- Home

- Our Stories

- Sound on Paper

Sound on Paper

“The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”

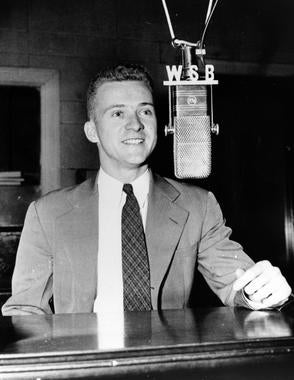

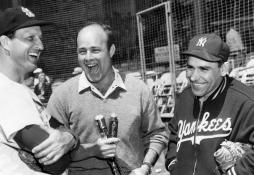

Russ Hodges’ iconic call of Bobby Thomson’s iconic home run is perhaps the most famous sports broadcast in American history. And though Hodges and his broadcaster partner that day Ernie Harwell are now gone, the written history remains forever at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown.

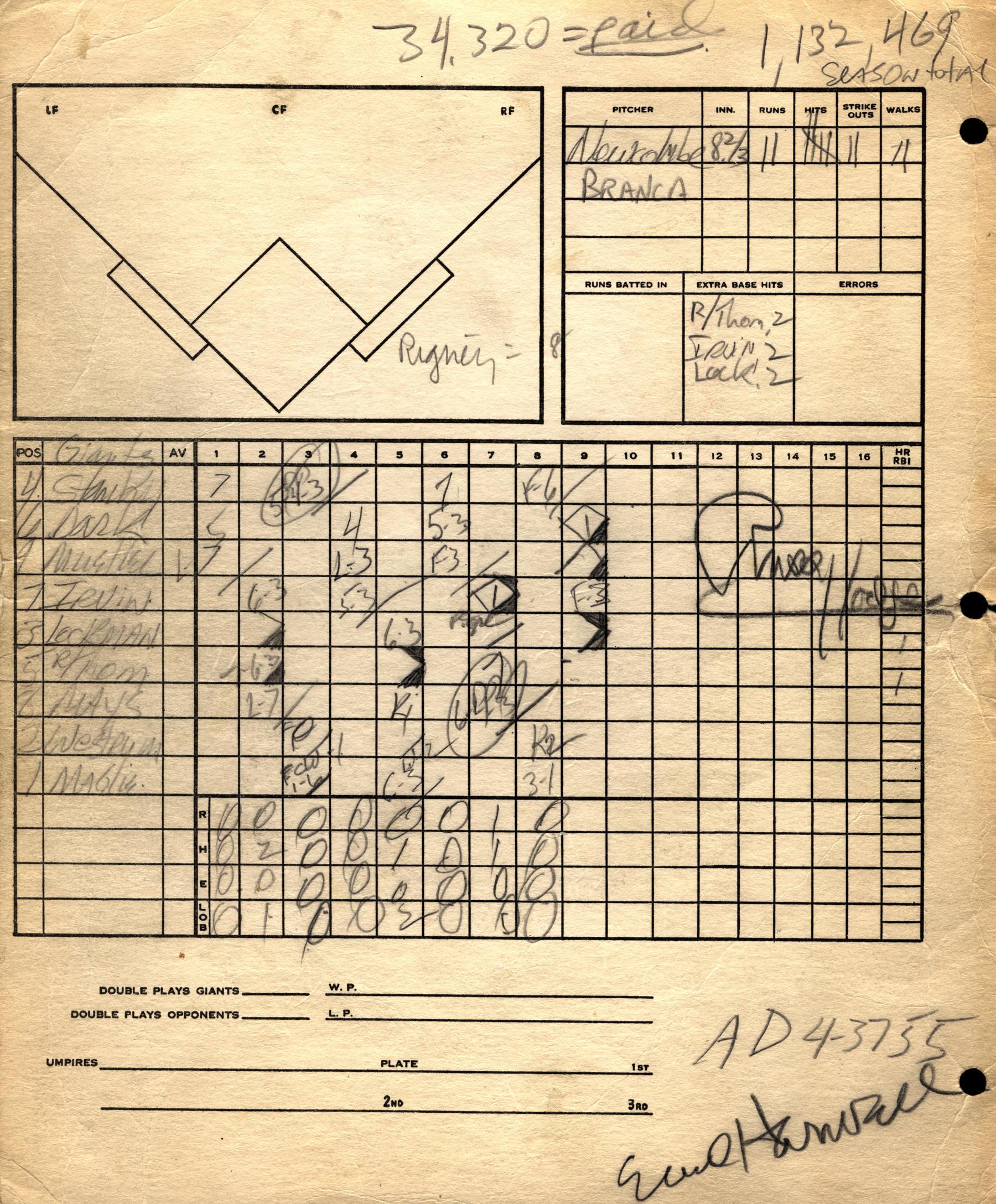

The scorecard, signed by Hodges and Harwell following the Giants’ victory over the Dodgers in the 1951 National League playoff, was donated to the Museum in 1970 by John V. Halk, a New York City police detective on Polo Grounds duty that day.

Actually, it was the Dodgers who tied the Giants in 1951, as the Giants had pulled ahead on the final day of the season, putting themselves in first place and ensuring at least a tie for the pennant. The Dodgers won a dramatic 14-inning game in Philadelphia to force the three-game playoff, as Jackie Robinson made a rally-killing diving catch in the 12th inning, and homered in the 14th to ice the game.

The scorecard not only serves as a primary source concerning the game itself, but also evokes the images and sounds of the day that Thomson hit “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” It remains a portal into the events of Oct. 3, 1951, when the Giants completed the herculean task of erasing a thirteen-and-a-half game Dodgers lead to advance to the World Series.

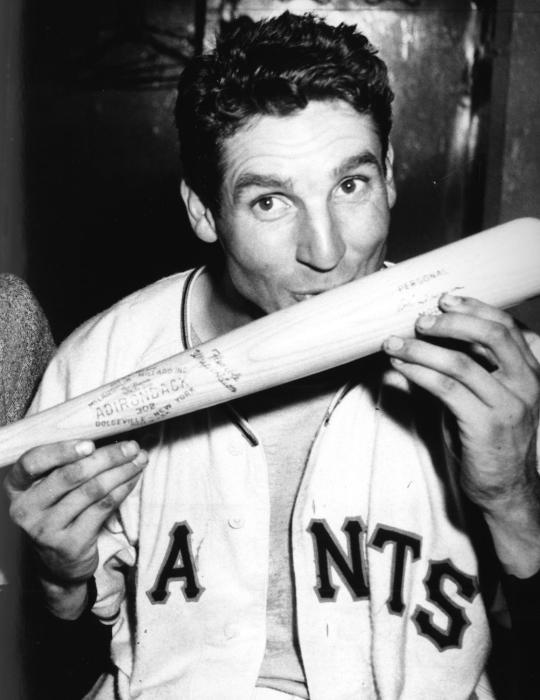

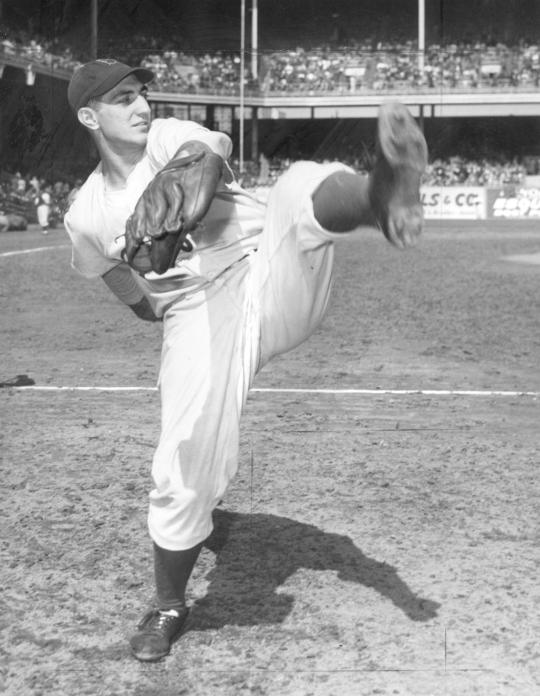

The next day at Ebbets Field, the playoff series began, and the Giants beat the presumably tired Dodgers and Ralph Branca, 3-1 on the strength of a two-run homer by Bobby Thomson, who belted eight of his 32 homers that season against Brooklyn.

The Series moved to the Polo Grounds the next day, and the Dodgers came roaring back, blanking the Giants 10-0. The great battle between the great rivals would go to a final, winner-take all-game.

Hodges and Harwell, the Giants’ broadcast team who would eventually win Ford C. Frick Awards in 1980 and 1981, respectively, were ready for the big game, each in their different ways. Hodges, for his part, was feeling terrible, as he remembered in his 1963 book, “My Giants.” As the Giants – following the final scheduled regular-season game – rode the train home from Boston, where the weather had been cold and chilly, he got on the train’s newfangled phone, and called the office, where they were monitoring the final Dodger game in Philadelphia. It was hard to hear over the train wheels, and Hodges was shouting a narration of the game to all the Giants players.

The weather, the shouting, and the excitement of the first two games, combined with lack of sleep, had given him “a wicked cold.” The broadcaster, who would shortly issue the most famous call in history, wrote: “I was up gargling most of the night, and just to make sure I hadn’t lost my voice, I kept talking into an imaginary microphone at home, which only made my throat worse. I had trouble breathing, my nose was running, and I was sure I had a fever.”

Harwell was thinking philosophically as he drove in from his home in Larchmont: “I felt a little sorry for my Giant broadcasting partner that day. Ole’ Russ is going to be stuck on the radio, there were five radio broadcasts and I was gonna’ be on coast-to-coast TV and I thought that I had the plum assignment.” The two men alternated days in the first coast-to-coast televised sports broadcast – Harwell had games one and three.

“Well, as you remember it turned out quite differently,” Harwell remembered in his 1981 Frick Award acceptance speech. “Russ Hodges’ record became the most famous sports broadcast of all time, television, no instant replay, no recordings in those days, and only Mrs. Harwell knows that I did the telecast of Bobby Thomson’s home run.”

Harwell’s television description of the home run was as spare as Hodges’ radio call was pandemonium: “‘Thomson swings… it’s gone.’ The words were out of my mouth and I couldn’t take them back. Now I saw Andy Pafko leaning back against the wall and I had this horrible thought that I had reacted too soon…” he remembered in the book “Voices of Sport.”

Ironically, in our video age, Hodges’ manic radio description is often played over the television footage of the home run. Harwell, meanwhile, didn’t speak for several minutes. “I let the picture tell the story,” he remembered.

Harwell is correct that no one was recording television broadcasts at the time. He recalled that a kinescope recording would have been around $300 dollars and that was deemed too expensive. But a similar ethos prevailed on radio. Though there were five broadcasts emanating from the Polo Grounds that day, few were known to be taped. We know the greatest broadcasting call in sports history because of Giants fan Lawrence Goldberg and his mother, Sylvia.

Goldberg was listening to the game, but as the tension mounted, he had to leave home and get to work, so he asked his mother to hit ‘record” on his reel-to-reel tape recorder when the game entered the bottom of the ninth. On the 50th anniversary of the game, he told The New York Times Richard Sandomir about his fateful decision: “I knew I wouldn’t be able to listen to the broadcast and I knew something was going to happen. It was the third game of the playoffs. That kind of game had to be climactic.”

The taping incident is a lesson for historians in the use and interpretation of primary sources. Hodges would often recall that Goldberg was a Dodger fan, who wanted to have a recording of the game’s end in order to gloat over his Giant fan friends. Goldberg, however, the more primary source on his own urge to tape, told Sandomir that he was a lifelong Giants fan.

On Oct. 4, Goldberg wrote to Hodges and asked him if he had a tape of the call and offered to lend his tape if needed. Hodges borrowed the tape and made records of it as a Christmas gift for friends – Note: If anyone reading this has one of those records, the Hall would love to add it to our collection. Later, Chesterfield Cigarettes, mentioned in the half inning and one of the broadcast’s sponsors, asked to make copies for marketing purposes. Goldberg was paid $100 and given access to Chesterfield’s box at the Polo Grounds for the 1952 season. Hodges himself sent Goldberg a nice thank you gift – a reel of blank tape – probably not inexpensive or easy to come by in those days.

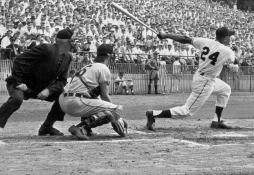

A half inning before Hodges’ call, the moment did not seem ripe for history. The Giants came to bat in the bottom of the ninth trailing 4-1 against Don Newcombe, who Hodges recalled “seemed to be getting stronger instead of weaker.” Alvin Dark led off and beat out an infield hit, going to third on Don Mueller’s single to right. Monte Irvin popped up for the first out. Whitey Lockman doubled to the left field corner, scoring Dark and sending Mueller to third – he injured his ankle sliding and was replaced by Clint Hartung. At that point, Ralph Branca came in for Newcombe. With future Hall of Famer Willie Mays on deck and first base open, the Dodgers pitched to Thomson and Branca began with strike one. On an 0-1 count, Thomson swung and Hodges took over:

“Branca throws…There’s a long fly… it’s gonna be, I believe… The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! Bobby hit it into the lower deck of the left-field stands… The Giants win the pennant and they’re going crazy… I don’t believe it… I don’t believe it… I will not believe it… Bobby Thomson hit a line drive into the lower deck of the left-field stands and the place is going crazy! Oh, Oh!... and they’re picking up Bobby Thomson and carrying him off the field…”

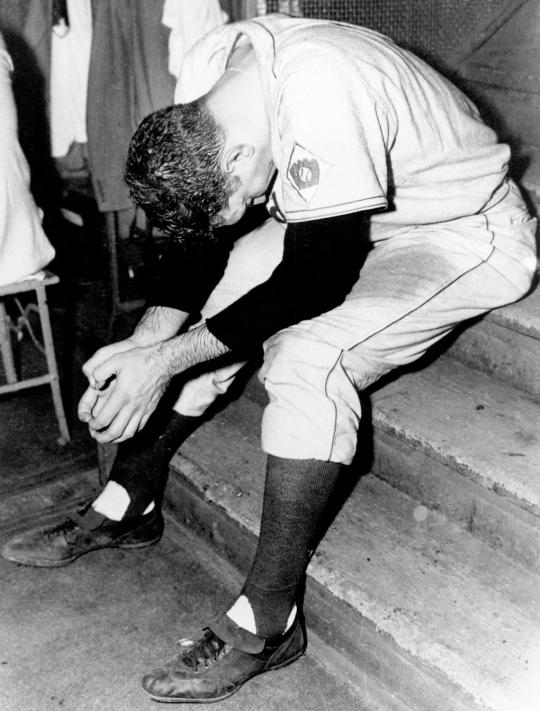

Take a close look at Thomson’s square on Hodges’ scorecard. There is a pencil mark where he began to record the home run, but was unable to complete it, probably due to the emotion of the moment.

Tim Wiles was the director of research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum