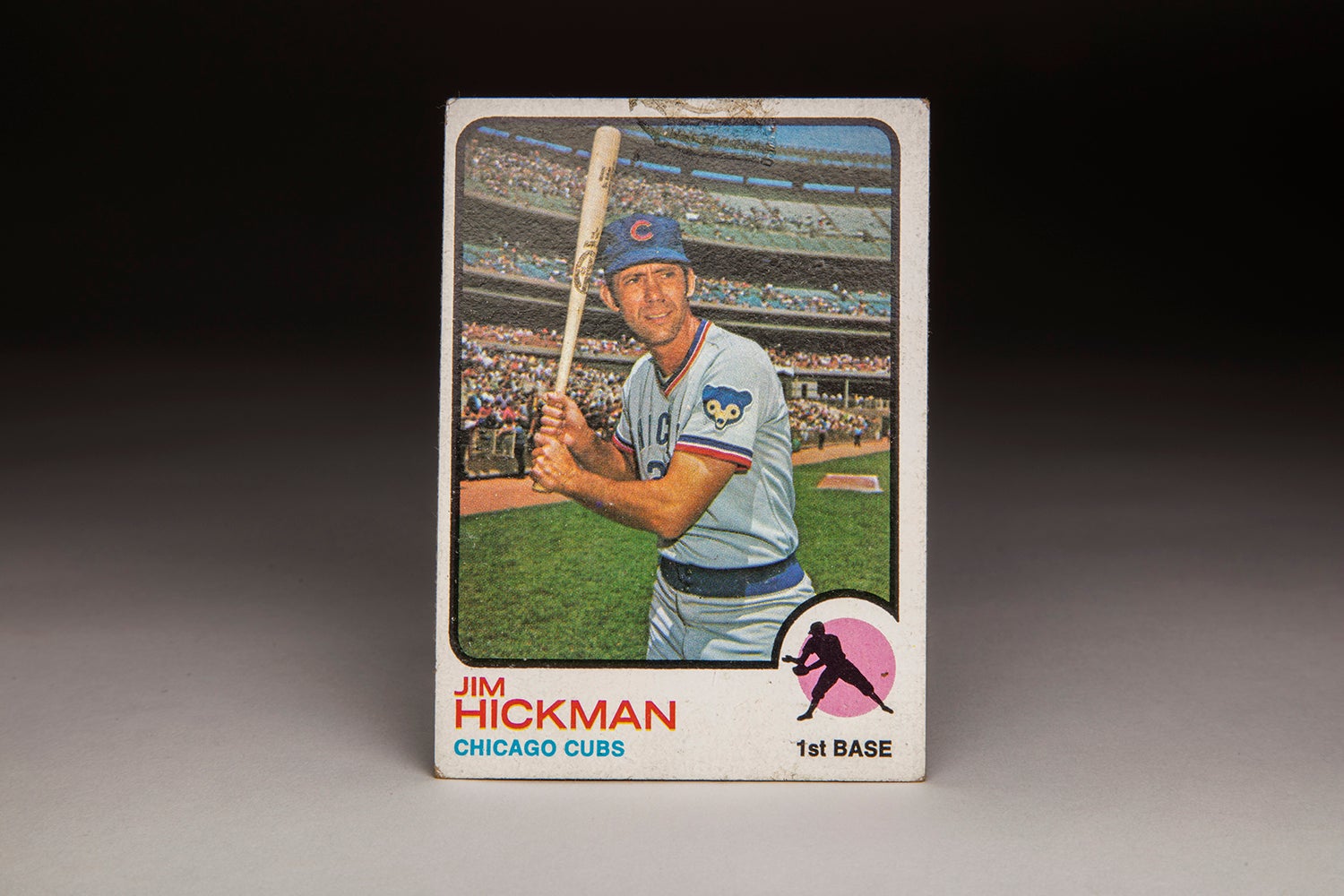

So why did Topps see fit to put out a card called Mets Maulers? All these years later, I’d have to guess that Topps, whose offices were located in Brooklyn at the time, wanted to include a card that centered on the Mets. Besides, the Mets had already developed a strong fan following in their early years. Given a preference for the Mets, Topps did not have much to choose from with regard to marquee talent. A more logical choice might have been Ken Boyer, who hit 14 home runs in 1966 and led all Mets regulars with an OPS of .719. But Boyer was also 35 years old and nearing the end of his career. Early in 1967, the Mets would trade Boyer to the Chicago White Sox for infielders Sandy Alomar and Bill Southworth. So in retrospect, Boyer might not have been the best choice either.

While we might wonder about the presence of Kranepool and Swoboda on a card called Mets Maulers, their choices turned out to be prescient and prophetic in some ways. One year later, in May of 1968, Sports Illustrated added to Swoboda’s fame by featuring him on the cover of its magazine. And then a year after that, Swoboda and Kranepool would both play key roles in helping the Mets win the world championship. Kranepool spent much of the 1969 regular season platooning with Donn Clendenon, giving the Mets some needed left-handed punch on a team that titled heavily to the right.

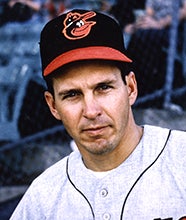

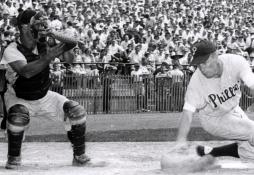

In the meantime, Swoboda didn’t hit much while platooning with Art Shamsky during the regular season, but delivered in a major way during the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. At the plate, Swoboda stroked six hits in 15 at-bats, even more impressive considering the quality of the Orioles’ pitching staff. In the field, Swoboda turned in what some observers have called the finest catch in World Series history. It came in the ninth inning of Game 4, with the Mets holding on to a 1-0 lead. With runners on first and third, Brooks Robinson smashed a low liner into right-center field that seemed destined to split the gap and bring home both the tying and go-ahead runs. Out of nowhere, Swoboda raced toward the gap and threw his body at the ball. With his body fully extended and his glove just inches from the ground, Swoboda caught the ball backhanded and then held on after landing hard on the outfield grass. The Orioles did score the tying run on the play, but Swoboda’s heroics preserved the tie, allowing the Mets to rally and win in the bottom of the 10th.

Without question, that play became the signature of Swoboda’s career with the Mets. After another difficult regular season in 1970, the Mets decided to part ways with their World Series hero, sending him to the expansion Montreal Expos for a younger outfielder, Don Hahn. Lasting only 39 games with Montreal, Swoboda soon moved on to the New York Yankees in a trade for fellow outfielder Ron Woods. For the next two and a half seasons, Swoboda played a part-time role for the other New York team, before being released after the 1973 season. Just 29, Swoboda would never play again.

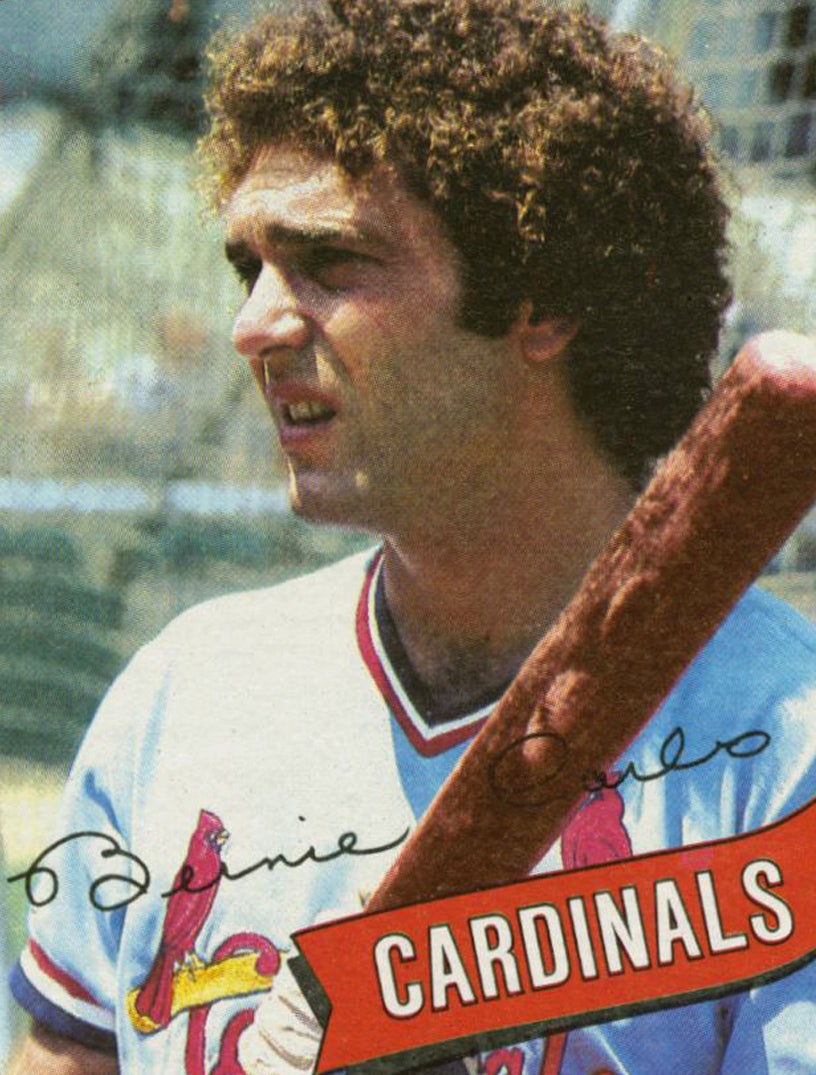

His on-field career over, Swoboda found success as a broadcaster, doing work at the local level for TV and radio stations in New York, Phoenix, and New Orleans. He also opened up a restaurant, which he co-owned with none other than Kranepool, his onetime Topps partner and close friend. The two became involved in several business associations, including a food company and a stock market venture.

At one point, none of that would have seemed possible. In the mid-1960s, there had been tension between the two players, in part because of their contrasting personalities. Swoboda’s outgoing, affable manner ran opposite of Kranepool’s short-tempered personality. Kranepool became jealous of Swoboda’s popularity. But that all changed. The two players became roommates, and a friendship followed. In fact, Kranepool and Swoboda had such a wild time rooming together that the Mets later decided to break them up, fearful that they were having too good a time.

In 1999, Swoboda and Kranepool re-entered the public spotlight when they (along with Tommie Agee) made memorable appearances as themselves on the hit comedy, Everybody Loves Raymond. The show’s star, Ray Romano, has long been a Mets fan, spurring his interest in bringing the team’s alumni onto the show.

While Swoboda’s career with the Mets lasted seven seasons, Kranepool’s time in New York encompassed his entire career. There were a number of highlights. In 1971, he put together his best season, hitting .280 with 14 home runs. In 1974 and ’75, he hit .300 or better while drawing more walks than strikeouts. He also played for the Mets’ pennant-winning team in 1973, though he did not play particularly well as the backup to John Milner at first base.

Kranepool remained with the Mets for the rest of the 1970s, finally retiring at the end of 1979. For a player who was never a star, and who usually filled a role as a platoon player, it’s rather remarkable that Kranepool played exclusively for one team over a span of 18 seasons. It’s partly a reflection of the fact that most of Kranepool’s career took place in the era before free agency. If Kranepool had become a free agent in his prime, he might have left to sign with a team that could give him an everyday job.

Another factor was Kranepool’s popularity. He was an original Met, having made three appearances for the team in 1962, and remained a fixture throughout the down years of the 1960s, the miracle of 1969, and the mixed bag of results of the early 1970s. He also carried with him a never-ending connection to New York City. Born in New York, Kranepool had gone to school in the Bronx and continued to call New York his home throughout his Mets career. He never lost those New York City roots, something that Mets fans always appreciated. “The Krane” was one of them.

All of these years later, older Mets fans continue to hold a special place for both Kranepool and Swoboda. They remain ambassadors to the early days of the Mets’ franchise, both to the lean years under Stengel and the miracle of 1969, and their friendship continues to be strong. While the statistically inclined might poke fun at a card pairing them as “Mets Maulers,” it turns out that the Topps Company knew exactly what it was doing when it decided to pair Rocky and The Krane on the same baseball card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame