- Home

- Our Stories

- Big star on the big screen

Big star on the big screen

Of all the famed athletes heralded during the “golden age of sports,” was there anyone who seemed more suited for a silver screen career than Babe Ruth with his larger-than-life persona and natural charisma?

The United States during the “Roaring Twenties” saw post-World War I economic prosperity and a cultural shift often associated with the “Jazz Age.” Ruth, the former southpaw pitching star turned left-handed slugger with the New York Yankees, personified these times, resulting in his opportunity to cash in on his fame and try his luck at an endeavor outside his comfort zone.

Ruth had ended 1926 season in a most unfortunate manner: In Game 7 of the World Series, the Yankees star was tagged out trying to steal second base with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning and trailing the Cardinals by a score of 3-2. But only days after his team fell in the Fall Classic, he spent two weeks barnstorming which was followed by a 12-week vaudeville tour for a reported $100,000, said to be the largest amount ever paid for a headliner.

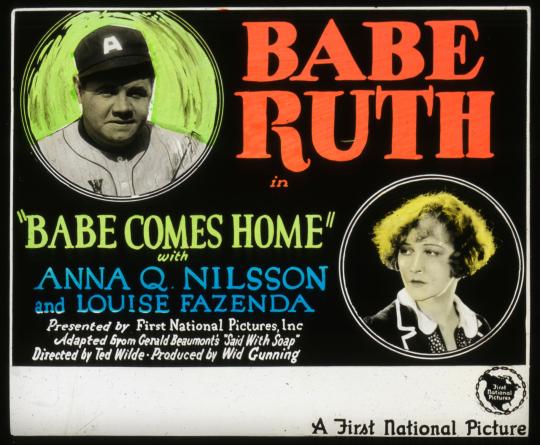

It was during Ruth’s West Coast leg of his vaudeville tour that it was announced on Jan. 22, 1927, that the Sultan of Swat would be trading in his bat and glove for a movie script and makeup. Newspapers across the country heralded the announcement, printing that Christy Walsh, the Bambino’s business representative, had stated his client had signed with First National Pictures, Inc., one of the leading studies of the day, to appear in the silent film, “Babe Comes Home,” based on a short story by Gerald Beaumont.

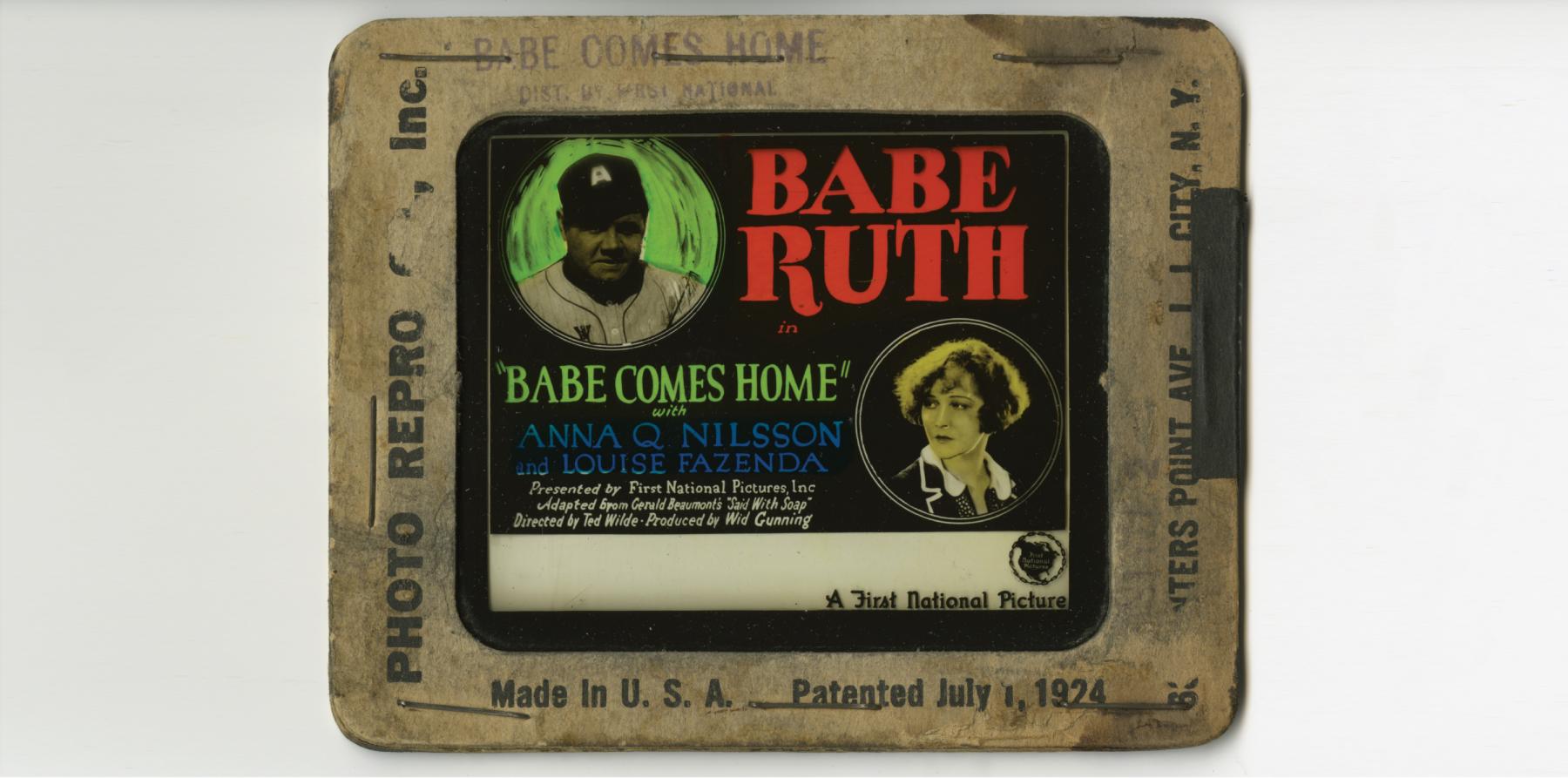

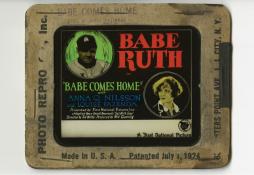

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s permanent collection includes a color "coming attraction" advertising lantern slide in cardboard mount, 4 inches wide and 3 ¼ inches high, for “Babe Comes Home.”

Ruth’s only other appearance acting in a movie up to this point came in 1920’s “Headin’ Home,” in which he starred as a fictionalized version of himself.

This was an era in Hollywood where a number famous athletes took star turns on the screen, including such familiar names as boxer Jack Dempsey, swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, automobile racer Barney Oldfield, football player Red Grange, golfer Bobby Jones, tennis player Bill Tilden and ice skater Sonja Henie.

Ted Wilde, the director of “Babe Comes Home,” also worked on many of legendary silent film comedian Harold Lloyd’s biggest hits, including 1928’s “Speedy,” which featured Ruth in an amusing role as a passenger in Lloyd’s taxi.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Ruth’s co-stars in the romantic comedy “Babe Comes Home” would be the beautiful and blonde Scandinavian Anna Q. Nilsson as the female lead and young comedienne Louise Fazenda in a supporting role.

As for the storyline in “Babe Comes Home,” Nilsson and Fazenda work in a laundry that washes the uniforms of the Angels baseball team, of which Babe Dugan, portrayed by Ruth, is the star. Nilsson’s character, Vernie, can’t understand why one particular uniform is so filthy, stained with dirt and tobacco juice, so she writes its owner a note about it. Dugan’s reply compels her to attend her first ballgame to see what he is like. As would have it in this genre, he hits a foul ball that gives her a black eye. Hoping to apologize, Dugan visits her home with candy and flowers and romance ensues.

Arguably the most important plot point comes when Vernie insists Dugan give up chewing tobacco, which precipitates a horrendous batting slump. Forced to chew gum instead, an unhappy Dugan continues to strike out in the big game … until Vernie hands him a plug of tobacco and he promptly socks a home run for the win.

According to John McCormick, general production manager on the West Coast for First National, “Babe Comes Home” was not written with Ruth in mind. The story was bought months earlier, he said, under the title “Said With Soap,” but when Ruth came to Los Angeles for his vaudeville turn, the production executives seized on the idea of having him play the lead.

Nilsson, the leading lady in “Babe Comes Home,” saw potential in the ballplayer, saying that she had played opposite all the great male actors of the screen and had never enjoyed any leading man so much as Ruth.

“What he lacks in polish and experience he makes up in ardor and seriousness,” she said. “The one thing Babe didn’t like was to be made up with rouge and mascara for the close-up scenes. I really believe that when he is more accustomed to this sort of thing he may develop into a screen Don Juan.”

For the three-week film shoot, which began in early February, reports had Ruth receiving anywhere from $50,000 to $100,000. He had made $52,000 as a player for the Yankees in 1926, a season in which the 31-year-old batted .372 while leading the American League with 47 home runs, 139 runs scored, and 153 RBI.

In order to stay in shape while involved in his motion picture work, Ruth had his personal trainer from New York, Artie McGovern, meet him in California. McGovern had been given credit by the King of Swat for his superb ’26 campaign.

In a letter that appeared in the Rye (N.Y.) Chronicle on Feb. 26, 1927, McGovern, a resident of Rye, outlined his training regimen for Ruth while the pair were on the West Coast.

“The Babe is going great guns and I don’t mean maybe. In fact, I think I will have to call a let up on the Babe’s training so that Arthur McGovern don’t go stale,” McGovern wrote. “After the road work, the Babe has a shower and a good massage and he starts his screen work around 8:30 a.m. and works steadily until 12 noon and I again get together with him for a one-hour session consisting of a little handball, medicine ball and the famous McGovern abdominal exercise.

“The Sultan of Swat has been very conscientious about his training work. In fact he is in a better psychological mood now than I have ever known him to be and has only revolted once toward the work and that was on Monday the 7th, the big fellow’s birthday (sic). He thought it was cruel that I should use my slave driving methods of pushing him out of bed at 6:30 on the day he felt he should celebrate.”

During a mid-February interview at Wrigley Field, the Los Angeles ballpark used for the movie’s baseball scenes, Ruth talked about giving up the sport that made him famous if his upcoming contract with the Yankees could not be resolved to his satisfaction.

“It would hurt me a lot to leave baseball. I’ve lived and breathed the game since I was a kid. After all, the financial aspect isn’t the big issue for I am making more out of this one picture than I did last season playing baseball,” Ruth said. “I’m not sure what I would do if I left the game. Yes, a baseball school for kids would be a great idea, I think. The sandlots are disappearing in the big cities and we need something to stimulate interest among the youth that have potential indications of being ballplayers.

“About the movies, I like the work. It gets rather tiresome at times, but if it was purely a financial question they make the best bid,” he added. “I would hate to leave baseball now. I have my greatest season coming and will be in wonderful shape when I reach training camp. I’m underweight now, around 226 pounds. I had hoped to reach training camp carrying about 230.”

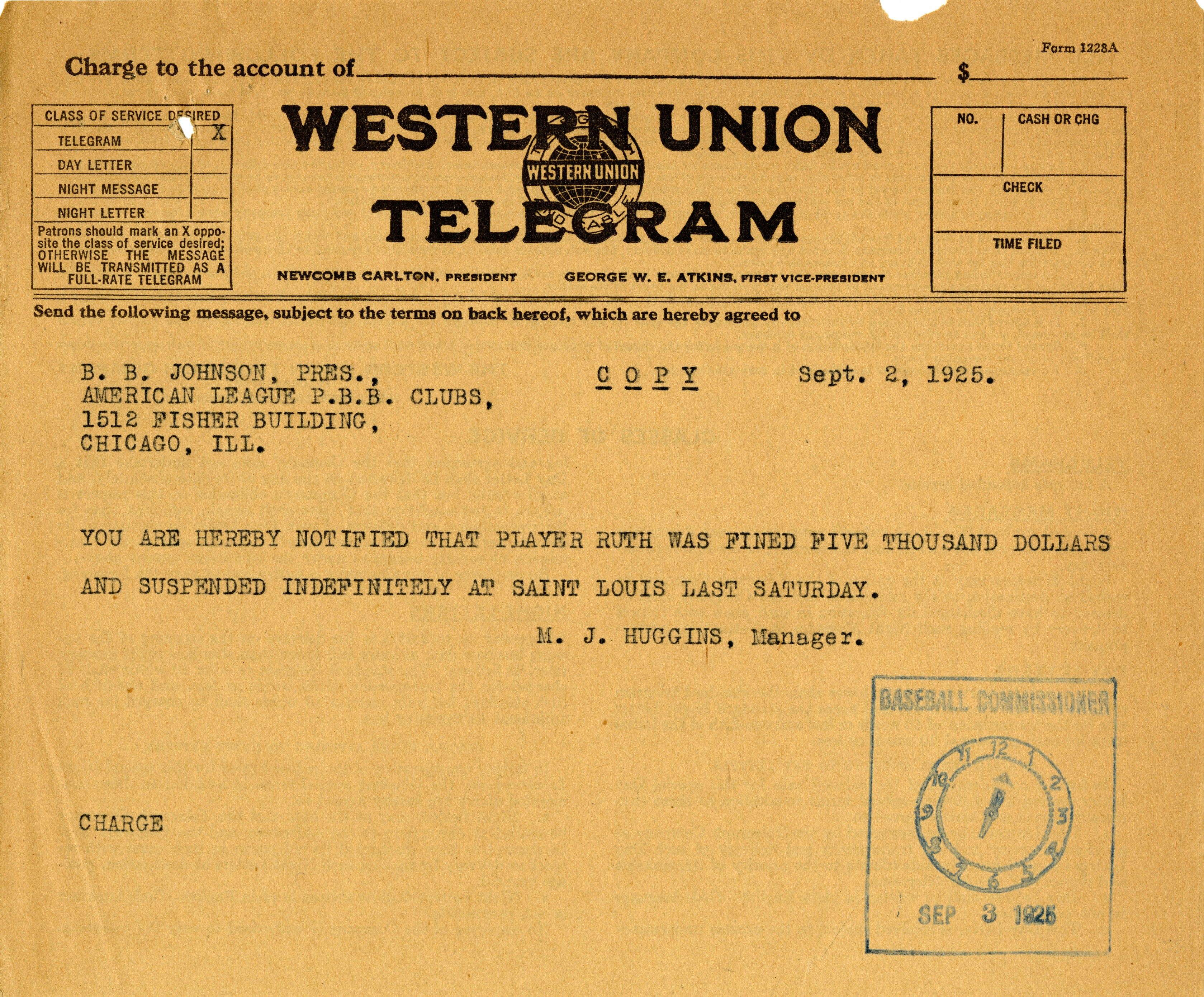

While in Hollywood, Ruth received in the mail a contract from the Yankees for the upcoming 1927 season offering him another $52,000. The slugger mailed the unsigned contract back with his demands of $100,000 a year for two years, plus $7,750 to pay his back fines.

“That is the identical sum I got last season and I have no intention of signing,” Ruth told reporters, adding he thought the offer was “exceeding poor judgement.”

But Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert soon explained, stating, “According to baseball laws, Ruth would have been a free agent if he didn’t get his new contract before February 15 and we sent him one just as a formality pending a conference with him.”

With the filming of “Babe Comes Home” complete, Ruth jumped on a train on Feb. 26 headed for New York City. Upon arriving at Grand Central Station on March 2, Ruth and Ruppert huddled the same day, and the result was a three-year deal for $70,000 a year that made home-run king the highest paid player in the game.

With the 1927 season in its earlier weeks, Ruth told reporters he was looking forward to acting in front of the motion picture cameras again at the conclusion of the present baseball season.

“I like the movies much better than I expected,” Ruth declared. “It was great fun and I thoroughly enjoyed making some of the scenes in ‘Babe Comes Homes’ – especially one scene which they made me shoot over about a dozen times. In it I had to crawl under a bed, chasing a rat, and when I came out I had a mouse trap on my finger. I think they made me do it on purpose because of my 220 pounds.”

When “Babe Comes Home” was released in May 1927, up against other baseball pictures like “Slide, Kelly, Slide” and “Casey at the Bat,” it was not a financial success but Ruth and the film did garner some favorable reviews.

The Film Daily wrote, “Babe Ruth’s name will undoubtedly sell the picture and there are enough laughs not to disappoint the fans who may come in expecting to find their baseball idol performing after the order of Charlie Chaplin. Babe isn’t a comedian but he has been surrounded with a good cast and provided with enough good opportunities to permit him to get by with it very nicely.”

According to Motion Picture News, “’Babe Comes Home’ is an amusing comedy which tells its little story crisply enough, like the way its star smacks the ol’ apple. Through skillful direction and an ability to adapt himself to the situations, whether serious or humorous, the Babe registers all the necessary emotions. Don’t take it from us that he is liable to cause Chaplin, Lloyd, et al., to do a fadeout. Yet, if he wanted to quit the diamond and crash the movies for keeps he would more than make good.”

The opinion expressed by Photoplay was similar, calling Ruth “a tremendous figure whether he hits a home run magnificently or strikes out magnificently. This same good humored, never-quite-grown-up personality radiates out of ‘Babe Comes Home.’ The lad is a screen bet. And he can act. Don’t let anyone tell you different. Without effort, he is humorous and he is touching.”

Ruth was also a fan, saying in 1928, “I’ve seen my picture about 15 times and always go again if it is appearing in the town we’re playing ball in.”

Unfortunately, not all reviews were as positive, with one particular woman in a Chicago suburb announcing that “Babe Ruth cannot spit tobacco juice on the screens of Highland Park theatres and get away with it,” refusing to allow “Babe Comes Home” to be shown in her parish.

Later in 1927, “The Jazz Singer,” featuring Al Jolson, staked claim to the first talking movie. Within a few years the silent film era was only a memory.

Today, “Babe Comes Home” is a “lost” film, meaning no copies are known to exist, either intentionally destroyed, with the thinking they had no value, or chemically destroyed because of the nitrate film used.

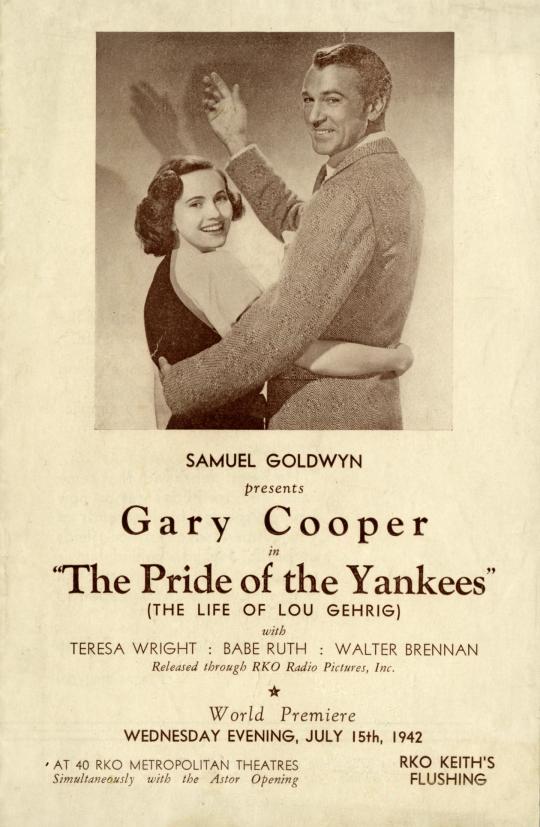

And though Ruth never had the film career many expected, his last role was playing himself in the 1942 Lou Gehrig biopic “The Pride of the Yankees,” he did leave an impression.

“The Babe had no more expression than a wooden Indian,” someone once said. “Yet Ruth lasted through three pictures or, if you prefer, was given three rich strikes by Hollywood.”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum