- Home

- Our Stories

- A Road to Equality

A Road to Equality

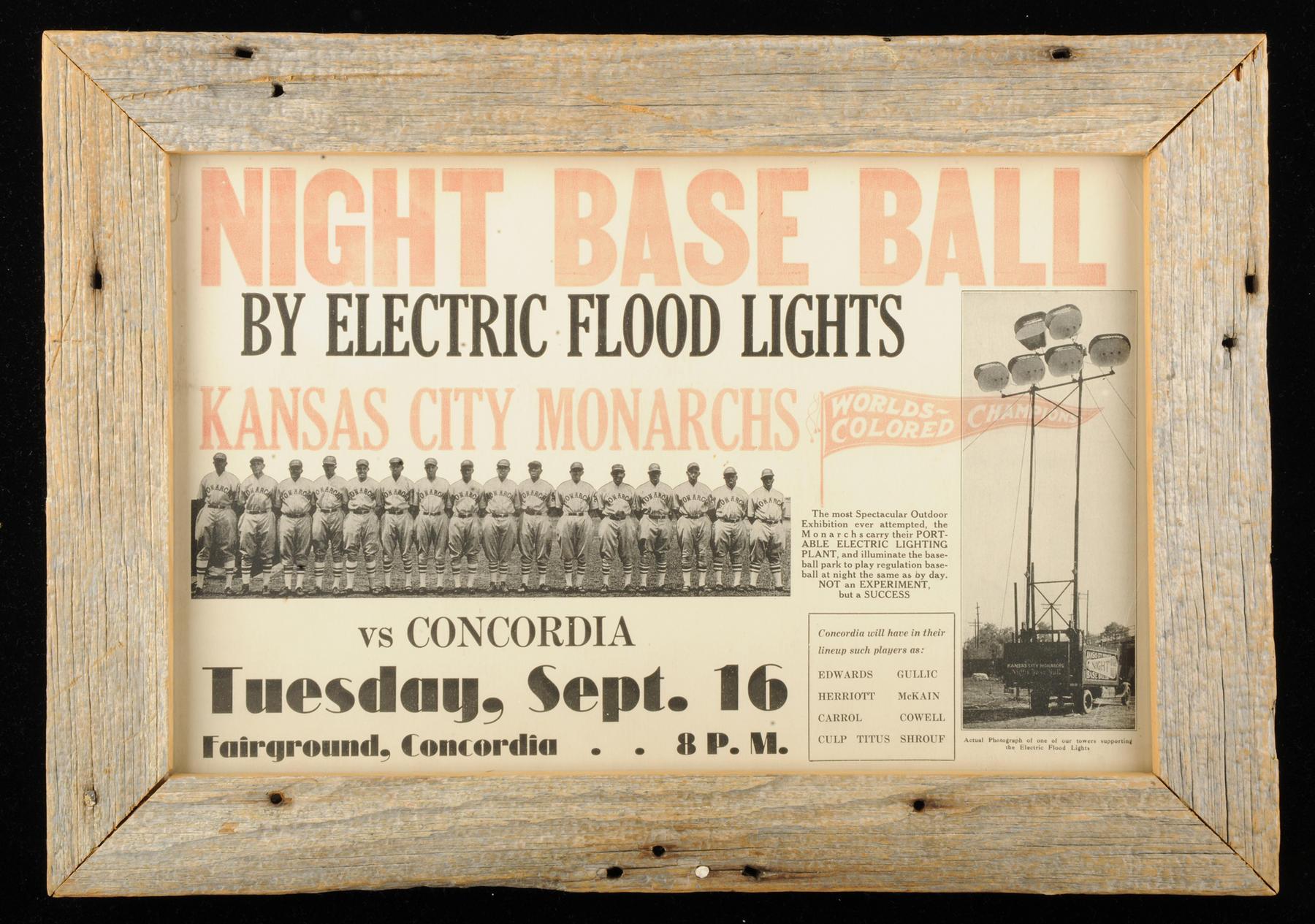

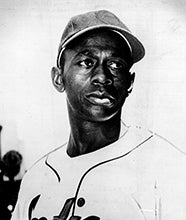

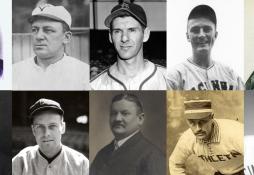

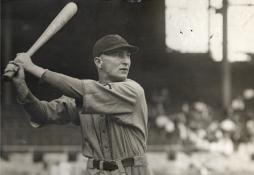

He was the nation’s ringer, a barnstorming industry unto himself who learned to pitch not by the week but by the hour. But while Leroy “Satchel” Paige was the best, he was hardly alone. For three generations of African-American baseball players, barnstorming was more of a full-time job than a part-time tour. They called the freewheeling freelance baseball they played across America barnstorming, to distinguish it from formal league games. Major Leaguers and Negro Leaguers both did it, but for the former it was restricted to the postseason whereas Black players squeezed in exhibitions year-round. The contests were set up by players, owners, or independent promoters, most of whom were white. Touring teams played each other or a local club. Admission was seventy-five cents, and five hundred spectators was a decent turnout. Players earned as much as $150 a day or as little as $15. Barnstormers dubbed themselves “All-Stars” although typically only two or three qualified. A more accurate description was Hungry Ball, since ballplayers needed the extra income to carry them through the year. Barnstorming brought baseball’s icons to small towns with no stoplights but lots of barns, and it gave hamlet heroes at least the fantasy that they might someday be discovered. In the East, games were fit in between the end of the World Series and the onset of winter; in the Midwest they were scheduled around the harvest; in California, Florida and the Caribbean they continued until spring.

Black players had been barnstorming since the 1880s, generally in the no-budget, rag-tag fashion that characterized the rest of their play – but sometimes in style. Bud Fowler’s All-American Black Tourists rented their own railroad car, and each game was kicked off with a parade led by players decked out in swallow-tail coats and opera hats and brandishing silk umbrellas. The American Giants entertained guests at Palm Beach’s Royal Poinciana Hotel.

More typical, Giants infielder Jack Marshall said, were monotonous road trips where he ate sardines out of a Bell Fruit jar and was told by a shopkeeper he could not buy milk because it was white. Babe Ruth barnstormed, as did Dizzy Dean, Josh Gibson, Bob Feller, Cool Papa Bell, and other future Hall of Famers, white and Black, with that wayfaring way of playing continuing into the early 1960s.

No player barnstormed as wide or far, for as long, as Paige. It suited his disposition: He was eager to follow the sun and money wherever they took him. Barnstorming let him live each day as it came, and days as a vagabond ballplayer offered boundless adventure and variety. He generated more offers than anyone, picking up as much as $500 for as few as three innings. Promoters knew he could fill the stands as well as mow down batters, so they booked him despite knowing he might not show. All of which makes feasible his fantastic claim to have pitched for as many as 250 teams over the course of his career.

His time on the road let him taste America at its least rehearsed. He sat on the porch and sang into the evening with a Black family that gave him a bed and meal in Dayton, Ohio, and ate ham and pumpkin pie with white ones in Iowa farm country. He thawed his hands over a fire next to the dugout in chilly Des Moines, rubbed his distended ankles after an all-night drive to Minnesota, and learned to spot a pool shark anywhere by the chalk in his breast pocket. In Harlem he relished the Renaissance. In New Orleans he savored the swing. He was what he called a travelin’ man, logging 30,000 miles a year and visiting “every state in the United States except Maine and Boston.” Among African-Americans, only the Pullman porter saw more of America. To Satchel, that freedom and movement were more delicious than the sweetest chocolate.

That does not mean barnstorming was easy. As rough as conditions were in the Negro Leagues, that looked like luxury next to Satchel’s early years on the road. He was away from home and family for months at a time. Driving all night and playing all day became his life. He learned to eat out of paper sacks and sleep three times a week. When he and his teammates could find and afford a hotel it might be five to a bed, and “sometimes the whole club’d be in one room.” He got to be an accomplished catnapper.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Bunny Downs, who drove the bus for a team Satchel barnstormed with, got a front-seat view of the strains and stresses: “Shucking corn, hoeing potatoes, picking cotton, ain’t no tougher than this business. No, sir. For a real, hard-working business, day in and day out, you gotta take this here whatchacallit, tourist baseball.”

A nationwide network of Negroes opened their homes to Satchel and other itinerant ballplayers. No need to post Vacancy signs; word spread quietly, much as it had for runaway slaves in the days of the Underground Railroad. As for food, “we had to go in the colored neighborhood if we wanted anything hot at all,” said Satchel. “If there was no colored in the town or no colored restaurant, then we went to the grocery store again for baloney sausage.”

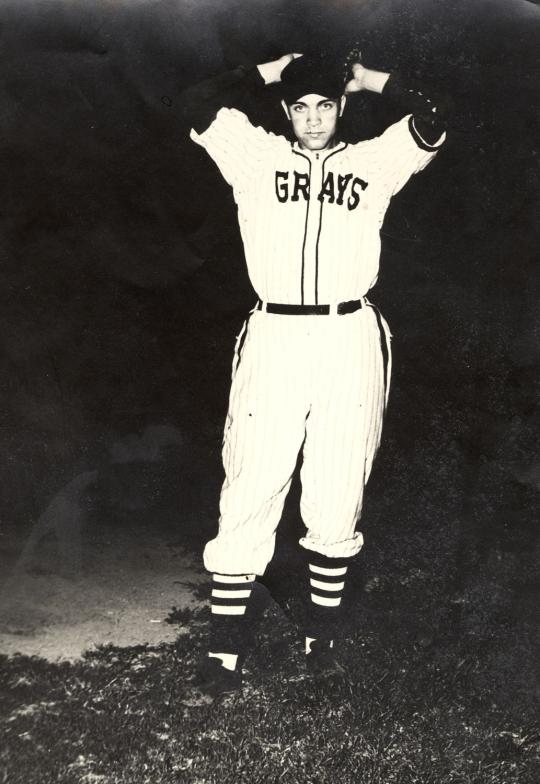

The more roadblocks they encountered, the more the gypsy ballplayers improvised. Having a lighter-skinned teammate like Wilmer Fields, the Homestead Grays pitcher, presented one such opportunity. Fields could order take-out or even rent a hotel room, with darker-hued teammates climbing through the window afterwards. Yet the ruse sometimes backfired, the way it did when Fields was in a whites-only café ordering sandwiches for a busload of Grays parked just out of sight. A chocolate-skinned teammate came in, intending to tease the pitcher. The restaurant owner was not amused, yelling at Fields, “Get the hell outta here.”

Spending so much time dueling with second-rate white teams and dodging the minefields of Jim Crow made Satchel and his teammates pros at using charm and humor to deflect tension. Batters hit one-handed or on their knees. Satchel took his warm-up throws sitting down, with his catcher stationed behind the plate in a rocking chair. Best of all was a riff called shadow ball. The hitter swung so hard, fielders reacted so convincingly, and the runner tore down the line so fast that fans could hardly tell that it was pantomime. It was baseball so brilliant it could be played without the ball.

Negro players knew it was best not to win by too many runs if they wanted to be invited back the next year. Oftentimes they did not record the score, which would have embarrassed the locals. They tried not to let racial animosities eat away at their humanity. Their stage might be shabby but their performance remained regal. In the early ‘30s Satchel was hired to pitch for a Black high school team in San Diego that was challenging its white rival. Partway through the contest he felt sorry enough for the white kids who were swinging without coming close that he let two of them get on base. Then he bore back down, striking out the San Diego players the way he always did when a game’s outcome was in doubt.

Did clowning and cutting corners undermine their dignity? That was a touchy subject for Negro ballplayers. While their tolerances varied on many topics, there was a consensus when it came to “Tomming:” It was taboo. Okay to put on a great display of baseball for white fans. Okay, too, to make them laugh between pitches or innings. But not to behave like that old slave in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who forever after symbolized subservience. So they calibrated their performances to ensure that the kidding never got in the way of their playing. They would do a lot to support their wives and kids, which was not easy for Negro men in that era, but never to the point of compromising their manhood. When opposing players got cocky, the Black barnstormers challenged them to a wager, then showed how dominating they could be with cash on the line. In rare cases where the crowd turned nasty, said Satchel’s Kansas City Monarchs teammate Connie Johnson, he and his teammates would “run twenty, twenty-five runs on ‘em, so they’d leave the park whispering.”

Ironically, it was the very integration of the sport that Connie Johnson and Satchel Paige had dreamed of and battled for that ended up killing not just the Negro Leagues, but much of the barnstorming that defined that era. Why pay to see Black players in pick-up games on makeshift fields when you could see them at Ebbets Field, Municipal Stadium, or on television? What was the appeal of watching Black and white teams face off on a cold fall afternoon when they were doing it every night throughout the long regular season. Lost, too, would be the story of the epic and tragic world of blackball and of all but its biggest legends.

Larry Tye, a former reporter at the Boston Globe, is the author of the Casey Award-winning biography, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend