The two things I'm proudest of in my life, is that I became a Marine pilot and that I became a member of Baseball's Hall of Fame.

- Home

- Our Stories

- Ted Williams Looks Back

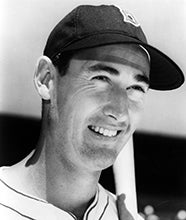

Ted Williams Looks Back

A Visit with Teddy Ballgame

In February 2000, the Hall of Fame had a chance to sit down with hitting legend Ted Williams in his hometown, San Diego, California. Over the course of an hour, Williams talked about topics ranging from his first love - hitting - to his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

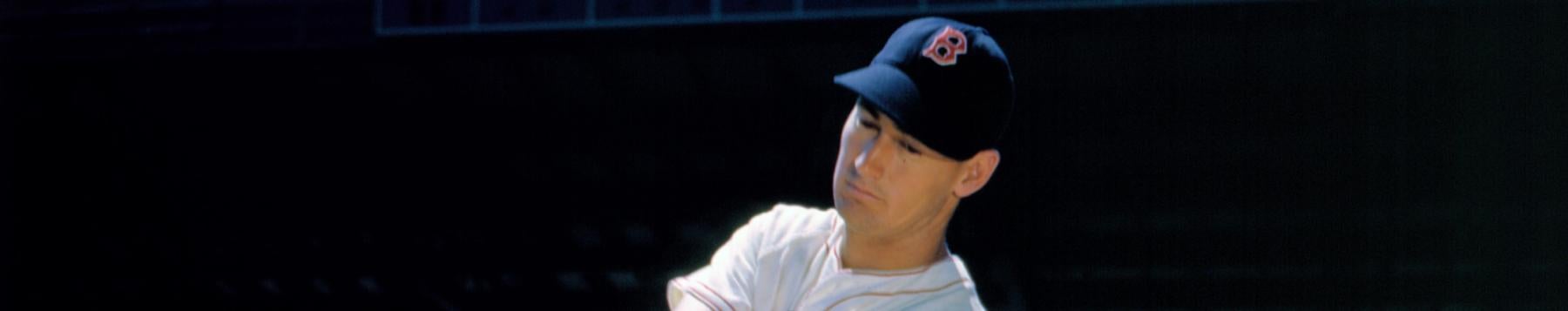

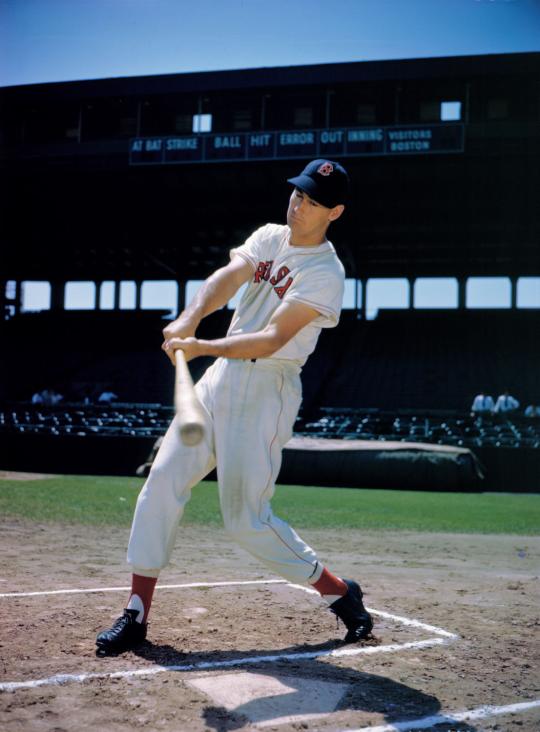

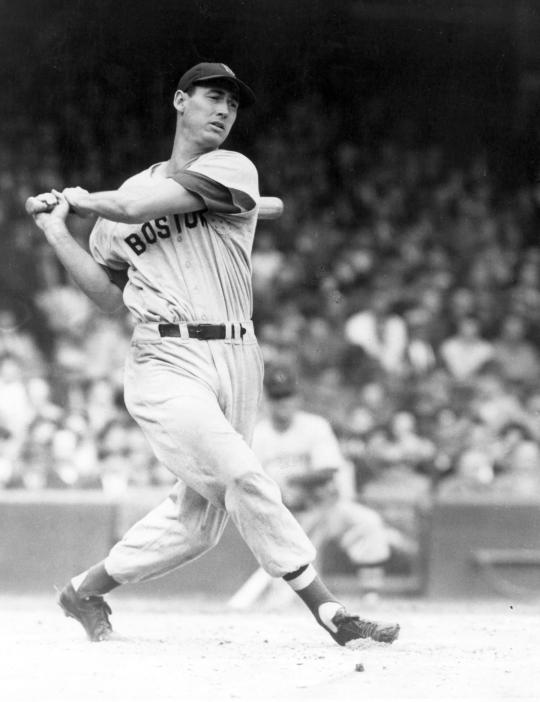

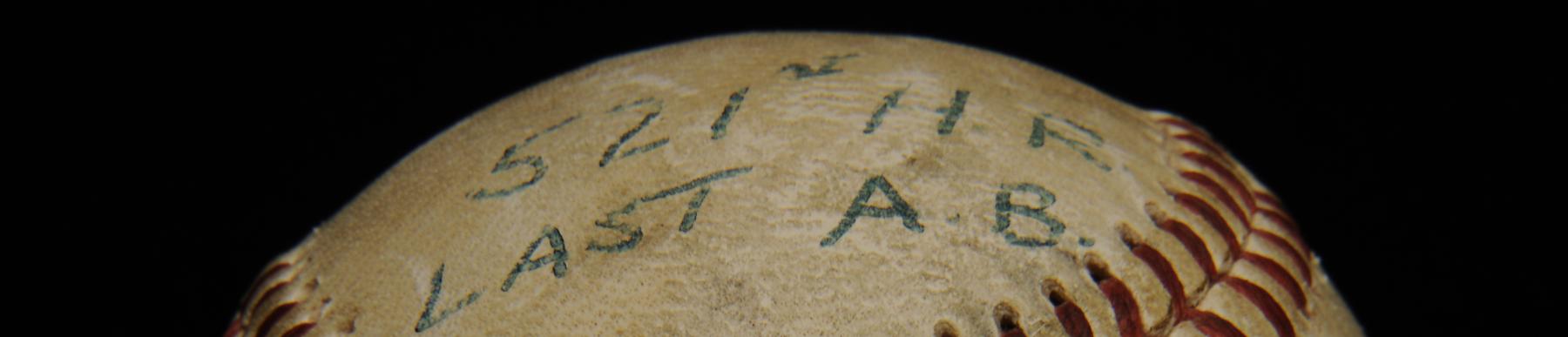

Everyone knows about his many accomplishments on the baseball diamond. There were two MVP awards, two Triple Crowns, six American League batting championships, 18 All-Star Game selections, 521 home runs and, of course, one .400 season.

Williams' prowess as a fisherman is also widely documented, as evidenced by his place in two Fishing Halls of Fame. But one accolade that few people know about is one that Ted earned in high school. Bob Breitbard, one of Williams' closest childhood friends, remembered this achievement. "When we graduated from Hoover High, the graduation was held in the front of school," said Breitbard, the founder and president emeritus of the San Diego Hall of Champions in Balboa Park. "Floyd Johnson, our principal, handed out the diplomas and then announced that he had two special awards to present: one to Ted and one to me. We were named co-champions for typing the most words - 32 per minute - without an error." So when counting all of Williams' honors, remember, he was also a master of the keyboard.

Hall of Fame:

We're sitting down with Ted Williams today here in his native San Diego and Ted, it's a pleasure to be with you.

Ted Williams:

It's certainly nice to be with you fellas who represent the greatest showplace that Baseball has - the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. All the history that's there certainly catalogs the whole game, probably as well as any sport has ever done.

HOF:

Growing up in the North Park section of San Diego, you took a liking to baseball early on, by the second grade or so. Tell us about Rod Luscomb and North Park playground.

TW:

Rod Luscomb was the playground director. He was in charge of North Park playground, which was two blocks from my house. He had been a great athlete himself in Arizona, where he went to school. He was really a frustrated old ballplayer. He wanted to play, but was maybe not quite good enough at that time. But he was a hell of an athlete. He loved to be out on the playground and he certainly had a customer in me because I loved to be there too. I was a little better for my age than some kids and we had quite a few competitive little games among ourselves. He brought enthusiasm with his playing. He never really instructed me to do anything, except he played hard against me and I played hard against him. I was a teenager and he was probably 28. He loved his work and I loved being on the playground. With him being so much better than I was, I liked that, because it gave me a chance to get up against a little better competition than what we had in junior high school.

HOF:

Is it fair to say you practiced and practiced and practiced as a youth?

TW:

No, I didn't even consider playing baseball practice. The most fun I ever had in my life was if I was hitting a baseball and if I could hit one - pow! - gee, that felt good to me. And as you get better at something you tend to like it a little more. And the practice, that was the most fun I ever had in my life, and I laugh because I got so much credit for it.

If a young kid is tearing down the fences, I believe in pushing him a step further. Put him in a tougher league. Don't let him burn this league up; he's proven he can do that. If you keep pushing him all the time where nothing is really easy, he's got to bear down to succeed, to get better, and compete. I think he progresses better in the long run this way, no question.

HOF:

There's a great story about you carrying your bat from class to class in school. Was anyone else carrying a bat in school?

TW:

No, I can't think of anyone else. The reason I carried the bat was because it was a school bat. I got there early enough so I could be there to get the bat and the ball and wait for the kids to play.

HOF:

As a child, did you have any Baseball heroes or any heroes?

TW:

No, I lived in San Diego, 3,500 miles from New York City. Everything came out of New York. Of course I read the papers and the accounts of the games and certainly I knew of (Babe) Ruth, (Lou) Gehrig, (Al) Simmons and (Jimmie) Foxx. When they didn't show movies on Saturdays or Sundays, they might have some shots of Major League games where somebody hit a home run, somebody drove in a winning run or somebody pitched a great game. And of course, those were the players I got to know by name. There were a lot of great players I did hear about - Bill Terry, Mel Ott, Lefty Grove. Of course, there was Carl Hubbell, Red Ruffing and Lefty Gomez - they were big pitchers then.

HOF:

Red Ruffing started for the Yankees in your major league debut, which was at Yankee Stadium, with Babe Ruth in attendance.

TW:

First game, first time, I struck out. One of my teammates (Jack Wilson) kind of thought I was a little bit cocky. I didn't mean to be but apparently I acted that way. He came all the way down from the end of the dugout, I could see him coming and I couldn't believe what he'd want being up in our end of the dugout. I was up by the water fountain and the bat rack and here he comes right for me. Then he says to me, 'What do you think of the big leagues?' Well, I'd been up once and I'd struck out once and I had to think it was pretty tough. I gave him a little sass but I also said this, I said, 'I KNOW I can hit that guy.' Well it later proved that I did hit 'em pretty good. (Williams doubled in his second at-bat).

But that first time Ruffing was sneaky fast. He threw with a little 'umph' and boy, there it was! If you didn't realize this guy could throw and do so with less motion and effort and excitement, then it was by you. My first key on him was that this guy is sneaky and he is faster than he looks. Now I've run into quite a few pitchers that I thought were faster than they looked. One was Billy Pierce, who was a little guy. (Dizzy) Trout was another. He was a big, strong guy, but didn't throw a lot of effort into it. But boy, he could throw the ball too.

HOF:

Not only could you hit, but you were also a very good pitcher at Herbert Hoover High School. You went 16-3 as a senior with a 23-strikeout game.

TW:

I think you're a hell of a guy to bring all that stuff up because old ball players, especially old outfielders, like to hear about their exploits on the mound. And the pitchers, they love to hear about any hit they got two years ago. Yeah, I was a pretty good little pitcher and I had good breaking stuff. I really think I had more fun in high school pitching than I did hitting. Hitting was still kind of tough to do, but if I could get my curve over and get my stuff over, I could get the guys out.

HOF:

Did you have any thoughts of being the next Babe Ruth as a kid?

TW:

No, not a bit, not a bit. I knew who Babe Ruth was and I'd heard more about him than anybody else.

HOF:

Red Sox general manager and Hall of Famer Eddie Collins scouted and signed you, along with Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr, during your second year in the Pacific Coast League. What do you remember about first meeting Collins?

TW:

Well, Eddie Collins was one of the great players and he was on the White Sox when they had their big scandal. He played with Joe Jackson. Eddie Collins had played against Babe Ruth. He had played against all the great American League players then. In fact when Mr. (Tom) Yawkey bought the Red Sox, he said, 'If I can sign Eddie Collins to come with me, I'll buy 'em.' Well, he bought the club and got Eddie Collins with them. He was a wonderful man. He was one of the vice presidents and he always wanted to talk about the Bambino or he wanted to talk about Gehrig or he wanted to talk Simmons, possibly or he wanted to talk about Grove or Ruffing. So Eddie Collins kept talking about the big players. Finally one day in our little house, I was sitting in the living room with him, and we'd been talking. I casually said, 'Tell me about Joe Jackson.' Well I'll never forget what he did. He dropped his head when I said 'Joe Jackson,' and he thought for maybe three or four seconds, then he looked up at the ceiling and said, 'Boy, what a player he was.' You could just see by his timing, his look and the way he said it that there was no question in his mind how good Joe Jackson was.

HOF:

After you signed with Boston they assigned you to Minneapolis in 1938, where you met another Hall of Famer, Rogers Hornsby. Hornsby, of course, was a three-time .400 hitter in the 1920s. You won a Triple Crown that year and had a great Major League career and thus the moniker 'the greatest hitter that ever lived.' What did you learn from the sweet-swinging right-handed hitter?

TW:

Well, you know Hornsby was a tough guy and he had problems with ownership. He was a cantankerous old guy but he treated me like I was a young son that he was having fun with. He was absolutely great. Boy I loved him. He didn't really work on the mental approach with me as much as just talking about hitting. His philosophy and understanding of how he hit so well I didn't really agree with, even at a young age. For example, he said, 'When the ball's outside, I step outside, then I hit it. On a ball inside, I open up and I hit the ball to right field.' You can't do that really, because you don't know where the ball is or what it is until it gets 10 feet from the plate. You can't make that adjustment that fast.

So, I listened to him, I always tried to listen to everybody because sometimes they'll say something that sounds all right and I'll say to myself, 'Gee I didn't realize that.' Then I might go out and try it. But once in a while I'd get a little kind of something. I'd hear somebody say, 'Boy, he's got quick wrists.' I didn't know if that was real good or real bad, but he'd notice that. And I thought to myself, 'He thinks I'm quick now, wait until the next time he sees me!'

It was little things like that you pick up and you listen to everybody and you try things that you think might help you. You don't have to spend five seasons in a rut with something that was lousy to start with. You've got to pick it up a little bit faster than that and say, 'Yeah, that helps me, I like that.' You separate the good from the bad, keep the good. Occasionally you might try the other things.

HOF:

What did you think of Ty Cobb?

TW:

Like Hornsby, he too was absolutely great. Why? I don't know. I never did train with Ty Cobb, but I sure had a chance to talk with him quite a bit. He was a strict guy, a tough guy. Everything included, he and Hornsby were probably the two greatest, outside of Babe Ruth, of course. Cobb wanted everybody to know how good he was and he wanted everybody to know how smart he was. There's no question: he studied what he did and how he had to do it the best way and the most prolific way that he could do it. I don't think .367 will ever be matched.

Cobb was so fast, so big, so strong. He had more 'ginger in his butt' to want to play. I'll always think he was probably as hard of a player and put out as much every day, as any player who ever played. I think Pete Rose was a little like that, too.

HOF:

You always had great respect for your managers. Your first in the majors happened to be your starting shortstop, Hall of Famer Joe Cronin. What was it like having Joe as a manager as a rookie in the majors?

TW:

He was a dream come true for a young kid that thought hitting was everything. Cronin was a good hitter who was always talking about the hitting and never about the fielding or never about the pitching. Cronin could always sum up everything fast. For example, if you're hitting against a high fastball pitcher he'd say, 'Make him come down.' And if we had a sinker ball pitcher that day and a curve ball's in the dirt, he'd say, 'Make him come up.'

HOF:

What were your first impressions of Fenway Park?

TW:

Don't forget Fenway Park was the furthest place from where I lived in San Diego. Here I am on the West Coast and it's on the East Coast. I didn't want to go there. Sure I knew where Boston was, but I'd never been there. Boston had snow and it had cold and longer periods of cold than San Diego. I never did like to play in cold weather much. But, you get used to things. It's probably the greatest break I ever got, that I got to play for Mr. Yawkey, who was an absolute gem of a guy. He was one of the truly great owners in baseball because he thought of the players a lot, he thought of ways to help them. It (buying the Red Sox) was a dream from the time Mr. Yawkey was old enough to realize what 35 million bucks was. He said, 'I'm going to buy a ball club,' and he stayed with it the rest of his life.

HOF:

Prior to Eddie Collins' visit to you in San Diego, New York scout Bill Essick tried to sign you for the Yankees. How might your career have fared had you called Yankee Stadium home?

TW:

Well, there's been a lot of thought about that. Just because Yankee Stadium was closer in right field and I was a pull hitter, you'd think, 'Boy, that's made to order.' I didn't get as many balls to pull in Yankee Stadium with a short fence as I did in Fenway where the fence was long. At least, I got good balls to hit! I've been in little bandbox ball parks and you can be there all week before you get a ball that gets more than an inch off the plate. There's reasons why a small ballpark and a pull field for a hitter can sometimes be even more difficult than if he has the wide open spaces.

HOF:

You hit .399 in Sportsman's Park, you hit .371 in Kansas City and better than .300 in every road ballpark except for Comiskey. What was the toughest ballpark in which to hit?

TW:

I didn't realize I'd hit that well in St. Louis, lifetime. But, I always thought Yankee Stadium was the toughest place to hit because they always said, 'Don't let him beat you,' and they always said, 'Don't let him pull you. If you walk him, what's the difference? He's sitting over there on first base, you have a double play all set up.' So, I got fewer balls to hit, I believe in my career hitting in Yankee Stadium than I did in Comiskey Park.

HOF:

Ted, in 1941, just your third season in the majors, it was so special. You had hit .327 and .344 in your first two years, and in '41 you became the first player to hit .400 since Bill Terry in 1930, and you are still the last to do so. Your slugging average was over .700, you walked 145 times and led the league in home runs. What contributed to this unsurpassed season, and how did you maintain focus the entire year?

TW:

It was the first time it ever happened in my life like that and I was just doing what I was trying to do all the time - hit the ball hard. I think that in all careers, in all outstanding performances - baseball, football, basketball - all of them go in cycles. Now a great player, Joe DiMaggio, hit in 56 straight games that same year, so it's possible that maybe pitching wasn't quite as strong that year. I can't say for sure. I do know there were several guys that hit well that year, so you have to think maybe pitching was at a little lower level, I don't know. First time I ever said that.

HOF:

Ted, you always had a flair for dramatics. At the '42 All-Star Game in Detroit, you homered off Claude Passeau in the ninth inning. You came back and had a phenomenal mid-season classic in 1946 in your home park, Fenway. You went four-for-four with two home runs. Prior to the game, you spoke with Rip Sewell, you asked him to demonstrate his eephus pitch and of course you hit the home run off him. Can you talk a little bit about that?

TW:

What happened is that Bill Dickey and I were sitting on the bench and here comes Sewell. He looked in and he saw Bill Dickey and he saw me there. I don't know what he heard or what he suspected, but he said, 'You're going to get it!' That's all he said, 'You're going to get it!' Of course, we knew what he was talking about because we had been talking about the eephus pitch. It's a ball that just getting it over the plate for a called strike was pretty good. But he could do it. I told Bill, 'Nobody can hit a home run off that pitch.' And Bill Dickey said to me, 'You can.' Well, I just forgot about it and I did hit a home run off of it. That was really the story. He (Sewell) could get that damn pitch over and he didn't throw it harder than a softball, but he could get it called for a strike. And I did hit the eephus pitch. I swung as hard as I could and the wind was blowing out.

HOF:

Ted, just five days later in '46 against the Indians in a twinbill at Fenway, you were five-for-five with three homers and eight RBI in the first game. Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau implemented the famous 'Williams Shift' in game two. When you stepped into the batter box, I know Chicago had tried it a few years earlier, but what were you thinking?

TW:

I was just trying to prepare myself to be ready to hit. Hit it hard, not hit it to the left or not hit it over here. Hit the ball hard. That's all I really ever thought about, just hit the ball hard.

HOF:

1946 was a great season for the Red Sox. They won 104 games and won the pennant. We all know about the heartbreaking loss to St. Louis in seven games. Is there any satisfaction whatsoever in winning a pennant and getting to the World Series?

TW:

Oh, certainly there's a lot of satisfaction. It isn't the ultimate joy of, say winning the World Series, but it's certainly two-thirds of the act. Here we are talking about the only Series I got in. And I did poorly, and I don't know why today. I don't know why.

HOF:

You had two tours of duty in the service, World War II and Korea. In Korea you flew 39 missions and twice could have conceivably lost your life while airborne. How did you deal with the fear of mortality?

TW:

Scared to death, holding on. I sat in the cockpit and I said, 'If there's anybody up there that can help me, now's the time to do it.' I did say that.

HOF:

You loved the Marines.

TW:

The Marines were allotted more planes because they had to keep up with a certain percentage that strengthened the Navy. During the war, they had let the Marines drop a lot, and finally it was time to try to rebuild the Marines. So I was called up and the next thing I knew I was back in reserves and I requested jets. A friend of mine had been in Korea. An old Marine buddy, one of my great friends, Bill Churchum. So I requested jets and I wasn't guaranteed a thing, but that's what I was trying to get. So sure enough, I got jets.

I have to say this: how lucky I've been in life, I know how lucky I've been in life, more than anybody will ever know. I've lived a kind of precarious life style, precarious in sports, flying and baseball. And oh boy. I know how lucky I've been. The two things I'm proudest of in my life, is that I became a Marine pilot and that I became a member of the Baseball's Hall of Fame. I worked hard (at flying). I wasn't prepared to go into it. Then I had to work hard as hard as hell to try to keep going, to try and keep up. I did have reasonable flying abilities. I had cars and I had been running up and down the highways. I had done a lot of shooting. I think that's as great an accomplishment as anything I'd done in my life. The other thing, of course, is that I had a great baseball career.

HOF:

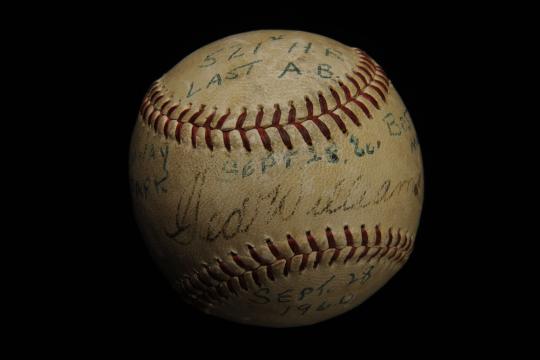

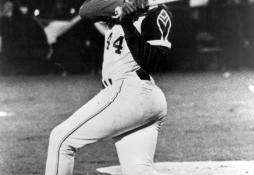

Move ahead to September 28, 1960, your last game. What are your recollections of your final game and your final at-bat and of course, the home run?

TW:

Well, in the first place, I wasn't going to play in New York and I told them that. I said, 'I'm not going to New York to play the last three games. We're out of the pennant and I've had it, I just can't do it.' So nobody said anything about it, but the clubhouse boy knew it because I confided in him in everything. Well, I think the word got out. Curt Gowdy always said he knew that was going to be my last game. Apparently, Johnny Orlando told him. But I went into that game just thinking, 'Well, this is the last game for me.' We were playing Baltimore. (Steve) Barber was a tough little pitcher, but he was wild that day. He walked me that first time up. He didn't even get through the first lineup and they got him out of there. He was walking everybody. So he got out of the game and I was kind of glad of that. I didn't have any ideas about home runs, I was trying to hit the ball hard.

To show you how and why I consider myself the luckiest guy that ever hit, I had hunches and I could guess good and one of them was the last time at bat. I'd hit two balls damn good that day and I thought they were going to go, but they didn't. So, here I am, the last time at bat. We're two runs behind, nobody on, I got the count one and nothing and now Jack Fisher's pitching. He laid a ball right there, I don't think I ever missed in my life like I missed that one, but I missed it. And for the first time in my life I said, 'Oh Jesus, what happened, why didn't I hit THAT one?' I couldn't believe it. It was straight, not the fastest pitch I'd ever seen, good stuff. I missed the swing and I thought…I didn't know what to think because I didn't know what I'd done on that swing. Was I ahead or was I behind, it wasn't a breaking ball and right in a spot that, boy what a ball to hit. I swung, had a hell of a swing, and I missed it. I'm still there trying to figure out what the hell happened. Then I could see Fisher out there with his glove up to get the ball back quickly, as much as saying 'I threw that one by him. I'll throw another one by him.' And I saw all that and I guess it woke me up, you know? Right away I assumed, 'He thinks he threw it by me. He thinks he threw it by me!' The way he was asking for the ball back quick, right away I said, 'I know he's going to go right back with that pitch.' And sure enough here it was. I hit that one just a little better then I'd hit the other two. And it got into the right-center field bleachers. There's the lucky part right there. He gave the pitch away practically, he gave it away. I assumed that just by his actions, and I was right, and I must have given it a little extra something because that one there did go.

HOF:

Ted, I think you give too much credit to luck and not enough to your perceptiveness.

TW:

Well, you've got to be lucky. I'm going to tell you there's guys that I know had as much ability. I know some that had more ability than I had.

HOF:

It's perception and instinct. It's picking up little things here and picking up little things there.

TW:

Well certainly. To improve, you've got to be observant, you've got to be listening, you've got to experiment. Then you have to decide whether that's good or bad. You keep the good and throw the other stuff away. Most of the outstanding athletes that I've ever met - in boxing, basketball, baseball, football - they may not have been the most well educated guys, but they had instincts.

HOF:

You were inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1966. When did you first think that maybe you had a chance of earning election?

TW:

I never thought of that too much. I was making baseball history, but I never thought of the Hall of Fame. All I wanted was for people to walk down the street and say, 'Boy, that guy was some hitter, he's the best hitter that I ever saw.' I was thinking in terms of that. I was creating some stats, but I didn't even think of about the stats, about the Hall of Fame and all that. Sure, I wanted to lead the league and sure I wanted to hit 35 home runs and sure I wanted to hit .400 if I could but that doesn't happen all the time.

HOF:

Was 1966 your first visit to the Hall of Fame?

TW:

No. Early in my career we played a game in Cooperstown. We played that first year there. It was a small ballpark. I did hit a home run that day. I didn't hit it good, but I did hit a home run. But the thing that I remember was that Dominic DiMaggio was on our team that year. He was a great center fielder. There was a ball hit in the second inning into right center. There were old seats out there on the field, the kind you could take down and set them up again. The seats were maybe three feet high. Dominic ran right into the bleachers and knocked himself down and I thought he was going to kill himself on that play. Well, he was all right but he scared everybody in the ballpark with that job. I could never forget that.

HOF:

What advice would you give to a youngster today, who has aspirations of becoming a good hitter in the Major Leagues?

TW:

He's got to try to read as much as he can about hitting. That's the downfall of most players in baseball. Former President Bush loved to talk about hitting and baseball particularly. He was the captain of the Yale team. He said, 'I was a pretty good fielder, but I had a little trouble hitting.'

A dad takes his kid out, the kid's doing pretty good and all of a sudden he starts to get in a little better league and now he's not hitting like he used to. Finally he doesn't even make the Baseball team. His father might say, 'Let's start playing golf.' So that could be the next step or he might be a tall guy, so he might say, 'Let's try basketball.' That's the downfall of most young Baseball players.

Now hitting's a hard thing to do and some guys can talk to you for a month and a half and they wouldn't teach you one thing about hitting. It's hard to coach and you have to have experience to do it. You've got to have some ability, have good eyes, and you have to have athletic ability where you can swing coordinated and quick. Making good contact with a round ball and a round bat even if you know what's coming is hard to do. That seems to be the one major thing that all young players have difficulty with. Why? It's the hardest thing to do in baseball. Maybe it's the hardest thing to do in sports. So that's the reason baseball is a hard game to play.

This article was reprinted from the 2000 National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum yearbook. For previous issues of the yearbook, contact the Hall of Fame's Museum Shop at 1-888-425-5633. You may also shop online.

Ted Williams (1918-2002) In Memoriam