- Home

- Our Stories

- Voices of the Game

Voices of the Game

Since the birth of radio, baseball has come alive over the air

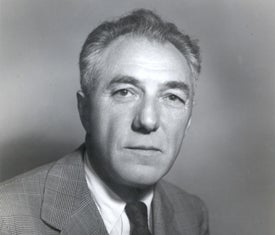

Red Barber was in the mood to give all of us a lesson – a history lesson, that is – on baseball broadcasting.

For someone else, the occasion might have seemed a bit strange. But for Barber, certainly one of the most influential play-by-play announcers in American annals, the time and place of his history lecture seemed perfectly appropriate.

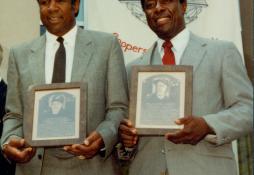

It was Aug. 7, 1978, in Cooperstown, New York. On that day, Barber and Mel Allen, the legendary Yankees voice, became the first two recipients of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Ford C. Frick Award, the highest honor a baseball announcer can receive. Red began his acceptance speech by thanking his presenter, Ralph Kiner. In his famous southern drawl, he recognized his family and gave a nod to Mel Allen, who had spoken moments before. Barber then recalled his surprise and joy upon receiving the “good-news-phone-call” from the Hall of Fame's then-president, Ed Stack.

Then Barber recognized the inductee of that day, Larry MacPhail, for whom he had worked in both Cincinnati and Brooklyn. (MacPhail's induction was posthumous, having passed away in 1975). Among baseball executives, the innovative MacPhail was a leading proponent of both radio and television broadcasting in the early days. He also introduced night games and airplane travel to the big leagues. MacPhail's son, Lee, a longtime baseball front office executive who also served as president of the American League, was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1998. Another son, Bill MacPhail, was president of both CBS Sports and CNN Sports. Larry's grandson is Andy MacPhail, formerly the Baltimore Orioles’ president of baseball operations, and a former general manager of both the Twins and the Cubs. Larry MacPhail was absolutely a key figure in the development of Barber as one of the most prominent baseball voices in the middle of the 20th century.

Back to Red's Cooperstown speech. After a couple of MacPhail anecdotes, suddenly there was a change of gears, as Red delivered his message on some of the history of baseball on the radio:

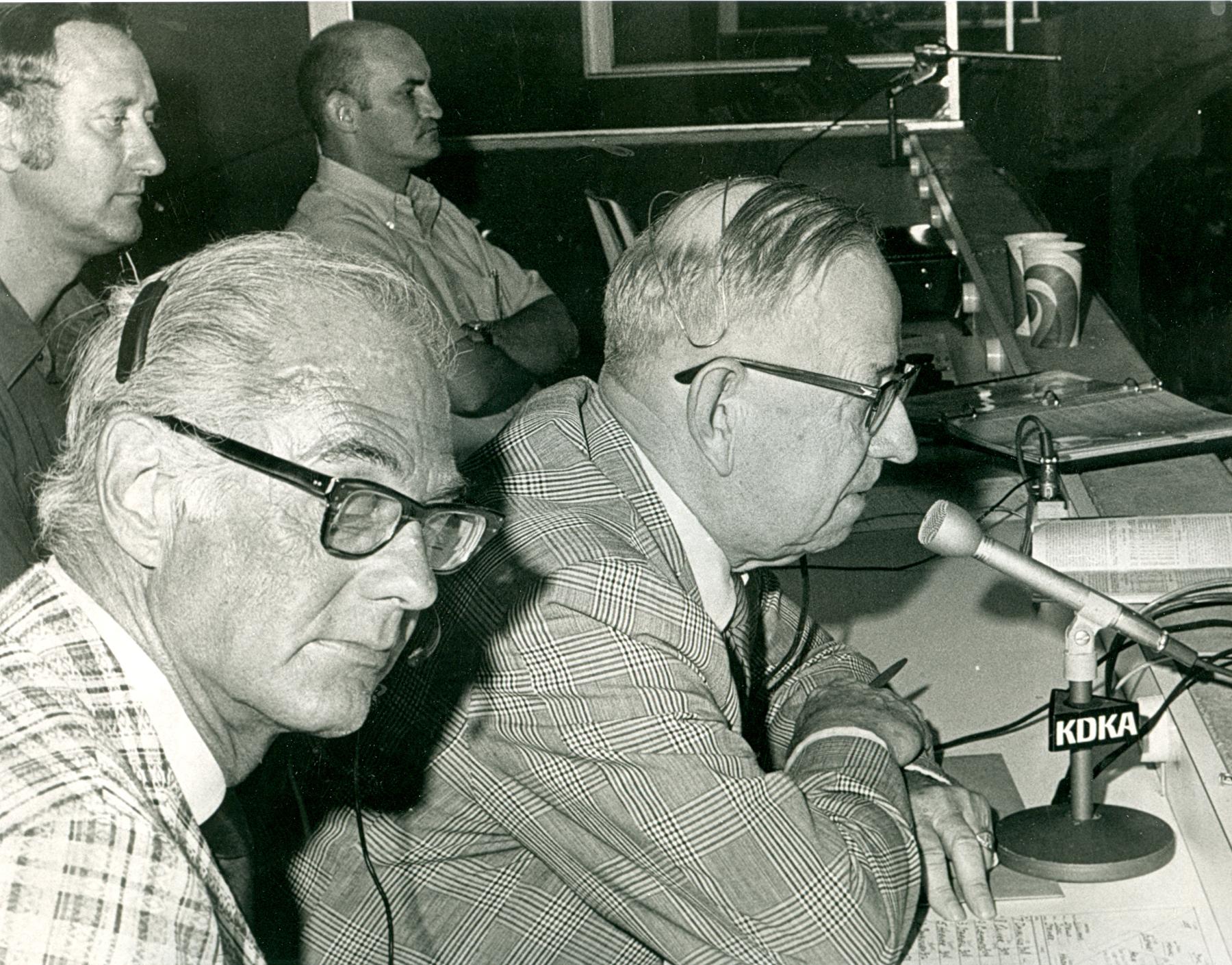

“Now let me go over something very quickly...the first baseball game that was ever broadcast was on the 5th of August, 1921 on KDKA in Pittsburgh, and it was done by Harold Arlin, who was a foreman for Westinghouse.”

Arlin was just 25 years old when he became the first man ever to broadcast a Major League Baseball game. He used a converted telephone as a microphone, as he called the action from a box seat at ground level at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. For the record, the Pirates beat the Philadelphia Phillies that day, 8-5.

Let’s think about Harold Arlin and that first broadcast. Was he nervous? How much preparation did he do? How detailed was his description of the game, if at all? How often did he give the score? Did he even consider things like personality, humor, or style? Probably not. Was he self-conscious? After all, he was announcing from a box seat, and there must have been some fans just a few feet away, listening to him and staring at him in amazement.

What did the first home run call sound like? Or the first bases-clearing double? How did he feel about it afterward?

No recording exists of that broadcast, and Arlin may not have even identified himself on the air. Stations preferred their announcers to be anonymous voices in those days in the fear that the on-air talent would become too popular and harder to control. But Harold Arlin was a pioneer. While his first attempt was probably a bit awkward, it did begin radio’s marriage to baseball, a match made in heaven that continues to thrive to this very day.

“The first World Series that was broadcast was 1921 and the voice was by Tommy Cowan. But he was in a studio with a telephone at his ear, standing at a microphone. A newspaperman at the ballpark (the Polo Grounds) spoke in the phone and told him what was happening in the ballpark, and as best as Tommy could do, he tried to report it over the air. It was so successful, there was no World Series broadcast the next year.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Tommy Cowan was heard on WJZ Radio in Newark, N.J., on October 5, 1921. The station had officially gone on the air four days earlier and management wanted to make a big splash by being the first station to broadcast a World Series game. The Series competitors were the New York Giants and New York Yankees. For the Yanks, 1921 was their first World Series appearance, and their young outfielder, Babe Ruth, had a pretty good season, hitting .378 with 59 homers and 171 RBIs. The day before his big assignment, Cowan paid a visit to the famous inventor Thomas Edison. He requested to borrow Edison's personal phonograph and records to use for music on the World Series broadcast. The “Wizard of Menlo Park” obliged.

Since Cowan relied on someone at the ballgame to feed him information, he was essentially the first man to “re-create” a baseball broadcast. Re-creations were commonplace until World War II. In St. Louis, for example, Harry Caray and his partner, Gabby Street, didn't travel to road games until 1947. Instead, they stayed home and worked in a studio, receiving bits and pieces of information from a Western Union operator at places like Wrigley Field or Ebbets Field. The announcers had to use their imagination and gift of gab to “re-create” the game to make it enjoyable for listeners.

"But then something dynamic happened. Graham McNamee was assigned to broadcast for NBC in 1923, and there is the greatest voice that radio ever had. And baseball broadcasting was on its way.”

McNamee was the first sportscasting “star.” Blessed with a full rich baritone, he wasn't a baseball expert but had a knack for conveying what he saw in great detail, and with a degree of enthusiasm.

McNamee's rise to the top was astonishingly fast. In May 1923, while passing time during a break from jury duty in New York City, he wandered into the studios of radio station WEAF. Somebody heard him speak and stuck a microphone in front of him. McNamee was hired on the spot. That summer, he was assigned to announce a prize fight. That must have gone very well, because in October 1923, McNamee was dispatched to work the World Series, just five months after breaking into the business. He went on to work 12 World Series.

"The first play- by-play regular season was done in Chicago by Hal Totten. He was indeed a pioneer, and baseball broadcasting really exploded in Chicago.”

In those early days, team owners were skeptical of radio, fearing that fans would stay home and listen rather than pay for a ticket to see the game in person. Cubs owner William Wrigley felt differently, that radio had promotional power and local broadcasts would indeed increase interest and attendance. He was right.

Wrigley charged no rights fees to broadcast Cubs games at Wrigley field. It was basically a play-by-play free-for-all, with no “exclusivity” existing just yet.

After Totten began announcing in 1924, WGN's Quin Ryan soon followed. Then WBBM got into the act, with Pat Flanagan on the call. By the late 1920s, Cubs home games were simultaneously transmitted over five stations.

”In 1932, such was the feared effect of radio that the major league clubs came within one or two votes of banning radio broadcasting completely. The Yankees, Giants and Dodgers signed a legal five-year anti-broadcasting pact from 1934 until 1938. 1938 was MacPhail's first year in Brooklyn and the first thing he said was 'I'm going to broadcast next year.'”

The others followed, and 1939 marked the first season that all 16 major league clubs were on radio. Surprisingly, New York City was the last big league town to feature live daily radio baseball coverage.

It was also the year Larry MacPhail brought 31-year-old Red Barber to Brooklyn to become the very first “Voice of the Dodgers.” The rest is history. The “Ole Redhead” became immensely popular in the Big Apple. In his 15 Brooklyn seasons, the Dodgers won five National League pennants and were competitive nearly every year. Never was there a shortage of stars, as those Dodgers featured players like Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe, Peewee Reese and Roy Campanella.

Red Barber was absolutely a play-by-play pioneer. He was a pioneer in preparing for an event and gathering background information. He tenaciously gave the listening audience a detailed description of exactly what was transpiring in a ballgame, with a meticulous attention to accuracy. His fate also dictated that Red was constantly navigating in uncharted waters. A list of Red Barber “firsts” includes:

• Full-time baseball announcer in New York City;

• To broadcast a major league night game (1935);

• To voice a televised major league ballgame (1939);

• To announce an NFL game on TV (1939);

• To call a coast-to-coast NFL Championship Game (1940).

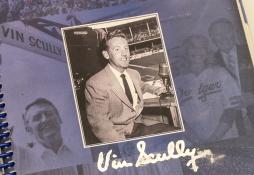

Significantly, Barber was also instrumental in the development of another brilliant redhead, Vin Scully. Beginning with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1950, Scully apprenticed under his watchful eyes and critical ears. The amazing Scully has called Dodgers games in seven decades.

And you know what? You can still hear a piece of Red Barber in every Vin Scully broadcast. The preparation, accuracy, fairness, attention to detail, voice control, and allowing the crowd's roar to take over after a big play. Scully absorbed much of that from Barber. Additionally, since so many current baseball announcers have learned things from Scully, all of America can hear a trace of Red Barber every single baseball day.

Despite the widespread proliferation of televised baseball coverage, the love affair between baseball and radio continues to flourish. Every ballclub has a regional network of 40 to 50 radio stations, or more, and it remains a hot business commodity. Hundreds of millions of dollars exchange hands each year in radio rights fees and sponsorships. TV hasn't vanquished radio yet, and it doesn't look like it'll happen any time soon.

Those of us who make a living as baseball announcers should think about, and appreciate, the trailblazers of our trade. And when an icon like Red Barber wants to deliver a baseball broadcasting history lesson, via a radio recording of his 1978 Hall of Fame acceptance speech, we would all be best advised to pay very close attention.

Pat Hughes is the radio voice of the Chicago Cubs