“We'll never trade you. We think you'll be great, in time. I know it. We’re going to give you all the time you need.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Character and Courage and Cooperstown

Character and Courage and Cooperstown

Today, it is impossible to think of Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Duke Snider as anything but Hall of Famers.

Their bronze plaques shine daily in Cooperstown. Their legend is preserved forever in Terry Cashman’s brilliant ode “Talkin’ Baseball (Willie, Mickey and The Duke).” And their legacy as New York center fielders lives on wherever baseball stories are told.

But like so many other of the game’s iconic stars, success did not come overnight – or without work, struggle and sweat.

The 1950s marked the last decade in which the United States’ most populated area, New York City, had three major league baseball teams and then only until 1958, when the Giants moved to San Francisco and the Brooklyn Dodgers bolted to los Angeles.

The Yankees won the American League pennant every year from 1949-53 and again Several Hall of Famers changed roles on the diamond en route to Cooperstown from 1955-58, while Brooklyn won the National League flag in 1952-53 and again in 1955-56. The Giants won in 1951 and 1954.

But the fans of all three teams won every day because they got to watch three young center fielders, all reaching the majors for the first time by age 20, emerge as Hall of Fame players – albeit after rocky beginnings.

From Oklahoma to New York City

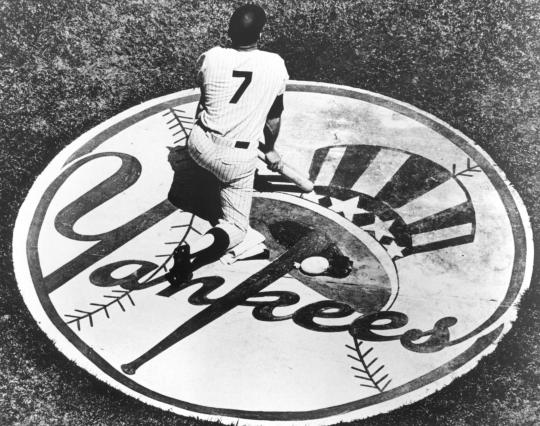

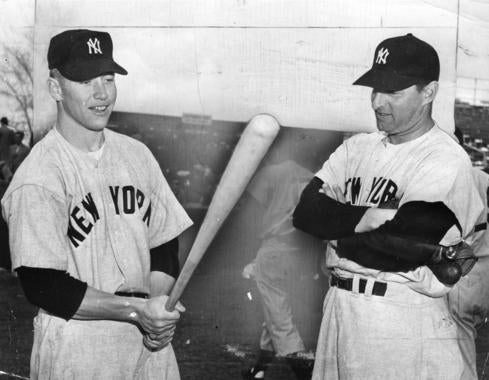

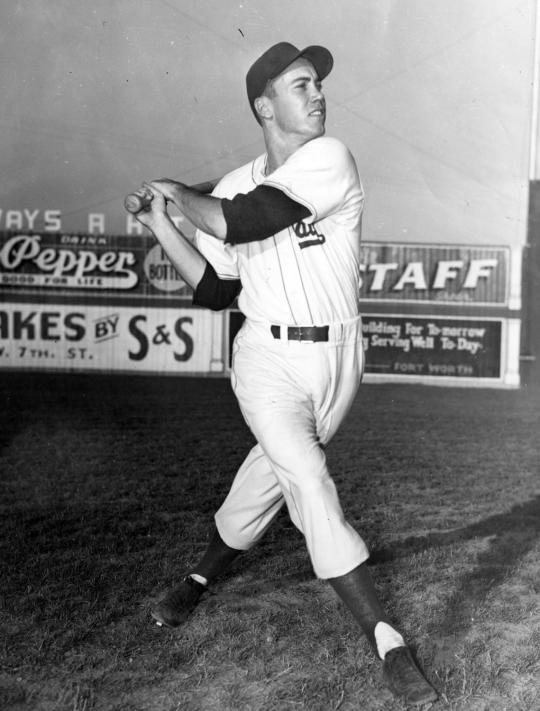

Mickey Mantle made the Yankees’ big league squad in 1951 as a raw, 19-year-old – but a 19-year-old who had batted .400 in spring training, hit nine home runs and made eye-popping catches in the outfield, even though he had been signed as a shortstop.

Manager Casey Stengel had been told the “Commerce Comet,” so named because of his football prowess in his hometown of Commerce, Okla., might not be ready for the majors although no ballplayer before and few since had been so hyped. But Stengel had to like what he saw.

“He should lead the league in everything,” Stengel told reporters. “I got a feeling about that kid.”

By mid-May, Mantle was hitting .300 while batting second and playing right field, next to future Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio.

But DiMaggio did not warm to Mantle. And there was that element of the non-baseball public calling Mantle a draft dodger because he did not pass his Army physical during the Korean War because of the osteomyelitis that would affect Mantle’s left leg and plague his career for its entirety.

Mantle stopped hitting home runs and began striking out much more. He rallied by hitting two home runs on June 19, but Stengel finally benched Mantle – and then the club sent him to Triple-A Kansas City.

“This boy is good,” Stengel said. “Make no mistake about that. His one weakness is he strikes out too often.”

At Kansas City, Mantle started out slowly with three hits in his first 18 at-bats and then got hot. After a three-week trip had ended, he was hitting .345 with six home runs. But he was depressed, fearful that he had blown his opportunity with the Yankees. He was not playing at all well in the field and he was hearing critics of his play and that fact that he wasn't in the Army, where many felt he should be.

His father, "Mutt," the force in his son’s athletic life, drove from Oklahoma to visit his son in Kansas City. And when they were back at the hotel, Mantle told his father he wanted to quit.

“Dad,” Mickey Mantle said. “I can't take it anymore. I want to come home.”

And then, according to Mickey Mantle in later years, his father walked over to the closet and started throwing Mickey’s clothes in a suitcase.

“I thought I raised a man,” Mutt Mantle reportedly said. “I see I raised a coward instead. You can come back to Oklahoma and work in the mines with me.”

Of course, history shows that Mantle stayed. He hit two home runs in his next game and, at one point, knocked in 21 runs in nine games for the KC Blues. Soon he was back in New York, where he would help the Yankees win their third of five straight World Series titles.

“I'm glad, my father knew I was not a failure,” said Mantle, whose dad died the next year.

Mantle went on to hit 536 home runs and some of the longest ever measured.

He became a Hall of Famer after becoming an American folk hero.

‘You’re my center fielder’

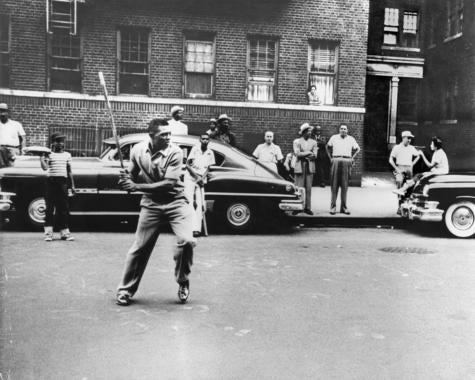

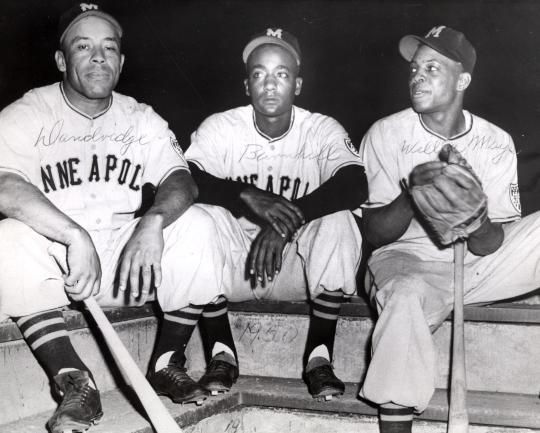

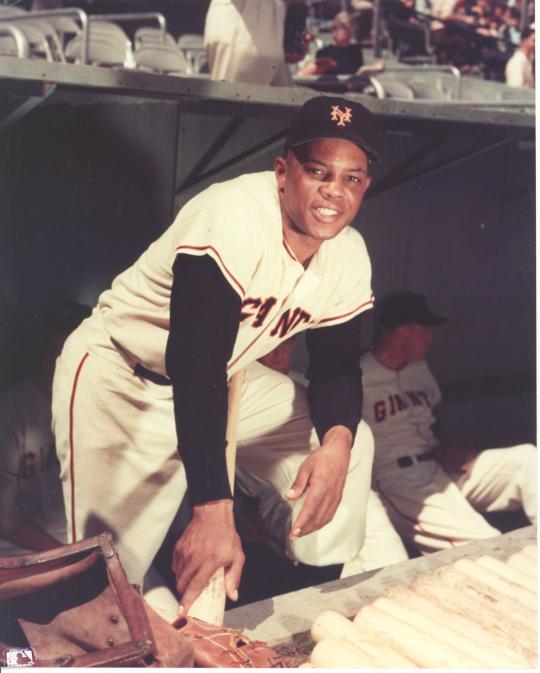

Twenty-year-old Willie Mays, in his second professional season, was enjoying life with the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association in the spring of 1951. After 35 games, the Alabama-born Mays was hitting .477 with 30 runs batted in.

One day in May, he was watching a movie at a theater in Sioux City, Iowa when a message came across the screen, asking him to report to the box office. As Mays later told the story, “I'm saying to myself, ‘Who knows me in Sioux City? This is my first time here.’”

Leo Durocher, the New York Giants manager, knew. On the telephone, Durocher, who would be Mays’ champion in the latter’s early years, told Mays to be on the next plane to New York. Mays recalled Durocher asking him if Mays could hit .250. “I said I could walk that,” recalled Mays.

But the fresh-faced Mays really didn't want to go to New York at all – at least not yet.

Mays said” “No, I don't want to come, Leo. I think I'm having a good year, I don’t think I want to come up there.”

Mays’ early fears that he wasn't quite ready were almost realized. The center fielder went hitless in his first three games, covering 12 at-bats, and then hit a home run off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn at the Polo Grounds. Spahn later joked, “I'll never forgive myself. We might have gotten rid of Willie forever if I'd only struck him out.”

Indeed, Mays was beside himself. He would go hitless another three games, making him one for his first 26 in his first seven big-league contests.

At one point, Mays admitted, “Yes, I was crying. I was crying in my locker and (first-base coach) Freddy Fitzsimmons came in and he saw me and he tells Leo, ‘You better go see about your boy. He's in there crying.’”

Mays later said, "So I'm nervous now. (Durocher) is going to send me back very quickly because that’s the way they do it in the majors. If you don’t hit, you're gone.

“Leo came out and said to me, "You’re my center fielder. Don't worry about anything else. Just go on home and relax.’”

Mays was living on 155th street in Harlem.

“All the people I lived with were from Birmingham,” Mays said. “I knew all the people. I used to come home at night and see a lot of people out there watching. I’m saying, ‘Why are all these people out there?’ They didn't tell me till a year later, that these people were waiting for me to come home.

“They had to make sure I was in bed by nine o'clock every night, and I didn't realize that this was happening.''

Under his friends’ watchful eyes and with Durocher's patience, Mays went on to hit .274 with 20 homers in just 121 games for the Giants in that Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff season and was named National League Rookie of the Year.

He would go into the service for most of the next two seasons, but he would never see Minneapolis again after he exited the Army. In his first season back, Mays, the league batting champion and Most Valuable Player, helped led the Giants to their last world championship in New York in 1954.

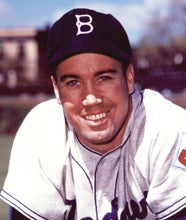

Becoming the Duke of Flatbush

The third member of the fabled trio of New York center fielders in the 1950s was Edwin “Duke” (so named by his father) Snider. The Duke also did not start fast after being brought up by the Brooklyn Dodgers at age 20 in 1947.

Snider hit only .241 with no homers in 83 at-bats that year. He started the next season in Brooklyn but was sent to Montreal, where he hit .327. After being recalled by the Dodgers, Snider would finish with a .244 average and five homers in about one-third of a season.

But in 1949, Snider began the road to Cooperstown by hitting .292 with 23 homers and 92 runs batted in as he helped spark the Dodgers to the National League pennant.

In 1948, Durocher (soon to be out as Dodgers manager), optioned Duke to Montreal in May – but with the promise that he'd be the first player recalled when help was needed. The need came in June.

But Durocher brought up Marv Rackley from Montreal and George Shuba from Mobile.

At the time, Snider said nothing. But when Durocher approached him in Syracuse at an All-Star Game, Snider turned his back. “I don't know you,” Snider related that he said. “I don't know anybody who lies to me.”

After that disappointing season, Snider accepted a job on a sewage project in his California hometown. “I don't know what they (the Dodgers) want from me,” he told some of his friends, “But whatever it is, I haven’t got it.”

Ultimately, Snider conquered himself – his fears and misgivings – and then National League pitching. But there was one more hurdle he had to overcome.

When the Dodgers were caught by and then beaten in a playoff by the Giants in 1951 for the National League title, Snider, whose average had dropped from .321 to .277 that year, was blamed in many circles.

Snider later said, “Looking back now, I guess the worst time of all was late in 1951. I went to (Dodgers owner) Walter O'Malley and told him I couldn't take the pressure. I told him I'd just as soon be traded. I told him I figured I could do the Dodgers no good.”

According to Snider, O'Malley said, “We'll never trade you. We think you'll be great, in time. I know it. We’re going to give you all the time you need.”

Snider turned the corner at that point and in 1980, Snider became the third of the great center-field trifecta to be inducted in the Hall of Fame, following Mantle (1974) and Mays (1979).

But their journey to Cooperstown would have never happened without the character of their convictions – and the courage to press on.

Rick Hummel won the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for meritorious contributions to baseball writing in 2006