He has more bulldog in him than I thought. Bob is just about the hardest worker in camp. I like the kid a lot."

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Baseball cards don’t always show ballplayers at their best. The history of the hobby is rife with such examples.

Some action cards show players awkwardly trying to check their swing, like Bill Melton’s 1972 Topps “In Action” card. Others show players popping up; an example can be found on Harmon Killebrew’s 1972 Topps “In Action” card. In one of the more striking cards of this kind, Dick Green’s 1973 Topps card shows him booting a ball for a clear error, which is somewhat ironic given just how surehanded the second baseman was for the Oakland and Kansas City Athletics.

Then there are the posed photographs. In 1966, Topps issued a card for Clay Carroll, in which he is sweating profusely and has his hair coiffed in such a manner to make him look almost birdlike. (The card also makes him look like a young Jack Nicholson, but that’s another story.) That same year, Claude Raymond posed for his Topps card with…uh…let’s just say his uniform pants weren’t fully fastened. And then, for those who failed to take notice in 1966, Raymond did it again on his 1967 Topps card!

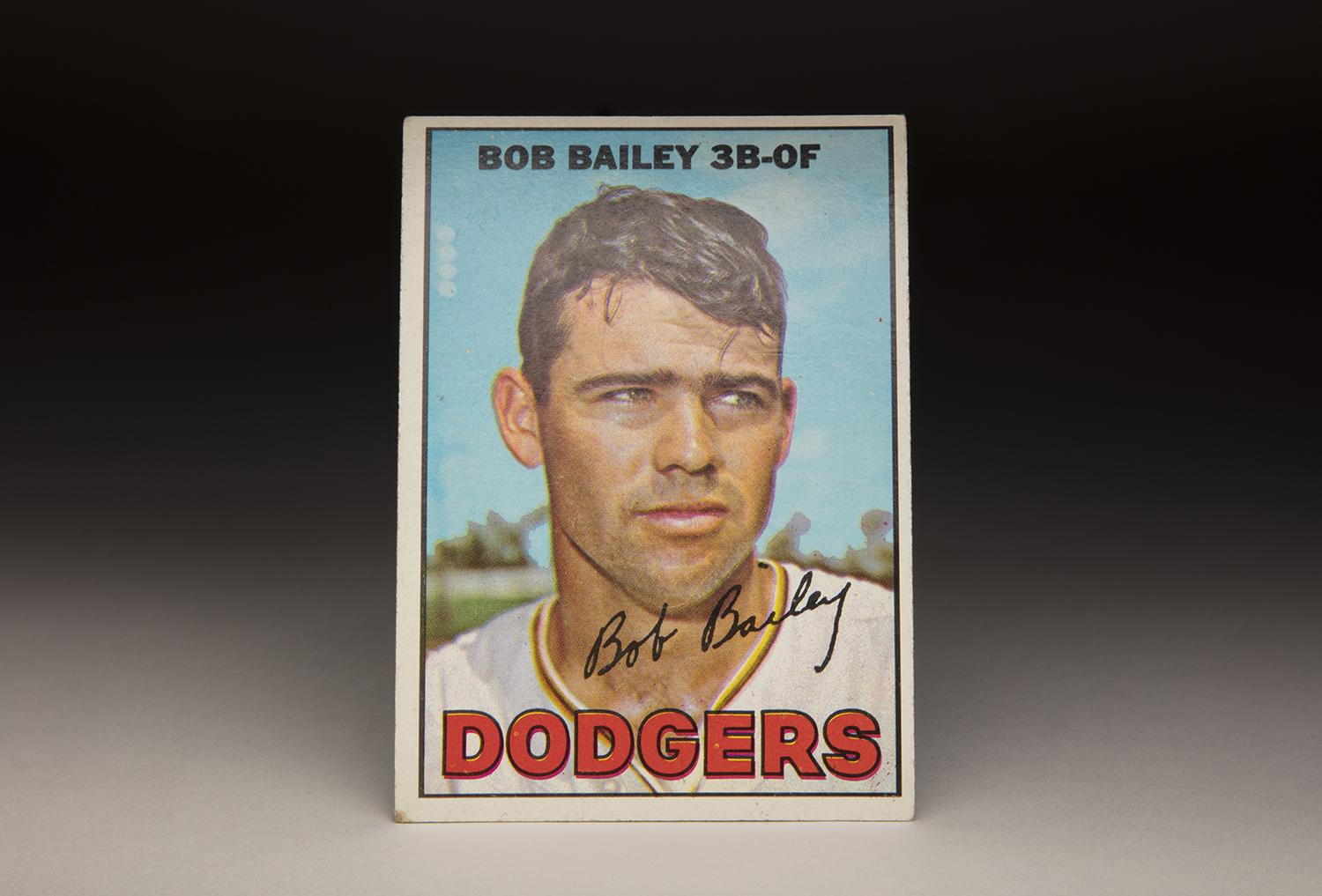

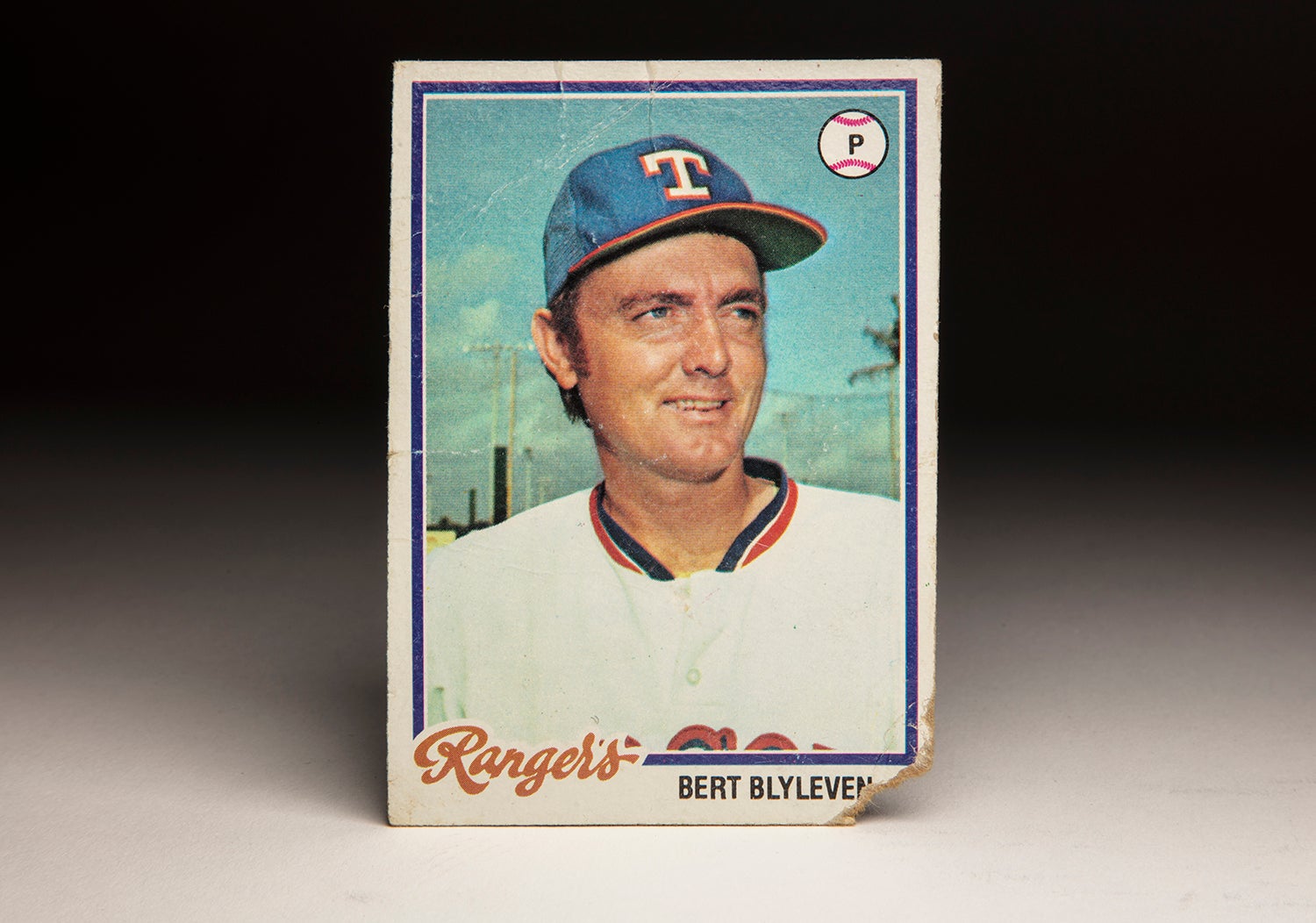

Bob Bailey’s 1967 Topps card is not quite so funny, but it does show him in somewhat of an unkempt moment. His hair is out of place and matted down over part of his forehead, almost certainly because he has just removed his cap. (Unfortunately, the photographer for Topps didn’t give Bailey a comb, or a mirror.) Bailey also appears to be sporting a five o’ clock shadow, a problem for some players who could grow facial hair like a Chia Pet sprouts plants. Tim McCarver has often talked about his own difficulties with shaving, complaining that he had a five o’clock shadow that was practically “ingrown.”

Bailey’s facial expression seems to embody a sense that he is not exactly prepared for the Spring Training visit from the folks at Topps. As he peers to the left, he might be thinking, “Do we have to take this picture right now? Could you give me a moment to tidy up?”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

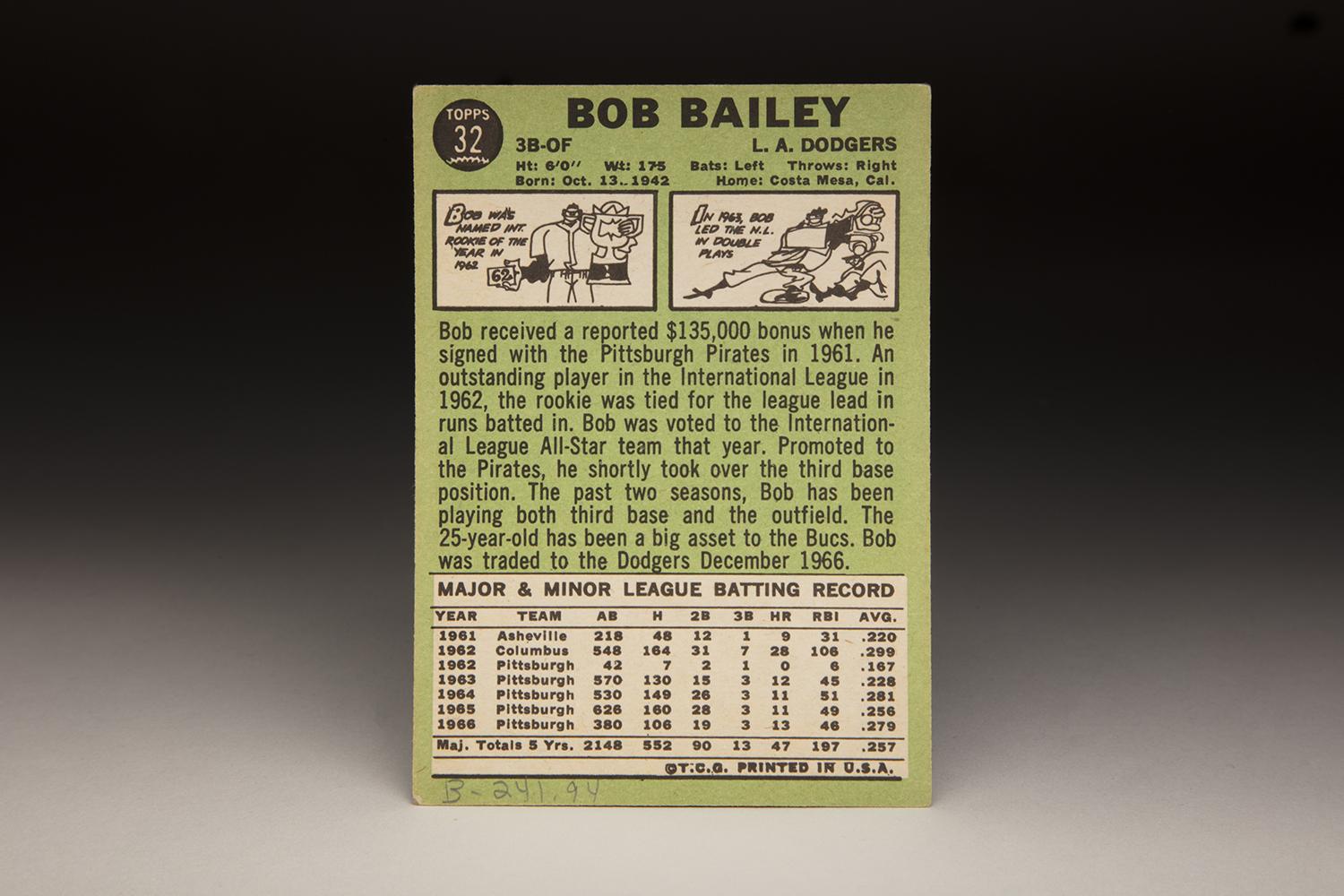

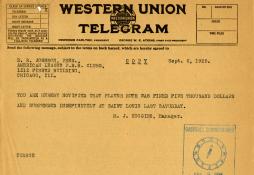

Clearly, this is not Bailey at his Sunday best. Yet, at one time, he was considered the best amateur player in the country, a player who became the subject of an intense bidding war. A high school shortstop of extraordinary talent, Bailey received huge offers in June of 1961 from several teams, including his hometown Los Angeles Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals, his favorite team. Ultimately, Bailey chose the Pittsburgh Pirates, who gave him a bonus of $175,000, a record number for the time. Bailey could have gotten even more. In choosing the Pirates, he turned down money from the expansion Houston Colt .45s, who had offered him a bonus of roughly $200,000.

Still only 18 years old and fresh out of high school, Bailey reported to the Class A Sally League to play for the Pirates’ affiliate at Asheville. The Pirates used him at shortstop, his amateur position, but he made 27 errors in 71 games. Extrapolated over a full major league season, that would have come close to 60 errors.

Bailey fared a little bit better on offense, where his combination of power, speed, and patience showed potential for growth. But his batting average of .220 indicated the problems he had with making hard contact, and sometimes contact at all.

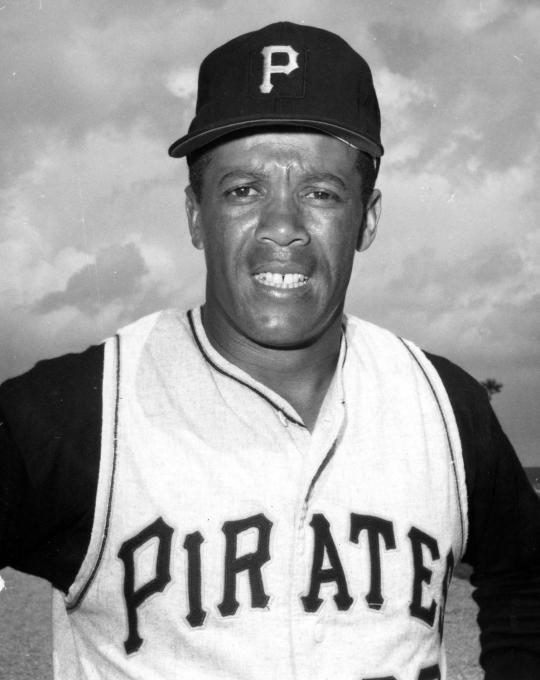

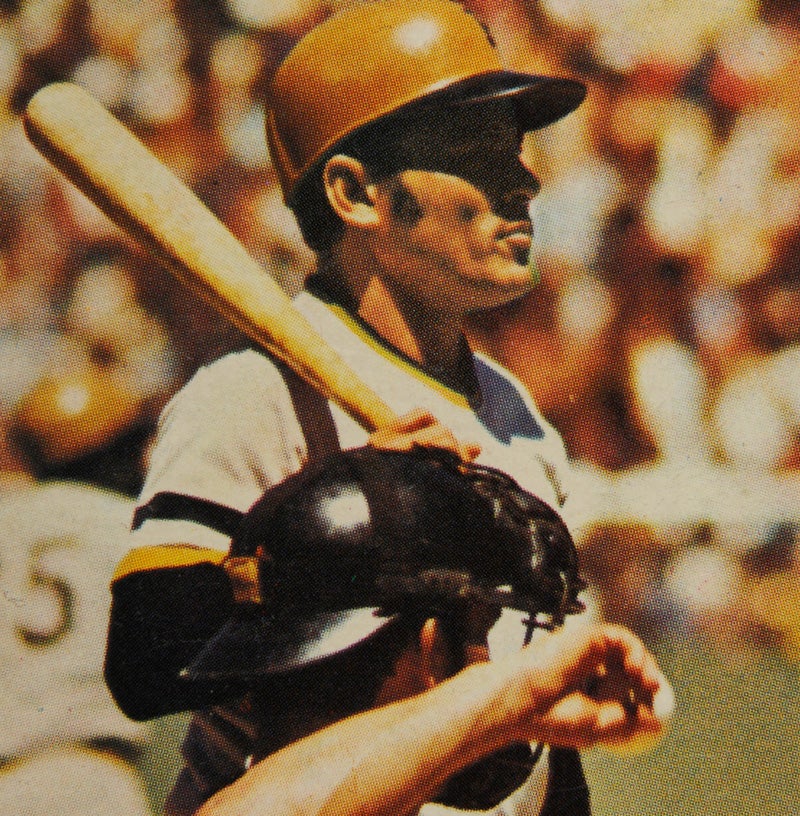

Bob Bailey was once considered the best amateur player in the country, and was the subject of a bidding war featuring several teams in June of 1961. His 1967 Topps card shows him in his first year with the Los Angeles Dodgers, after he was traded by the Pittsburgh Pirates for Maury Wills. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Given his problems as a rookie in pro ball, Bailey should have remained at Class A ball for at least another season, but the Pirates felt they needed to justify his contract and bonus. In 1962, the Pirates promoted him all the way to Triple-A Columbus, their affiliate in the International League. Some scouts felt the move was a mistake, but Bailey soon proved those talent evaluators wrong. Looking comfortable against Triple-A pitching, Bailey batted .299, walked nearly 100 times, and belted 28 home runs. Even at 19 years old, Bailey showed himself to be a quick study – and earned Minor League Player of the Year honors from Sporting News.

The Pirates also made a wise move that summer by moving Bailey off of shortstop and making him a third baseman. Bailey still made more than his share of errors, but his lack of athleticism became less of a problem at the hot corner. Bailey’s footwork and range proved better suited to playing third base, where he didn’t need to cover as much ground.

Bailey’s season-long performance for Columbus earned him a late-season promotion to the Pirates, allowing him to make his major league debut before his 20th birthday. By this time, Bailey had become known as “Beetle,” a reference to the popular “Beetle Bailey” that gained popularity in the 1960s. Appearing in 14 games in September, Bailey struggled at the plate, but not so much that the Pirates changed their mind about his immediate future. The Pirates believed that Bailey would succeed veteran Don Hoak at third base – and soon.

That winter, the Pirates traded Hoak to the Philadelphia Phillies, clearing the way for Bailey to win the third base job in the spring of ’63. Bailey played almost every day, appearing in 154 games, but that was about the extent of the good news. Bailey hit only 12 home runs, batted .228, and struck out nearly 100 times (an unacceptable number for the era). His fielding turned out even worse. Bailey committed a total of 32 errors; he looked clumsy and uncomfortable at the position throughout the year. For a heralded rookie, one whom some anticipated would become an All-Star overnight, it was a rookie season of immense disappointment.

Realizing that they had rushed Bailey into a fulltime role, the Pirates scaled his responsibilities back in 1964. They split his playing time at third base with veteran Gene Freese, while also using the second-year player as an outfielder and shortstop. Bailey took to the new role. He hit better, raising his batting average into the .270 range and lifting his OPS by nearly 50 points. Yet, Bailey remained enigmatic. He did not become one of the team’s vital power hitters, like Roberto Clemente or Donn Clendenon. The Pirates, who once thought they had a future superstar, were beginning to worry that Bailey would be no more than a role player.

The start of the 1965 season seemed to indicate a change in fortune. On Opening Day, Bailey hit a game-ending home run against Hall of Famer Juan Marichal. Rather than ignite a breakout, it simply led to another year of disappointment. Other than drawing more walks, Bailey’s hitting regressed in almost every way. On defense, Bailey played more regularly at third base, but his fielding prowess remained spotty and erratic.

Bailey would play better in 1966, but the season hardly represented a complete breakthrough. With a .279 batting average and 13 home runs (a career high), Bailey showed some progress. The Pirates also might have reminded themselves that he was still only 23 years old. There was still time for Bailey to step up and become the star that the scouts had once envisioned.

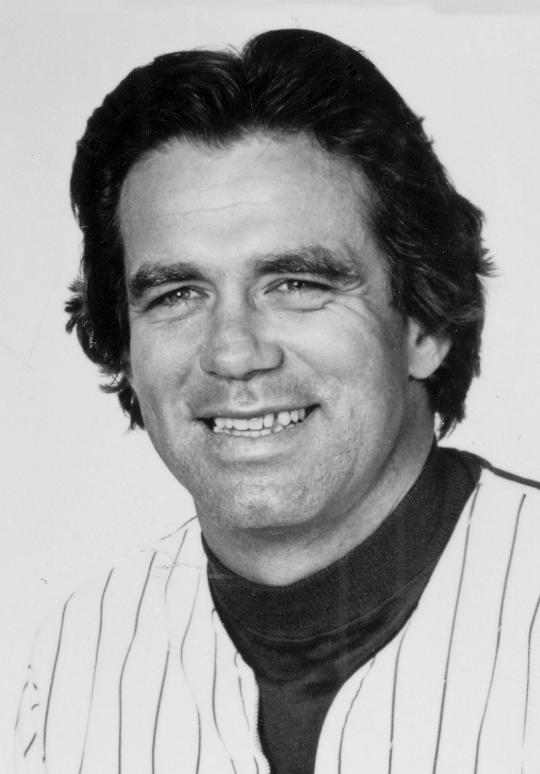

Rather than continue a patient approach, the Pirates decided to move on. Concerned that Bailey would never live up to the bonus he had once received, the Pirates made a trade that winter, sending Bailey and an unproven Gene Michael to the Dodgers for veteran speedster Maury Wills. Based solely on name recognition, the Pirates won the deal; Wills had garnered the National League MVP Award only four years earlier. In reality, the trade was short-sighted. Wills was 34 and no longer the game-changing speedster or everyday shortstop that he had been during his Dodgers prime.

The trade further explains Bailey’s Topps card. Seen without a cap, Bailey is actually wearing a Pirates jersey (notice the gold trim around the color), even though Topps has designated him a member of the Dodgers. A native of Long Beach, Bailey was thrilled with the trade that sent him home to Southern California. Upon reporting to the Dodgers’ camp in Vero Beach, he immediately impressed everyone with his attitude and work ethic. “He has more bulldog in him than I thought,” manager Walter Alston told Bob Hunter of Sporting News. “Bob is just about the hardest worker in camp. I like the kid a lot.”

For the Dodgers, Bailey played a new position, opening up the 1966 season in left field before settling into a role as a utility man. Bailey played the outfield, third base, shortstop, and first base, but hit poorly. By season’s end, he had compiled a .227 batting average with only four home runs, the worst numbers of his career. Playing at Dodger Stadium didn’t help a power hitter like Bailey. If he thought that Forbes Field posed a difficult hitting environment, he came to realize that Dodger Stadium ranked as even tougher. Regarded as arguably the toughest ballpark for hitters in the major leagues, Dodger Stadium plagued batters with its long dimensions, high mound and difficult sight lines.

In 1968, Bailey fared no better, his situation exacerbated by the Year of the Pitcher. With his stock at an all-time low, the Dodgers left him unprotected in the expansion draft. To the shock of many, none of the four expansion clubs selected Bailey. Not really wanting Bailey anymore, the Dodgers sold his contract to the expansion Montreal Expos, accepting only cash in return.

On the surface, Bailey’s career seemed in jeopardy. If he failed to make an impact for an expansion club, he could soon be looking at baseball’s unemployment line. Thankfully, Bailey received the break that he needed in playing for a new manager, Gene Mauch, formerly the manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. Mauch wisely switched Bailey to first base, a position that lessened his fielding demands and allowed him to concentrate more on his hitting. Bailey showed improvement, lifting his OPS to .756 and his home run total to nine. Those numbers didn’t represent a career year, but they did indicate a bounceback.

One of the game’s best teachers and a master of fundamentals, Mauch worked with Bailey to resurrect his career. Mauch so believed in Bailey that he made him the starter at first base, while benching Donn Clendenon, Bailey’s former teammate in Pittsburgh. When Clendenon left town in a trade, he fired a parting shot at Mauch, and didn’t spare Bailey. “If Mauch can make a hitter out of Bailey,” Clendenon told a Montreal writer, “I’ll kiss him at home plate on Bat Day.”

Bailey deflected Clendenon’s remarks with grace, refusing to retaliate publicly. “When I first heard it, I was surprised because you don’t expect that kind of thing from a ballplayer about another ballplayer,” Bailey told sportswriter Bill Christine, “but you know, at the time he made that remark, the way I was swinging the bat, he wasn’t too far wrong.”

Supported by Mauch, the classy Bailey busted out for the Expos in 1970. Though he split his time between third base, first base, and left field, he found a stable role in the middle of Mauch’s lineup. In an August game against Houston, Bailey displayed the kind of raw power the Pirates had once envisioned. Playing at the Astrodome, Bailey belted a long home run to left field, planting the ball in the fourth deck of the cavernous indoor stadium. “That’s the biggest home run I’ve ever seen,” Mauch told the Montreal Gazette. When a reporter asked Mauch about the length of Richie Allen’s home runs in Philadelphia, Mauch weighed in. “Oh yeah, bigger than anything Richie Allen ever hit.” Given the talents of Allen, that amounted to high praise for Bailey.

That home run epitomized the breakout season of Bailey’s career. He blasted 28 home runs (15 more than his previous best), slugged .597, and put up an OPS of slightly better than 1.000. At the age of 27, Bob Bailey had suddenly become one of the National League’s most feared hitters.

Although Bailey would never achieve such numbers again, he remained a dangerous hitter while also making the transition back to third base, where he succeeded the wonderfully named Coco Laboy. In 1973, he hit 26 home runs. The following summer, he drew 100 walks.

It was not until 1975 that Bailey began to show signs of slippage and had to accept a role as a part-time left fielder and backup third baseman. With his waistline expanding and his bat speed slowing, the 32-year-old slugger became susceptible to hard fastballs, especially up in the strike zone. Injuries also played a part, as he suffered a broken bone in his hand that forced him to miss a significant stretch of the season.

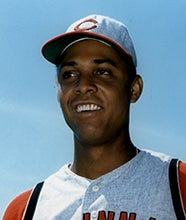

Bob Bailey began his professional baseball career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, and would play there for five seasons. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

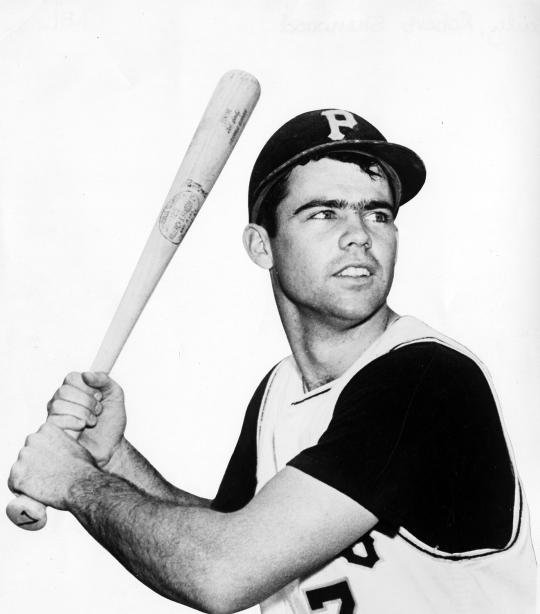

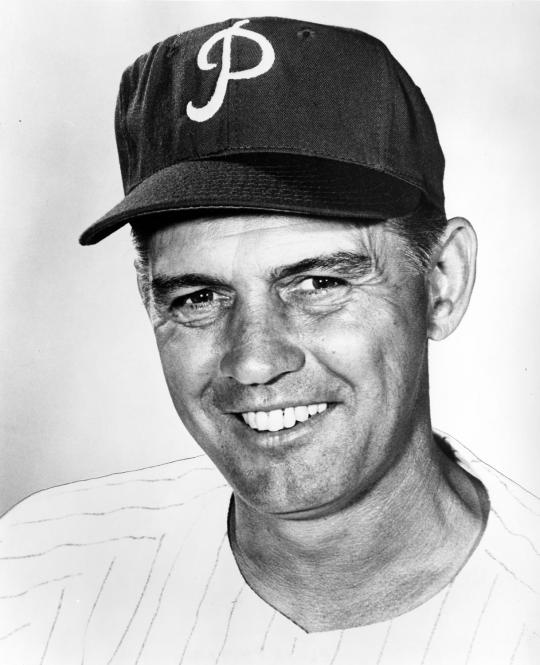

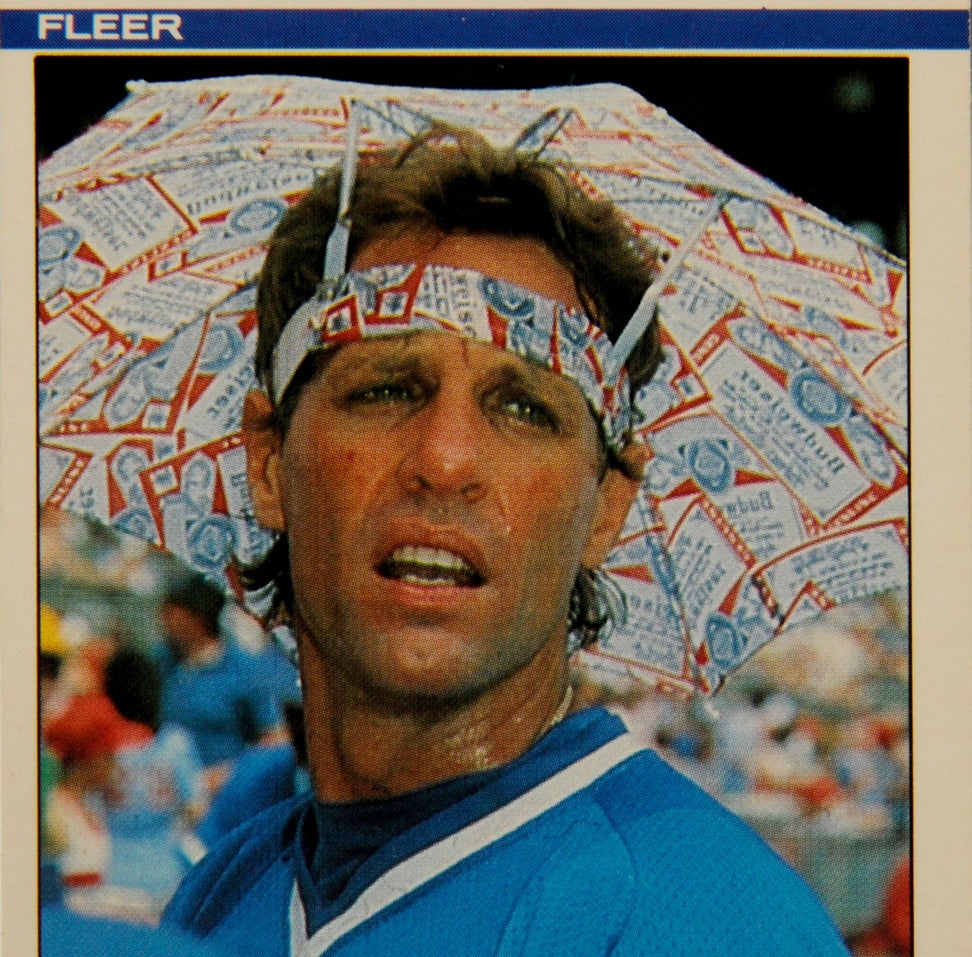

Like Bob Bailey, Tim McCarver (pictured above) also complained of his facial hair growing too quickly. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

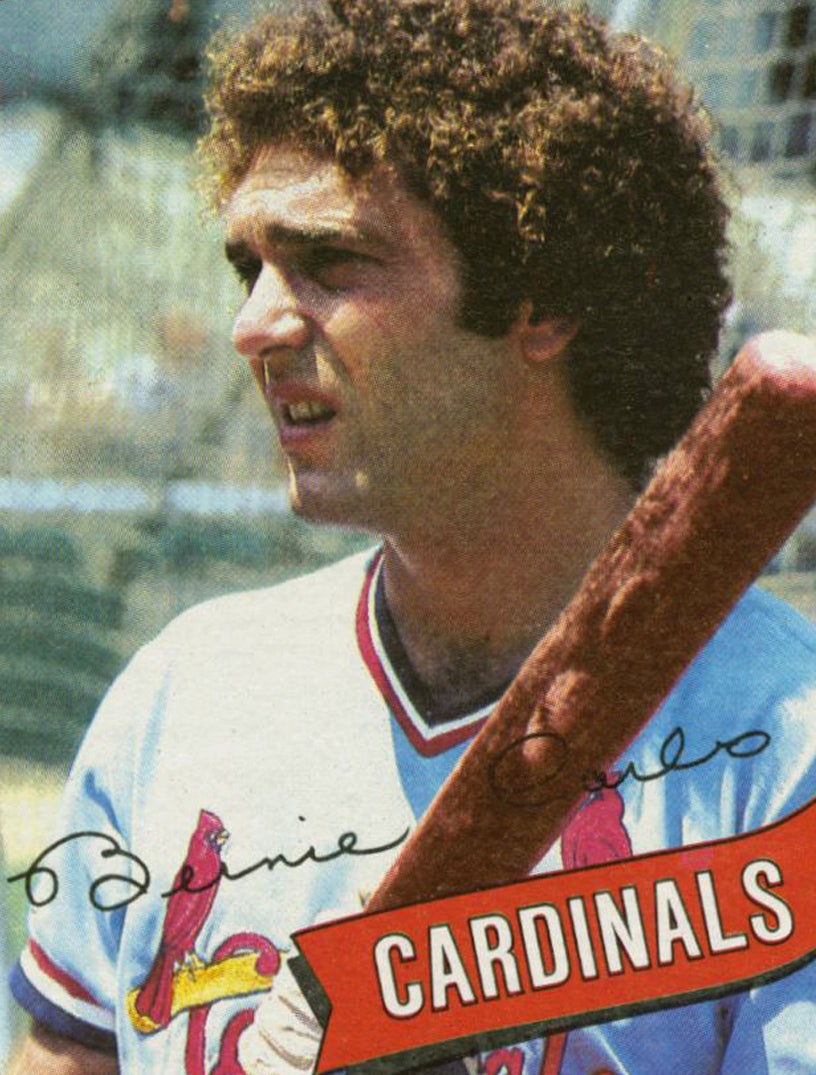

Maury Wills was traded by the Los Angeles Dodgers for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael of the Pittsburgh Pirates on December 1, 1966. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Concerned that Bailey was nearing the end of his career, the Expos felt it best to trade him at the 1975 Winter Meetings. Pulling off a deal with the world champion Cincinnati Reds, the Expos acquired veteran right-hander Clay Kirby for Bailey.

With the Reds loaded with high-end talent at first base (Tony Perez) and third base (Pete Rose), Bailey settled into a bench role for the “Big Red Machine.” Bailey adjusted well, hitting .298 with a .508 slugging percentage in just under 150 plate appearances. Those numbers supported an argument for Bailey as one of the best bench players in the National League.

For the first time in his career, Bailey headed to the postseason. He never did appear in a playoff or World Series game that fall (as Sparky Anderson stayed with his starting players almost exclusively), but still picked up his first world championship ring when the Reds swept the New York Yankees in a four-game Series rout.

Bailey returned to the Reds in 1977, but the team eventually fell out of contention. In September, the Reds made a waiver deal with the Boston Red Sox, sending Bailey to Beantown for minor league lefty Frank Newcomer. Engaged in an epic struggle with the Yankees for the American League East title, the Red Sox used Bailey as a pinch-hitter in two late season games. The Red Sox fell short of the Yankees by two games, denying Bailey his second consecutive postseason appearance.

The Red Sox brought Bailey back for the 1978 season, hopeful that he could fill a role as a part-time DH and backup third baseman and outfielder. By now, Bailey’s hitting skills and his physical conditioning had eroded. With his bat speed slowed, Bailey struggled in 94 at-bats. On Oct. 2, the day the Red Sox played the Yankees in a historic tiebreaking game, Bailey made his final major league appearance. Bailey returned to the Red Sox for the 1978 season. Called upon as a pinch-hitter to face Yankees closer Goose Gossage in the bottom of the seventh, Bailey represented the tying run but found himself overmatched against the future Hall of Famer’s fastball. Bailey struck out on three pitches.

When the Yankees finished off the Red Sox that afternoon, Bailey’s season came to an end. So, too, did his career. At the age of 35, Bailey knew that it was time to retire.

Known as a smart level-headed player, Bailey turned to minor league managing and also worked as a minor league hitting instructor for the Expos. By his own admission, he struggled with alcoholism during that time, which he believes prevented him from managing in the major leagues.

Bailey has also admitted to having problems with gambling, before eventually overcoming the habit. Frankly, I didn’t hear much about him until the mid-1990s, when I happened to be watching Yankees Old-Timers Day on television. Wearing the uniform of the Red Sox, Bailey stepped to the plate. I was stunned at his appearance. Bailey had put on a tremendous amount of weight, easily surpassing 300 pounds.

Bailey’s weight made me concerned about his health, but more than 20 years later, he remains with us. Diagnosed with diabetes, he has lost much of that excess weight and has stopped drinking. Known as a humble and deeply religious man who willingly pokes fun at himself for his fielding problems at third base, Bailey nonetheless remains pleased with his legacy.

Bailey might not have appreciated his 1967 Topps card, but he remains grateful for the opportunity to play in the major leagues for nearly two decades. With 189 career home runs and a World Series ring in his possession, Bailey had good reason to be proud.

He passed away on Jan. 9, 2018.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum