- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Veale

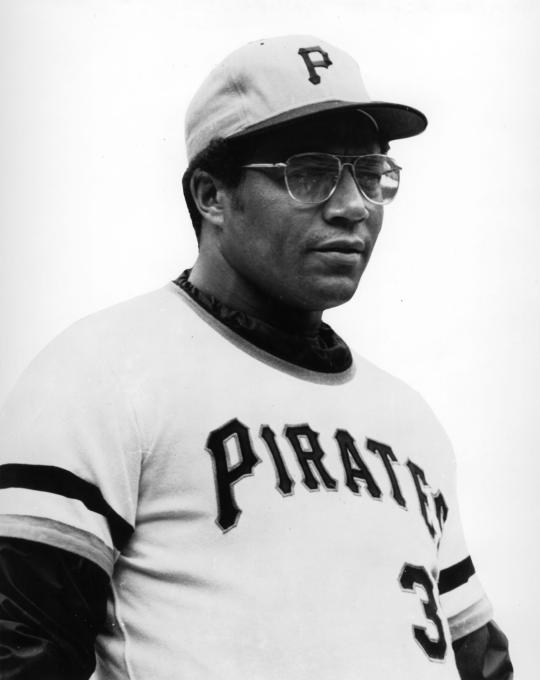

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Bob Veale

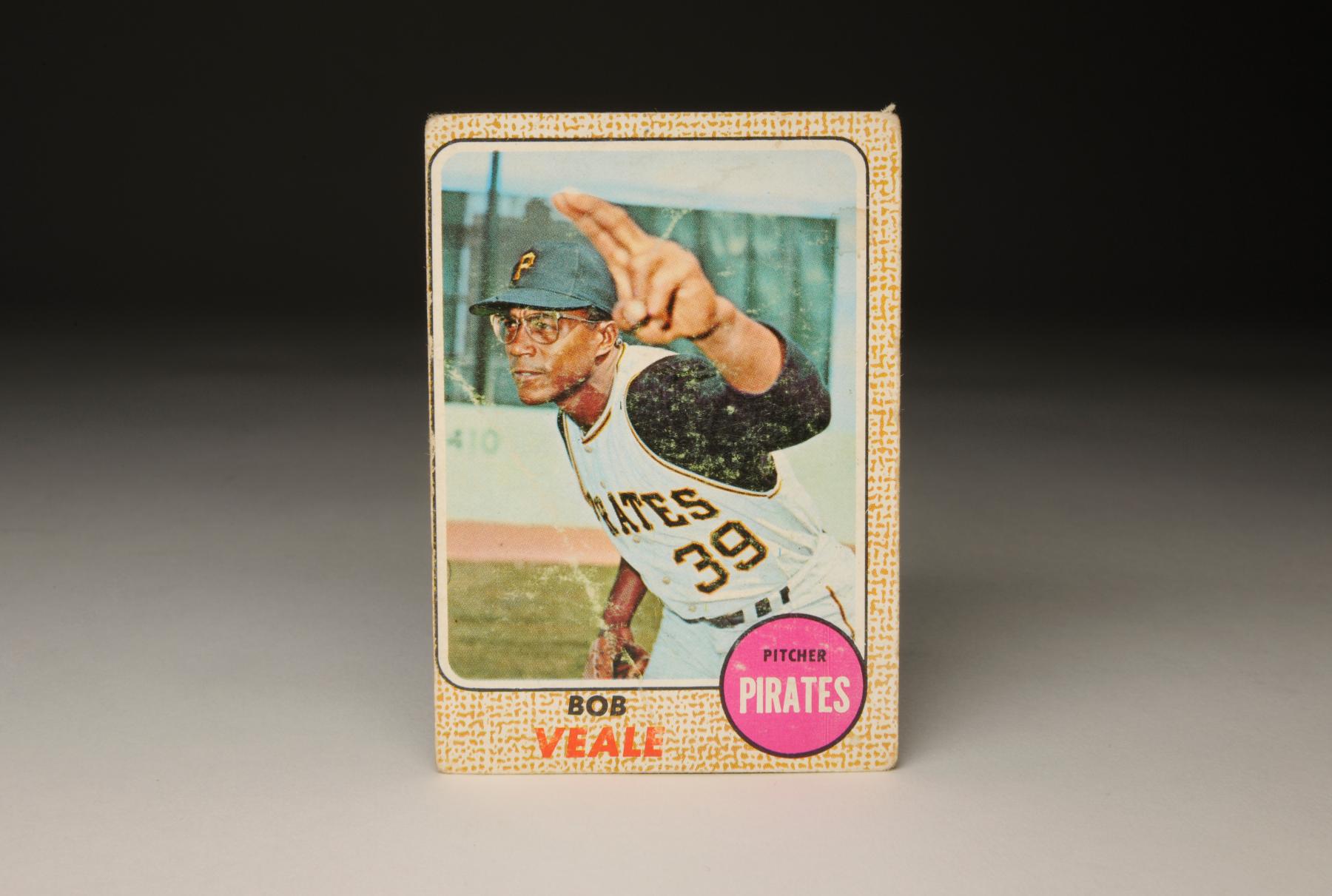

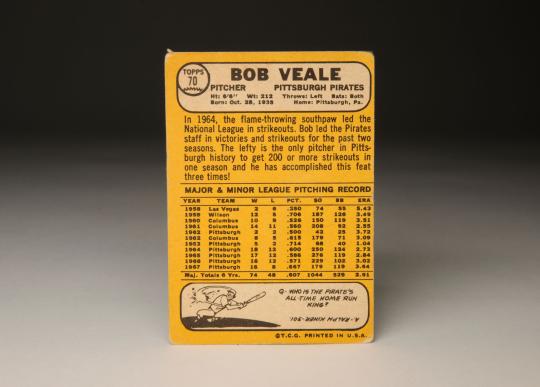

The 1968 Topps set has never received its full due. Ever since I first saw these cards, I have appreciated the speckled borders, which are so different from all of the other sets that Topps has produced. The black borders of 1971, the multicolored borders of 1975... they tend to be remembered with fondness, but the speckled look gives the cards a three-dimensional quality. In addition, the photography in the ‘68 set is solid, the cardboard is thick, and even the backs of the cards are nifty, with a combination of yellow and white that make the statistics and the biographies stand out in terms of aesthetics and readability.

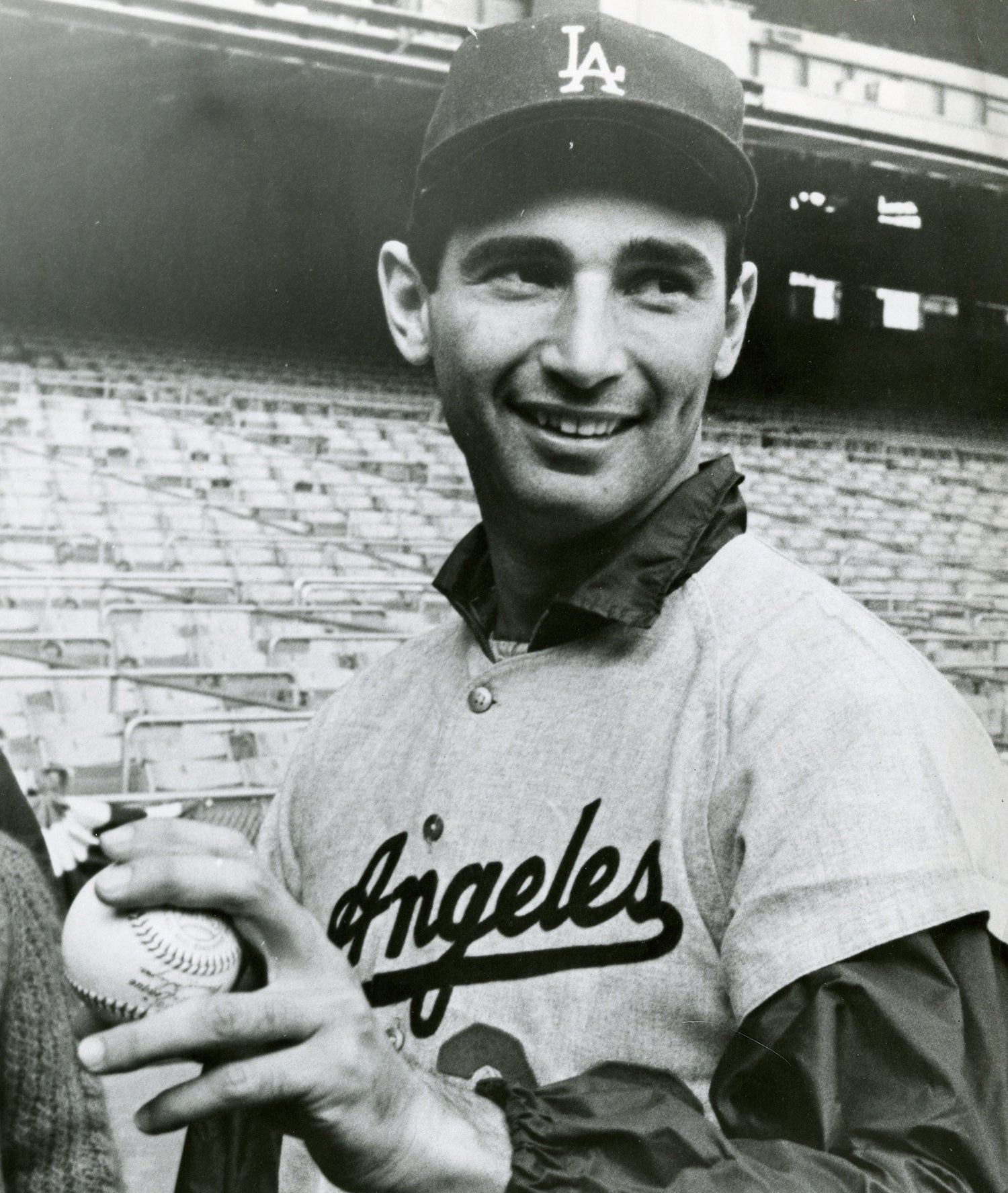

Within the ’68 set, the card of Bob Veale remains one of my favorites. Set against the backdrop of a Spring Training stadium, the card gives us a good look at those classic sleeveless uniforms worn by the Pittsburgh Pirates of that era. The combination of black and gold, coupled with the old-fashioned vest look, made the Pirates look like serious ballplayers. I loved those uniforms.

Topps had not yet introduced action shots in its presentation of players, but the Veale card at least gives us the illusion of action. Yes, he is doing nothing more than feigning his pitching delivery, but at least he’s doing it full-heartedly, with a grimace on his face, his arm up high, and with the added bonus of a pitching grip. With his index and middle fingers pressed together and fully extended - they’re practically in the cameraman’s face - Veale is giving us an up-close look at his curveball grip. The curve wasn’t Veale’s best pitch, but it became a key weapon as his career progressed, an important part of a diverse five-pitch repertoire.

When members of the media ask great hitters from the 1960s to name the left-handed pitchers they most feared facing, Veale’s name usually comes up in the conversation. How intimidating was Veale? Here’s one way to think about it. In his early years, Veale’s fastball drew comparisons to that of Sandy Koufax and Sam McDowell, who were generally regarded as the hardest throwing pitchers of the mid-1960s. Koufax is a Hall of Famer; Sudden Sam, as McDowell was known, might have been, if not for problems with alcohol and persistent pain in his back and neck. When sportswriters - not to mention opposing hitters - are putting another pitcher in the same class as Koufax, for any reason, that is an indication of something memorable.

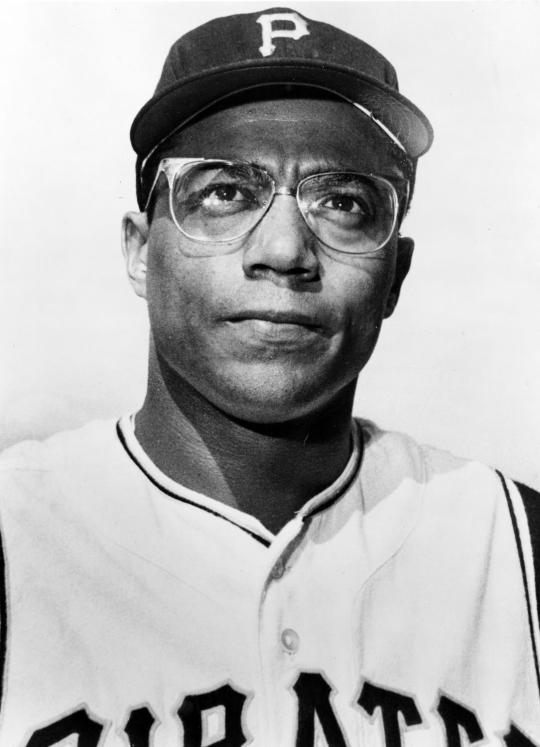

Additionally, Veale was a physical specimen of enormous proportions. He stood 6-foot-6 and weighed 220 pounds, making him look more like he should have been linebacker for the Pittsburgh Steelers than pitching in the 1960s. Not only was he physically larger than most pitchers of his era, he was also bigger than most hitters in his day. Given his sheer size, if a batter didn’t like an inside fastball from Veale, he wasn’t likely to charge the mound or offer even a verbal challenge to the hulking left-hander.

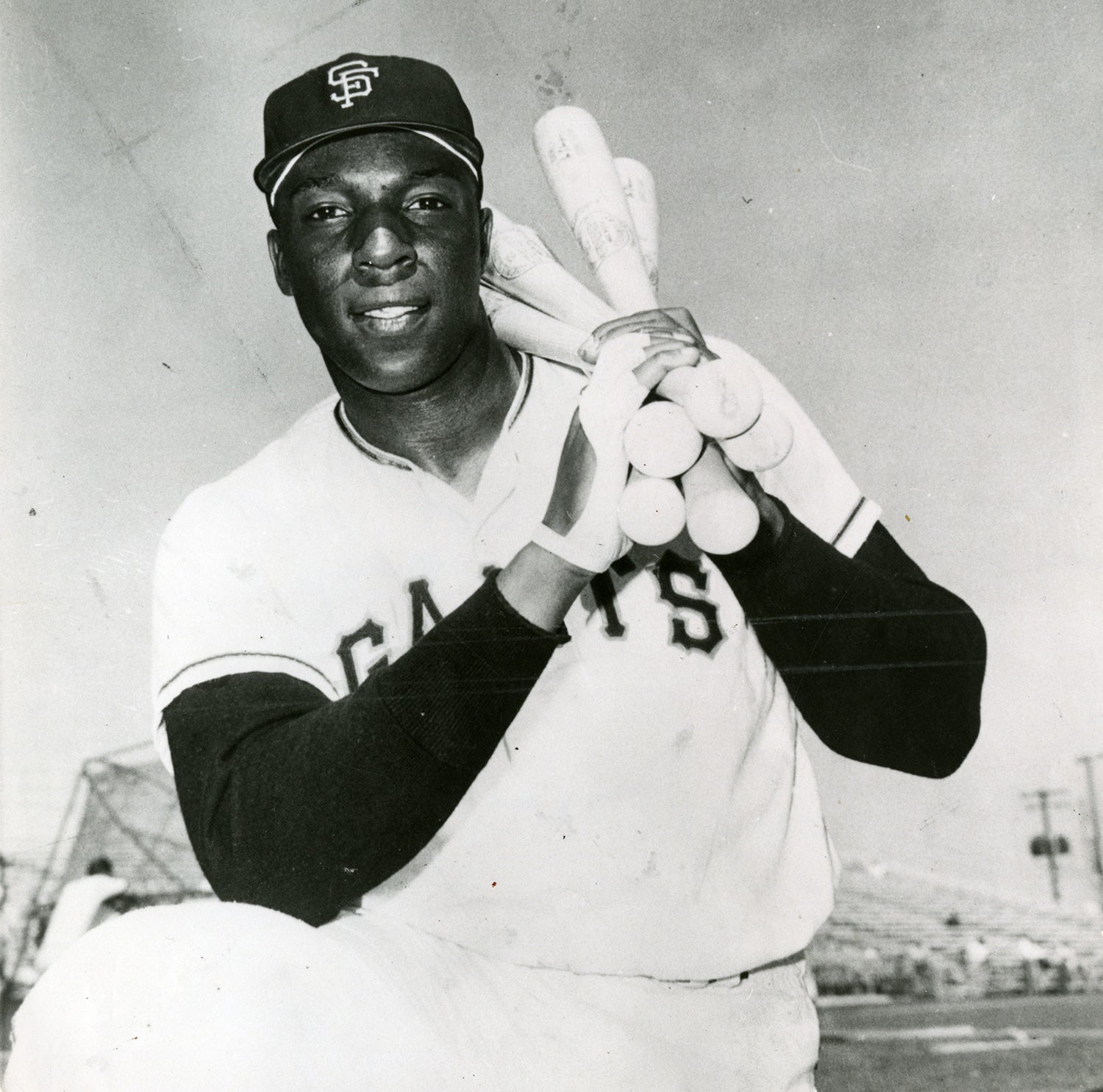

Just for fun, Veale had a bit of Ryne Duren in him. Much like the hard-throwing right-handed reliever who once starred for the New York Yankees, Veale wore glasses. Sometimes Veale squinted, giving the hitter reason to worry whether Veale could actually see them. Some hitters, great ones like Lou Brock and Willie McCovey, have claimed that Veale actually removed his glasses during some of his starts, just to further the notion that he didn’t know exactly where the ball was going. In truth, Veale’s ability to intimidate was underscored by his actual wildness. After all, he led the National League in walks on four occasions. Three of those times, he exceeded 100 walks.

Other statistics support the image Veale as something of a monster on the mound. In 1964, he struck out 250 batters, leading everyone in the National League, including the great Koufax. The following year, Veale increased his total to 276. Though radar gun readings were not commonly used in the 1960s, it’s a safe bet that Veale, at his peak, threw his fastball in the range of 96 to 100 miles per hour. Keep in mind that much of this was occurring during the dead ball era of the 1960s, when pitchers’ mounds stood at 15 inches above the rest of the playing field.

By 1968, the year of this Topps card, Veale’s reputation had reached full force. In the Year of the Pitcher, he posted an ERA of 2.05, the lowest of any of his full seasons as a starter. In logging 245 innings - a remarkable total given that he pitched with elbow pain much of the season - he allowed only 187 hits, completed 13 games, and spun four shutouts. Only a lack of run support prevented him from a winning record. With the Pirates struggling to score in a season starved for runs, Veale settled for a record of 13-14.

In 1969, Veale would post another 200-strikeout season, the final time that he reached the milestone. That was his last indication of dominance. In 1970, his strikeout total fell below 180, while his ERA rose to nearly 4.00. Now 33 years old, Veale was showing the inevitable signs of decline.

By 1971, the onset of age and the development of back problems took away a significant portion of Veale’s fastball and forced the Pirates to switch him from starter to reliever. Some observers of the team wondered if Veale, with his streaks of wildness, would be suited to pitching out of the bullpen. Others questioned how his arm would respond to pitching three to four times a week. And then there was the issue of his physical conditioning. Veale made the mistake of reporting to Spring Training at slightly more than 240 pounds, the heaviest mark of his career. At a time when newspapers lacked political correctness, the Pittsburgh Press newspaper featured the following blunt headline: “Pirate Fat Man Battles Weight.”

Veale shook off the insults, along with the trade rumors that had him headed to the Detroit Tigers (for veteran shortstop Eddie Brinkman). He worked diligently that spring in removing the excess weight, lowering his poundage to 230, and claimed a spot on the Pirates’ Opening Day roster.

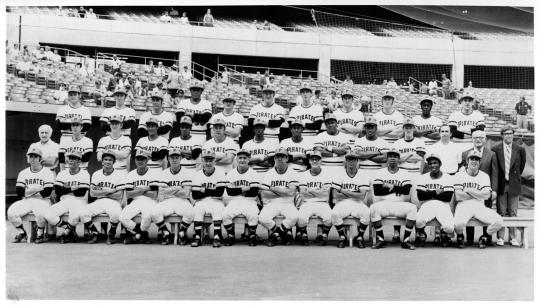

The 1971 season provided Veale with an opportunity to take part in an unusual episode of baseball history. On September 1, the Pirates became the first major league team to field an all-black lineup. That lineup, which included stars like Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and Al Oliver, helped the Pirates to a blowout victory over the Philadelphia Phillies. Veale pitched out of the bullpen that day, one of three Pirates relievers to take his turn in place of an ineffective Dock Ellis.

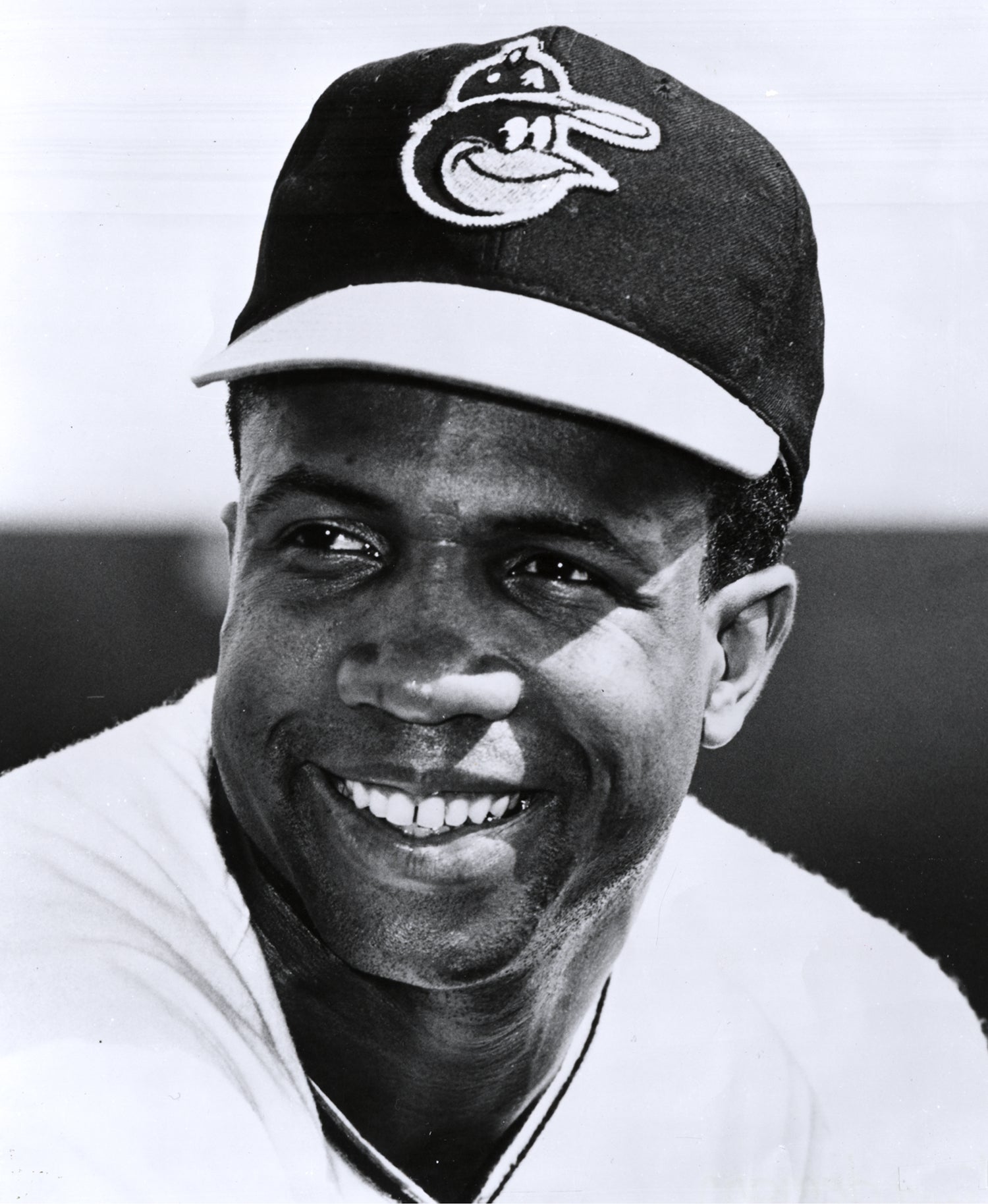

Veale remained in Pittsburgh for the entire season, pitching primarily in long and mop-up relief. That fall, he earned his first and only visit to the postseason. After winning the National League East, Veale’s Pirates faced the San Francisco Giants in the NLCS and the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Veale made only one ineffective appearance in the postseason, but that hardly mattered, as he and the Pirates earned World Championship rings for upsetting an Orioles team filled with Hall of Fame talent.

For the 1971 season, Veale posted an ERA of 6.69, the worst of his career. A few bad outings inflated that number, but it was obvious that Veale had passed his prime. After the season, several Pittsburgh writers speculated that Veale might draw his unconditional release.

It didn’t happen. The Pirates retained Veale, hoping that he would fare better after a season of adjustment to the bullpen. His spot secured, Topps printed a 1972 card for Veale. The high-numbered card, No. 729 to be exact, did not come out until later in the season. By the time the card hit stationery stores, Veale’s Pirate career had come to an end. In his first five outings of the new season, he had given up seven walks and 10 hits over nine innings. Reluctantly, the Pirates placed Veale, who was popular in the Pittsburgh clubhouse, on waivers. When no other major league team claimed him, Veale accepted an assignment to the Bucs’ minor league affiliate, the wonderfully named Charleston Charlies.

Veale remained in the minor leagues until September 2. Opting not to bring Veale up for the stretch run as they made another push for a division title, the Pirates instead sold him to the Boston Red Sox, who were contending for a title of their own in the American League East.

Joining a league where hitters had little familiarity with him, Veale pitched extremely well in six games for the Red Sox, hurling eight scoreless innings of relief, while picking up two wins and two saves. Unfortunately, Veale’s pitching wasn’t enough to help the Red Sox overtake the Detroit Tigers in the pennant race, but his impressive showing convinced the front office to bring him back for another go-round.

Veale pitched well again in 1973, but a sudden falloff in 1974, prompted in part by a series of injuries, led him to retirement. Veale was done with pitching, but not with baseball. He wanted to coach, even though very few black men held coaching positions at the time. Frank Robinson had just been named manager of the Cleveland Indians, but that didn’t meant that other teams were open to the idea of an African-American skipper, or even a black coach.

After sitting out the 1975 season, Veale found work with the Atlanta Braves, who made him one of their minor league pitching instructors. He later joined the Yankees, working in a similar capacity for several seasons.

In 1983, the 49-year-old Veale landed in Utica, N.Y., the hometown of his former Pirates teammate, Dave Cash. The Utica Blue Sox, an independent minor league team owned by sportswriter Roger Kahn, brought Veale on as their pitching coach. Stocked with minor league veterans and aging renegades who were good minor league players but were considered non-prospects, the Blue Sox shocked the minor league world by winning the New York-Penn League championship that summer.

I started working in Utica in 1987, missing Veale by just four years. Even though he is long since retired from coaching, baseball diehards in Utica still remember him for being quotable and outgoing. Recalled for having a comedian’s sense of humor and a baseball savant’s knowledge, he was well-liked by everybody within the Blue Sox’ organization. On a team where the front office and coaching staff often seemed to be at odds, Veale remained above the fray - calm and even keeled.

Veale, who passed away in January 2025 at the age of 89, was never the “monster” that his size and fastball made him out to be. As former Pirates outfielder Gene Clines, who played with Veale from 1970 to 1972, once told author Donald Hall, “[Bob] can throw the ball through a brick wall, but everybody knew that he was a gentle giant.

“If Veale would knock you down, it had to be a mistake. He didn’t want to hurt anybody.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum