- Home

- Our Stories

- Just ‘Kidding’: Five Hall of Famers have earned the youngest of nicknames

Just ‘Kidding’: Five Hall of Famers have earned the youngest of nicknames

Back in the 1980s, when HBO was still known as Home Box Office, the cable network used to run a program called Kids in the Hall. It was a comedy sketch show, a lesser known version of Saturday Night Live, that was written and executed by a group of five Canadian comics.

Featuring Dave Foley, Bruce McCulloch, Kevin McDonald, Mark McKinney and Scott Thompson, the group achieved enough notoriety to eventually put out a 1996 feature film, Brain Candy, which became a cult classic.

They were all young comedians back in the 1980s, but they’re not exactly kids anymore, all in their late fifties and sixties now. And they’re all still practicing the art of comedy, a difficult achievement in a mercurial industry.

Well, the Hall of Fame has its own version of “Kids in the Hall” – players with the nickname “Kid” or “The Kid.” The baseball version of the group numbers five, just like the comedians, and their staying power as baseball legends is pretty impressive. The group added its fifth member in July, when Ken Griffey, Jr. officially became a member of the Hall of Fame. Griffey joins established members Gary Carter, Robin Yount, Ted Williams, and Charles “Kid” Nichols, all of whom share the nickname with the 2016 inductee.

That brings up the inevitable question: Why is “Kid” such a popular nickname among ballplayers in general, and Hall of Famers more specifically? Well, it only makes sense that a game that favors the youth would produce such a moniker. Most players make the major leagues in their twenties, which is an age associated with young adulthood. It’s only natural for fans, particularly older fans, to refer to such ballplayers as kids. And when a player comes around, one who looks particularly young, or plays the game with such youthful enthusiasm, the Kid nickname will soon follow.

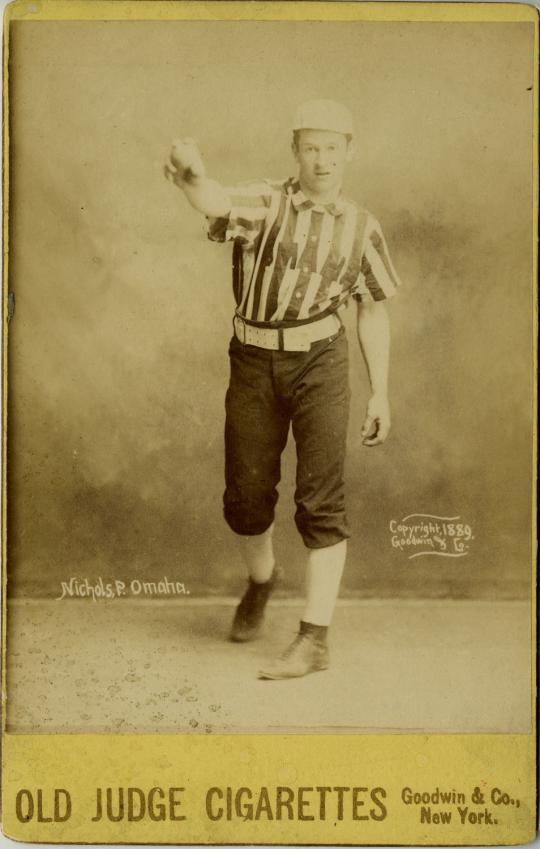

Let’s begin with Nichols, a masterful pitcher for the Boston Beaneaters who starred near the turn of the 20th century and won 360 games. Of all the “kids” in the Hall, he has been enshrined in Cooperstown longer than all of them, having earned induction in 1949. Nichols picked up his nickname early in his career, while he was still pitching in the minor leagues. Shortly after he joined the Kansas City Cowboys of the Western League, Nichols’ teammates apparently mistook the youngster for the team bat boy. That was understandable, given that the rail-thin Nichols weighed only 135 pounds while standing 5-foot-10. Nichols would pitch far better than a typical bat boy, winning 18 of 30 starts for the Cowboys in 1887.

Over the course of his career, Nichols would put on about 40 pounds. But the nickname of Kid stuck; in fact, it essentially replaced his given first name of Charles. When the Hall of Fame issued his plaque in 1949, it put his nickname in parentheses, but in a prominent place, right between “Charles” and “Nichols.” To this day, fans refer to the Hall of Fame right-hander as Kid Nichols and not Charles.

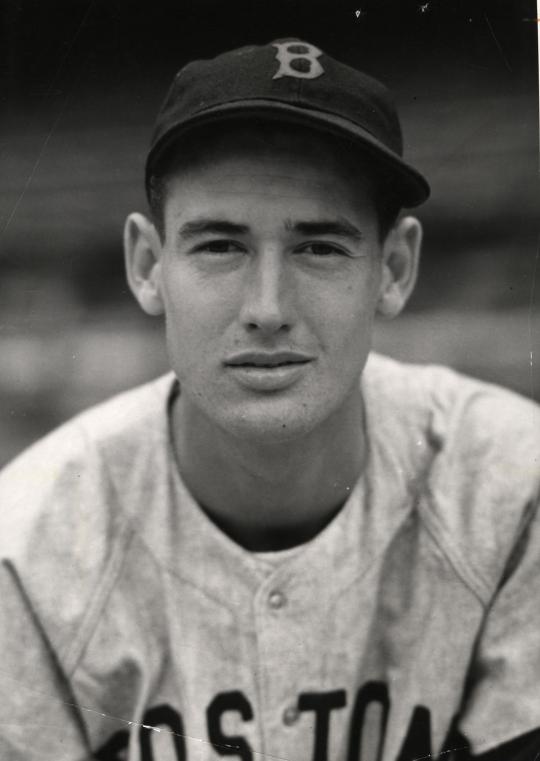

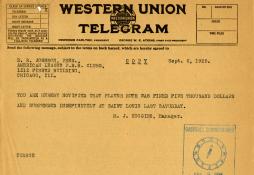

Like Nichols, Ted Williams picked up his nickname early in his professional career, but not until he attended his first Spring Training. The year was 1938; a huge flood in California resulted in the cancellation of all railroad activity, including Williams’ cross-country train from San Diego to Sarasota, Fla. Williams had to borrow $200 from a bank just to complete the trek via car. Arriving 10 days late, Williams finally made his way into the Red Sox’ clubhouse. Noticing the rail-thin youngster, Red Sox equipment manager Johnny Orlando proclaimed, “The kid has arrived.”

Not only did the nickname stick with Williams for the remainder of his career, but Orlando himself continued to call Williams “Kid” for the next 20 years.

Williams had other nicknames, too, like “The Splendid Splinter” and “Teddy Ballgame,” both of which became common ways to refer to the Hall of Fame batsman. It’s interesting to note that when acclaimed author Ben Bradlee published his definitive biography of Williams in 2013, he titled it The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams.

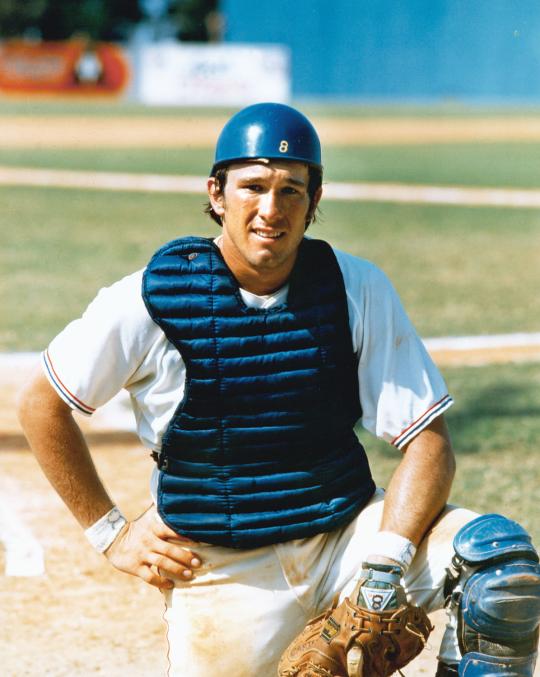

As with Williams, Carter earned the moniker of Kid during his first Spring Training. Reporting to the Montreal Expos’ camp in 1973, Carter wanted to make a good impression, so he put out maximum effort, both in running sprints and hitting the ball. A few of his Expos teammates noticed his behavior. “Tim Foli, Ken Singleton, and Mike Jorgensen started calling me ‘Kid’ because I was trying to win every sprint,” Carter told the Associated Press. “I was trying to hit every pitch out of the park.”

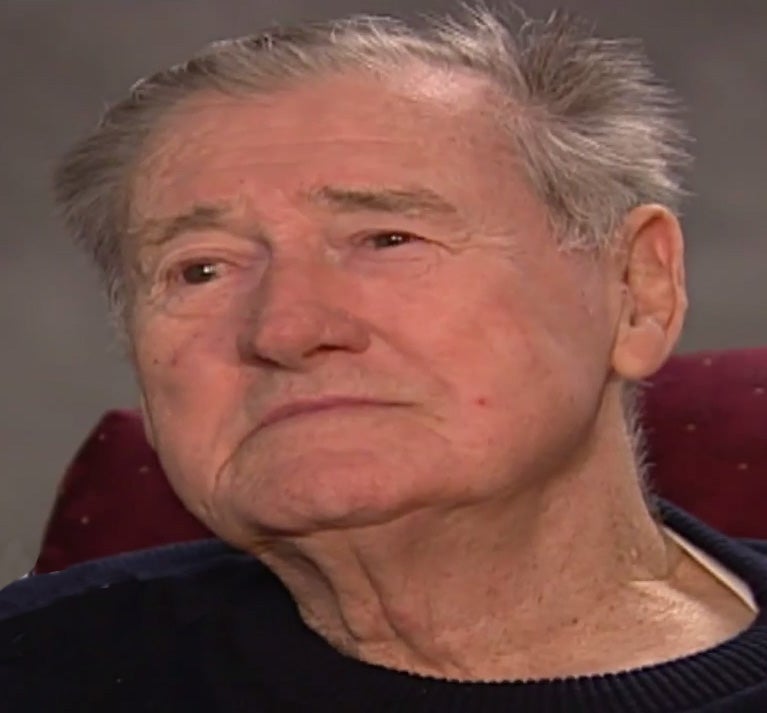

The nickname of The Kid fit Carter perfectly, given his genuinely boyish enthusiasm and his constant hustle. Even as he aged, Carter continued to play the game hard and with gusto, giving no one any reason to alter his nickname. He would remain The Kid until the end, passing away in 2012 at the too-youthful age of 57.

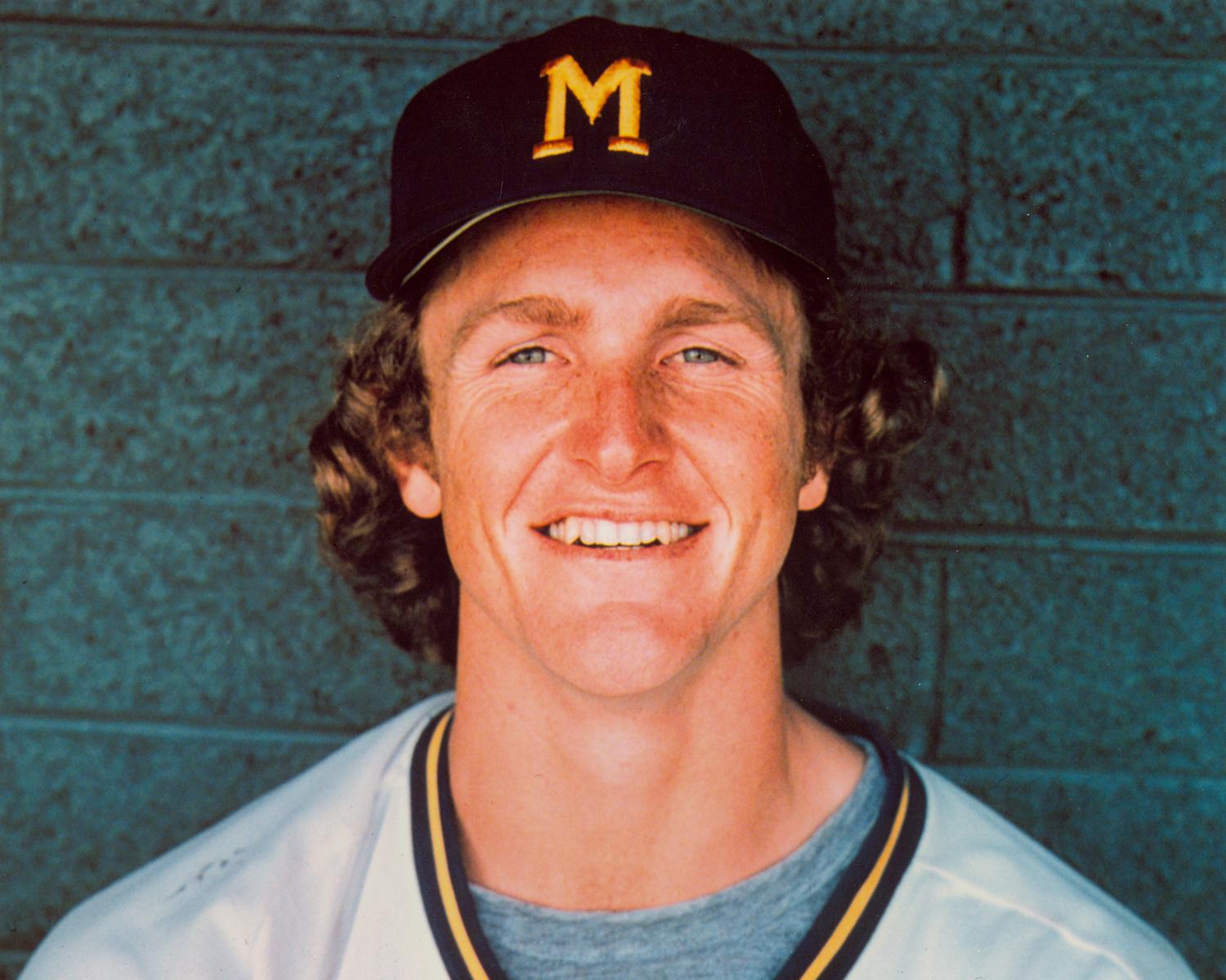

Of all the kid Hall of Famers, the one that perhaps makes the most sense is Robin Yount. On April 4, 1975, Yount made his major league debut for the Milwaukee Brewers – at the age of 18. Less than three years older than the youngest player ever, Cincinnati’s Joe Nuxhall, Yount became one of a handful of major leaguers to start his career as a teenager.

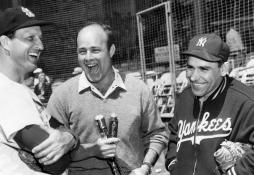

Bob Uecker, the beloved broadcaster and baseball’s unofficial King of Comedy, dubbed Yount The Kid. Even in 1982, when Yount turned 26, won the American League MVP, and led the Brewers to the pennant, he remained The Kid, still a favorite label coming from members of the Milwaukee media.

That brings us to Griffey, Class of 2016. At various times, he has been called “Junior” or even “The Natural.” But he is also The Kid, a fitting nickname for a player who made his debut at the age of 19, when he still looked young enough to be a sophomore in high school. The name also stemmed from his family heritage. Griffey joined the Seattle Mariners in 1989, at a time when his father, Ken Griffey, Sr., was still playing for the Cincinnati Reds. The name of The Kid became a way to distinguish the talented son from the accomplished father.

With the addition of the younger Griffey, the ranks of kids in the Hall has swelled to five. Three of them are gone now, while the other two are a combined 106 years old. They are kids no more.

Yet, in a game that is always served by youth, each one of them remains The Kid in a special way.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame