- Home

- Our Stories

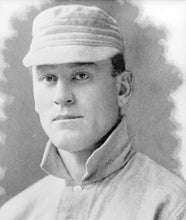

- 19th century star Harry Stovey

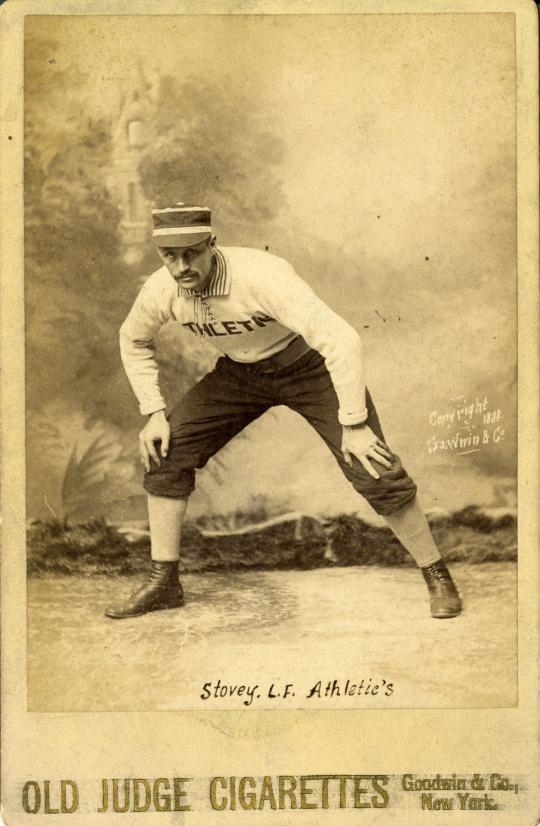

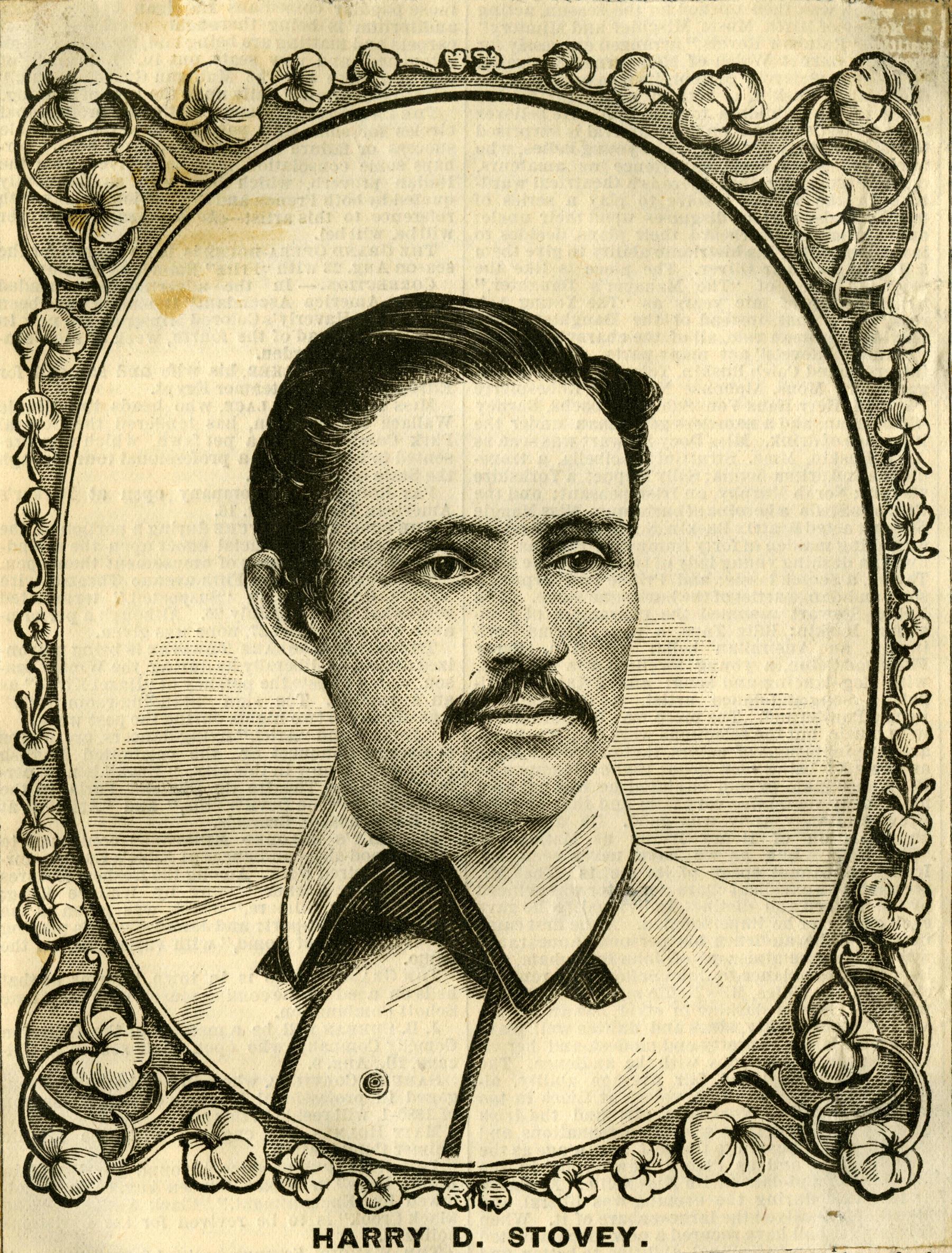

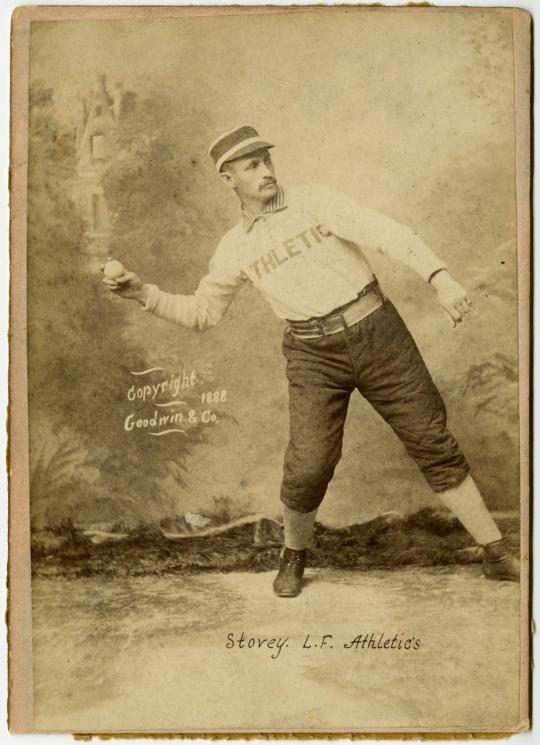

19th century star Harry Stovey

His rare combination of power and speed made him one of baseball’s first dual threats. Now, more than 100 years after his retirement, Harry Stovey stands at the threshold of the Hall of Fame.

Stovey, a champion player in three different leagues during the 19th century, is one of 10 finalists on this year’s Pre-Integration Committee ballot at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The Pre-Integration Committee will vote at baseball’s Winter Meetings in Nashville, Tenn., and the results of the vote will be announced Dec. 7.

The 10 candidates on the Pre-Integration Committee ballot are: Doc Adams, Sam Breadon, Bill Dahlen, Wes Ferrell, August (Garry) Herrmann, Marty Marion, Frank McCormick, Chris von der Ahe, Bucky Walters and Stovey. Any candidate who receives votes on at least 75 percent of all ballots cast will be enshrined in the Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2016.

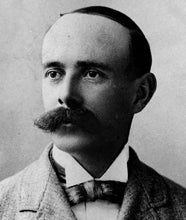

Born Dec. 20, 1856 in Philadelphia, Stovey, originally born as Harry Stowe, adored the game of baseball from an early age. His mother, however, abhorred the sport, and so at the age 20 the young Stow changed his surname to ‘Stovey’ so that she wouldn’t find his name in the newspaper game stories.

The man with a new alias began his baseball career with the League Alliance’s Philadelphia Defiance Club in 1877 before switching over to the crosstown Athletics midway through the year. Two more years with the minor league New Bedford (MA) Clam-Eaters followed before Stovey and manager Frank Bancroft joined on with the nascent Worcester Ruby Legs of the National League for 1880.

While the Ruby Legs struggled, Stovey quickly ascended to main draw status, leading the NL in triples (14), home runs (6) and extra base hits (41), and finishing second in runs (76) and total bases (161) during his rookie season.

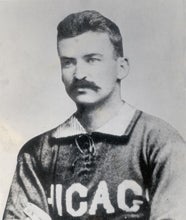

When Worcester disbanded at the end of 1882, Stovey returned to Philadelphia to suit up for a new Athletics club in the upstart American Association. Entering his prime at 26, Stovey’s impact was immediate: He led the AA in runs (110), home runs (14), doubles (31), slugging percentage (.506) and total bases (213). Recaps from the championship game on Sept. 28, 1883 further illustrate Stovey’s dominance, as he singled, stole second, tagged up to third base on an infield fly and scored on a wild pitch to win the title for Philadelphia over Louisville in the 10th inning.

The 1883 triumph was a glimpse of outstanding years to come for Stovey. He led or tied for the league lead in home runs five times (1883-86, 1889), runs four times (1883-85, 1889), hits twice (1883-84), average once (.404 in 1884, though somewhat disputed), RBI once (1889) and stolen bases once (1886). The first baseman and outfielder was also described as a five-tool player who possessed steady hands to go with a rifle arm.

Though he was nicknamed “Gentleman Harry” for his clean play, Stovey’s peers maintained that he was as fierce a competitor as anyone. He was the first to wear sliding pads after developing leg bruises from his reckless runs on the basepaths. He is also widely credited as the first to slide with his spikes in the air.

“He could beat Ty Cobb and Hal Chase,” wrote a sportswriter of Stovey’s drive in 1883. “And when it came to daring, he would take more chances than a sailor at a turkey raffle.”

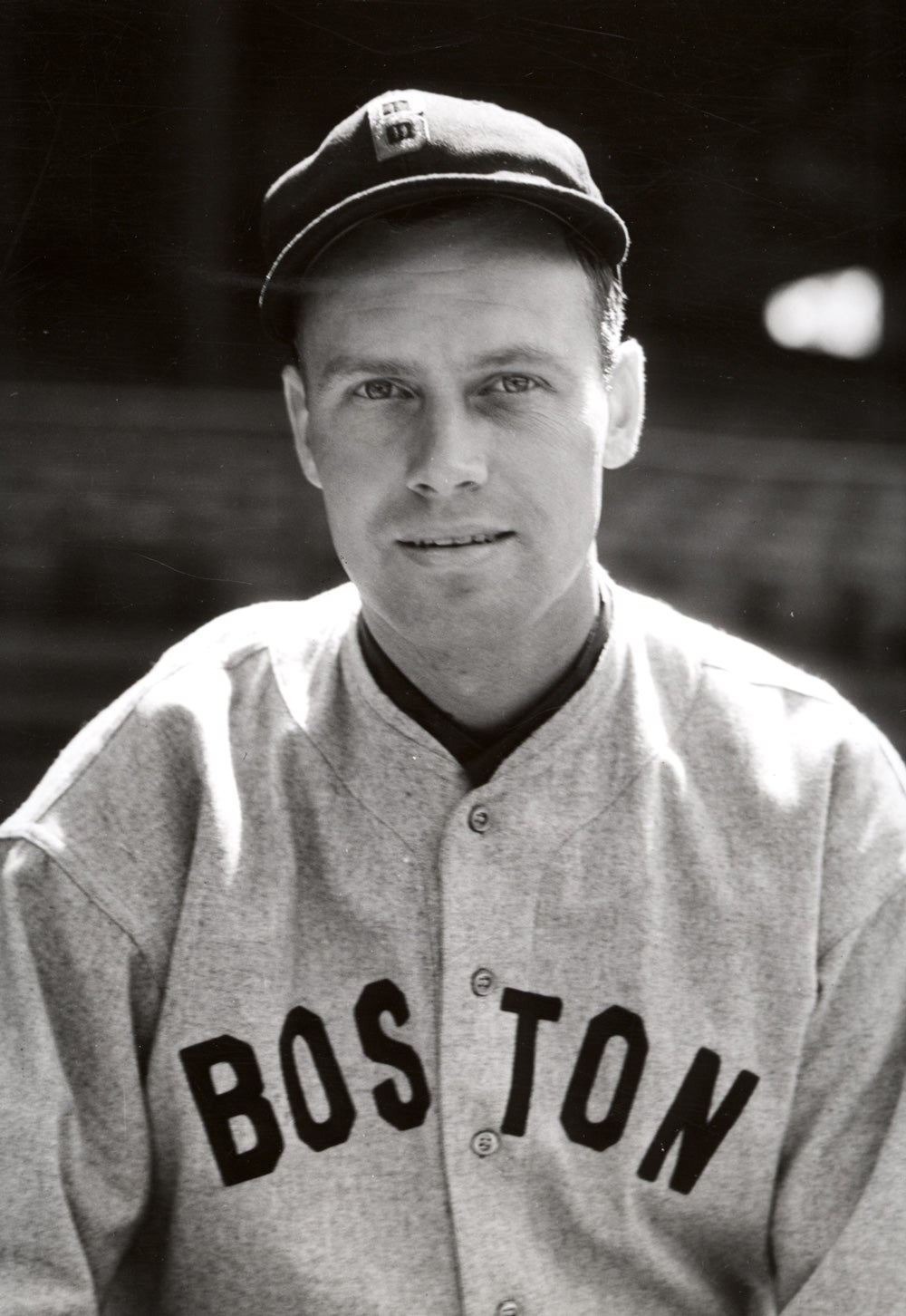

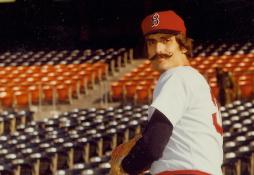

When the AA folded in 1889, Stovey was the league’s career leader with 76 home runs and 883 runs scored. At 33, he jumped to the Player’s League, and led the Boston Reds to the championship with a .299 average and league-leading 97 steals.

The Player’s League was over almost as soon as it began after the 1890 season. After an aggressive pursuit by Pittsburgh, Stovey ultimately remained in The Hub to play with future Hall of Fame manager Frank Selee on the National League Beaneaters. Now 34, he enjoyed his final dominant season as he led the senior circuit with 20 triples, 16 round-trippers, a .498 slugging percentage and 271 total bases – with 57 steals thrown in for good measure. With Stovey and future Hall of Famers John Clarkson, King Kelly and Joe Kelley in tow, the Beaneaters claimed the 1891 NL crown – Stovey’s third title in three different leagues.

In 1892, Stovey finally began showing signs of decline and was released by Boston midseason. He filled out his career with quick stops in Baltimore and Brooklyn before hanging up his famous spikes for good in June 1893. Twenty-seven years later, as Babe Ruth began his famous assault on major league baseball’s record books, Stovey’s name still stood at third all-time with 122 home runs. His stolen base totals vary widely – from over 1,000 to just over 500 – because of old-time rules which awarded steals for going from first base to third on a teammate’s hit. Still, his influence as one of baseball’s first speed demons remains absolute.

Stovey returned to his hometown of New Bedford, where he worked as a policeman. He passed away Sept. 20, 1937 at the age of 80.

Matt Kelly is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum