- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

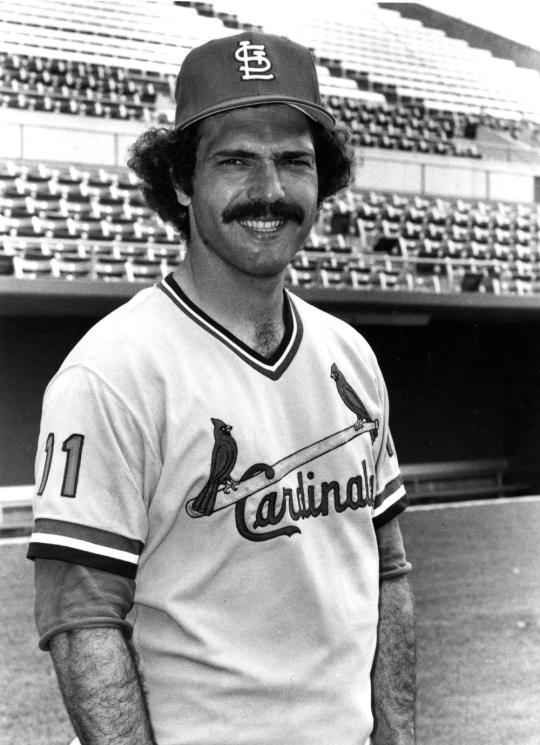

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

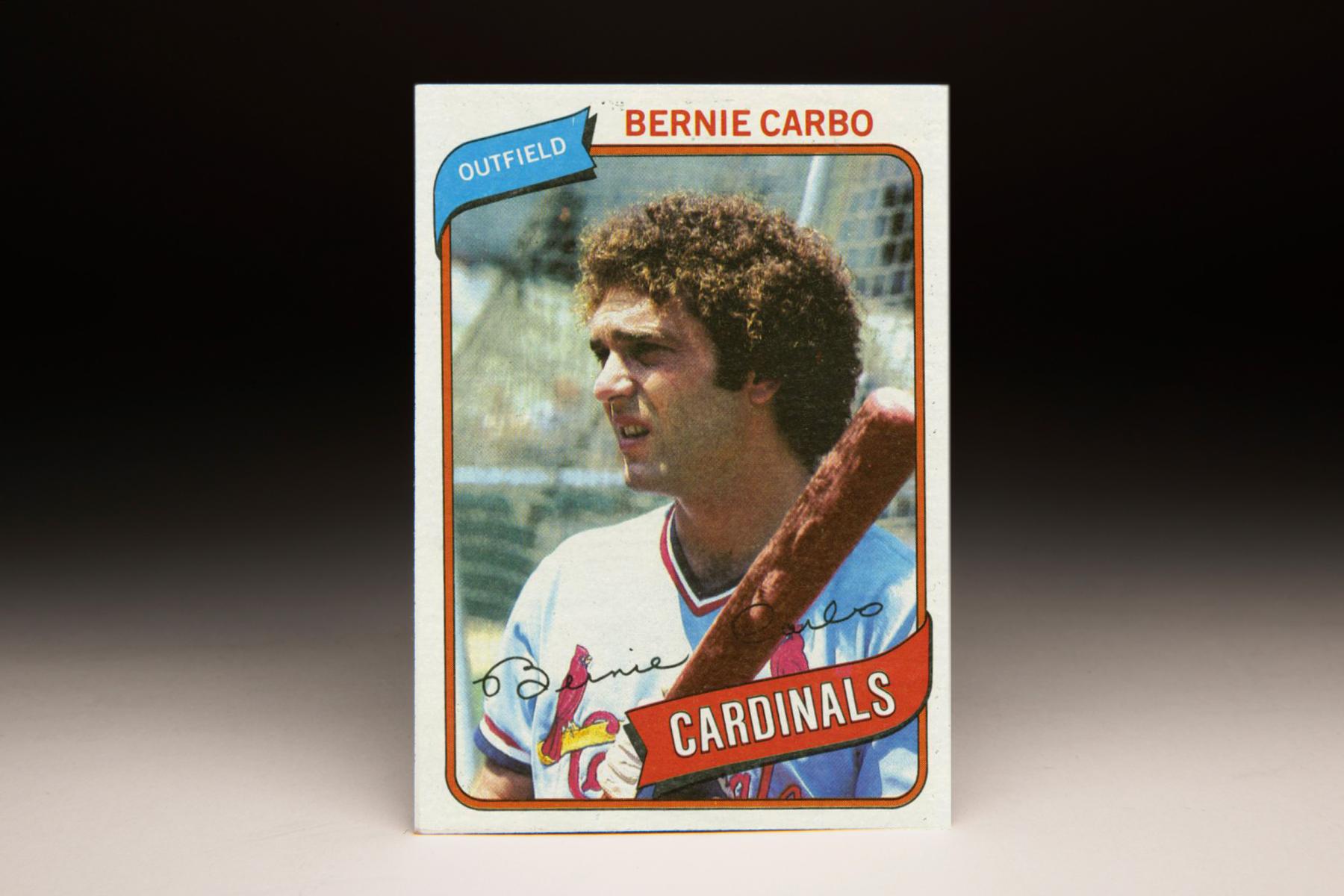

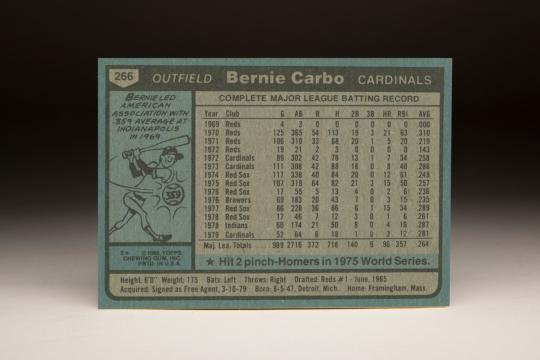

In 1980, the Topps Company gave us this final impression of Bernie Carbo, a veteran outfielder who was wrapping up his career with the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates, two teams that were plagued by cocaine use. By May of 1980, the card had become somewhat obsolete. That’s when the Cardinals released Carbo, who then finished out the season with the Pirates before drawing a second release in October. In June of 1981, Carbo would sign a minor league deal with the Detroit Tigers (his hometown team), but would never make it back to the big leagues. The 1980 card would be his swansong, his last appearance on cardboard.

It might have been his final Topps card, but it was a memorable one. There’s a lot going on with this card, beginning with that wonderful hairstyle that Carbo is sporting. Perms were popular back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and Carbo was one of many players who opted for that look. It was especially fitting for Carbo, who at the time expressed interest in becoming a hairdresser. More on that later.

Next up is the bat that Carbo is holding. The bat is positively filthy, slathered in what appears to be either mud or pine tar. I’m guessing that it is pine tar, and if it is, the bat would have been illegal, since the pine tar clearly exceeds the 18-inch limit. Only three years after this card came out, Hall of Famer George Brett would make that obscure pine tar rule famous with his home run against Goose Gossage, accomplished with a bat that also had more than 18 inches worth of pine tar.

Finally, let’s take note of Carbo’s facial expression on the card; it could be interpreted as anything from simple preoccupation to a feeling of being dazed. The latter feeling would be especially appropriate for a player like Carbo, an unpredictable character who often acted dazed and out of sorts, sometimes because of the drug culture that became so prevalent in the 1970s. Thankfully, the card did not represent the final chapter for Carbo. In looking at it, one can smile now, knowing that Carbo would construct a happier outcome.

Born Bernardo Carbo in Detroit, Mich., he grew up in a difficult household, where his father was a mean-spirited and abusive alcoholic. At one point, Carbo was sexually abused by an older cousin. Not surprisingly, Carbo started drinking and became a full-blown alcoholic by his teenage years.

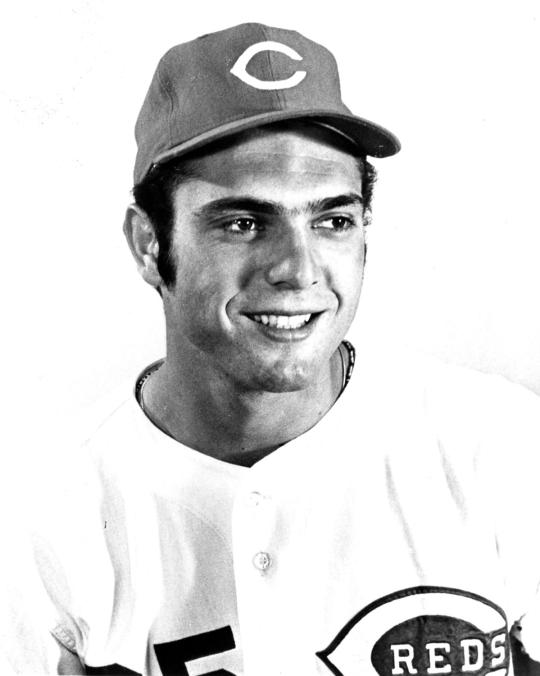

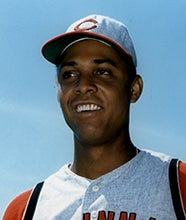

Despite his addictions, Carbo’s career looked like a direct path to stardom, at least early on. After a cup of coffee with the Cincinnati Reds in 1969, he played his first full season in 1970. Emerging as a platoon left fielder with Hal McRae on an early incarnation of the “Big Red Machine,” the lefty-hitting Carbo batted .310 with 21 home runs and 94 walks. Helping the Reds win the National League pennant, he finished second in the Rookie of the Year balloting, placing behind pitcher Carl Morton.

Just 21 years old, Carbo looked like he would become another star for the Reds, joining a constellation that already included Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Bobby Tolan and Pete Rose. It all came unraveled the following season, when Carbo’s batting average fell to .219 and his power dropped, as his home run total fell to five and his slugging percentage to .338. His drug use was part of the problem, as it took a toll on his body. His angry temper showed, as he became frustrated with his performance. Carbo’s offbeat behavior, which had earned him the nickname “The Clown” during his minor league days, also worried the Reds, an organization that preferred a button-down approach from its players.

A slow start to the 1972 season convinced the Reds to make a move; on May 19, they traded Carbo to the Cardinals for platoon first baseman Joe Hague. Carbo fared a bit better for the Cardinals than he had over the past year and a half in Cincinnati. In 1973, he posted a respectable OPS of .819 as a platoon right fielder, but he also fell well short of the standard that he had set as a superstar rookie. Worried that his career was stalling, the Cardinals decided to package him and right-hander Rick Wise in an offseason trade with the Boston Red Sox, sending the pair to Beantown for outfielder Reggie Smith and reliever Ken Tatum.

Not long after that trade, Carbo received a stuffed gorilla from former Cardinals teammate Scipio Spinks, a right-handed pitcher of some promise. Carbo’s new stuffed animal earned the name “Mighty Joe Young,” in honor of the legendary film character from the 1949 film of the same name. When on road trips, Carbo did not want to travel without his new “friend,” so he took his companion with him. To ensure that his pet “gorilla” would remain by his side, at restaurants and movie theaters, Carbo often paid for an extra ticket. For Carbo, it was well worth the expense.

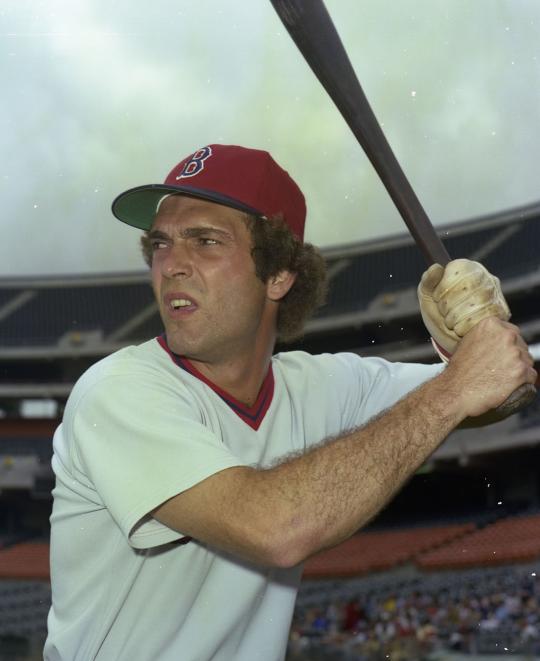

It was with the Red Sox that Carbo began to fully develop a two-tiered reputation within the game. On the field, he became a solid platoon player and pinch-hitter. Off the field, he tended to behave in a bizarre fashion, sometimes lacking in awareness of his surroundings. Shortly after becoming a member of the Red Sox, Carbo was in the Fenway Park clubhouse one day when he noticed an older man whom he presumed to be one of the clubhouse attendants. Carbo gave the man a $20 bill and asked him to fetch a cheeseburger and fries from one of the concessionaires. Carbo apparently didn’t realize that the man was actually Red Sox owner and Hall of Famer Tom Yawkey.

One of Carbo’s most colorful episodes took place on June 26, 1975, as the Red Sox played the rival New York Yankees at Fenway Park. Carbo made a daring catch in front of the right-field wall, robbing Chris Chambliss of a home run. Carbo crashed into the wall, somehow escaping injury but managing to lose the chaw of tobacco he had in his mouth. Carbo then asked umpires for time, so that he could search the outfield for the missing chaw. After holding up the game for several minutes - and it’s not exactly clear why the umpires even allowed the delay - Carbo finally found the tobacco lying in a heap on the warning track. He picked up the chaw of tobacco and put it right back into his mouth, in full view of the fans watching from the right field bleachers.

That incident would become mostly forgotten by October, as the Red Sox won the division and the pennant, earning the right to play Carbo’s first team, the Reds, in the World Series. Carbo spent most of the Series on the bench, until being summoned by manager Darrell Johnson to pinch-hit in the eighth inning of Game 6. With two men on and the Red Sox trailing by three, Carbo stepped in against hard-throwing Reds reliever Rawly Eastwick. After battling through a long at-bat where he nearly struck out on a ball in the dirt, Carbo belted a fastball to straightaway center field, up and over the Fenway Park wall. The home run, estimated to be at least 420 feet, tied the game up, setting the stage for Carlton Fisk’s dramatic game-winner in the bottom of the 12th.

Carbo’s home run represented the peak of his Red Sox career. No one could have known that only a handful of games into the 1976 season, the Sox would trade Carbo, sending him to the Milwaukee Brewers in May for a package of outfielder Bobby Darwin and right-hander Tom Murphy. It was an unpopular trade right from the beginning, unwanted by fans and other Red Sox players.

Realizing their mistake, the Red Sox corrected the measure that October, reacquiring Carbo from the Brewers as part of a deal for Cecil Cooper. Carbo would remain with Boston through the middle of the 1978 season, when Red Sox owners Haywood Sullivan and Buddy LeRoux allegedly hired a private eye to follow him around. They soon determined that Carbo was using drugs. Another problem was Carbo’s membership in the “Buffalo Heads,” a small group of Red Sox players who mocked manager Don Zimmer. Deciding that Carbo was a bad actor, the Red Sox sold his contract to the Cleveland Indians. At season’s end, he became a free agent, signing with the Cardinals.

After the end of his baseball career, Carbo took an unusual path, at least for a former ballplayer. He went to cosmetology school for two years, earned his license, and began operating a hair salon in Detroit. Carbo enjoyed some success with the business, which lasted for eight years, but those efforts were derailed by his continuing problems with drugs and alcohol.

Carbo had managed to keep his drug problems quiet for much of his playing career, but he would talk about them openly many years later. Even at the height of his big league days, when he launched that titanic home run against Eastwick, Carbo was fully under the influence. “[That day] I probably smoked two joints, drank about three or four beers, got to the ballpark, took some [amphetamines], took a pain pill, drank a cup of coffee, chewed some tobacco, had a cigarette, and got up to the plate and hit,” Carbo told The Boston Globe in 2010. “I played every game high. I was addicted to anything you could possibly be addicted to.”

Not only did Carbo take drugs, but he also began dealing them in his post-baseball days, leading to additional problems. His situation reached rock bottom in the early 1990s, when his wife divorced him, his mother committed suicide, and his father also passed away. Carbo himself thought about taking his own life.

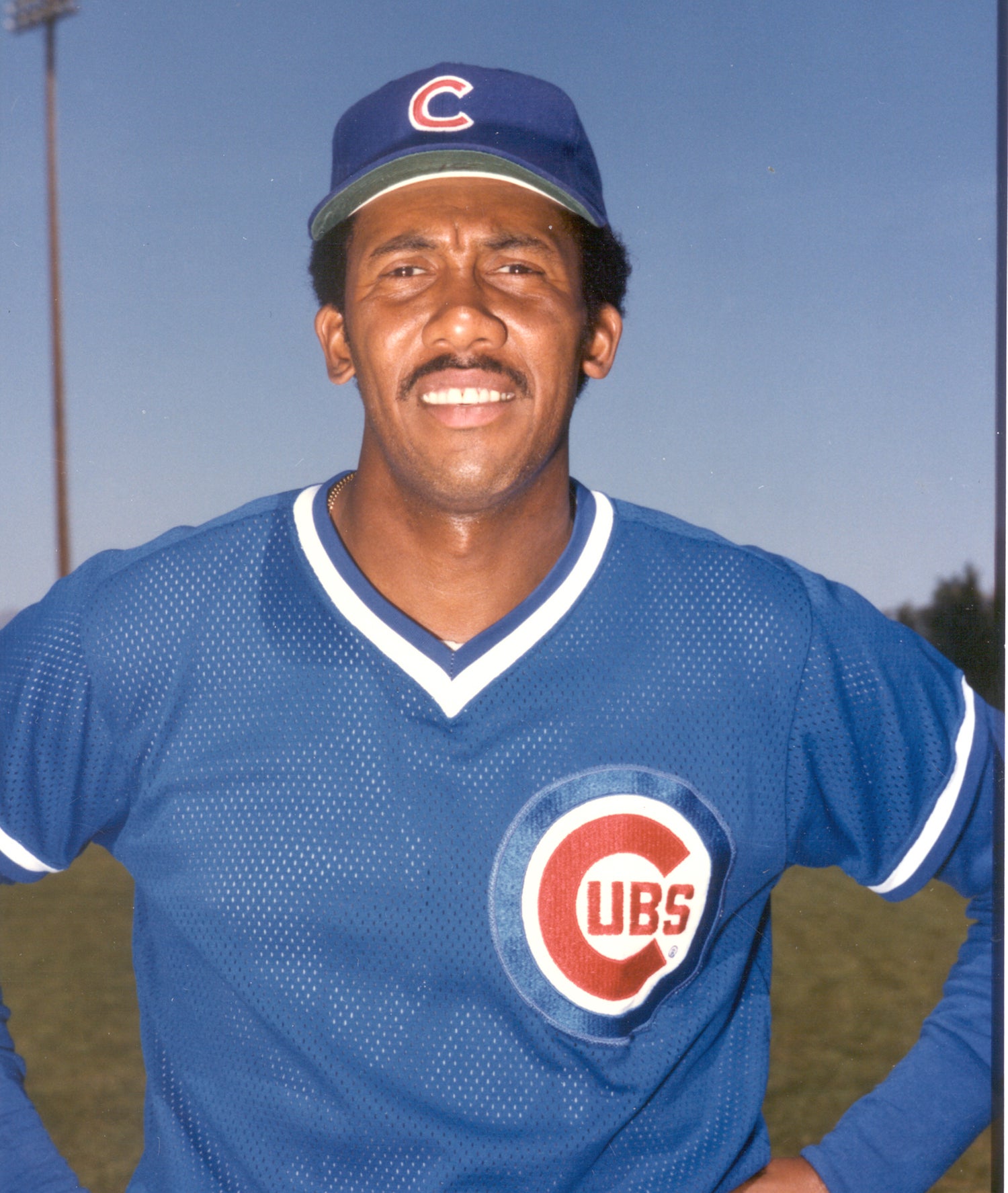

Thanks to the efforts of former teammates like Ferguson Jenkins and Bill Lee, Carbo found help. They put Carbo in touch with Sam McDowell, the former major league pitching star who had become a counselor for the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT). McDowell (a recovered alcoholic himself) and BAT arranged for Carbo to enter a rehabilitation center. During his time in rehab, Carbo learned about Christianity and began to embrace the values of the religion.

Since his successful stint in rehab, Carbo has founded a Christian ministry, become a motivational speaker, and remarried. He also became a minor league manager for three seasons, but decided to leave the game so that he could concentrate on his ministry. His only current connection to the game is the fantasy camp that he runs each year in Mobile, Ala. He says that he has not used drugs or alcohol since 1995.

Carbo is doing well these days, but that doesn’t mean that every aspect of his life has been easy. He watched his three daughters land in prison because of their involvement with selling drugs and writing bad checks. He adopted his three grandchildren, who are now in the custody of Carbo and his second wife. His efforts to gain custody stirred debate, with some critics claiming that his past involvement with drugs and alcohol should have disqualified him from adoption. The courts thought differently, ruling in favor of Carbo.

I find myself rooting for Carbo. Well-liked by his teammates, he contributed to some very good teams in Cincinnati and Boston. He brought some life to the clubhouses that he called home, adding offbeat color to the game in the 1970s. Most importantly, Carbo has come a long way since those thoughts of suicide and those dark days consumed by bottles of alcohol and vials of drugs. He speaks out against that lifestyle, hoping that youngsters will not repeat his mistakes. In rising from the depths of drugs that cast a haze on his 1980 Topps card, Carbo has found more than just redemption; he seems to have found legitimate comfort and satisfaction in his life.

With this baseball card comes a happy ending.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame