- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1985 Topps Don Baylor

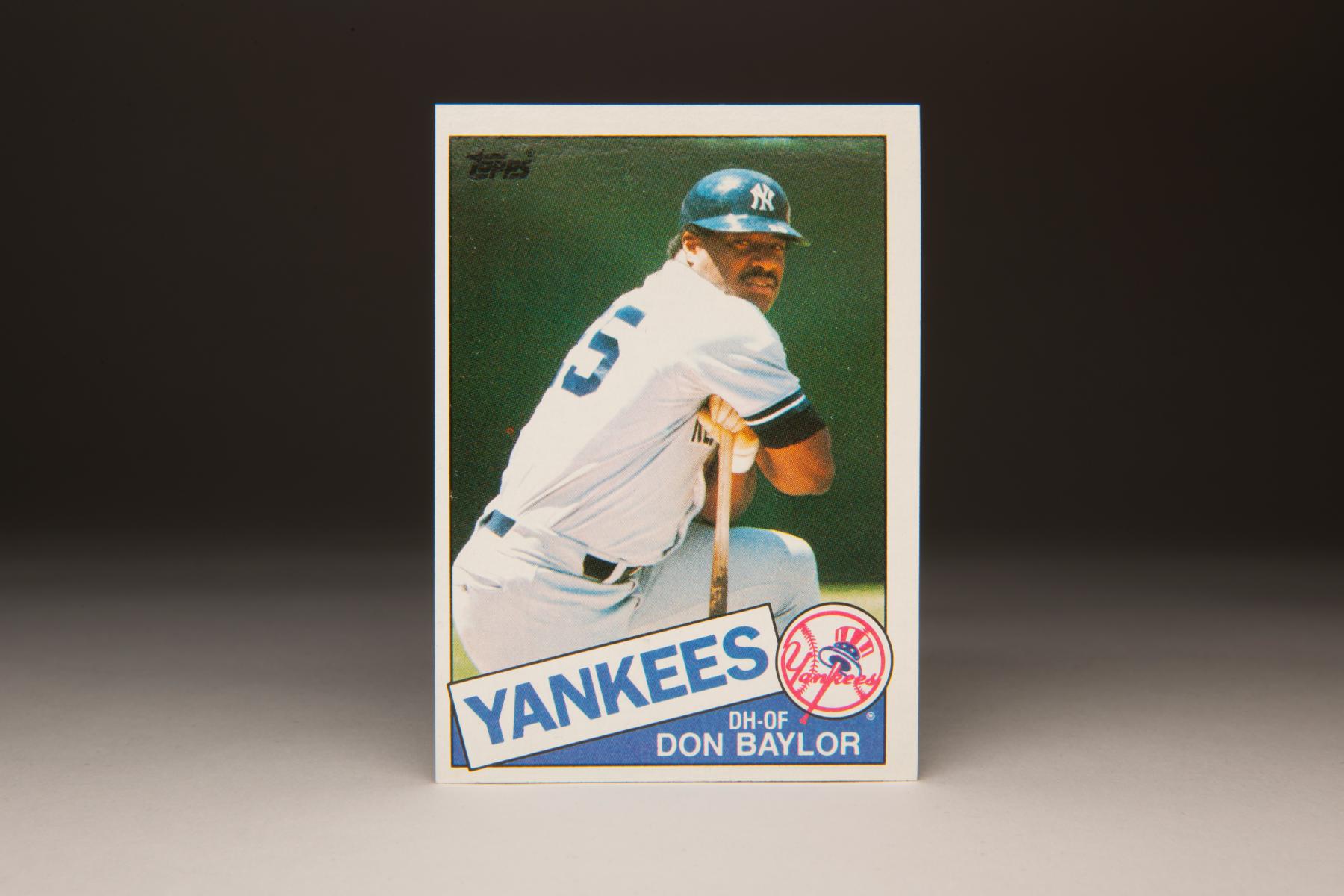

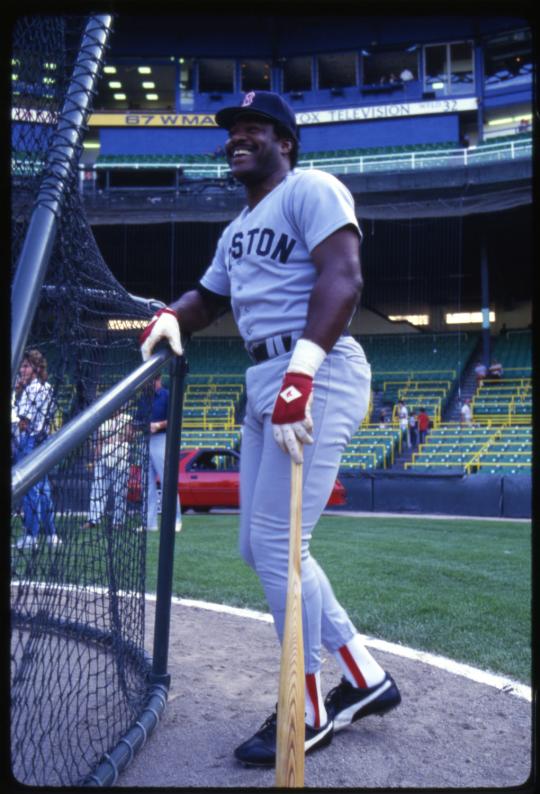

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Don Baylor

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

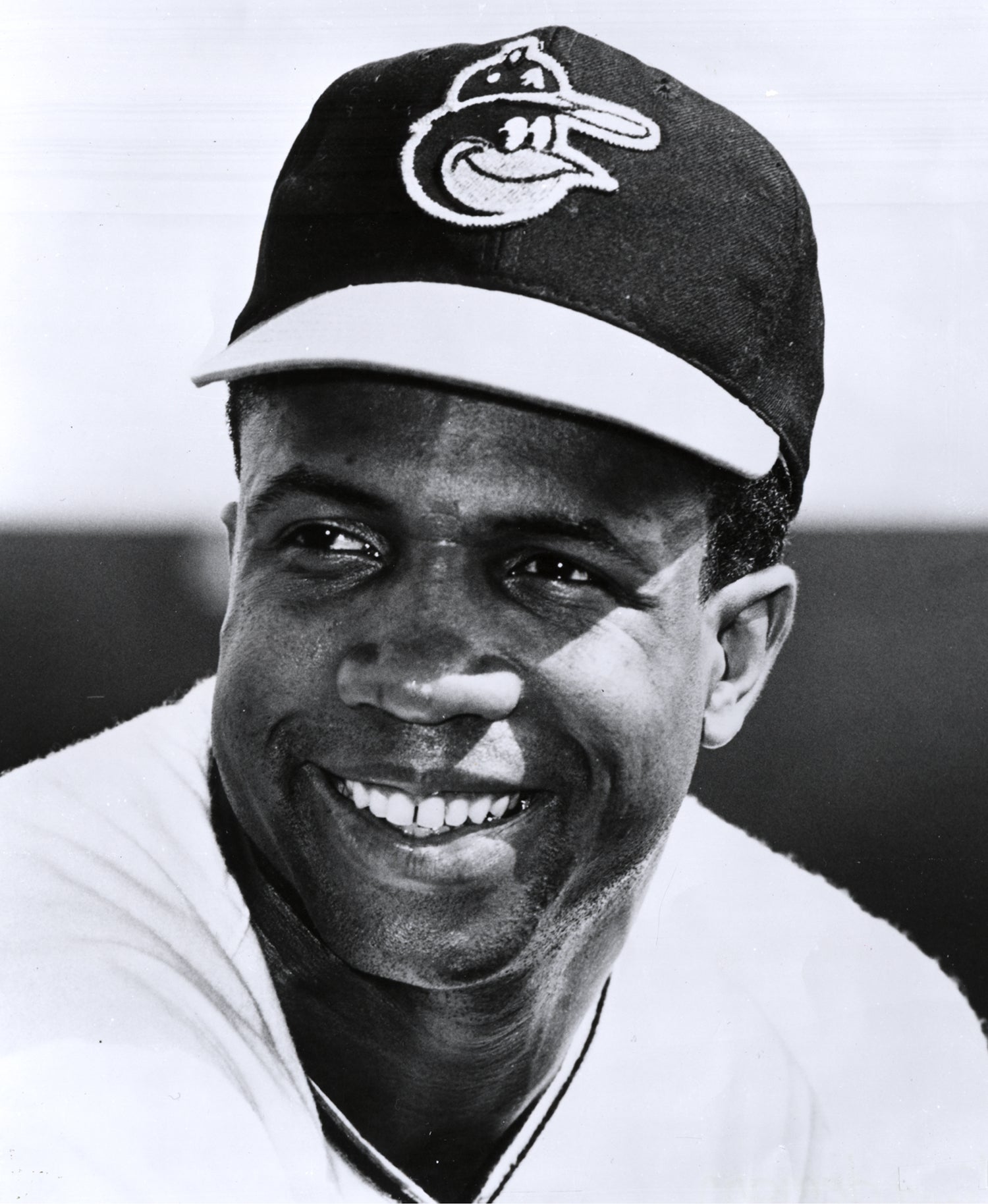

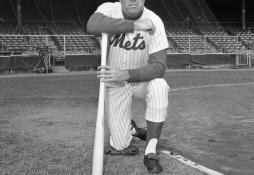

Every once in a while, a baseball card catches the essence of a ballplayer. For me, a perfect example can be found in the 1985 Topps set and the way that it captures Don Baylor. Looking every bit like the block of granite that he appeared to be carved out of, Baylor comes across as intimidating as a ballplayer can look in the on-deck circle. Even the way he tucks his bat under his right shoulder gives you a shiver. In summoning the essence of John Wayne, Jim Brown and Robert DeNiro all rolled into one, the steely-eyed Baylor seems to be telling the photographer, if only with his face and his body language, “What’s the matter with you?” At that point, it wouldn’t have surprised me if the Topps photographer had started running into the clubhouse.

That is not to say that Don Baylor is a cruel and callous guy. But he was as tough as any ballplayer of his era, especially when it came to absorbing pitches that caromed off his body with regularity, or taking out second basemen in a hardened, old-school way that would have made a Chase Utley slide seem tame by comparison. Don Baylor played the game hard and hell-bent for leather, the way that some would like it to continue to be played today.

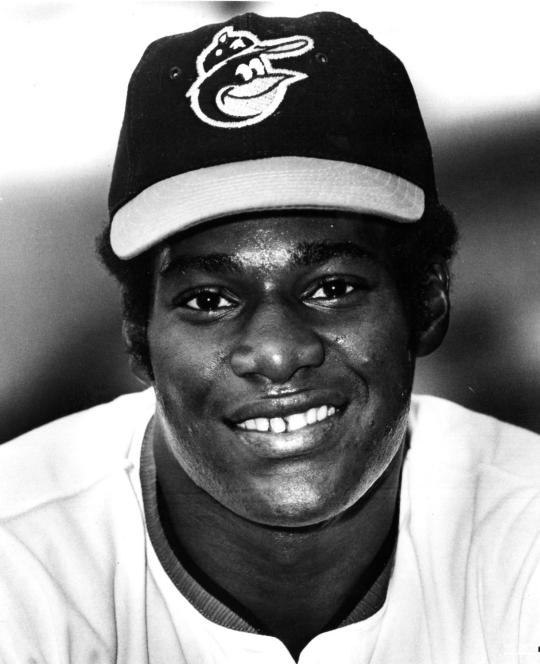

I suspect that the Baltimore Orioles knew all about that toughness when they made Baylor their second-round choice in the 1967 amateur draft. In making that selection, the Orioles thought they might be acquiring the second coming of Frank Robinson. That projection turned out to be overly optimistic, in part because of a high school football injury that damaged Baylor’s right shoulder and limited his throwing. But Baylor was hardly a disappointment. Throughout his minor league career, he proved himself to be a top-tier prospect. He could run, hit, hit with power, and track down fly balls in the outfield.

By 1970, Baylor was in Triple-A - and flourishing. Putting in nearly a full season for the Rochester Red Wings, Baylor hit .327 with 22 home runs and 26 stolen bases. The Sporting News named him Minor League Player of the Year, confirming his status as an elite prospect on the cusp of making the major leagues.

At the tail-end of the 1970 season, the Orioles gave Baylor an eight-game look. Baylor struggled, hardly an uncommon occurrence for a young player making his big league debut. Yet, he remained confident. “If I get into my groove,” Baylor told a reporter one day, “I’m gonna play every day.” Some of his Orioles teammates, picking up on his choice of words and his unusual level of confidence, sarcastically decided to give him the nickname of “Groove.” This was typical behavior from the Orioles, who developed baseball’s leading “Kangaroo Kourt” during that era and enjoyed levying fines against teammates for silly infractions.

As well as Baylor had played at Triple-A in 1970, he found little room for advancement with the power-packed Orioles. Not only did the Orioles win the World Series in 1970, but they already had four quality outfielders in Robinson, center fielder Paul Blair, and left fielders Merv Rettenmund and Don Buford. With the designated hitter rule still two years away from adoption, Baylor had nowhere to go but back to the minor leagues.

Playing at Triple-A in 1971, Baylor practically repeated his huge numbers of the previous season, and received only a one-game look in Baltimore. Clearly, something needed to give in order to clear the logjam and create some space for Baylor.

The break that Baylor needed came at the 1971 Winter Meetings, when the Orioles agreed on a blockbuster deal with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Principally, the O’s gave up Frank Robinson, sending him to LA for a package of young talent headlined by top pitching prospect Doyle Alexander.

The trade of Robinson didn’t immediately clear Baylor for a starting role in Baltimore’s outfield, but it did give the top prospect a place on the 25-man roster. When Rettenmund, Buford and Blair all slumped in 1972, Baylor earned plenty of playing time and emerged as Baltimore’s most productive outfielder. He hit 11 home runs and stole 24 bases, giving the aging Orioles a much-needed boost of speed.

Baylor didn’t play every day for the Orioles in 1973, either, but he did appear in 118 games, stole 32 bases, and posted an OPS of .794. He also showed himself to be an aggressive hitter who crowded the plate. Never one to flinch on inside fastballs, Baylor led the American League with 13 hit-by-pitches.

Baylor soon drew the admiration of Orioles manager Earl Weaver for the way that he ran the bases, in particular his tendency to apply ferocious takeout slides at second base. “He gets down to second base as fast as anyone,” Weaver told the Sporting News. “Baylor doesn’t [slide hard] for himself. He does it to keep the inning alive.”

On one play, Baylor ran over Cleveland Indians second baseman Angel “Remy” Hermoso, knocking him out for three months because of a knee injury. Feeling terrible about the incident, Baylor phoned Hermoso in the hospital, but the Indians felt that Baylor had executed a clean slide with no malicious intent.

In 1975, Baylor more than doubled his home run production (hitting 25 blasts), lifted his OPS to .849, and earned some support for American League MVP. At the age of 26, Baylor had arrived as both a legitimate power source and dangerous base stealer.

That also turned out to be Baylor’s final season in Baltimore. A series of court decisions and a new collective bargaining agreement had created free agency. Baylor, like many other stars, would become a free agent at the end of the 1976 season. The Orioles, seeing a chance to acquire another impending free agent, Reggie Jackson, decided to part with Baylor. The O’s sent Baylor, right-hander Mike Torrez, and a minor leaguer to the Oakland A’s for Jackson and accomplished left-hander Ken Holtzman.

Most scouts favored the Orioles in assessing the deal. But Baylor did fit into the system preferred by new Oakland manager Chuck Tanner. Realizing that the newly fashioned A’s would have less power to rely on, Tanner encouraged his team to run at all times. Giving all of his players the green light, Tanner watched the A’s set an American League record by stealing 341 bases, or an average of more than two per game. No one was more emblematic of their wild running attack than Baylor, who stole 52 bases, a total that he would never again come close to approaching.

Baylor did well in creating havoc on the bases for the A’s, but his batting average and power both suffered. He struggled badly at the Oakland Coliseum, where the expansive foul territory and poor sight lines tended to weaken productive sluggers like Baylor.

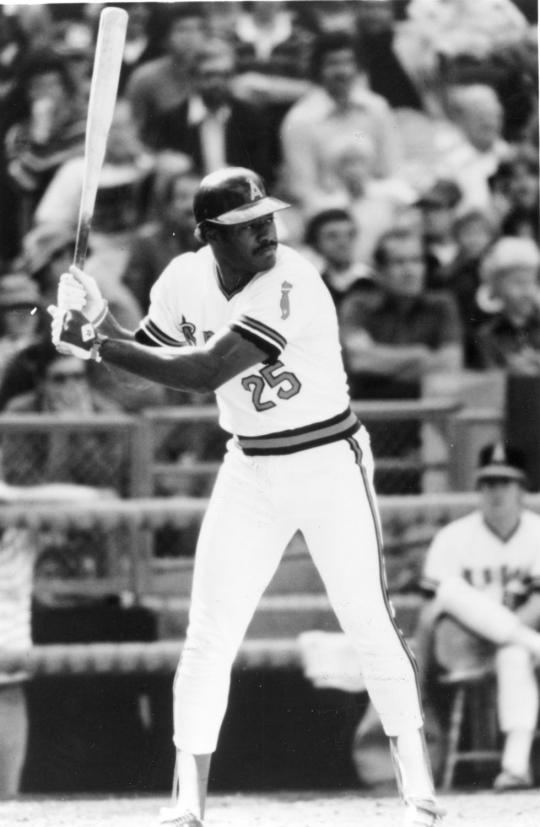

Even if Baylor had hit better, it’s still likely that A's owner Charlie Finley would have failed to offer him a new contract. Baylor hit the open market running, signing a massive six-year contract with the rival California Angels. Baylor remained productive. Doing most of his damage as a DH, Baylor hit 25 home runs and stole 26 bases in 1977.

Baylor also impressed the Southern California media with his hard-nosed approach to the game. They took note of his hustle, his aggressive baserunning and his ability to vault second basemen and shortstops into somersaults on potential double play balls. Other than perhaps Kansas City’s Hal McRae, no player took out middle infielders with more ferocity than Baylor. A future Angels teammate, Rick “The Rooster” Burleson, would call Baylor the toughest baserunner in the league, ahead of McRae, George Brett, Al Bumbry, and Ron LeFlore.

His reputation firmly in place, Baylor would fare even better in 1978. Feeling more comfortable in his second season with the Angels, Baylor reached career highs with 34 home runs and 99 RBIs, and lifted his OPS to .804.

Still, Baylor’s numbers would pale in comparison to what he accomplished in 1979. For the first time in his career, he batted over .290. He clubbed 36 home runs, led the league with 139 RBIs, and slugged .530, pushing the Angels to their first division title and postseason appearance.

Though his selection has become much debated by Sabermetricians in subsequent years, Baylor won the American League MVP. It’s a myth that Baylor became the first fulltime DH to win the MVP - he appeared as a DH only 65 times - but his ability to hit for both average and power clearly won over the voters. Without question, Baylor had arrived as a major league star.

The 1979 season represented the apex of Baylor’s career. The following summer, injuries robbed him of much of his power. Plagued by a broken wrist and a dislocated toe, he hit only five home runs and slugged a mere .341. He then bounced back with two solid seasons, including 24 home runs in 1982.

Though Baylor was still a productive player, he was now 33. With his contract having run its course, he was again eligible for free agency. The Angels made little effort to sign him, standing by as Baylor took his heavy bat back to the East Coast, signing with the Yankees.

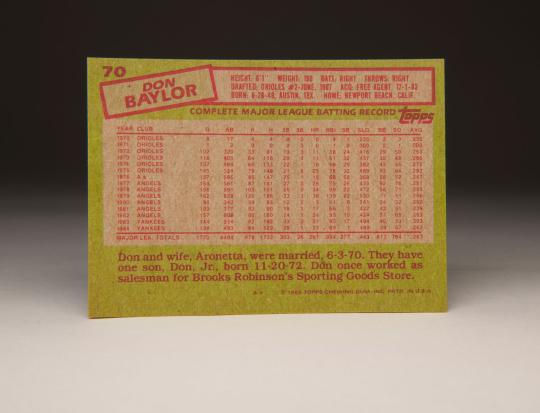

By now Baylor looked much different than he had at the beginning of his career. With at least 30 pounds of additional weight, mostly muscle, Baylor took on the look of a behemoth. But the Yankees needed someone to play first base, so they gave the veteran a tryout in Ft. Lauderdale. Lacking both range and soft hands, Baylor handled the position poorly in workouts. Realizing that he could not play first base on a full-time basis, the Yankees made Baylor their primary DH. Baylor hit 21 home runs and slugged .494. As a bonus, he hit .303, batting over .300 for the first time in his career.

Despite being a pull hitter at Yankee Stadium, where the Death Valley dimensions ruined many a right-handed slugger, Baylor remained productive over the next two seasons. But he grew disenchanted with the atmosphere in New York, in particular the managerial style of Billy Martin. Baylor became such a vocal leader against Martin that the Yankees hired Willie Horton as their “tranquility coach.” The Yankees hoped that Horton would neutralize Baylor’s influence in the Yankee clubhouse.

When it became apparent that Baylor would soon become a platoon player, he asked for a trade at the end of the 1985 season. The Yankees tried to oblige him, reaching agreement on a blockbuster trade that would have sent Baylor to the Chicago White Sox for Carlton Fisk, but Baylor exercised his no-trade clause. He said he would only accept the deal if the White Sox satisfied some of his specific financial demands. It seemed like a strange move on the part of Baylor. He had practically demanded a trade, the Yankees had satisfied the request, and now Baylor wanted no part of the White Sox.

Baylor reported to the Yankees’ spring training camp in Ft. Lauderdale, but he remained on the trade block. In late March, the Yankees finally found a new suitor, but it was a deal that GM Clyde King made only because of the insistence of owner George Steinbrenner. The Yankees sent Baylor to the rival Boston Red Sox for another DH, the left-handed hitting Mike Easler.

With his tendency to pull pitches and hit fly balls, Baylor proved an ideal match for the unusual dimensions of Fenway Park. For the season, he hit 31 home runs, giving the Red Sox yet another right-handed slugger, in back of Jim Rice, Dwight “Dewey” Evans and Dave Henderson. As an added bonus, Baylor was hit by pitches 35 times, which represented a career high. (With 30 home runs and 30 hit-by-pitches, it might have been the strangest 30/30 season in big league history.)

With the Red Sox, Baylor exerted an unusual amount of leadership for a player. When Texas Rangers coach Tim Foli initiated some severe bench jockeying against Oil Can Boyd, the 37-year-old Baylor walked out of the dugout between innings and confronted Foli, telling him to shut up. Not surprisingly, Foli kept quiet for the rest of the series.

In 1987, the Red Sox fell out of the pennant race and traded him to the Minnesota Twins, who were headed to a Western Division title. Joining the team just in time to be eligible for the postseason, Baylor became a force during the World Series. He quietly hit .385 with a home run and three RBIs, as the Twins won the Series in seven games.

Released by the cost-conscious Twins during the winter, he signed with the A’s, who made him a part-time DH. Baylor didn’t hit much during the regular season or the postseason, but he did make his third straight appearance in the World Series, all three coming with different teams.

At the end of the World Series, Baylor opted to retire, ending a long 19-year playing career and leaving the game as its most prolific clay pigeon (267 hit-by-pitches). Baylor wore the latter honor like a badge of courage.

Baylor remained in the game as a coach. In 1993, he became the first manager in the history of the Colorado Rockies. After two poor finishes with the expansion Rockies, he led the team to three consecutive seasons with better than .500 records. When the Rockies slumped in 1998, Baylor lost his job.

Fresh off the firing, Baylor became the batting coach for the Atlanta Braves. He did particularly good work with a young Chipper Jones, helping his star protégé improve as a right-handed hitter. The acclaim earned him a job as the manager of the Chicago Cubs, but he took criticism for his handling of the pitching staff and was fired by the front office in the middle of the 2002 season.

A year later, after he had joined the New York Mets’ coaching staff, Baylor received far worse news when he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. The disease often kills patients within five years of diagnosis. Not so with Baylor. He found a way to fight the disease before passing away on Aug. 7, 2017.

When you’re Don Baylor, you’re simply not going to go down without a fight.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame