He has been some kind of ballplayer for us. He has saved us time after time with big hits that either won the game for us or put us in position to win… And he does more than hit. He’s the most solid outfielder I have defensively.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

The year of 2016 has been a tough one in the category of celebrity deaths. We’ve lost many, many stars from the worlds of Hollywood, music, politics and sports. It seems like hardly a day goes by without hearing of the death of yet another notable figure, everyone from Muhammad Ali to John Glenn to Gene Wilder.

Baseball has not been spared either. Over the past calendar year, we have lost one of our oldest living Hall of Famers, Monte Irvin, who provided a link to the glory days of the Negro Leagues. Joe Garagiola, the winner of the Hall of Fame’s Buck O’Neil Award and a contributor as a ballplayer, broadcaster, funny man, and general ambassador for the game, died in March.

We also lost Ralph Branca, the ex-Brooklyn Dodgers great who came to embody the concept of losing with dignity and honor. Walt “No Neck” Williams, the subject of one of our earliest Card Corners, died last January. Slugging Jim Ray Hart, whom we paid tribute to in this same space, passed away in May. So did Dick McAuliffe, the owner of one of the game’s oddest batting stances and a beloved member of the 1968 world champion Detroit Tigers.

There have been others, too. The versatile Tony Phillips. Two hundred-and-nine game winner Milt Pappas. The wonderfully named Putsy Caballero and Choo Choo Coleman. Former San Diego Padre Steve Arlin, grandson of Harold Arlin, who announced the first game ever broadcast on radio. And who will ever forget where they were when the heard the news that one of the game’s current superstars, Jose Fernandez, had died in a horrific boating accident?

In putting together the final Card Corner for 2016, it seems fitting to pay homage to one of the many ballplayers we lost. That he once played for the Chicago Cubs, this year’s world champions, makes it more appropriate. He was also part of the original New York Mets, a team beloved not for winning, but for losing with flair and fun, if such a thing is possible. Along the way, this man made some news on other fronts, both in the All-Star Game and in terms of his relationship with a Hall of Fame manager.

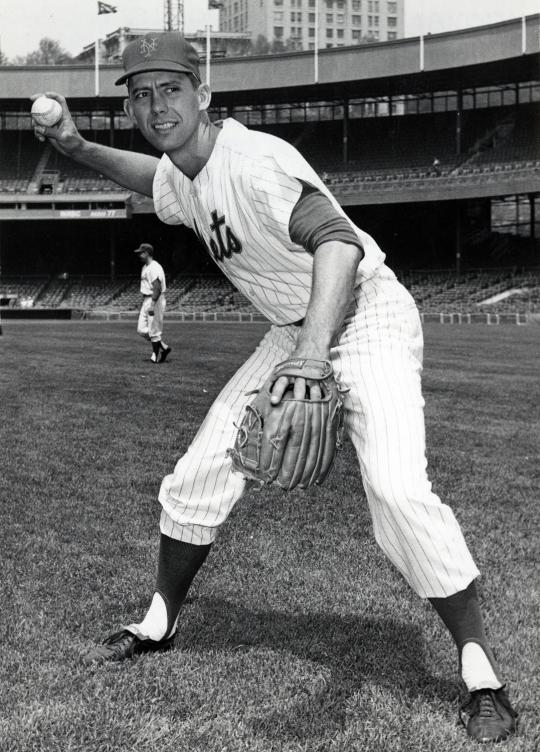

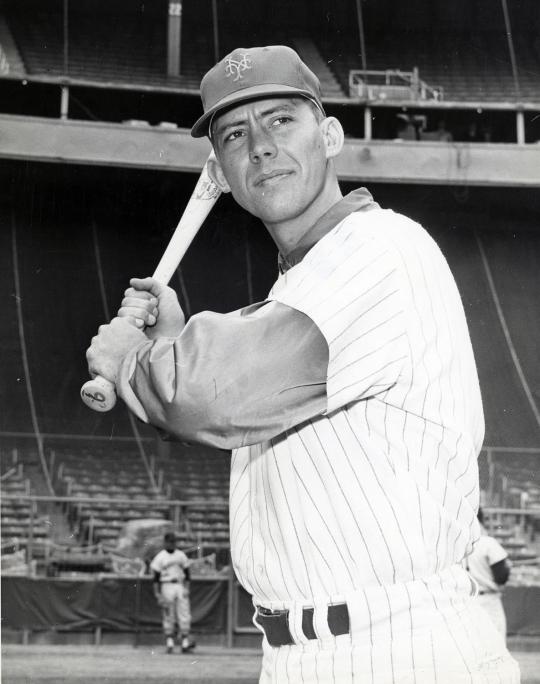

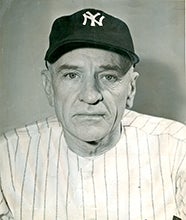

Jim Hickman's first season in the majors was also the New York Mets’ first season as a team, in 1962. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Jim Hickman died on June 25 at the age of 79. His death was not unexpected; he had been in hospice care during his final days. The news of his passing generated a few headlines, but perhaps not as many as it should.

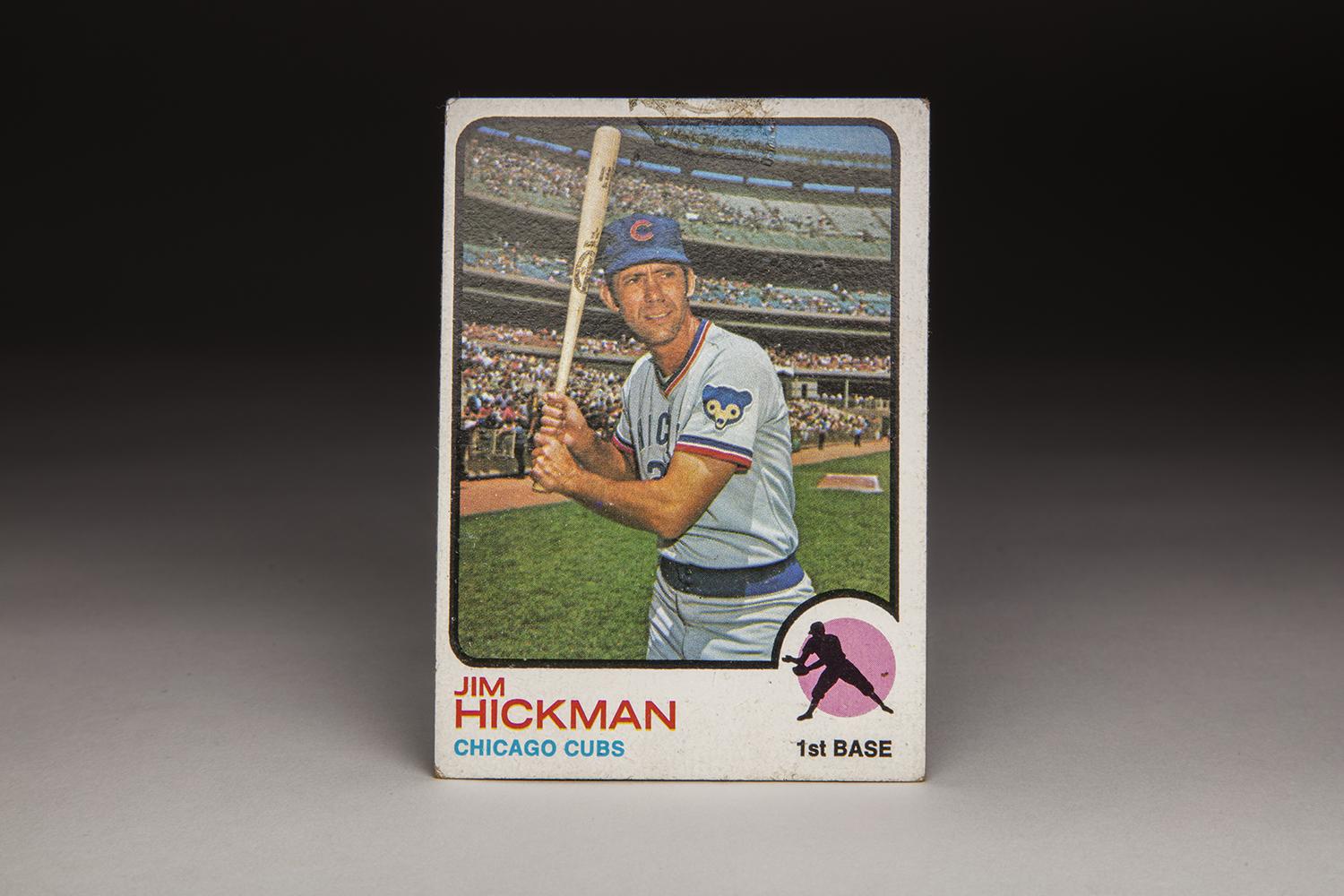

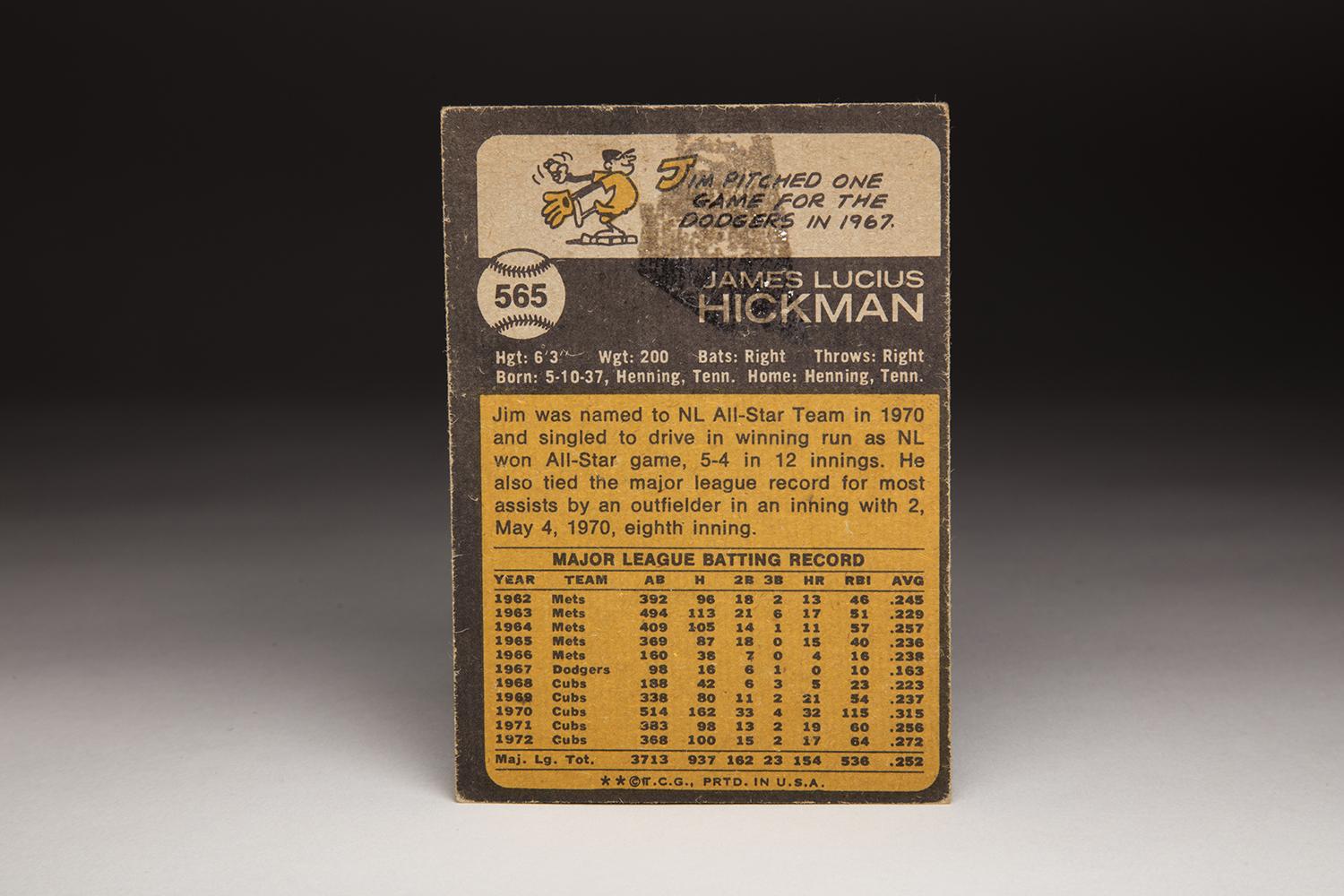

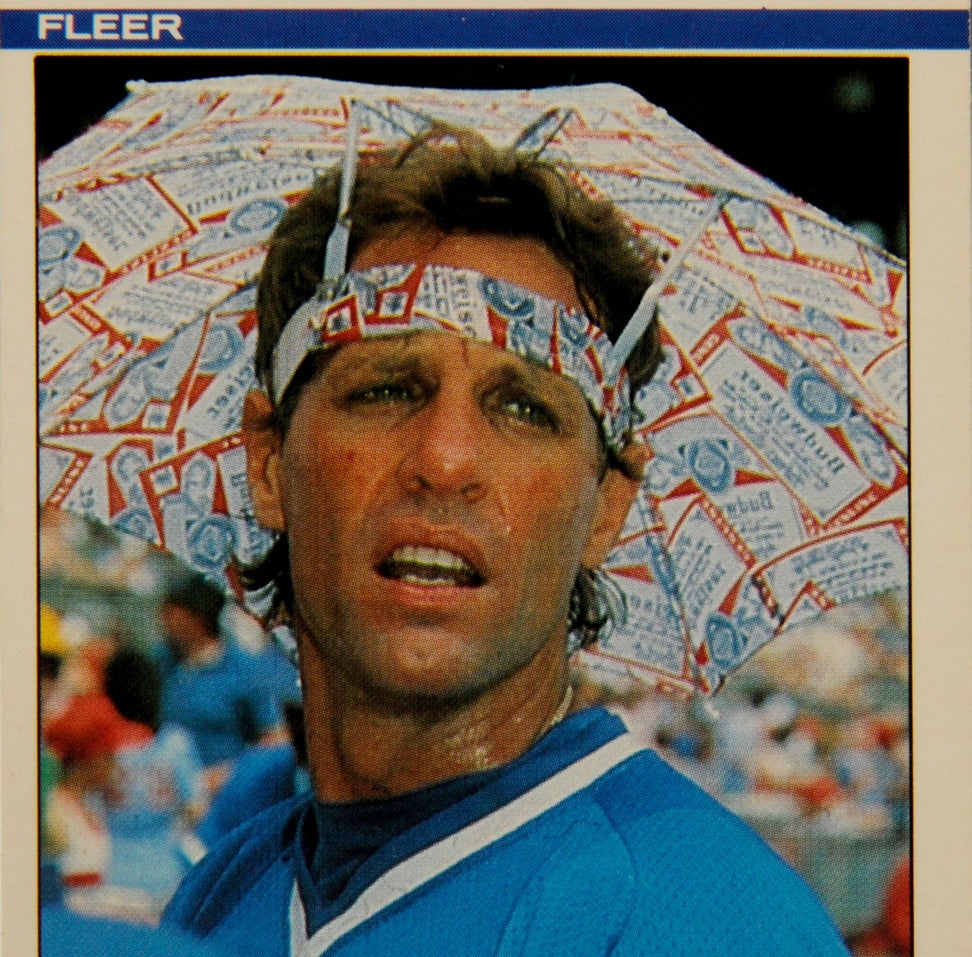

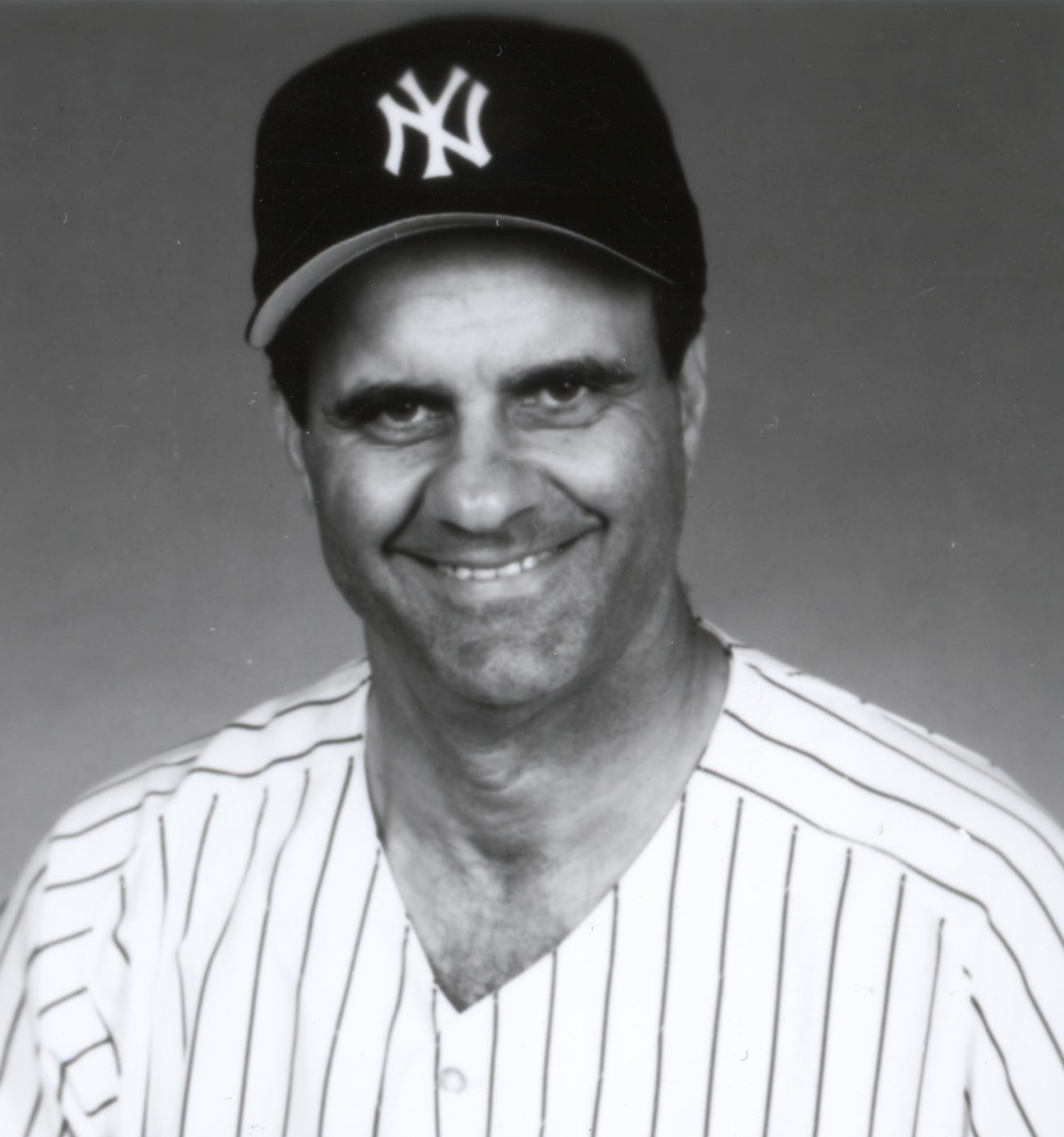

Hickman’s 1973 Topps card, shown here, turned out to be the last card of his career. Like all of the 1973 cards, it has a simple design, a very basic black frame outline and that memorable position silhouette, colored in pink, in the lower right-hand corner. Hickman played both first base and the outfield, but Topps had to pick one, choosing first base for the front of the card.

As with the design of the card, the photograph of Hickman is a simple one. We see him offering up a typical Topps pose, taking his stance with bat in hands, his eyes peering to the left, on a sunny afternoon at Shea Stadium. Yet a closer look at Hickman’s road uniform gives us a glimpse into a changing era in baseball fashions. The Cubs, like every team in the major leagues, had just switched from flannel to polyester uniforms, but had retained the basic gray color for their road jerseys and pants. The Cubs’ baby bear logo is quite evident on the left sleeve, with blue and red piping just below it, marking the end of the sleeve.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of Hickman’s Cubs uniform is the wide, blue, elastic waistband, which replaced the traditional belt and loops that the team had used with its old flannels. A lot of the Cubs’ players, particularly those who were overweight, hated the elastic band because it accentuated their mid-sections. But with Hickman, who was always known for being tall, lean, and fit, the waistband does not look out of place. At six feet, three inches tall and 190 pounds, Hickman looked good in any uniform.

Long before he donned the colors of the Cubs, Hickman signed with the St. Louis Cardinals. Beginning in 1956, he would spend the next six seasons toiling in the St. Louis farm system, unable to crack the Redbirds roster. Some within the Cardinals’ organization felt he had the potential to become the team’s next center fielder, but he found himself blocked by Curt Flood, a Gold Glove performer at the position. Then came the break that Hickman needed: Expansion. In October of 1961, the newly formed Mets began assembling their team through the expansion draft. With the 36th pick overall, the Mets selected Hickman at a cost of only $50,000.

As a southerner from Tennessee, Hickman had hoped to be drafted by the Houston Colt .45s, but at least the Mets offered him an avenue to the big leagues. Though he opened the season on the bench, Hickman soon moved into the starting lineup. He split his time between center field (which he played adequately despite a lack of speed), right field (a better fit given his strong arm), and third base (where he was less comfortable). On a team lacking in young talent, Hickman became the Mets’ top prospect. He batted .245 with 13 home runs and 47 walks. While they were not eye-popping numbers, they stood out on a team that struggled to score runs.

Like most of the Mets’ players, Hickman was overshadowed by his manager, Casey Stengel. The personalities of Hickman and Stengel could not have been more different. While Stengel loved to banter with the press, to the point that he held rambling press gatherings that often left writers in hysterics, Hickman took a quiet, reserved approach. His idea of making a speech was saying, “Thank you.” In some ways, he was the typical southern gentleman, earning himself the nickname, “Gentleman Jim.”

In his second season in New York, Hickman showed more power, with 17 home runs, but the rest of his offensive game slipped. His batting average fell to .229 and his strikeouts rose to 120, which was considered an exorbitant total for the era. The next two seasons produced eerily similar numbers, frustrating the Mets, who had come to expect more from one of their original players. At times, Stengel platooned Hickman, using him only against left-handed pitching. Hickman bristled at the platoon arrangement, feeling that it hindered his development as a hitter.

After the 1966 season, in which Hickman missed significant time with a wrist injury, the Mets saw a chance to acquire two-time batting champion Tommy Davis from the Los Angeles Dodgers. So they sent Hickman and scrap-iron infielder Ron Hunt to LA for Davis and backup outfielder Derrell Griffith.

Hickman’s lone season in Los Angeles turned into a fright fest. He didn’t hit, losing any chance of taking an outfield job from either Lou Johnson in left field or Ron Fairly in right field. By season’s end, he had appeared in only 65 games and put up a batting average of .163. Remarkably, he did not hit a single home run.

To make matters worse, Hickman developed an ulcer during the season. A quiet sort who kept his feelings and his opinions to himself, Hickman internalized his struggles, perhaps contributing to the ulcer. The malady forced him to switch to a liquid diet for a while. He also began to take Maalox, which he kept in his clubhouse locker for the rest of his career.

At one point, the Dodgers demoted Hickman, sending him back to the minor leagues, where he had not played since 1961. In an interview with Woodrow Paige of the Sporting News, Hickman admitted that he nearly quit the game. “Los Angeles sent me down to Spokane, and I was really dejected…So I went to Spring Training late.”

That decision did not endear him to Dodgers’ management. He was scheduled to start the 1968 season at Triple-A Spokane, but on Opening Day, he was called into the manager’s office. The Triple-A manager, who happened to be Tommy Lasorda, told Hickman that he would be reporting immediately to Tacoma, the Triple-A affiliate of the Cubs. The parent Dodgers had just traded him and relief pitcher Phil Regan to the Cubs for outfielder Ted Savage.

Hickman again thought about quitting, but the deal turned out to be just the break that he needed. In May, the Cubs brought him up to Chicago, giving him the chance to play for a new manager in Leo Durocher. Durocher used Hickman as a platoon player in 1968, but eventually moved him into the starting lineup in August of 1969. As the regular right fielder, Hickman found his power stroke, hitting 21 home runs and slugging .467 for the season. His batting average still lagged at .247, but a willingness to take the occasional walk raised his on-base percentage near .330.

As the Cubs collapsed down the stretch, allowing their eight-and-a-half game lead over the Mets to fritter away, Hickman was one of the few players who continued to perform. “He has been some kind of ballplayer for us,” Durocher told Chicago sportswriter Edgar Munzel. “He has saved us time after time with big hits that either won the game for us or put us in position to win… And he does more than hit. He’s the most solid outfielder I have defensively.”

Unfortunately, Hickman alone could not prevent the Cubs from completely squandering the Eastern Division title. Many of the team’s regular hitters slumped in August and September, perhaps because of fatigue and perhaps because they felt worn down by the hot and humid Chicago summer. After the season, Durocher made a point of praising Hickman for his continued fine play amidst the chaos of a team-wide collapse.

For the rest of his life, Hickman credited Durocher as the man who turned his career around, simply by giving him the opportunity. “I always felt I could hit,” Hickman told Sports Today in 1971, “but it wasn’t until I got to Chicago that I had a chance to play every single day… I admire the man [Durocher]. He gave me a chance to play. With him, you know you’re going to get that chance. Then you have to produce.”

Hickman did just that in 1970. Though Hickman was now 32 years old, he assembled a season for the ages. He reached career highs in every category: a .315 batting average, 32 home runs, 115 RBIs, and on-base percentage of .419 and an OPS of over 1.000. He placed eighth in the MVP voting. As a bonus, the Sporting News named him the National League’s Comeback Player of the Year.

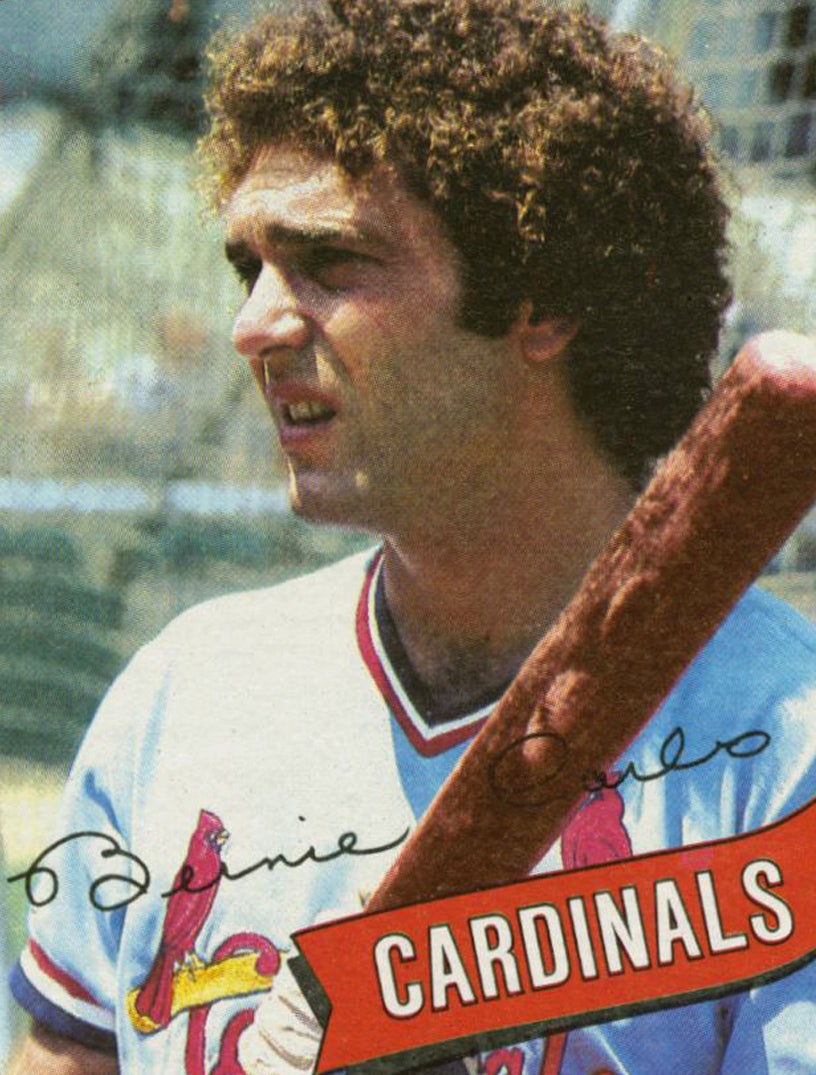

With his legs spread wide in the batter’s box, Hickman’s batting style reminded some of two Hall of Famers from past generations. “Scouts tell me that Hickman has the same open stance that both [Rogers] Hornsby and [Joe] DiMaggio used,” said Joe Torre, at the time a star third baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals. “That way, Jim is over the plate and in good position to make solid contact with any pitch in the strike zone. He plays long ball with a short swing and isn’t fooled too often.”

Earning selection to his first and only All-Star Game, Hickman received some national notoriety, but in an indirect way. In the 12th inning of the Midsummer Classic, Hickman smacked a line single toward center field. National League teammate Pete Rose rounded third and headed for home, where he violently collided with American League catcher Ray Fosse. Not only did Rose score the winning run, but the fierce collision became an iconic moment in All-Star Game history, leaving Fosse with an injured shoulder and rendering him a shell of the promising player he had been.

Over the next two seasons, Hickman sustained nagging injuries and illnesses (including a bleeding ulcer) that limited him to under 120 games each summer. Still, he remained productive when he played. He hit 36 home runs over the two-year stretch and walked nearly as often as he struck out.

In 1973, Hickman started to show the inevitable signs of age. Limited to 92 games, he hit only three home runs and slugged a paltry .313. He lost playing time to two other first basemen, young Pat Bourque and veteran Joe Pepitone.

Even though the Cubs retained him over the winter, Topps rather curiously did not produce a card for Hickman in 1974. Perhaps the card company knew something was up. In the spring, the Cubs dealt Hickman to his original organization, the Cardinals, for hard-throwing right-hander Scipio Spinks. Hickman finally appeared in a Cardinals uniform, something that had eluded him at the start of his career, and hit decently in a backup role. But the Cardinals had an overcrowded outfield, and the numbers game resulted in him becoming the odd man out. On July 16, the Cardinals cut loose the veteran first baseman, ending his career at the age of 37.

Hickman took the news without bitterness. He also announced that he had no interest in signing with another team, even though it’s possible a contending club would have liked to bring him on. Instead, Hickman simply left the game and returned to Henning, Tenn., to be with his wife and four children and tend to his sprawling 650-acre farm.

Other than a short stint with the Cincinnati Reds’ organization as a hitting instructor, Hickman remained out of baseball. He preferred to concentrate his efforts on his farm, which specialized in the growing of cotton and soybeans. It’s something that he continued to do until his retirement.

Just as Hickman spoke quietly during his major league career, he lived quietly away from the ballpark. Perhaps that’s why his death this past summer came without much attention. But Jim Hickman deserves a little bit more. A

good ballplayer and a fine family man, Gentleman Jim made a name for himself. The game will miss him.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame