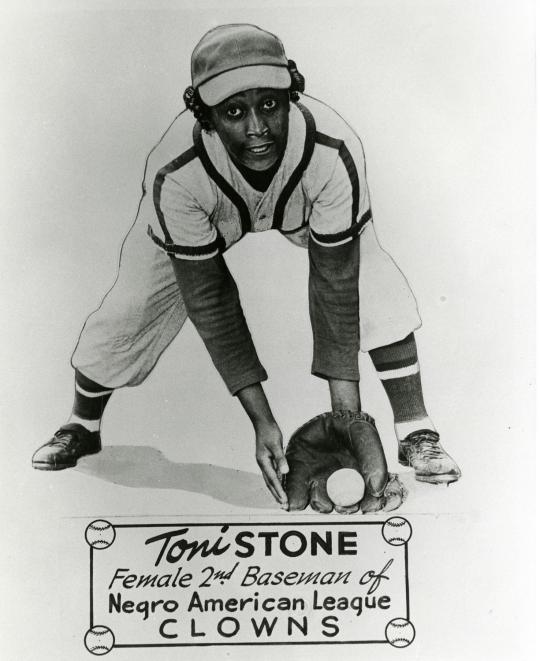

Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and Mamie Johnson blazed a trail for women in the Negro Leagues

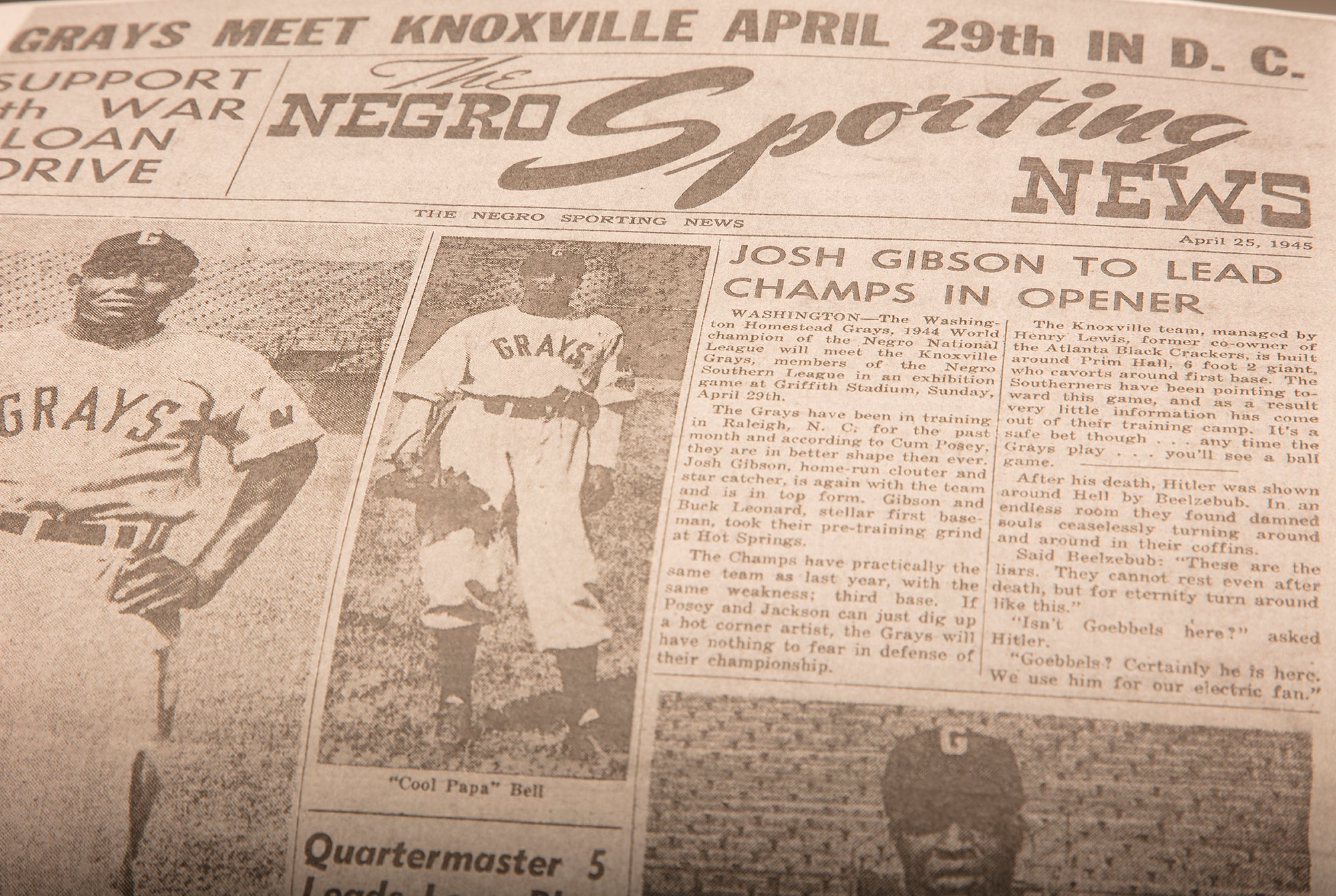

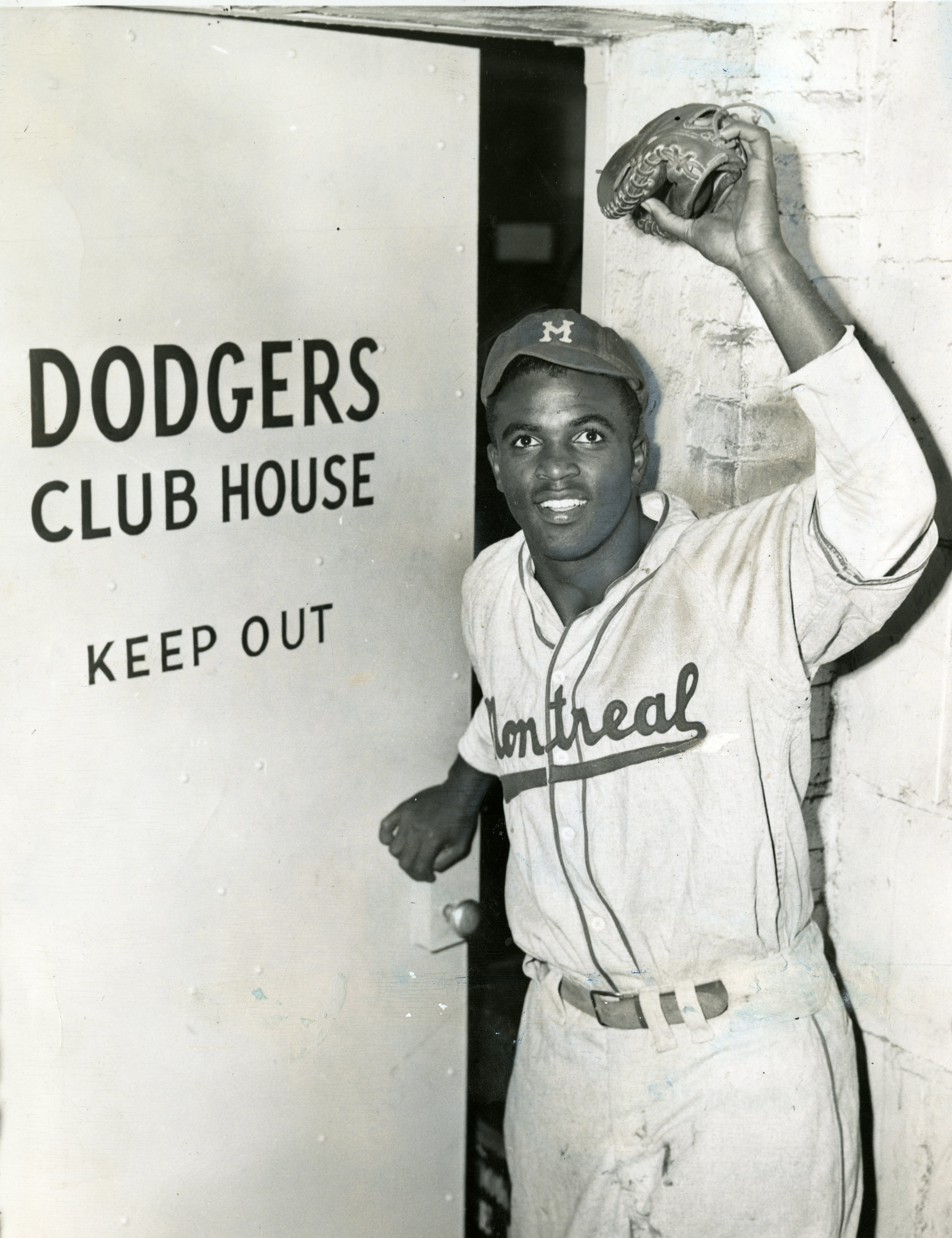

After Jackie Robinson led the exodus of talent out of the Negro Leagues and into the majors – and the fans followed – Syd Pollack, owner of the Indianapolis Clowns, was desperate to resuscitate interest in his team.

The Negro National League had folded in 1948, and by 1953 the Clowns were one of only four teams left in the Negro American League. Pollack, whose promotional hijinks had earned the Clowns a designation as “the Harlem Globetrotters of baseball,” had tried dressing King Tut in a tuxedo and employing a daffy dwarf as sideline entertainers.

But in the ‘50s, Pollack signed three women who had the talent to be more than simply gate attractions.

The first was Toni Stone, whom Pollack signed in 1953. Stone had played hardball with boys since she was a girl in St. Paul, Minn. By 16, she was pitching for a semipro team, the Twin Cities Colored Giants. She played with two more semipro teams, the San Francisco Sea Lions and the New Orleans Creoles, before agreeing to play second base for the Clowns and become the first woman to play in the Negro American League.

Playing on a men’s team presented challenges off the field as well. Stone had to change in the room used by the umpires. On road trips, she often stayed at brothels, a practice that began when the proprietor of the hotel where the team stayed figured she must be a prostitute – when he saw her get off the bus with 28 men – and gave her directions to the nearest brothel. Stone, who could identify with the brothel workers as an outsider, was welcomed by them.

Stone did not play as often as she would have liked, appearing in only about 50 of the 175 games the Clowns played in 1953. After the season, Pollack sold her contract to the Kansas City Monarchs, whom Stone played with in 1954 before retiring. During her two years in the National American League, she had a career batting average estimated to be .243, but at one point in the 1953 season she was batting .364, fourth in the league, right behind Ernie Banks.

Legend has it she rapped a single off Satchel Paige, but the archives don’t corroborate the story. Still, the persistence of those who believe the story – including Martha Ackerman, author of the Stone biography “Curveball” – bears testament to Stone’s skills, making such a feat plausible.

Yet the Afro-American also recognized Morgan’s unqualified baseball ability. In an account of a May game, it described how Morgan "electrified over 6,000 fans…when she went far to her right to make a sensational stop, flipped to shortstop Bill Holder and started a lightning double play against the Birmingham Barons."

The New York Amsterdam News validated the talents and temperament of Stone, Morgan and Mamie Johnson (whom Pollack also signed in 1954) when the Clowns played the Monarchs in a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium: “The girls take a back seat to no one on the field.”

Morgan played just one season in the National American League, splitting time at second base with Ray Neiland, batting third and posting about a .300 average.

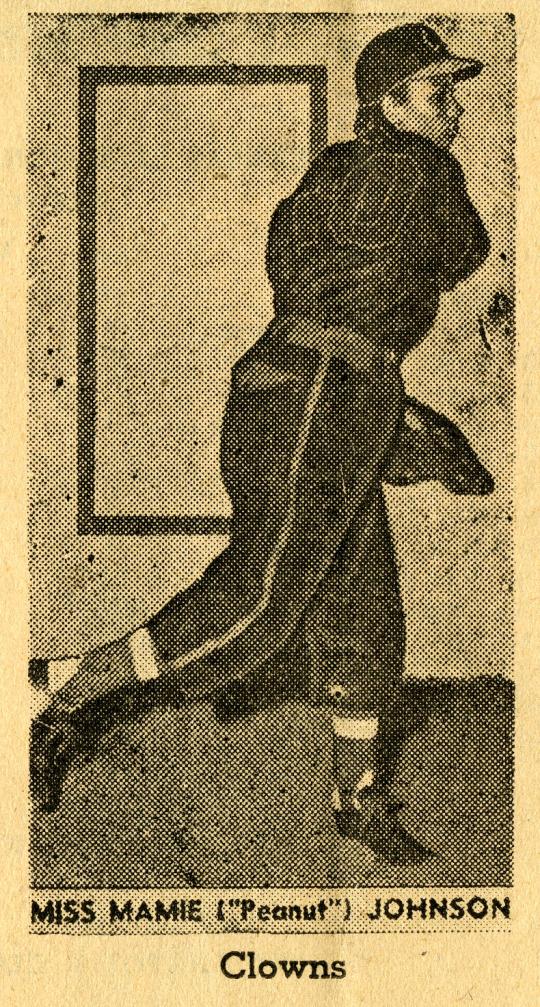

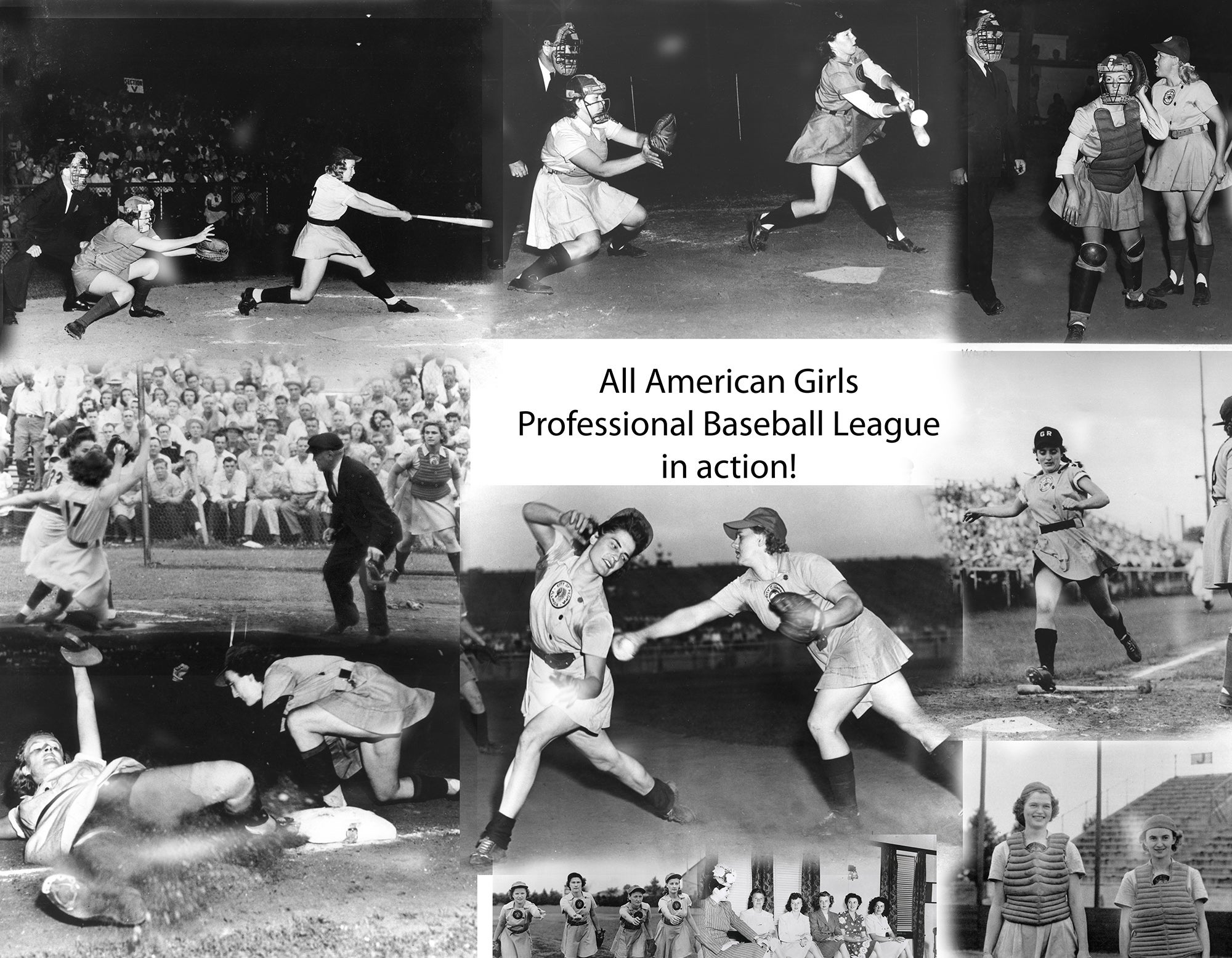

Good story, but newspaper accounts of her signing with the Clowns identify her already as Mamie “Peanut” Johnson. Like Morgan, she was an excellent all-around athlete born in South Carolina who reportedly was the first girl at her Long Branch High School (New Jersey) to play football, basketball and baseball. In 1953, the 18-year-old Johnson went to Washington for a tryout with the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

She and her friend, also African American, hadn’t realized that the AAGPBL remained all-white. After being ignored for 15 minutes, Johnson turned to her friend and said, “We better go. I don’t think we’re wanted here.”

Johnson found a men’s semipro team that did want her, which is where a scout for the Clowns saw her and recommended her to Pollack. The men were skeptical at first about this pint-sized pitcher, but she earned their respect with her talent. “After you prove yourself as to what you came there for, then you don't have any problem out of them, either,” she said in a 2003 interview with National Public Radio.

Johnson played into 1955 with the team but left before finishing the season, saying she wanted to spend more time with her young son. By her own account, Johnson went 33-8 during her time with the Clowns, though Negro League historians question the validity of that record (the record books are incomplete on the subject).

Not disputed, though, is the fact that she was the first female pitcher in professional baseball and one of three courageous women to play in the Negro American League.

Though Stone, Morgan and Johnson faced resistance during their playing days, the years have been kind to their memory. Stone was inducted into the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1985, and St. Paul named a city baseball field after her. Morgan was inducted into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame in 1995. And in a ceremonial MLB draft of living Negro League players in 2008, Johnson was selected by the Washington Nationals.

Long after they retired, these women, who challenged the way society viewed their gender, have earned the respect they deserved.

John Rosengren is a freelance writer from Minneapolis, Minn.