"Umont, Goetz and Rommel right now may see more accurately than some umpires who were not advised to supplement their optics."

- Home

- Our Stories

- Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Yelling at an umpire that he needs glasses has been a common refrain of disgruntled baseball fans for as long as there have been umpires and disgruntled baseball fans. But nearly six decades ago, this favored chant took on new meaning when a brave arbiter became a trailblazer in his profession.

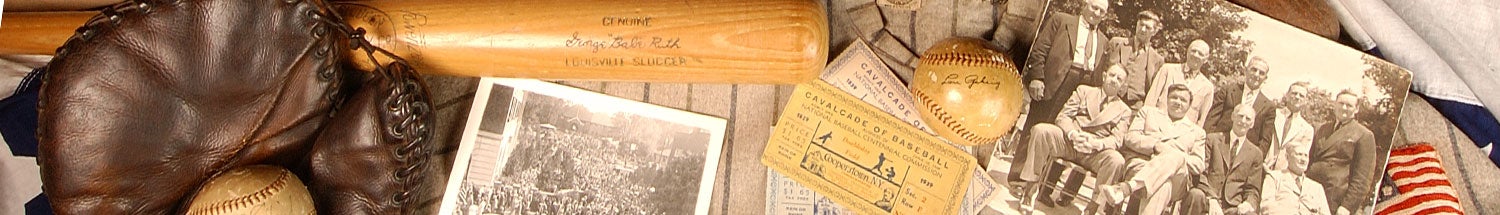

Today, evidence of this historic undertaking resides in Cooperstown in the collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

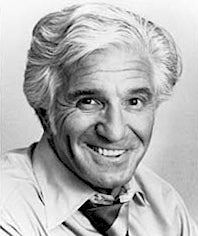

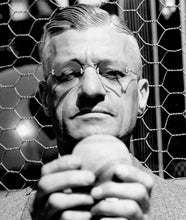

On April 25, 1956, newspapers across trumpeted the news that Frank Umont had on the previous day become the first big league umpire to wear eyeglasses in a regularly scheduled game. Suddenly this early-season American League contest between the Detroit Tigers and host Kansas City Athletics took on special meaning, but those in attendance, both on the field and in the stands, took little notice of the bespectacled ump working at second base who didn’t have a close decision that afternoon.

After the game, a 7-4 Tigers victory, a number of sportswriters went to the umpire room in Municipal Stadium to interview Umont but he didn’t want to talk.

“I just don’t think I’ll say anything,” Umont said.

Instead, Umont referred the newsmen to Charley Berry, a fellow umpire on the crew as well as a former big league catcher.

“Why shouldn’t he wear glasses as well as anyone else? The players do,” said Berry. “It’s as simple as this: Frank needed a slight correction in his left eye. So he asked Will Harridge (president of the American League) whether it would be all right to get glasses. Harridge said he believed it was the right thing to do.

“It has nothing to do with Frank’s judgement. He could see and umpire without them and do a good job. But he needs a little correction in one eye. So he got it.”

According to reports, Athletics manager and future Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau didn’t even notice Umont was wearing glasses.

“It’s no disgrace to wear glasses, is it? If it makes him a better umpire, I’m for it,” said Boudreau. “More power to him.”

Tigers third baseman Ray Boone agreed, saying, “Ballplayers wear ‘em and nobody thinks anything about it. Why not umpires?”

Ballplayers who wore glasses during this era included Del Ennis, Stan Lopata, Bill Virdon, Jim Konstanty, Dave Sisler, Jim Brosnan, Roy McMillan and Dom DiMaggio.

Prior to the game, Umont, who was advised to wear glasses after a league-sponsored eye exam the previous winter, said, “I expect to be ribbed about my glasses, but I don’t expect it will worry me.”

One reason the 39-year-old Umont may not have had anything to worry about was his former profession as a fierce 6-foot-1, 220 pound lineman with the New York Giants in the early 1940s.

In a New York Times sports column on May 13, 1956, Arthur Daley wrote about the longstanding taboo of umpires wearing eyeglasses on the field.

“It is reassuring to learn that Frank Umont, one of the younger and better umpires, courageously has taken to wearing glasses while working. What’s wrong with that?,” Daley wrote. “Ballplayers have been questioning the vision of umpires for so long and with such vehemence that the Men in Blue have flinched at the thought of donning cheaters. They seemed to regard them as an admission that their eyesight was less than perfect. From the standpoint of pure logic, however, arbiters in spectacles are operating on firmer ground.

“Even umpires are human, opinions of ballplayers to the contrary. As such they are subject to all human frailties, including occasional traces of astigmatism.”

A month after Umont, an American League umpire for 20 years (1954-73) who worked four World Series, four All-Star games and a League Championship Series, passed away on June 20, 1991, his daughter, Cathy Glennon, wrote a letter to the Hall of Fame.

“I am offering to the Hall of Fame the glasses my dad wore as the first umpire to wear glasses,” Glennon’s letter read in part. “They are in good shape and I feel they might be of interest and a valuable addition.”

Recent research reveals there was at least one big league umpire in the 19th century, Billy McLean, who wore glasses. In fact, Umont’s notoriety for this singular achievement was short-lived even at the time, as the day after news of his eyeglass-wearing feat was reported, two more big league umpires came out to say that they had each worn glasses earlier that same year.

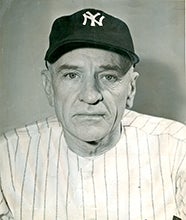

Ed Rommel, the winner of 171 games as a big league knuckleball pitcher (1920-32) before embarking on a 22-year career (1938-59) as an A.L. umpire, claimed he had worn glasses during the second day of the ’56 season, a 9-5 New York Yankees win at Washington’s Griffith Stadium on April 18.

“I believe it was the first time in the majors and no one noticed them,” said the 58-year-old Rommel, who umpired at third base on this day. “The doctor this winter said I didn’t need glasses unless my eyes bothered me. I decided to get them anyhow for night games, when I’m on the bases. That’s when seeing is toughest.

“I don’t need them for anything close – like reading, or calling balls and strikes.”

Washington’s Clint Courtney, the American League’s only bespectacled catcher at the time, saw no problem, adding, “Sure it’s okay for umpires to wear them. If a player can see better with them, an umpire definitely can see better.”

But Yankees Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel was less diplomatic, commenting on the disclosure that two AL umpires are wearing glasses: “They rob you for 20 years and then they put on glasses.”

During the offseason prior to the 1956 season, Harridge made it clear to Junior Circuit umps Umont and Rommel that they were allowed to wear glasses with league approval.

“At our regular winter rules meeting with the umpires last January, we decided upon an eye examination for the entire umpire staff. Excellent reports were received with two exceptions,” Harridge explained. “Frank Umont was advised to wear glasses for a time, the physician explaining that glasses probably would correct a slight defect in one eye and that he possibly could discontinue wearing them after a time.

“Ed Rommel, a veteran of our staff, also was advised to wear glasses should his eyes give him trouble this season,” he added. “We feel our action in holding the examination was practical and in the best interest of the game and the league likely will hold similar examinations each winter.”

On the same day as Rommel and following on the heels of the announcement that Umont first wore glasses, National League umpire Larry Goetz said he had donned specs on April 22.

“I started wearing glasses Sunday in Philadelphia,” said Goetz, who would ump in the Senior Circuit from 1936 to 1957. “My eyes are fine but I find I can follow the ball to the outfield better with glasses.”

But Goetz admitted he did not ask National League President Warren Giles for permission to wear glasses.

“I didn’t think it was necessary,” Goetz explained.

The Sporting News, the self-proclaimed “Bible of Baseball,” editorialized on May 9, 1956 about the recent revelations concerning Umont, Rommel and Goetz.

“The vision of none of the three umpires needs more than slight correction, which the spectacles will provide. But even if their handicaps were greater, they would not be one bit less competent as arbiters so long as the glasses enabled them to see as well as anybody else.

“In many fields of activity, from the most exciting surgery to the most complicated chemistry, glasses are worn as a matter of course. If a fellow needs them, he uses them – and no one questions his ability to see through them.

“The fact is that folks who wear glasses often enjoy better vision then fellow workers who depend on unaided eyesight. Umont, Goetz and Rommel right now may see more accurately than some umpires who were not advised to supplement their optics.

“If there is in baseball one iota of prejudice against glasses, the sooner it is banished the better. If a bespectacled doctor can operate successfully on the human heart, it is absurd to argue that a bespectacled umpire can’t see whether a runner is safe or out.”

Over the recent past, umpires to wear glasses have included Al Clark, Frank Pulli and Lee Weyer. Where at one time “Three Blind Mice” would be played by the ballpark organist as the umpires came onto the field, today the novelty has worn off.

“Maybe umpires fear that their job is so exacting, so demanding of sharp-eyed decision, that any admission of age, any clue, such as eyeglasses, would hasten their enforced retirement,” wrote 1978 J.G. Taylor Spink Award honoree Dick Young in a May 1974 column. “This makes it a matter of security more than vanity.

“That is an outdated fear. There no longer is a stigma attached to astigmatism. Ballplayers wear eyeglasses in the field, and if they can do it, why not umpires?”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Spink Award Winners

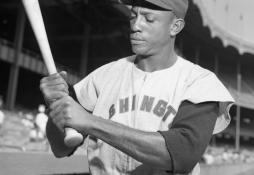

Reproductions

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum features a collection of nearly 250,000 photographs like this one. Reproductions are available for purchase. To purchase a reprint of this photograph or others from the Photo Archive collections, please call (607) 547-0375 or email jhorne@baseballhall.org. Hall of Fame members receive a 10-percent discount.