- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Reggie Jackson

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Reggie Jackson

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Forty-five years ago, the Oakland A’s’ Spring Training camp in Arizona became the site of a minor kerfuffle. In retrospect, it’s hard to believe that the situation caused even the smallest of blowups.

In today’s day and age, no one would care if a major league player reported to spring camp wearing a mustache. Oh, it might cause some amusement, but certainly no conflict or controversy. But in 1972, within the very conservative establishment of baseball, that was something that just was not done very often. Once the “controversy” began, it could only conclude with the staging of one of the most unusual promotions in the history of our great game.

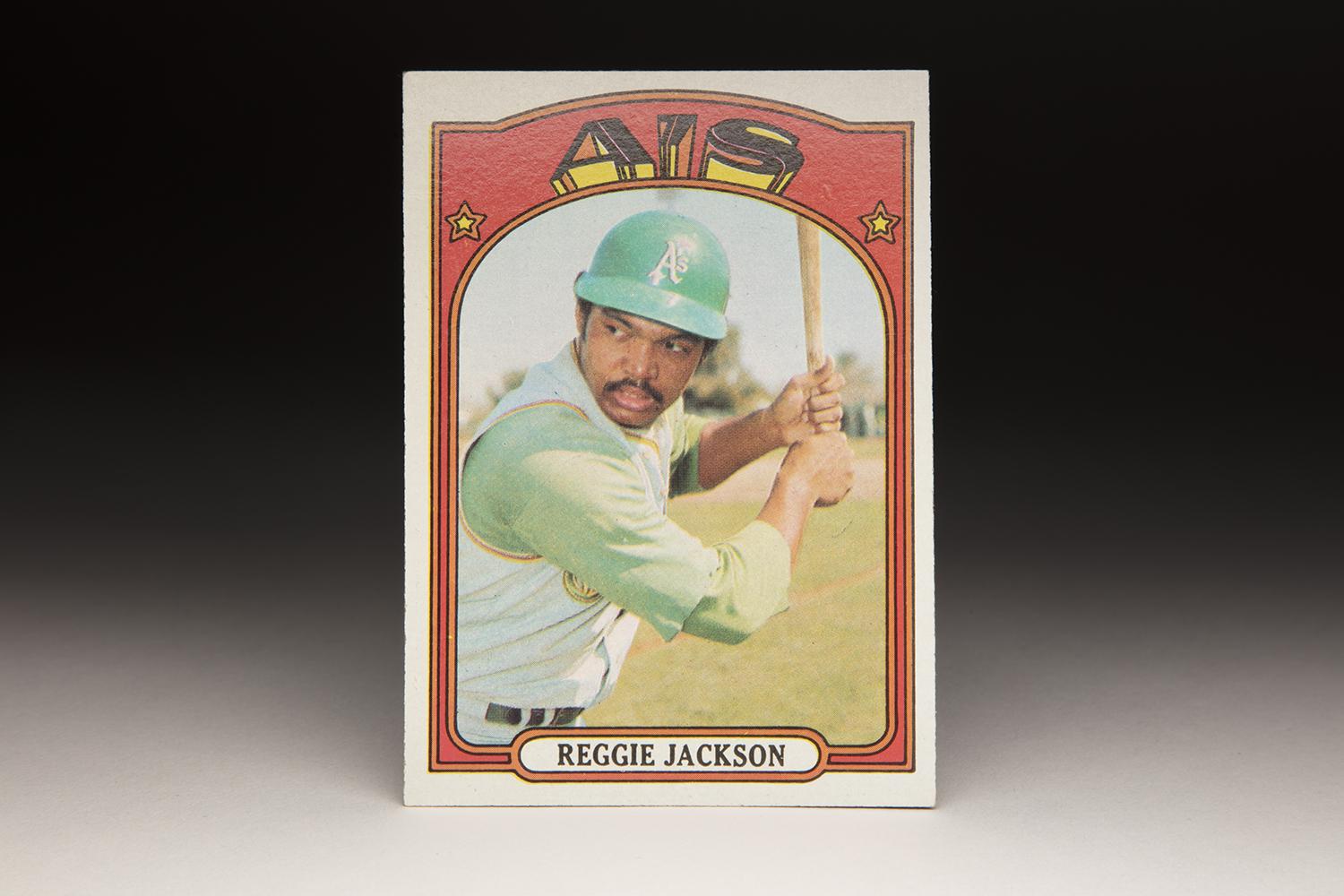

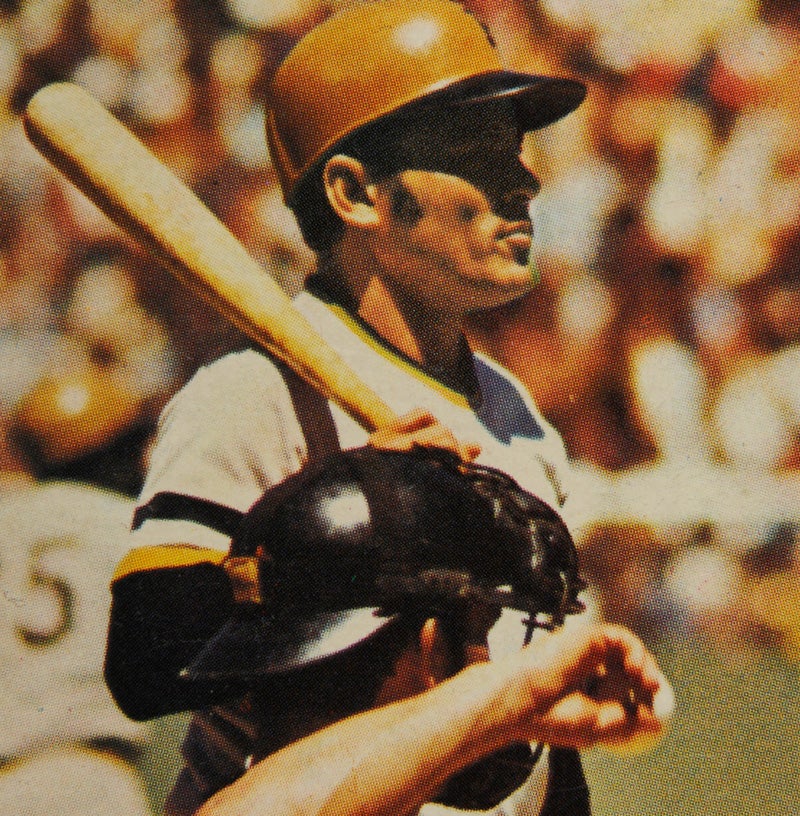

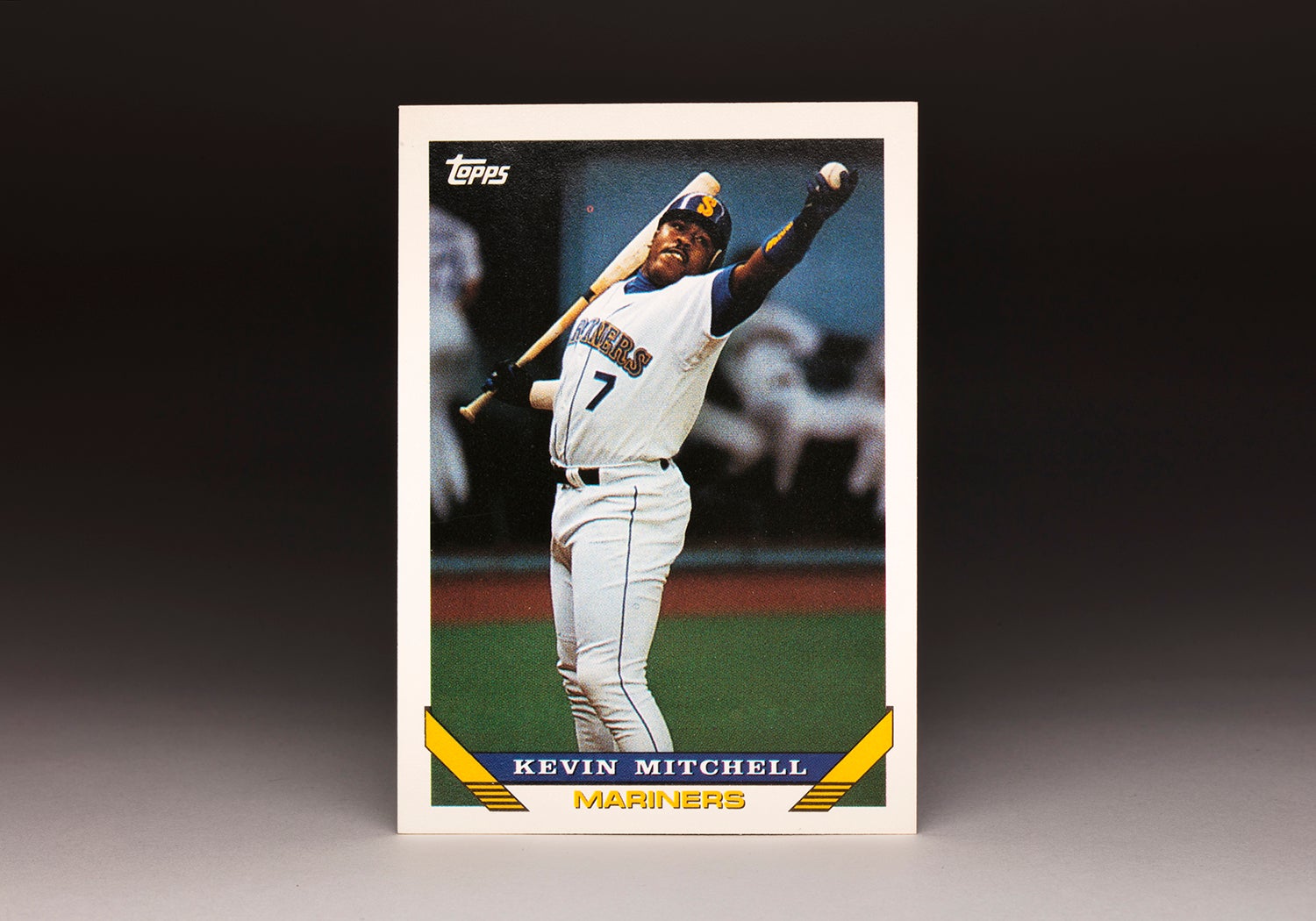

So what exactly happened? A look at Reggie Jackson’s 1972 Topps card tells a good part of the story. Notice that Jackson is sporting a fully grown mustache in the photograph, a rarity for players of that era. The mustache is actually an indicator that the photo was not taken during the previous season of 1971, but rather during Spring Training of 1972. How do we know that? Jackson did not have a mustache during the 1971 regular season; he started sporting a full mustache in the spring of ‘72.

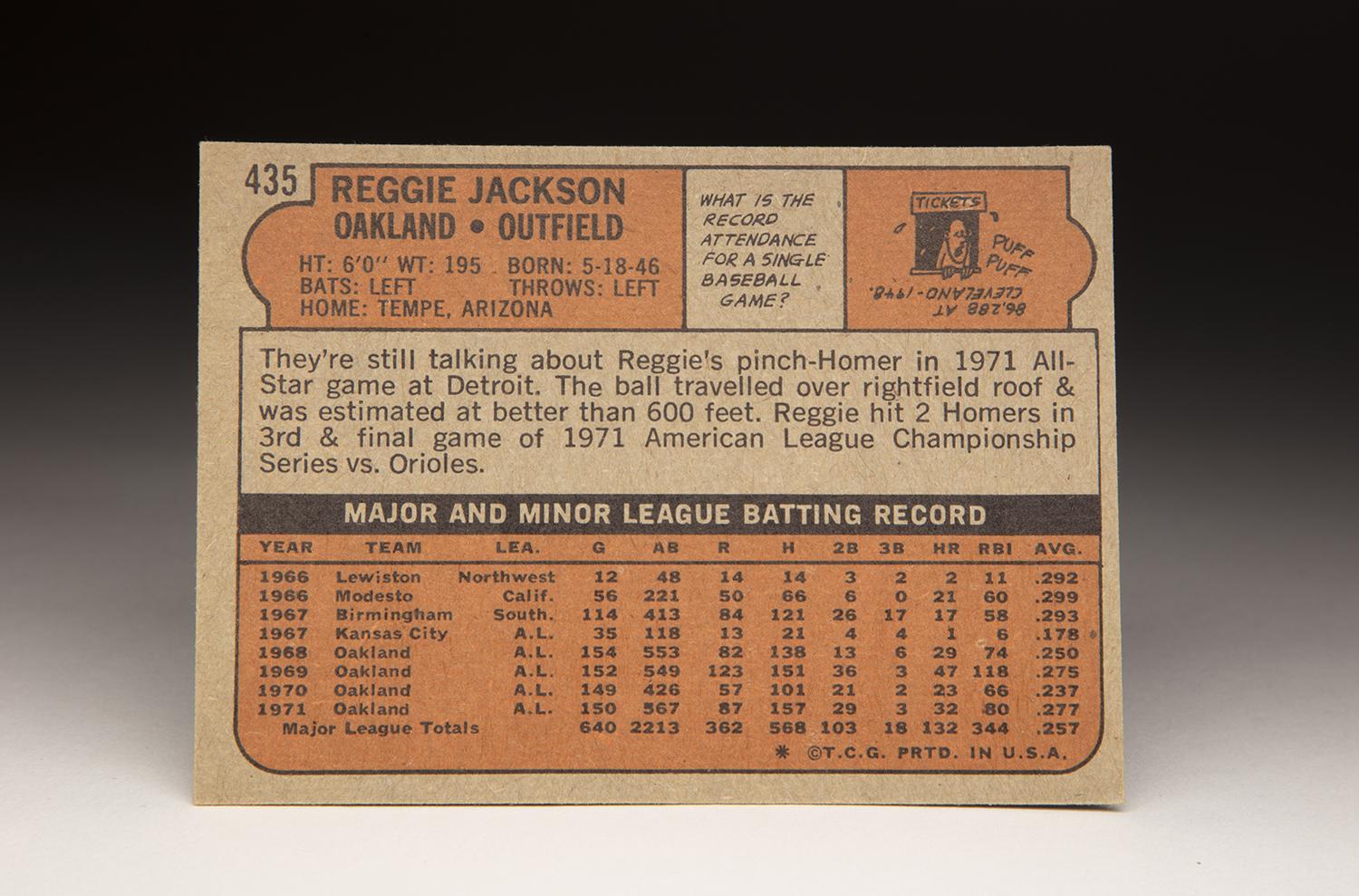

The Jackson card, No. 435 in the set and part of the Topps’ high-numbered series, came out several months after the initial series, and well into the 1972 season. Due to the lateness of the card’s release, Topps was able to use a photograph of Jackson from that spring. So this is one of those rare occasions where Topps used an updated, current year photograph to depict a player in one of its sets.

In showing up to training camp in March of ’72, Jackson made major news by sporting his mustache. (He had actually started growing the mustache during the 1971 playoffs against the Baltimore Orioles.) To the surprise of his teammates, Jackson had allowed the mustache to reach full bloom during the winter. In addition, Jackson told his teammates that he might also grow a beard by the time that Opening Day rolled around.

In today’s game, where players wear mustaches, beards of various kinds of lengths, long sideburns, Mohawk haircuts, dreadlocks, hair down to the collars and large Afros, a mustache would hardly create a ripple. Other than the New York Yankees, who do not permit beards or long hair, every team allows facial hair. But in 1972, baseball remained a conservative bastion within a culture that had become very rebellious.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Young men throughout America tended to wear mustaches, beards and long hair; it was a common thing to do, particularly within the so-called hippie counter-culture movement. But within baseball, no one sported a beard. Few players had hair that reached their shirt collars, and there were no players who were growing mustaches.

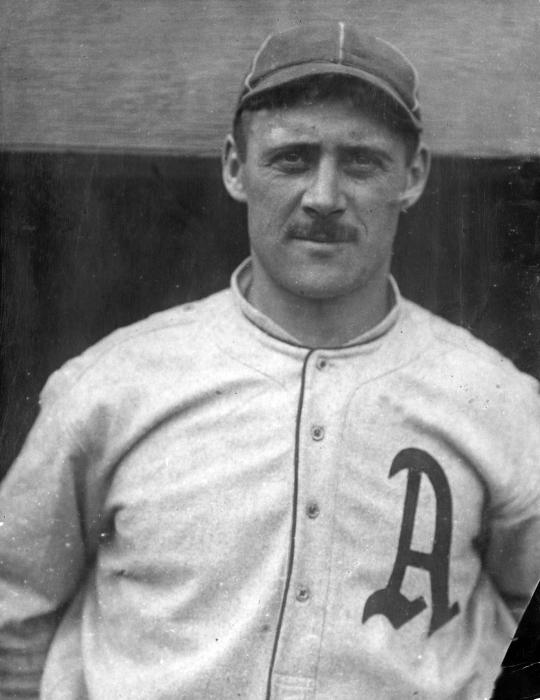

From 1914 to 1970, mustaches were unofficially barred from the major leagues. There was no official rule, but merely an unofficial one, a gentleman’s agreement, if you will. In 1914, Wally Schang of the Philadelphia A’s had sported a mustache. And then nothing, at least not until Richie Allen showed up to camp in 1970 with a mustache of his own.

In the post-Schang era, a few players had donned mustaches during Spring Training. The short list included including Stanley “Frenchy” Bordagaray, a colorful outfielder from the 1930s and forties. One spring, Frenchy showed up to camp with facial hair, but he was ordered to shave the mustache by Opening Day. In those days, players did as management told. In 1970, Clete Boyer reported to the Atlanta Braves’ spring camp wearing a mustache, but he also rid himself of the undesired facial hair by Opening Day.

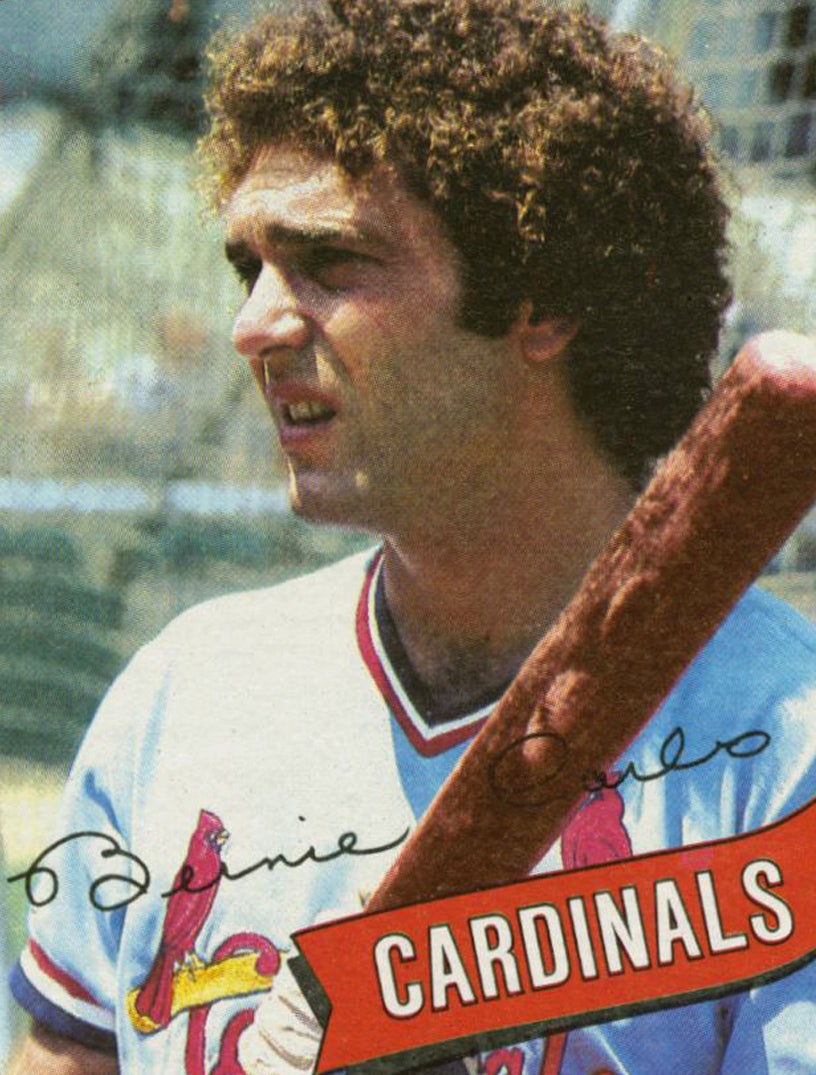

As longtime SABR member and researcher extraordinaire Maxwell Kates once learned, Richie Allen (as he was known at the time) broke the hairless streak by wearing a mustache with the St. Louis Cardinals during the 1970 season. In fact, Allen’s 1971 Topps card, which was photographed after he was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers, shows a mustache in clear view. For some reason, the story never gained much traction, perhaps because Cardinals management expressed little opposition to Allen’s latest act of rebellion.

The situation with the 1972 A’s became an entirely different matter. Those A’s happened to be owned by Charlie Finley, a magnet for controversy and confrontation. Not surprisingly, Jackson’s mustachioed look cornered the attention of Finley and his manager, Dick Williams. Several years ago, former A’s first baseman Mike Hegan, who has since passed away, provided me with the details of what happened that spring.

“The story as I remember it,” said Hegan, “was that Reggie came into Spring Training with a mustache, and Charlie didn’t like it. So he told Dick [Williams] to tell Reggie to shave it off. And Dick told Reggie to shave it off, and Reggie told Dick what to do.

“This got to be a real sticking point, and so I guess Charlie and Dick had a meeting, and they said well, ‘Reggie’s an individual so maybe we can try some reverse psychology here.’ Charlie told a couple of other guys, I don’t know whether it was [Dave] Duncan, or Sal [Bando], or a few other guys to start growing a mustache. Then, [Finley figured that if] a couple of other guys did it, Reggie would shave his off, and you know, everything would be OK.”

According to Sal Bando, the captain of the A’s, Finley wanted to avoid having a direct confrontation with Jackson over the mustache. For one of the few times in his tenure as the A’s owner, Finley showed a preference for a more indirect approach. “Finley, to my knowledge,” Bando said, “did not want to go tell Reggie to shave it.”

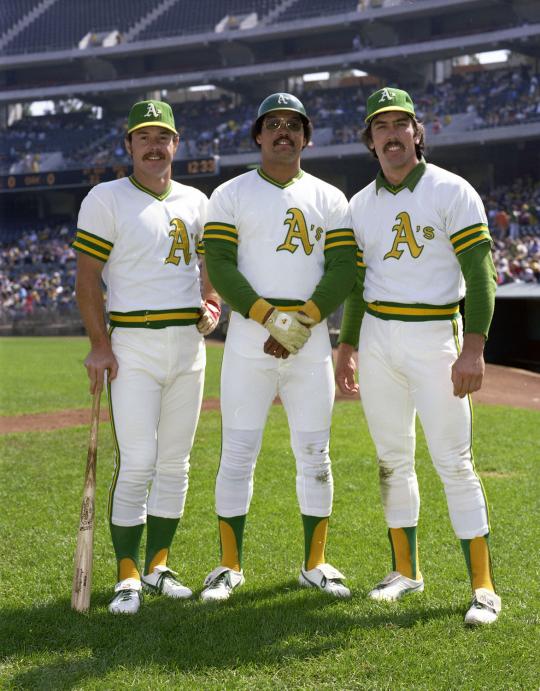

Instead, Finley devised an alternate plan. “He thought it would be better to have all of us grow mustaches,” Bando explained. “That way, Reggie wouldn’t [stand out as] an ‘individual’ [anymore].” Several other Oakland players picked up on Finley’s plan, and decided to grow mustaches themselves. Jim “Catfish Hunter, Darold Knowles, Bob Locker, and Rollie Fingers, all veteran pitchers, sprouted their own mustaches.

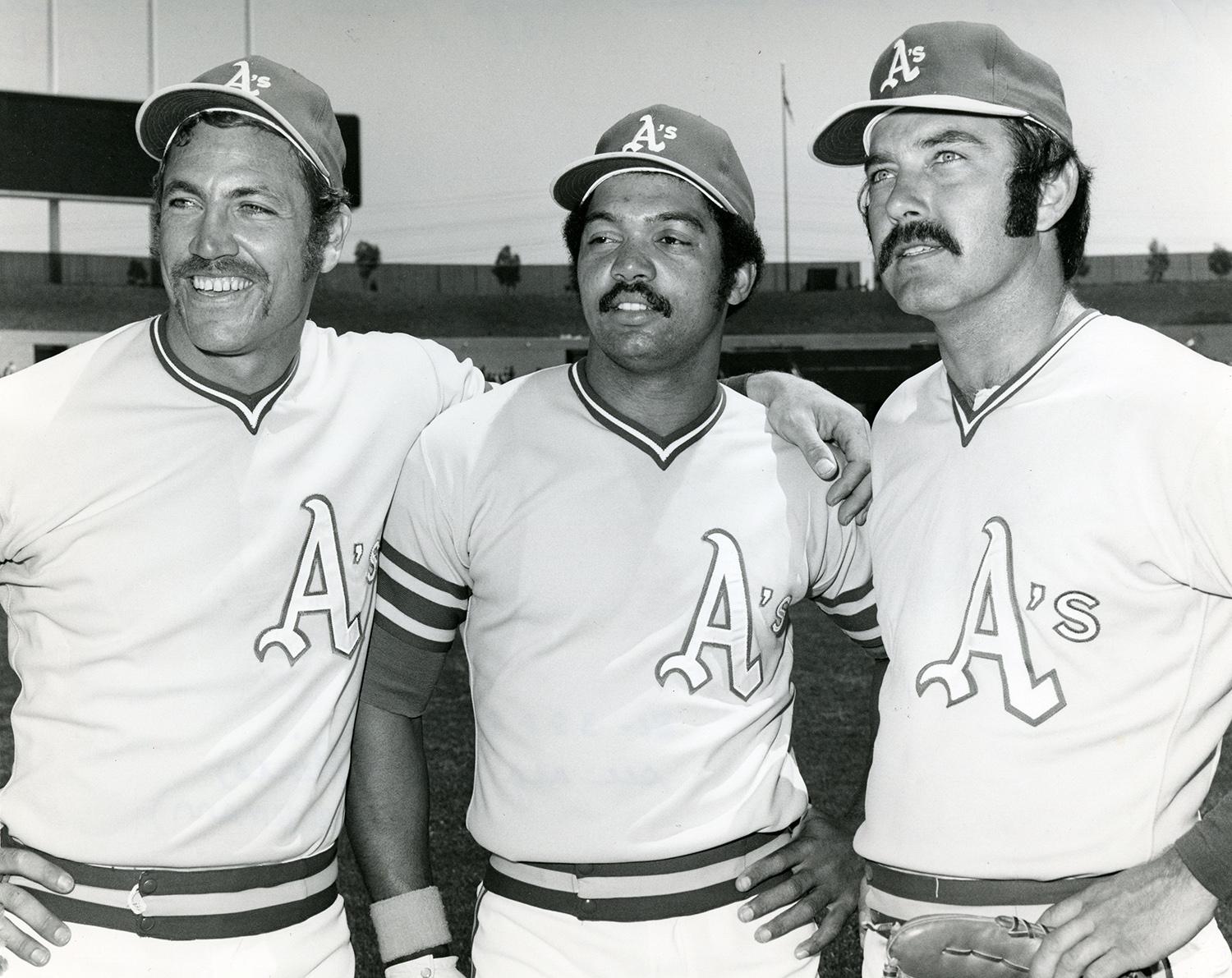

Finley had hoped that once the other players grew facial hair, Jackson would get rid of his mustache. Instead, the opposite happened. “Well, as it turned out, guys started growing ‘em, and Charlie began to like it,” says Hegan in recalling the origins of baseball’s “Mustache Gang.” “So then we all had to grow mustaches,” says Hegan, “and that’s how all that started. By the time we got to the [regular] season, almost everybody had mustaches.”

Even manager Dick Williams, known for his military haircut and clean-shaven face during his days as the skipper of the Boston Red Sox, joined the brigade by growing a patchy mustache of his own. This was an especially surprising development, given Williams’ preference for the old-school way of doing things.

Yet, the story does not end there. Now that many of the Oakland players had developed the shaggy look, Finley realized that he could capitalize on the situation. In May, the owner called an offbeat press conference to announce that the A’s would hold a special promotion on Father’s Day, which fell on June 18. For the first time ever, “Mustache Day” would take place at the Oakland Coliseum. As part of the promotion, Finley promised to pay $300 bonuses to any player who grew a full mustache by Father’s Day. In addition, all mustache-bearing fans would receive free admission to the Coliseum.

Initially, three players expressed a lack of interest in taking part. They were Bando, Hegan, and utility infielder Larry Brown. So Finley called the three players into his office and gently convinced them to follow the program. Reluctantly, the three players agreed.

All 25 players on the active roster, Bando and Brown and Hegan included, sported mustaches by Father’s Day. The A’s then proceeded to club the Cleveland Indians, winning 9-0, behind Vida Blue’s two-hit shutout. After the game, Finley fulfilled his promise of a cash reward. “At the end of the game, there was a couple of hundred bucks in everybody’s valuable box,” confirmed Hegan. “[There was also] a little thank-you note for growing the mustaches.”

At the cost of $7,500, Finley had put together a successful promotion, forever cementing the image of the ’72 A’s as the “Mustache Gang.”

Wally Schang sported a mustache in 1914 while playing for the Philadelphia Athletics, but facial hair was largely frowned upon in the big leagues from the early 20th century until the 1970s. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

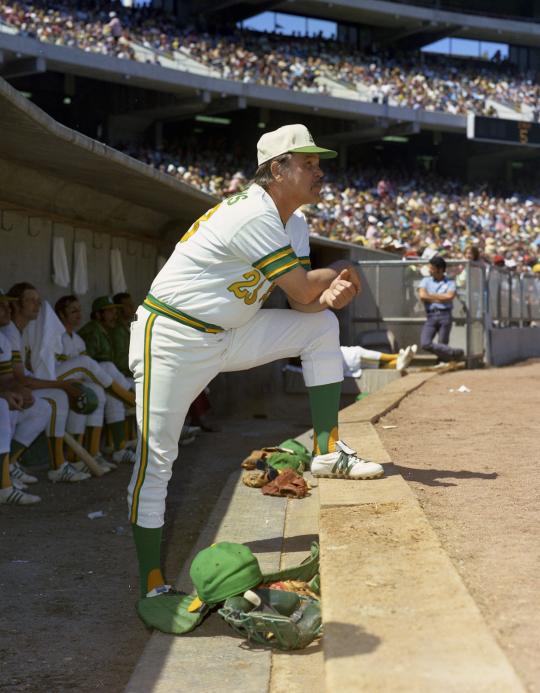

Though Athletics manager Dick Williams was was known for his clean-shaven look, he participated in Finley's mustache promotion. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Of all the A’s, the mustache became the most profitable for Rollie Fingers, who grew his mustache into a handlebar. It became his trademark, brought him endorsements, and made him one of the game’s most recognizable stars.

Ever so wisely, Fingers negotiated Finley’s $300 bonus into his 1973 contract with the A’s. In a comically written press release, Finley discussed his contract negotiations with his ace reliever. “Rollie not only got a substantial increase in salary,” Finley revealed, “but his 1973 contract also includes a year’s supply of the very best mustache wax available. In fact, this is what held up the final signing. I wanted to give Rollie $75 for the mustache wax and he wanted $125 for it.” The two parties compromised at $100. Only in Finley’s Oakland.

As a team, the ’72 A’s turned out to be far more than a group of facial grooming trendsetters and hippie lookalikes. They went on to win 93 games and capture the American League West before ousting the Detroit Tigers in the Championship Series and then upsetting the Cincinnati Reds to win the World Series in seven games.

Jackson played his part, hitting 25 home runs while playing both right field and center field. In the fifth and final game of the playoffs against the Tigers, Jackson tore his hamstring, ending his season. But the mustache – that all important piece of facial hair – remained intact. In 1972, it was all about the mustache.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame