- Home

- Our Stories

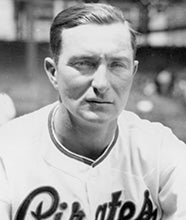

- Little Lloyd Waner swung a big bat

Little Lloyd Waner swung a big bat

He played in the shadow of his big brother all his life – a brother who would go on to record more than 3,000 big league hits.

But Lloyd Waner carved out his own legend on the diamond. And 110 years ago this week, Lloyd Waner began his journey.

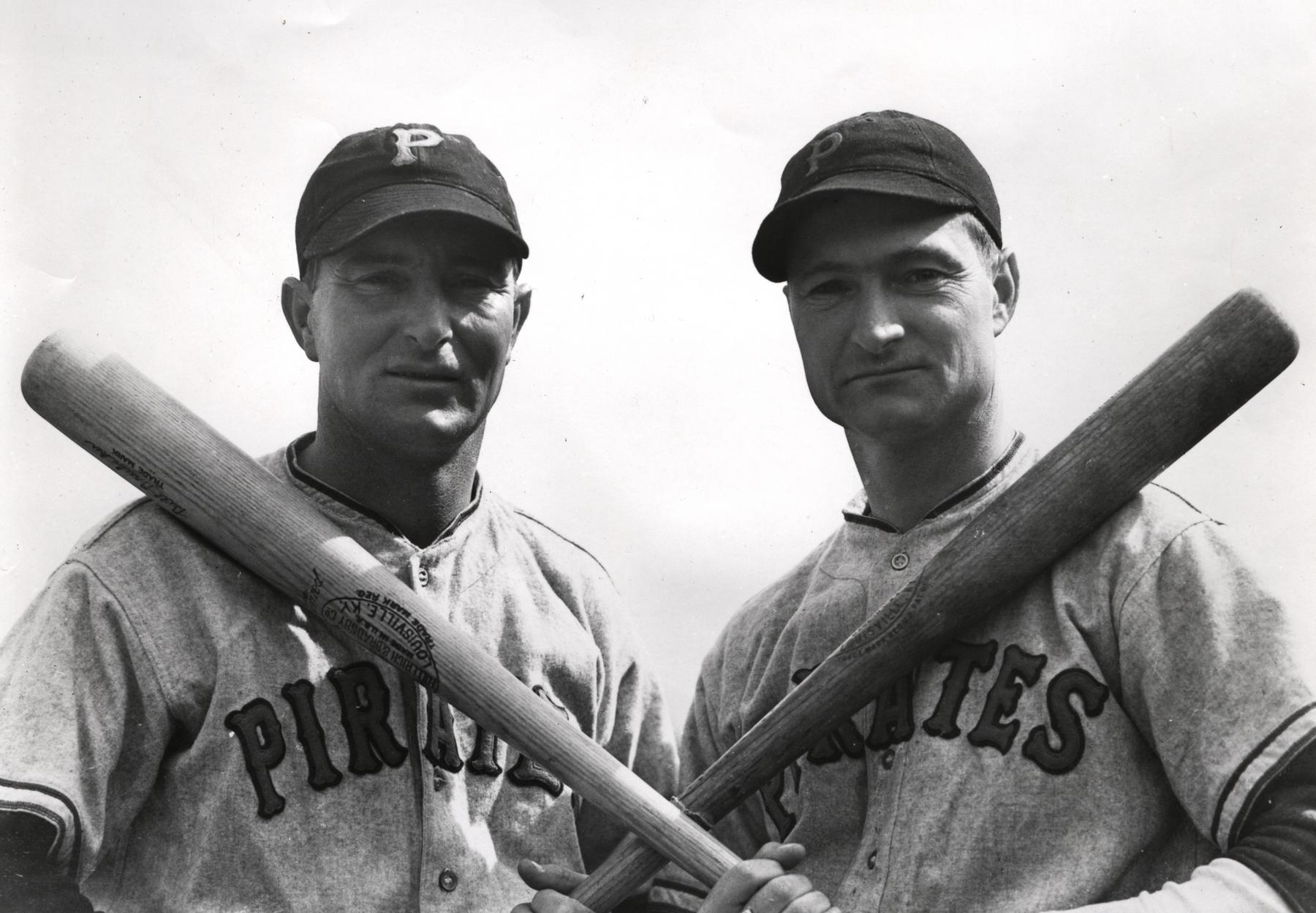

Lloyd, the younger of the famous Hall of Fame Waner brothers, was born March 16, 1906, in Harrah, Okla. More often than not, Lloyd played second fiddle as “Little Poison” to his big brother Paul Waner’s “Big Poison,” after a sports writer misheard a Brooklyn fan’s accent pronouncing here comes that “little person.”

The Waner brothers may have been small in stature – at 5-foot-9, Lloyd actually stood an inch taller than Paul – but they weren’t lacking in skills even outside of baseball. In fact, the brothers capitalized on their fame by forming a vaudeville act in which Lloyd played violin while his brother played the saxophone. Although they may have made good money during these acts, their true fame and calling came from baseball.

“We got $2,100 a week (in vaudeville), which was really big money in those days,” Lloyd once recalled. “The most I ever made in a (baseball) season was $13,500.”

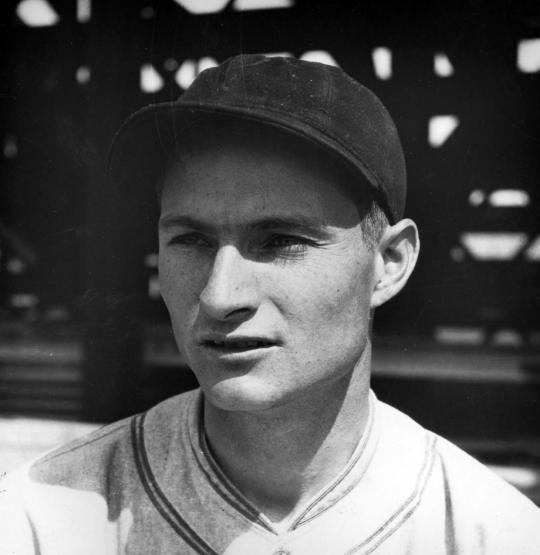

Lloyd had an amazing rookie season, batting .355, leading the league with 133 runs scored and setting a rookie NL record of 223 hits in 1927. He helped the Pittsburgh Pirates win the NL pennant before losing the World Series to the Yankees.

“We went back home to Oklahoma,” Paul said, “and darned if they didn’t have a parade for us. Lloyd and I outhit Ruth and Gehrig, .367 to .357, so everybody was happy.”

The Waner brothers went on the vaudeville tour following the memorable year. Paul would come on stage first and ask an out of breath Lloyd, “Where were you?” Lloyd then would reply by saying he just finished chasing down the last ball Babe Ruth hit.

It was written that Pittsburgh actually lost the ’27 Series the day before it started by sitting in Forbes Field stands and watching the Yankees crush ball after ball over the fence. However in an interview in 1967, when Lloyd was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans’ Committee, Lloyd laid that theory to rest.

“Only one game wasn’t close and I think that score was 8-1. We gave them a battle. Of course, those Yanks of ’27 were the greatest ball team I ever saw. They had everything.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Lloyd and Paul, however, kept the Pirates competitive for years with a sibling rivalry that fueled their performance.

“I’ll never forget one day in Cincinnati,” said Lloyd. “The old park there had a low fence in front of the box seats down behind third base. I swung at a pitch and sliced it about a foot inside the foul line and it went into the seats on one bounce. In those days it was a home run. And as I crossed the plate Paul, who was the next hitter, said to me: ‘Now I’ll show you how to hit one, too.’ He did.

“Another time at the Polo Grounds in New York I did the same thing to right field-bounced one into the seats. As I crossed the plate Paul said: ‘Now I’ll show you how to hit a real one.’ He did, too. He hit one over the roof in right field.”

Lloyd, however, was more known for his ability to get on base than his power-hitting skills. He compiled a career average of .316 with 2,459 hits (83 percent of which were singles). He also was a pesky hitter who wouldn’t go down without a fight, proven by his career total of only 173 strikeouts in 18 seasons of play. He was also a mild-mannered individual who never once was ejected from a game.

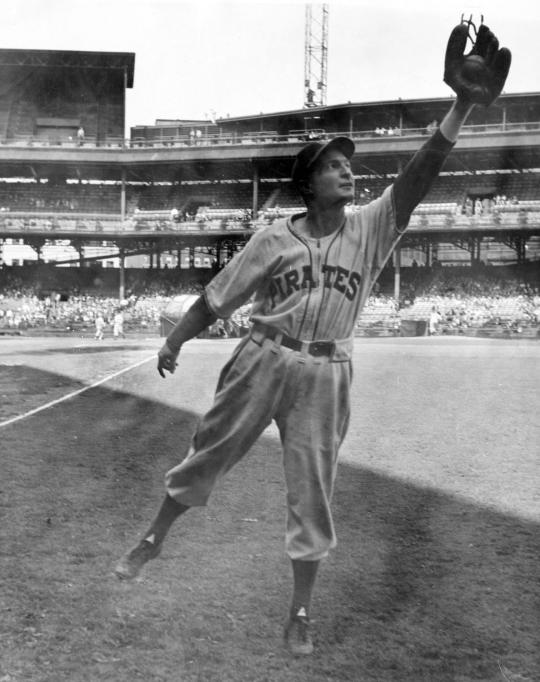

But not all of his skills were on the offensive side. Lloyd was known to have many tools, including his good glove, arm and great speed. During his two years in college at East Central University in Ada, Okla., Lloyd excelled in track. He could run 100 yards in 10 ½ seconds.

Hall of Fame teammate Pie Traynor once pondered how good of a center fielder Lloyd was.

“How good of a center fielder was he? I’d say this: Better than Willie Mays,” Traynor said. “Lloyd played a natural center field and he could go in and grab those balls (behind second base). He was the fastest man in the league. He got a tremendous jump on the ball.”

Not a bad bargain for the Pirates, considering he only cost them the train fare from San Francisco to Pittsburgh, after he was released by the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

His brother Paul persuaded the coach to give him a tryout, and the rest is history.

Kevin Stiner was the spring 2011 Public Relations intern for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum