- Home

- Our Stories

- The Negro National League is Founded

The Negro National League is Founded

African Americans played baseball – and played the game at a very high level – since the game spread across American territories during the Civil War. But many of those talented players would likely not have become the legends they are today without the visibility offered by an organized league in which they could play.

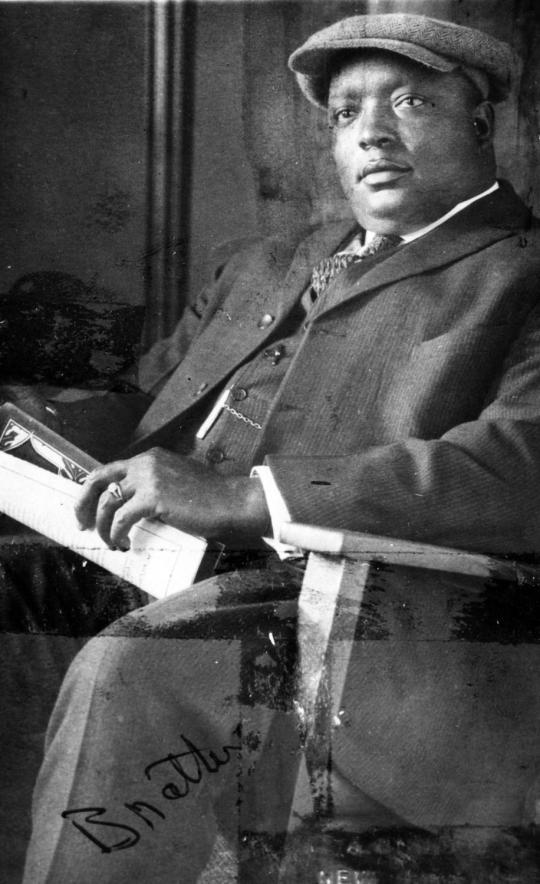

On Feb. 13, 1920, Hall of Famer Andrew “Rube” Foster and his fellow team owners filled that void when they came together to create the Negro National League.

When baseball first became organized in the 1860s, a small handful of Black players took the diamond alongside their white teammates. But with Jim Crow laws and prevalent segregationist sentiment still left over from the Civil War, the careers of talented Black players like Moses Fleetwood Walker, Bud Fowler and Frank Grant were short-lived. By the turn of the 20th century, unwritten rules and “gentleman’s agreements” between owners had effectively shut Black ballplayers out of big league competition.

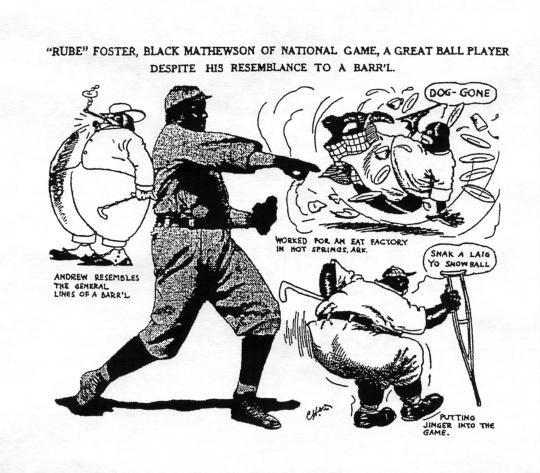

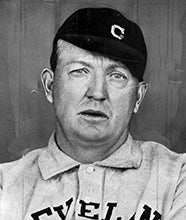

Still craving a means to play, Black players formed their own teams and barnstormed across the country to find competition. It was in this environment that Rube Foster made a name for himself as a player and then a manager. A dominant pitcher, he won 44 games in a row for the Philadelphia Cuban X-Giants in 1902 and began a legendary career that inspired fans to call him the “Black Christy Mathewson.”

“Rube Foster is the pitcher of the Leland Giants, and he has all the speed of a [Amos] Rusie, the tricks of a [Hoss] Radbourne (sic), and the heady coolness and deliberation of a Cy Young,” wrote Frederick North Shorey of the Indianapolis Freeman in 1907. “What does that make of him? Why, the greatest baseball pitcher in the country; that is what the best ball players of white persuasion that have gone up against him say.”

Foster partnered with John Schorling, son-in-law of Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, to form the Chicago American Giants in 1911. He negotiated for the team to play at the White Sox’s old stadium, South Side Park, where he developed one of the finest Black baseball teams in the country. As manager, Foster taught his players the strategies of “inside baseball” that managers like the New York Giants’ John McGraw had successfully employed in the white National League. Aggressive, daring and – most importantly – exciting, the American Giants consistently outdrew both the White Sox and the Cubs and established a style that would later become symbolic of Negro National League play.

While Black baseball players drew crowds during the 1910s, their teams’ gate receipts were tightly controlled by white booking agents. The agents dictated when and where Black teams could play, and they subsequently passed little of the games’ attendance revenues on to team owners. Any team owner who objected to the scheduling practices of the agents ran the risk of losing a venue in which to play.

“The wild, reckless scramble under the guise of baseball is keeping us down,” Foster said, “and we will always be the underdog until we can successfully employ the methods that have brought success to the great powers that be in baseball of the present era: organization.”

While Foster was enjoying considerable financial success with his American Giants, he remained frustrated by how fellow owners and players were being treated by booking agents. In 1919, he began writing a series of columns in the Chicago Defender newspaper in which he advocated the need for a Black professional baseball league that would “create a profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession… keep Colored baseball from the control of whites (and) do something concrete for the loyalty of the Race.”

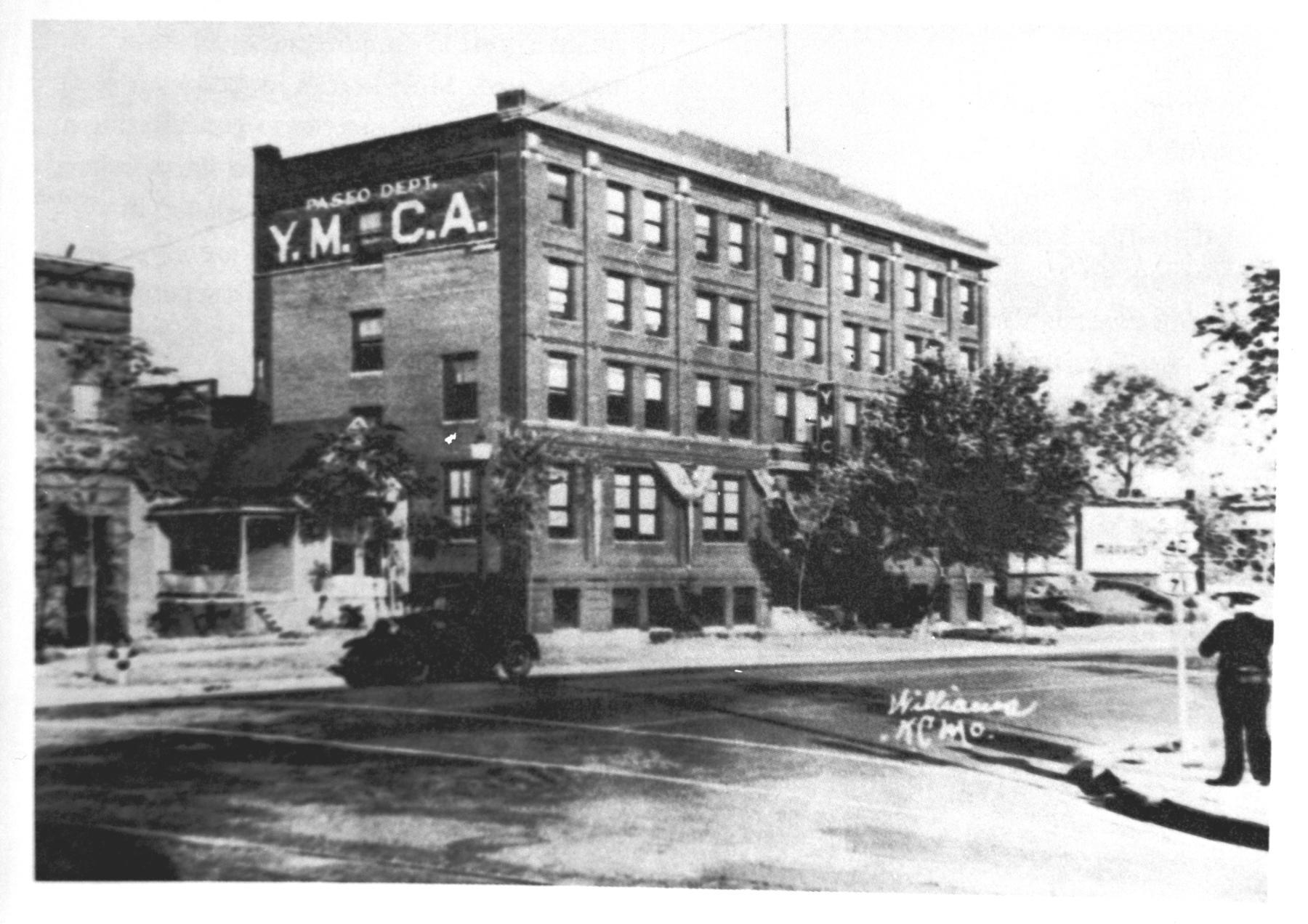

Foster had to work tirelessly to persuade both his fellow owners, who were reluctant to cede their autonomy, and players who feared organization would negatively affect their salaries. In February 1920, Black team owners convened at a YMCA in Kansas City to discuss the prospect of a colored baseball league.

Foster surprised them all when he showed up with an official charter document for the Negro National League already in hand.

“To his undying credit, let it be said that he has made the biggest sacrifice,” said NNL secretary Ira Lewis of Foster. “For be it known that his position in the world of colored baseball was reasonably secure. Mr. Foster could have defied organization for many years. But, happily, he has seen the light – the light of wisdom and the spirit of service to the public.”

Featuring teams in Chicago, Cincinnati, Dayton, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City and St. Louis, the NNL adopted the slogan, “We Are the Ship, All Else the Sea” as a pledge to set its own course. Many teams discovered financial success coming out of the gate; Foster’s American Giants drew nearly 200,000 spectators during the 1921 season.

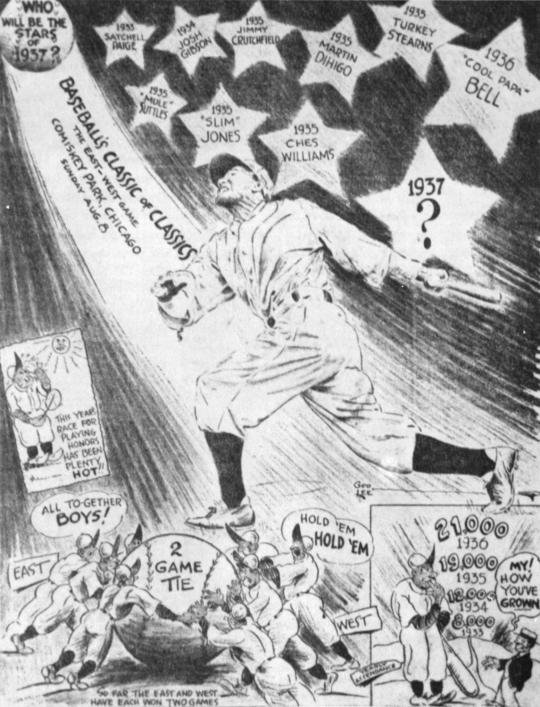

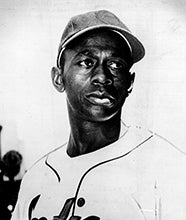

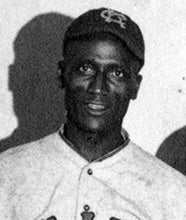

The NNL created a forum where many star players could make a bigger name for themselves – especially to white audiences. Future Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell, Martín Dihigo, Bill Foster, Judy Johnson, Satchel Paige and Turkey Stearnes all flourished in the NNL, along with many others. The league would also inspire rival organizations like the Southern Negro League and the Eastern Colored League, whose teams would square off against NNL squads in the annual Negro League World Series.

Foster continued to manage his Chicago club and serve as NNL president until a nervous breakdown led to his retirement in 1926. He passed away in 1930 – 51 years before his election to the Hall of Fame – and soon the financial hardships of the Great Depression forced nearly every colored baseball league, including the NNL, to shut down.

The league would resurface, however, as the Negro American League in 1937, with many of the same teams from the old Negro National League. The NAL would continue full-time and robust operations until one of its own, the Kansas City Monarchs’ Jackie Robinson, broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947.

Though Robinson’s breakthrough into the major leagues signaled the eventual decline of the Negro Leagues, the organization of colored baseball undoubtedly pushed the game as a whole into unchartered territory. The NNL featured night games far before the big leagues, and introduced its East-West All Star Game during the same year as MLB’s Midsummer Classic in 1933.

Most importantly, the creation of the Negro Leagues proved that Black players could play on even terms with their white counterparts – and draw just as much interest from baseball fans.

“The leagues died having served their purpose,” said baseball writer Steven Goldman, “shining a light on African-American ballplayers at a time when the white majors simply did not want to know.”

Matt Kelly was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum