- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Larry Haney

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

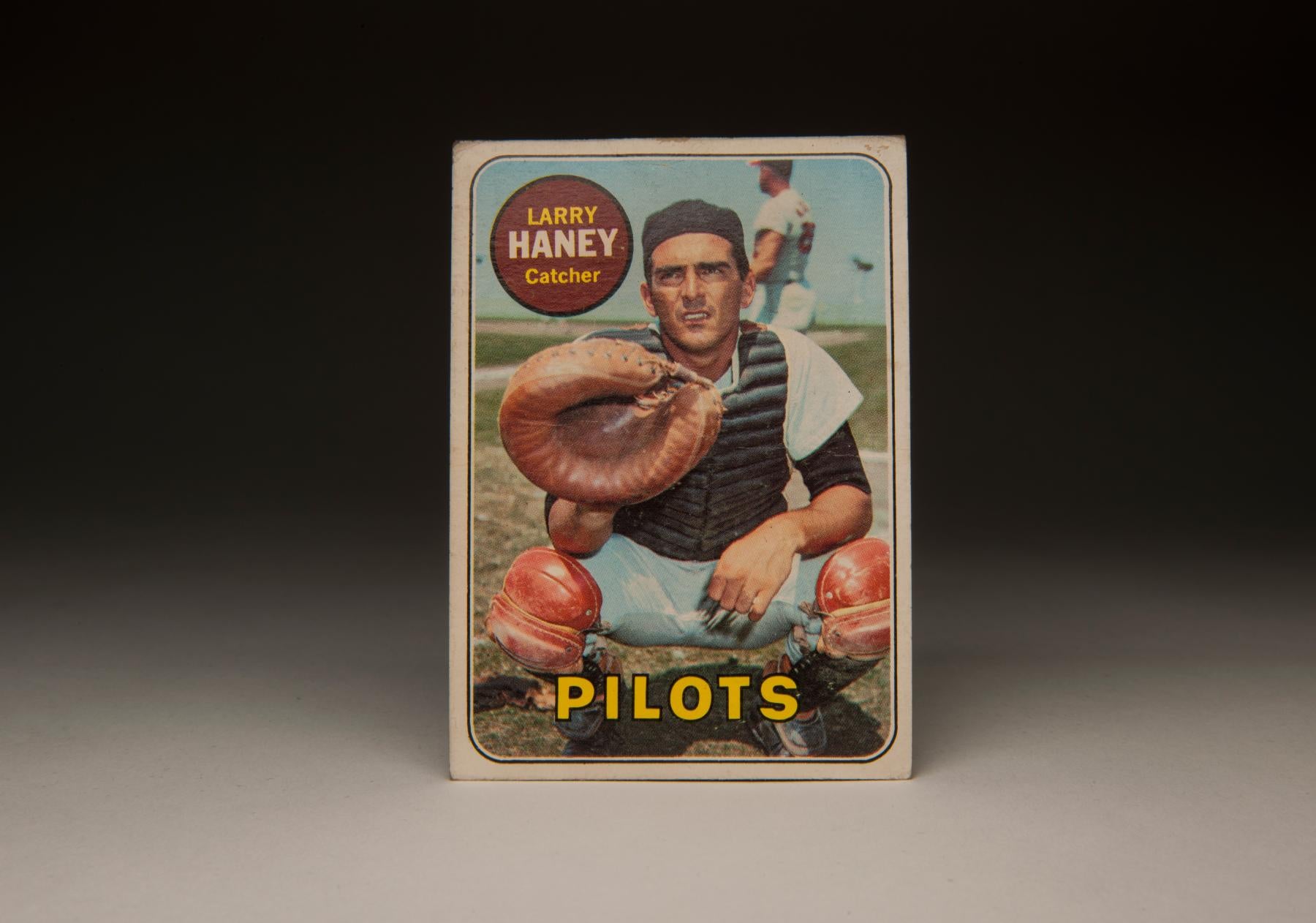

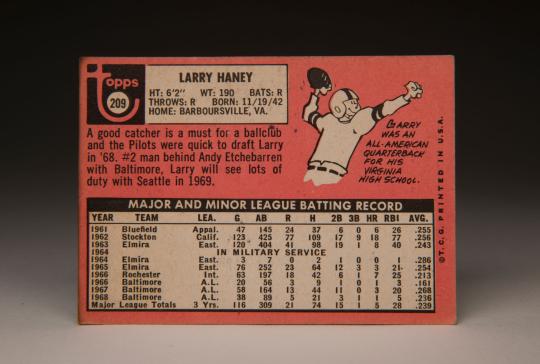

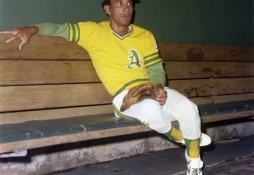

It doesn’t take long to realize that something is amiss with Larry Haney’s 1969 Topps card. After all, there hasn’t been a left-handed throwing catcher since Benny Distefano (in 1989) and Mike Squires (in 1980), two players from the decade of the 1980s. Lefty throwing catchers are a rare commodity in baseball history - so rare that there have only been 30 in the history of the major leagues - even though the reasons behind their scarcity remain something of a debated mystery.

Contrary to appearances, Larry Haney was not a left-handed throwing catcher. It only looks that way on his Topps card, which clearly has his catcher’s mitt on his right hand. There have been other players who have been shown posing with the “wrong” hand, and they have achieved more fame than Haney. Hank Aaron became the subject of much curiosity when Topps showed the eventual home run king in a left-handed batting pose on his 1957 card. And then in 1989, Upper Deck issued its card of Dale Murphy showing him with his bat on his left shoulder, instead of his right. As with Aaron, the card mistake was simply the product of a photo negative being accidentally reversed.

Haney’s card did not receive quite as much attention as the Aaron and Murphy errors, in large part because of his status as a good-field, no-hit backup catcher. When you’re a second-string receiver, it’s hard to sustain much fame, even in the business of baseball cards.

So how exactly did this Haney card come about? For years, there was a theory espoused by some collectors who thought that Haney was trying to gain attention for himself by intentionally wearing a left-handed catcher’s mitt and pretending to play the position with the wrong hand. In a world where conspiracy theories seem to take on added life, the story sounded plausible to me - as gullible as I am.

It does make for a good story, but it’s not true. A conversation with the former president of Topps, the late Sy Berger, reveals the real reason behind the mistake. Back in 2002, Berger came to Cooperstown for an event celebrating the 50th anniversary of Topps baseball cards. During our conversation, I asked him about the Haney card and how it came to be in its unusual form. Sy gave me the scoop. Topps simply made a mistake in its photo processing, reversing the negative as it had once done with the Aaron card; Mr. Haney himself had nothing to do with the error. In fact, the 1969 card features the same photo that was used by Topps in the 1968 set, most likely because players had refused to sit for new photographs because of their dissatisfaction with Topps’ level of compensation. So Topps used the image from the previous year, when it had the image going in the right direction.

It’s also worth noting that this outdated photograph, which was almost certainly taken during Spring Training in 1967, has Haney wearing the uniform of the Baltimore Orioles. (The Orioles’ colors are perhaps more evident in the background figure, who could be Boog Powell, or might be one of Baltimore’s coaches.) The Seattle Pilots, Haney’s actual team in 1969, were not yet in existence in 1967.

Now that we’ve cleared up some of the mysteries of the card, let’s learn more about the subject. In many ways, Haney was the Jose Molina of his era. A lifetime .215 hitter with no power, Haney excelled at the defensive side of the game. He was a catching artist, to put it mildly. He had soft hands, blocked pitches well, and called a good game for his pitchers. He could throw, too. For his career, he threw out 39 percent of opposing basestealers. He also gunned down eight baserunners on pickoff plays. The Oakland A’s thought so much of Haney’s catching skills that they acquired him three different times, including twice during their world championship run in the early 1970s.

Originally signed to a $50,000 bonus by the Baltimore Orioles in 1961, Haney would make his major league debut in 1966. His first game was notable: He clubbed a home run, taking John O’Donoghue of the Cleveland Indians deep in his second big league at-bat. For the most part, Haney played sparingly in three seasons for the Birds while serving as a backup to starting catcher Andy Etchebarren. While he didn’t play much in Baltimore, the time there turned out to be worthwhile. In 1966, he picked up a World Series ring as the Orioles swept the Los Angeles Dodgers to win the championship.

Haney remained a backup in 1967 and ’68. His lack of playing time became a running joke in the latter season. By mid-July, he had played in all of seven innings. “I might get in a complete game before the season’s out,” a tongue-in-cheek Haney told Doug Brown of the Sporting News. With Etchebarren and Elrod Hendricks ahead of him on the depth chart, the Orioles unsurprisingly left Haney unprotected in the expansion draft. Finally, in the 32nd round of the draft, the Seattle Pilots selected Haney.

Unfortunately for Haney, the Pilots had catching depth, too. With Jerry McNertney and veteran Jim Pagliaroni also around, the Pilots relegated Haney to third-string status. He appeared in only 22 games for Seattle, but did gain some notoriety for the wrong reason. In a May 31st game against the Detroit Tigers, Haney set a Pilots record by committing two errors in one game. That kind of performance was not typical of a defensive stalwart like Haney and probably played little influence in Seattle’s decision to trade him, but the Pilots soon decided to part ways with Haney. On June 14, 1969, the Pilots shipped the veteran receiver to the A’s for second baseman John Donaldson.

Haney’s play suffered in Oakland because of two injuries, a banged-up thumb and a broken toe. As a result of the falloff, he spent much of the next three seasons toiling in the minor leagues, interspersed by only brief cups of coffee in Oakland.

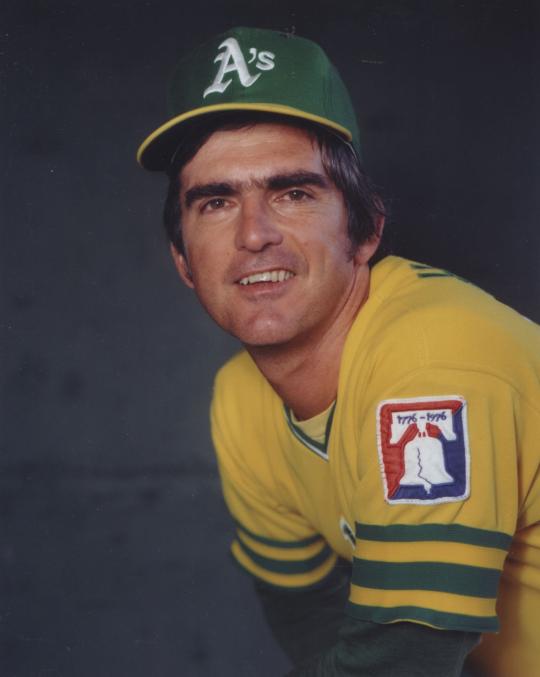

In May of 1972, the A’s sold Haney to the San Diego Padres’ organization, but he never actually donned those lovely brown and yellow uniforms favored by the Pods back in the day. So in September, he came back to the A’s, spent a brief time with the St. Louis Cardinals, and then returned to the A’s yet again. During his third and final stint with Oakland, Haney appeared in two games during the 1974 World Series and earned the second world championship ring of his career.

Haney then became involved in another card error, albeit of a different kind. His 1975 Topps card displays an in-action photograph of an Oakland catcher awaiting a throw at home plate, but it’s not Haney in the picture. It’s actually former A’s catcher Dave Duncan, who had not played for the A’s since 1972, having long since been traded away to the Cleveland Indians.

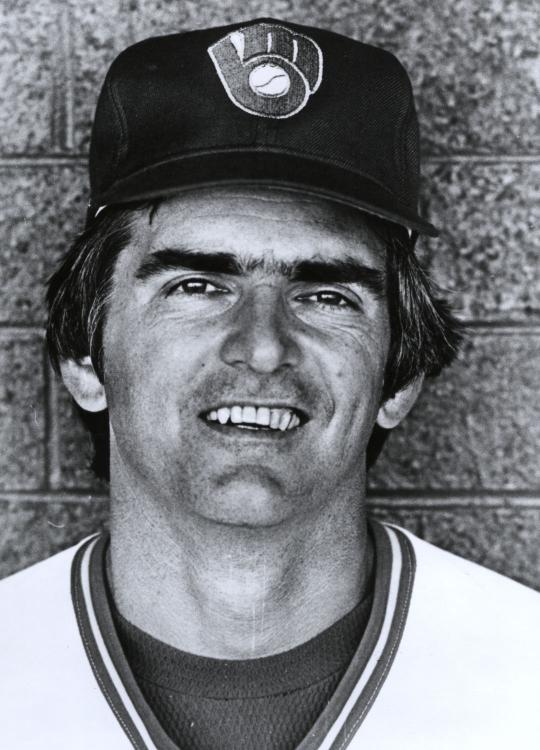

After the 1976 season, the A’s sold Haney’s contract to the Milwaukee Brewers, where he was reunited with former Orioles teammate Andy Etchebarren, who had entered pro ball with him back in 1961. When the Brewers finally released Haney in 1978, ending his playing career, they offered him a job as a bullpen coach, and then later as pitching coach. It was during his tenure as pitching coach that I remember a slightly amusing episode involving Haney. During one game against the Chicago White Sox, Haney was walking slowly to the mound to talk to his pitcher. One of the Sox broadcasters - I believe it was Tom Paciorek - noticed Haney’s deliberate gait and made reference to the slow-moving con man character on the old Green Acres television show. “Look, it’s Mr. Haney. Here comes Mr. Haney.” I’m not sure what Larry thought about the comparison, but for a fan of Green Acres like myself, it was a fond reference.

After a few years, Haney moved into a scouting position with the Brewers, remaining there until his retirement from the game in 2007. He also forged something of a family legacy within the game; Haney’s son, Chris, pitched 11 seasons in the major leagues, while Larry’s cousin, Mike Cubbage, was a big league infielder from 1974 to 1981.

All in all, that’s a pretty substantial contribution for a player who spent much of the sixties and seventies as a backup catcher. Just from the perspective of baseball cards, Haney happened to become part of two of the more notable error cards ever produced. If for no other reason than that, avid collectors of cards will never forget Mr. Haney.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame