- Home

- Our Stories

- Clemente’s lone minor league season put him on a path to Pittsburgh

Clemente’s lone minor league season put him on a path to Pittsburgh

It is perhaps the least publicized part of Roberto Clemente’s career in professional baseball. In 1954, Clemente spent his lone season in the minor leagues, playing for the top affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

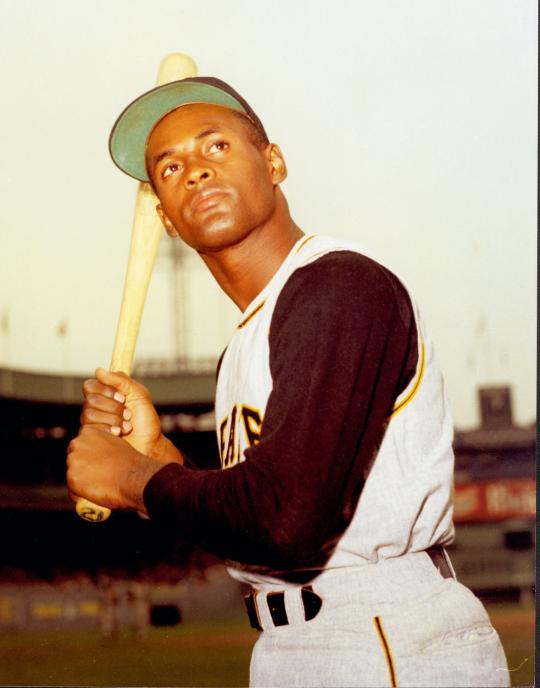

During that season, Clemente’s play drew the attention of another major league team – the one with which he would become so closely associated.

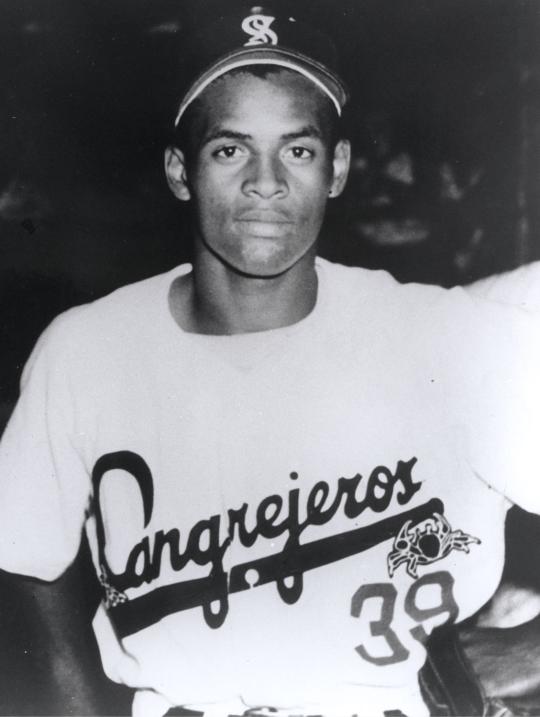

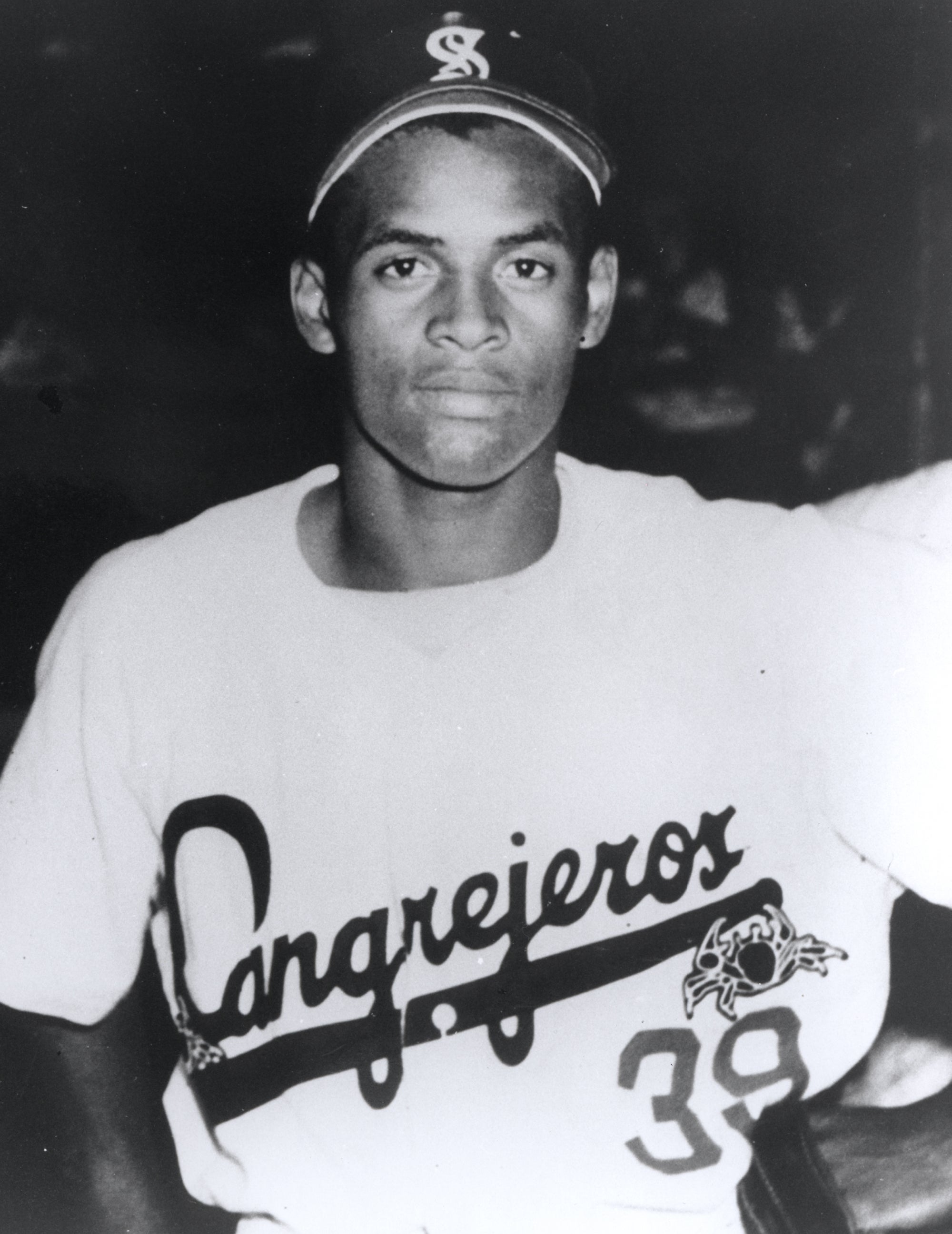

Roberto Clemente’s eye-popping performance with the Santurce Crabbers of the Puerto Rican Winter League in early 1954 had clearly cemented his status as a major league prospect. Several teams showed interest in the young outfielder, including the Milwaukee Braves and the New York Giants.

Not wanting the rival Giants to add Clemente to an outfield that already boasted the talents of a promising Willie Mays and the more established Monte Irvin, the Brooklyn Dodgers upped the ante on the Giants’ bid. The Dodgers offered a salary of $5,000, along with a signing bonus of $10,000. It was the largest bonus that the Dodgers were prepared to dole out since signing Jackie Robinson to a minor league contract in 1945.

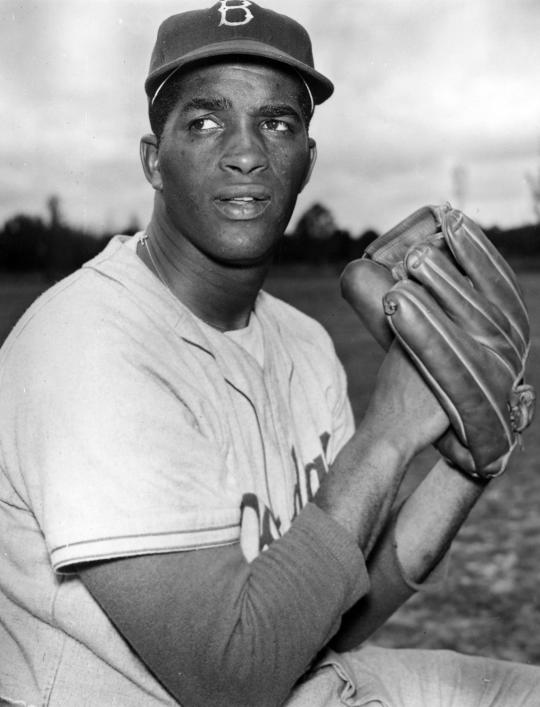

On Feb. 19, 1954, Clemente formally accepted the offer and signed his first contract with the Dodgers. While the Dodgers loved Clemente’s talents, they did not feel that he was ready to play in the major leagues just yet. So during Spring Training they assigned him to the Triple-A Montreal Royals, their top affiliate in the International League.

On the surface, the move made sense, given Clemente’s still raw and unrefined talents, but it created a future problem for the Dodgers. Under the rules in place in 1954, any player receiving a bonus of $4,000 or more who was assigned to the minor leagues would then be subject to a special draft at season’s end. Under the new rule, which would eventually become known as Rule 5, such a player could be taken by another major league franchise at the cost of only $4,000. Al Campanis, working as a winter league manager at the time, warned Dodgers vice president Buzzie Bavasi that he was taking a huge gamble by not putting Clemente on the major league roster for the entirety of the 1954 season.

It did not take long for Clemente’s physical talents to manifest themselves in Montreal. During the opening week of the International League season, Clemente blasted a 400-foot home run at Delorimier Downs, Montreal’s home ballpark. One of Clemente’s teammates with the Royals happened to be right-handed pitcher Joe Black, who had been assigned to Montreal after a rough 1953 season.

“I was impressed,” Black said. “[Clemente] was 18 years old, just turning 19, but he had a lot of desire to play. The thing that amazed me is that sometimes one of his legs would be up in the air [while he was] hitting, and [the ball] would still go out of the ballpark. He was just strong.”

In spite of his power, his bat speed, his strong defensive skills and his remarkable throwing arm, the Royals played Clemente sporadically throughout the spring and summer. Some observers have contended that Royals manager Max Macon was under orders from Brooklyn management to keep Clemente under wraps – in other words, to play him only intermittently as a way of minimizing his talents and hiding him from other teams’ scouts. For his part, Macon always denied that the Dodgers gave him such an order, a stance that he maintained until his death in 1989.

While the extent of the Dodgers’ effort to hide Clemente has been disputed – with some historians contending that the Dodgers made no such concerted effort – there is no dispute that Clemente’s playing time in 1954 resembled that of a part-time player, and not a regular. As a team, the Royals played 154 games, but Clemente made only 87 appearances, accumulating a total of 155 plate appearances despite the fact that he suffered no major injuries. For a player regarded as a top prospect, the amount of playing time was alarmingly low.

No matter the reason for his sporadic playing time, the situation frustrated Clemente, who wanted to play every day. He also faced other problems with the Royals. Still a teenager at the time, Clemente had limited experience with the English language. He also spoke no French, the preferred language of many of Montreal’s fans. Only a few of Roberto’s teammates – Black, Sandy Amoros, and Chico Fernández – spoke Spanish, limiting his ability to communicate with other players.

There were racial problems, too. For the most part, Clemente found fans in Montreal accommodating and accepting of a dark-skinned Latino like himself. He and Fernández were invited to live with a white family in one of Montreal’s French residential neighborhoods. But there was one unsightly incident that did occur outside of Delorimier Downs. One day, Clemente was speaking to a white woman outside of the ballpark; for that, he was angrily chastised by a nearby fan, who advised him that such “behavior” was not acceptable.

On road trips, Clemente endured the Jim Crow segregation of the American South. On his first road trip to Richmond, Va., Clemente discovered that he could not eat in the same restaurant as his white teammates. (No such practice existed in Montreal.) Similarly, he was not allowed to stay in the same hotel with the white players on the Royals.

In spite of such characterizations, Clemente played hard for the Royals. He also flashed his majestic talents, even if the intermittent playing time played havoc with his swing and his timing. Some opposing scouts overlooked Clemente, but there was at least one who did not. He was the astute Clyde Sukeforth, the same man who had once recommended to Branch Rickey that he should sign Jackie Robinson in 1945.

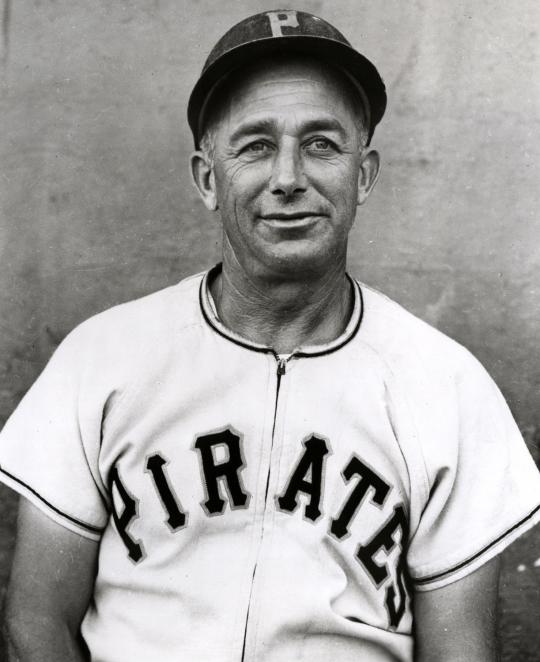

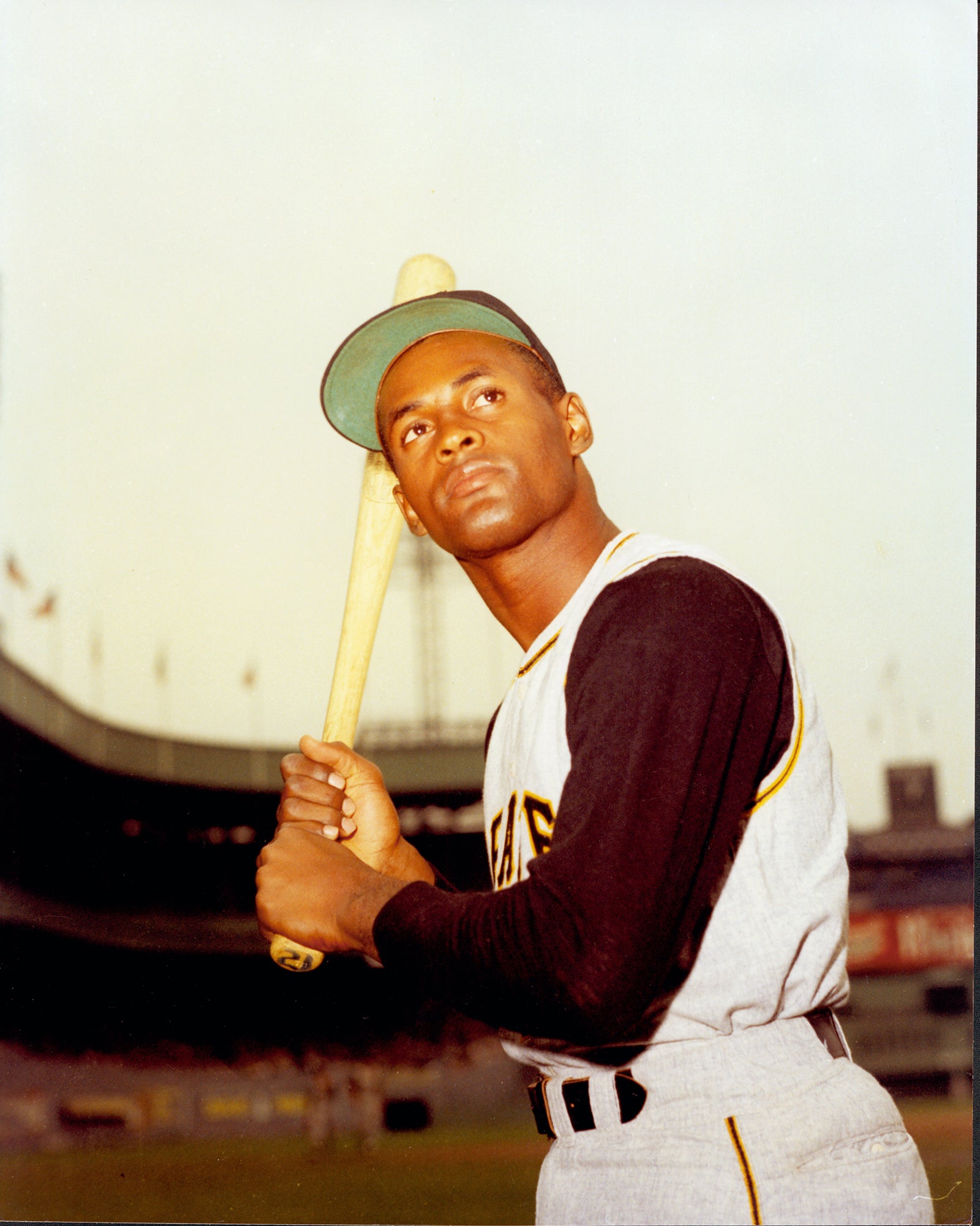

Now heading up baseball operations for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Rickey sent Sukeforth to scout the Royals, ostensibly to take a look at Joe Black, whom the Dodgers were considering in a trade. Black did not pitch that day, but Sukeforth did arrive early to watch batting practice and defensive drills. The veteran coach and scout took notice of the Royals’ right fielder, a young man with a cannonlike throwing arm. Sukeforth stayed to watch the game and saw this same player nearly beat out a routine ground ball to shortstop. The player who could run and throw so well was none other than Clemente.

Prior to his visit to see the Royals, Sukeforth had not heard of Clemente. So Sukeforth started to ask questions of people at the ballpark, hoping to gather information about this young player who had fallen under the radar. “I learned that he was a bonus player,” Sukeforth told the Sporting News, “and would be eligible for the [Rule 5] draft.” With the Pirates headed to a last-place finish in the National League that summer, they would own the first pick in that offseason draft.

After watching Clemente hit with power in batting practice, Sukeforth wrote a letter to Rickey. “I haven’t seen Joe Black [pitch],” Sukeforth wrote, “but I have seen your draft pick.” In no uncertain terms, Sukeforth informed Rickey that Clemente should be the Pirates’ first selection.

As much as Rickey respected Sukeforth and his advice, he wanted a second opinion. He assigned one of his top scouts, Howie Haak, to follow up on Sukeforth’s report and watch Clemente in game action. Haak witnessed Clemente hit two triples and a double. Like others, Haak quickly became convinced that the Dodgers were trying to hide their talented prospect. In delivering his own report to Rickey, Haak confirmed the initial scouting report issued by Sukeforth. Clearly, Clemente was the player the Pirates needed to take in the Rule 5 draft.

That winter, Rickey decided to take a look at Clemente himself during his winter ball season in Puerto Rico. Just like Haak and Sukeforth, Rickey came away impressed with Clemente. He also took time to talk to him during his scouting trip. Rickey found the young prospect polite and respectful.

On Nov. 22, 1954, the Pirates prepared to make the first pick of the draft. Rickey announced the team’s selection: Roberto Clemente. As with any selection in the draft, it cost the Pirates all of $4,000, to be paid to the Dodgers.

Four thousand dollars: That was the grand sum the Pirates paid out. And it represented some of the best money the Pirates ever spent in the long history of their franchise.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and wrote “Roberto Clemente: The Great One”, a biography which was published in 2013