- Home

- Our Stories

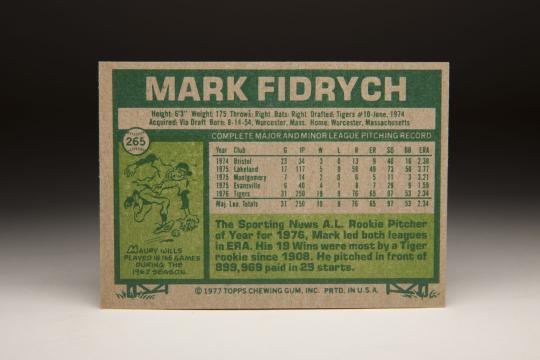

- #CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Mark Fidrych

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

This is the greatest card from 1977.

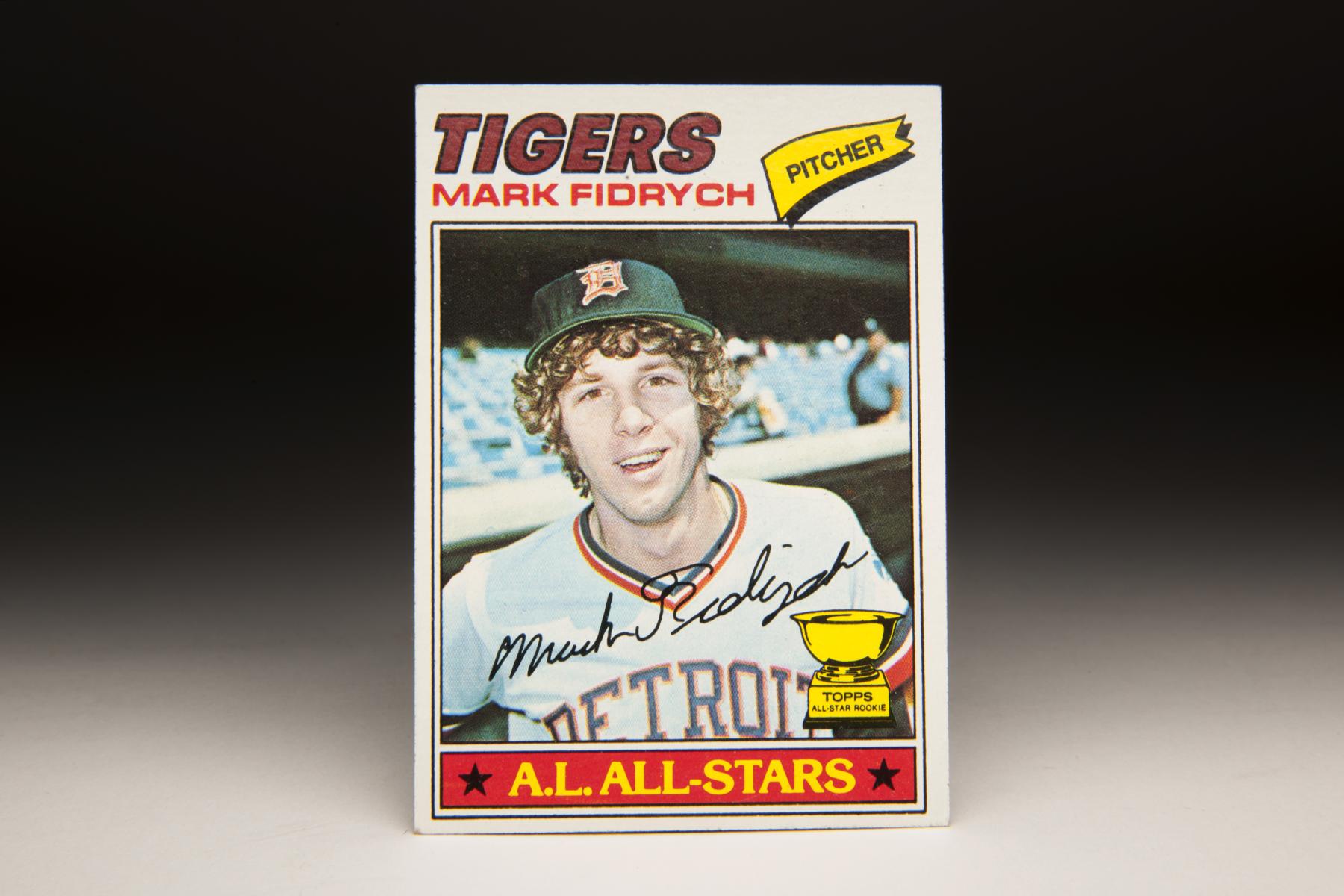

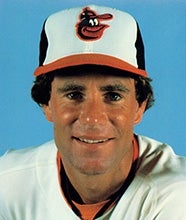

I had waited all year for it. Mark Fidrych. The Bird. It would be better if he were in his home white uniform, but Topps photographers shot as many players as they could in New York City, so here he is, presumably called out for a photo before a game, standing along the visitors’ dugout in Yankee Stadium. But there is so much to love. There is the all-caps “A.L. ALL-STARS” on the bold red banner, a red that shouts, pay attention! Here is someone extraordinary! And there is the huge trophy, the Topps All-Star Rookie Cup, the symbol of early accomplishment.

And of course, Fidrych himself. Those amazing curls that seem to grow from beneath the cap, cascading around his face. And the smile. Not one of those stiff, posed pictures that were so typical of the 1970s Topps cards. No, there is personality here. A naturalness. A lack of pretense. And if it’s not a full smile – the huge, beaming grin Fidrych had as he tipped his cap to the crowds after games – it was a genuine, comfortable, relaxed smile nonetheless. It’s a face that is kind, generous, welcoming. There was nothing artificial about Mark Fidrych.

The season before, he had been a non-roster invitee to the Tigers’ camp, such a long-shot to make the team that the Topps photographer didn’t bother to take a photo of the tall, gangly kid who had already been nicknamed “The Bird” for his resemblance to the Sesame Street character: Tall with curly hair, cheerful and innocent. So there was no Topps card in 1976. Not even a small square shared with other prospects on a “Rookies” card.

But he impressed manager Ralph Houk in Spring Training in 1976 and made the roster. Through mid-May, he only pitched twice, for a total of an inning plus. Then, on May 15, Houk gave him the ball for his first start. It was a drizzly day in Detroit, with a high of 66 degrees. Fidrych had thought of flying his dad in for the game, but he was afraid it would be rained out. Though only 14,583 people attended, the audience was much greater. The Cleveland-Detroit game was the back-up Saturday Game of the Week, and when rains caused delays in Pittsburgh, most of the nation was switched to the Tigers game and the chance to watch Fidrych’s first start.

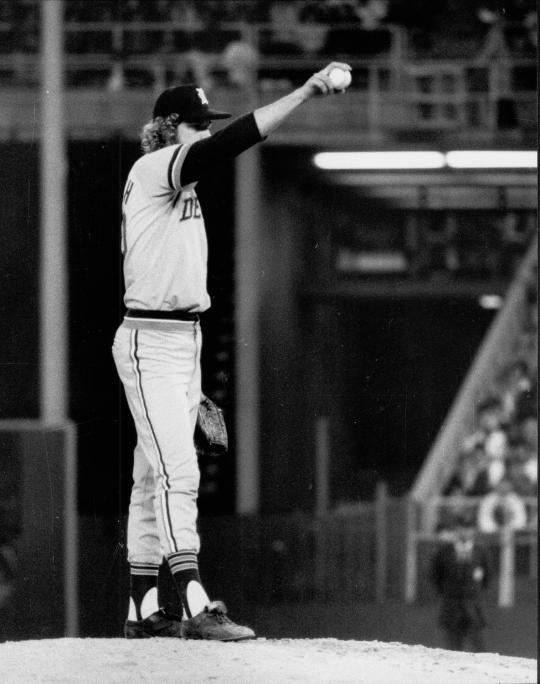

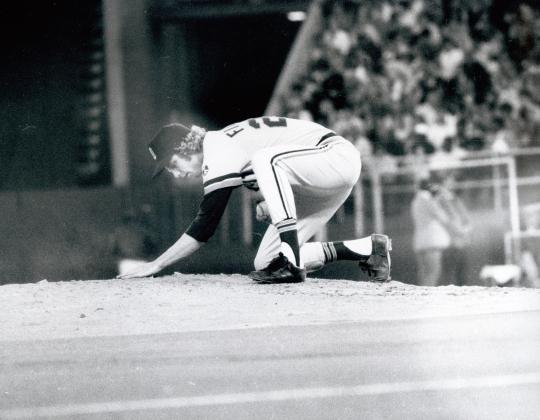

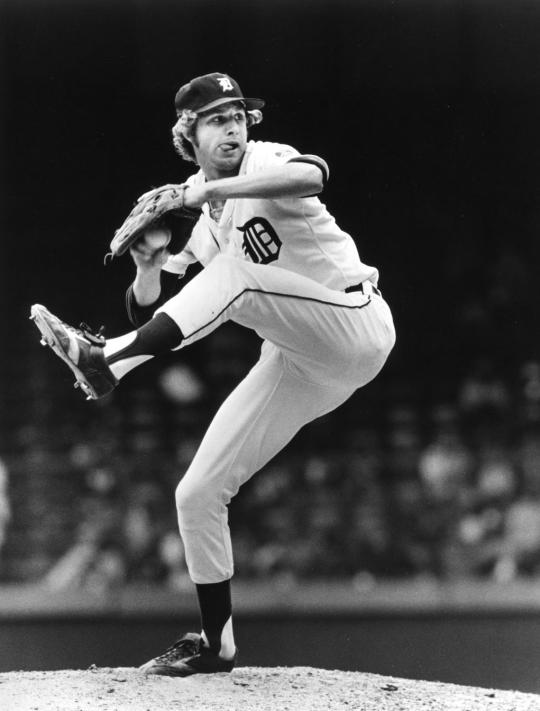

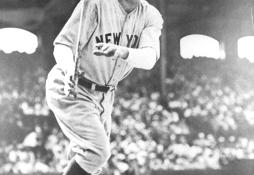

What they saw was unlike anything they had seen before. At the start of the second inning, Fidrych got down on his knees and smoothed out the dirt in front of the mound. There was a reason for it: His dad had taught him to fill in the holes created by the opposing pitcher in the previous inning. When he stood on the rubber and looked in for the sign, he held the ball out in front of him, then moved it back to his body, then out again. And he talked to himself, a constant chatter (the media loved to say he was talking to the ball). Then a long, leggy wind-up and a hard fastball, pounding the bottom of the strike zone. And energy. So much energy. Circling the mound between batters, bobbing up and down, squatting, standing. The Detroit Free Press called him “fidgety” and noted how he “sticks his tongue out of the right corner of his mouth on almost every pitch.”

Fidrych was energy personified, always in motion, moving the ball in and out while on the mound. Photo by Bob Bartosz. Fidrych-Mark-2233-2000_act_NBL-Bartosz (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

But no one could hit him. Literally, through six innings. He finally gave up a leadoff single in the seventh. When the game was over, he had a 2-1 victory, allowing two hits in nine innings. He struck out five, but by keeping the ball low, he induced 16 groundouts.

And that’s how it started. The first of six straight complete games, including two 11-inning contests (he’d go on to lead the American League with 24 complete games). The first of 19 wins. Through July, he only had three losses, in which he gave up a total of four runs, three earned (and had zeros runs of support). It was the beginning of a run – a movement, really, a phenomenon – when he was embraced not only by Detroit, but by fans everywhere. In the summer of 1976, a bicentennial year with red-white-and-blue bunting, no one was bigger than the Bird. Tiger Stadium would fill to bursting when Fidrych pitched, then empty out again for the rest of the week. On the road, crowds would flock to see the Bird.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

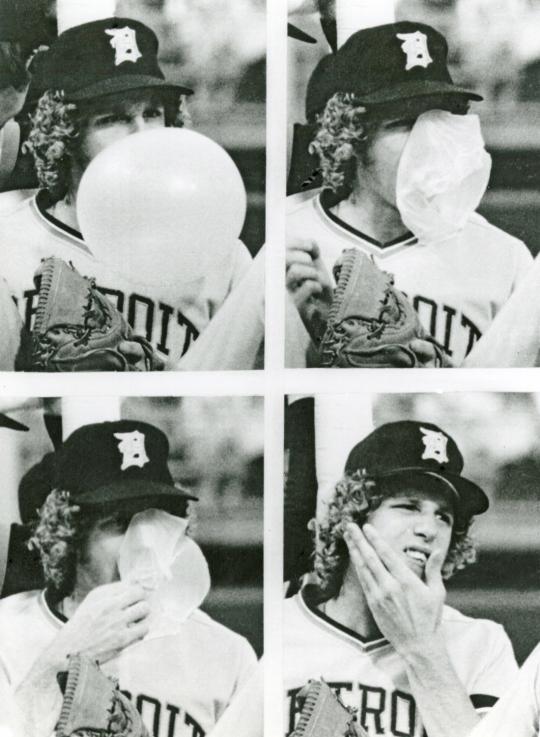

He was pitching brilliantly, but above all, people came to see Fidrych, the phenomenon - the charisma, the energy, the things he did that no one had ever seen before: Grooming the mound, talking to himself, gesturing with the ball, applauding teammates for good plays, patting them on the back, chewing gum and blowing huge bubbles, tugging at his cap, staring in for the sign while moving the ball in and out, in and out.

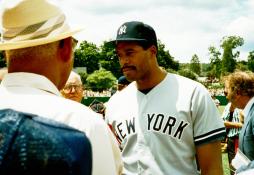

A few players didn’t like it, at least not at first. Yankees catcher Thurman Munson, as opposite in personality as Fidrych as possible, called his antics “bush,” and said Fidrych was “fly-by-night” and a “showboat.” When Fidrych was asked to respond, he replied, “Who’s Thurman Munson?” He preferred playing games to watching and Munson hadn’t been in the lineup, so it was an innocent question, but many took it as a playful rebuttal. Munson himself seems to have taken it that way, going out of his way to extend an olive branch to Fidrych at the All-Star game that July.

On another occasion, Claudell Washington tried to break up Fidrych's energetically fast pace by stepping out of the box repeatedly. Finally, Fidrych stepped off the rubber and squatted, waiting, as if to say, "Take your time; I'll still be here when you're ready." When Washington did finally stand at the plate, Fidrych threw a pitch inside, and Washington took several steps, bat in hand, toward Fidrych, which emptied the benches.

But most players took Fidrych’s behavior in stride, even players not normally known as gracious. About Fidrych’s unusual on-mound behavior, George Scott said, “I like it. That’s confidence. A lot of people call it flaky and a lot of people call it loony, but I like it.” Reggie Jackson: “He’s a very enjoyable person and I look forward to facing him.” Billy Martin: “He does some strange things on the mound, but if they help him win, more power to him.”

In the meantime, fans were enthralled. In pre-ESPN days, most people were only reading about Fidrych, up until his unforgettable Monday Night Baseball debut on June 28, 1976. Everyone had been talking about The Bird. Now the entire nation could finally see this phenomenon in action. 48,000 fans crammed into Tiger Stadium, many with home-made signs or waving iron-on T-shirt stickers that were given away at the gate. Throughout the game they chanted, "Go, Bird, go!"

Fidrych dazzled, giving up one run in nine innings. After the last out (a ground out, one of 14), Fidrych bounced around looking for teammates to congratulate, or groundskeepers, or even a startled security guard. Fans stood and clapped and chanted “We want Bird! We want Bird!” Fidrych, already dressed down, wasn’t one to take the spotlight from his teammates, and said he’d only go out if Rusty Staub (who had provided the offense with a home run and three RBI) went with him; Staub replied that the fans weren’t chanting “We want Staub,” and coaxed Fidrych to go out alone for a curtain call. That would become a pattern throughout the season, which Fidrych eventually got used to, within limits – he didn’t think he should take a curtain call if the Tigers lost, no matter how well he had pitched nor how loud the crowd chanted.

Through all the attention, the hoopa, the mania, Fidrych remained unassuming and authentic. After striking out Hank Aaron, Fidrych said, “Whoa! I struck out Hank Aaron! Here he is, I mean, a superstar, right? And here I am, a little guy, pitchin’ to him.” He had an apartment with almost no furniture and no phone. He said if he wasn’t playing baseball, he’d be working at a gas station, and he meant it, and he was excited about it. He was constantly deflecting credit: “It takes nine other guys to win, not just me. Hey, did you see some of the defense they gave me. . . . Hey, they are making me.” The handshakes and hugs to his teammates expressed genuine gratitude.

His enthusiasm was infectious. Minnesota manager Gene Mauch said, “I’m honestly more impressed with his enthusiasm than his pitching. That kid might be the best thing that’s happened to this game in a long time.”

And Fidrych seemed to be enjoying the whole ride: “I haven’t woke up yet,” he said. ‘I’m just loving it. I’m just loving it.”

Fidrych continued to win. Eight straight through June. He started the All-Star game. On July 16, he pitched a complete game, 11-inning, 1-0 shutout, and at one point retired 16 batters in a row, 14 on ground balls. He pitched five extra-inning complete games that summer. After a few losses in late August and early September, when many thought he was starting to fade, Fidrych closed the season with four wins in his last five starts, including two shutouts.

But more than that, he was a sensation. A media darling. A fan favorite. The talk of baseball. The star of the Summer of ‘76.

The rest has been well-chronicled. The knee injury, the torn rotator cuff, one painful comeback attempt after another. The later Topps cards of Fidrych carry a tinge of sadness, of “what if?”

Then he died, much too soon, in an accident at his farm when he was just 54 years old.

But focusing on those things misses the point. Because Mark Fidrych was enthusiasm and optimism, humility and happiness. Even after he left the game, he maintained a boyish innocence and authenticity. He embodied wide-eyed wonder at being able to play baseball, and complete joy, captured in that first baseball card, much anticipated by fans, with that bold red All-Star label and all those curls and that smile that says, “I haven’t woke up yet. I’m just lovin’ it.”

Larry Brunt was the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visit www.baseballhall.org/DAP