- Home

- Our Stories

- Black newspapers preserved Negro Leagues history

Black newspapers preserved Negro Leagues history

While growing up in Jacksonville, Fla., in the 1910s and ’20s, Buck O’Neil couldn’t wait for Monday afternoons.

That’s when the bundle of newspapers would arrive in the mail, and he and his friends would congregate to read about their baseball heroes in historically Black publications, such as the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier and New York Amsterdam News.

“My father subscribed to those weekly papers, mostly so I could learn about the Negro baseball teams,’’ O’Neil wrote in his 1996 autobiography, "I Was Right On Time."

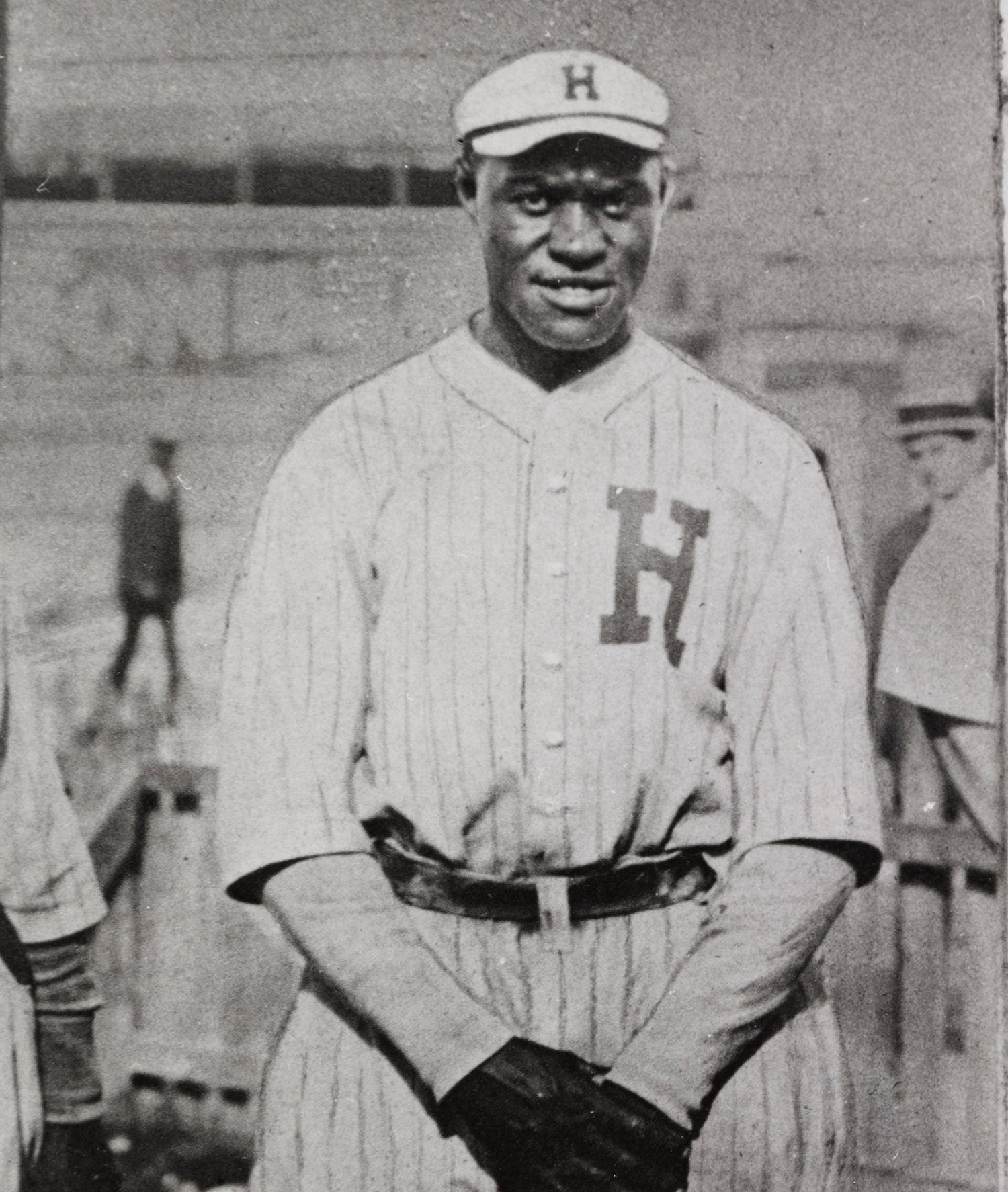

“When the mail arrived on Monday, all the kids were at my house, reading about Dick Lundy, who was from Jacksonville and was a great shortstop with the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City. Or the legendary John Henry Lloyd, another fantastic shortstop from Palatka, Fla.”

Those stories of local African Americans making good jumped off the pages. They provided O’Neil and his friends with role models – and gave them hope in the Jim Crow South.

“We’d read about these guys until we wore the paper out,’’ O’Neil recalled. “Then, we’d go out and make believe we were Pop Lloyd and Dick Lundy until it got too dark to see the ball.”

In that era long before television, widespread radio availability and the internet, newspapers were the dominant disseminators of news and information, and baseball was the undisputed sports king. The Black press played an integral role not only in boosting the collective spirits of African Americans, but also in writing the rough drafts of Negro League baseball history.

The Black newspapers and baseball franchises would benefit from a symbiotic relationship that grew more complex over time, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s when pioneering baseball writers Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy led the charge toward integration, on and off the diamond.

“The Negro Leagues would not have existed without the Black press – it’s as simple as that,’’ said Leslie Heaphy, a Kent State University history professor and one of the nation’s foremost experts on Black baseball. “The leagues benefitted enormously from the publicity generated during a time when the mainstream white press ignored virtually anything of consequence to African Americans. And there’s no doubt that the papers benefitted, too. Their coverage of Negro League baseball, which was a huge source of pride to their readers, sold newspapers.’’

Larry Lester, a driving force behind the building of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, said the Black press’ coverage of the Negro Leagues provided one of the few avenues of information available to Black readers.

“The Black press was the voice of the voiceless,’’ Lester said. “It was essential in getting out the message of Black achievement, Black accomplishment. Its coverage of the Negro Leagues, in particular, had a huge impact on the collective psyche of the Black community. And the Black baseball writers, in addition to pushing for integration, played a big part in the creation of heroes and role models, and reminding us that we weren’t inferior because of the color of our skin.”

Lester cited columns and editorials putting Black stars on equal footing with white stars.

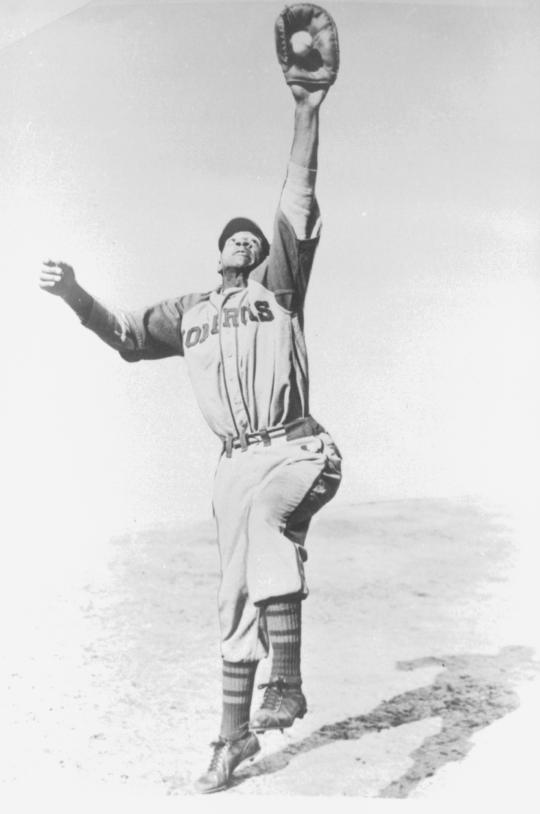

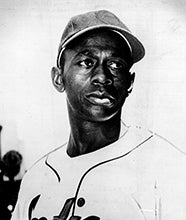

Like thousands of fans in the earliest days of the 20th century, Buck O'Neil followed Black baseball stars through the newspapers that documented the Negro Leagues. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

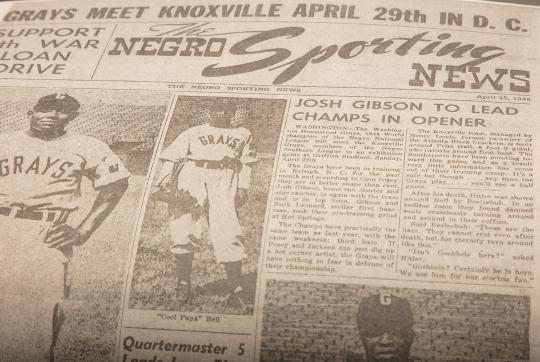

“The Black newspapers ran editorials saying, “Hey, Spot Poles is just as great as Ty Cobb,” or “Josh Gibson is just as great as Babe Ruth,” ’’ said Lester, an accomplished author whose work with the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s “Out of the Shadows” project unearthed huge amounts of data about the Negro Leagues. “Those comparisons to the white superstars had meaning to Black readers. Every minority wants to know how it measures up to the majority, and in the estimation of the Black baseball writers of those times, Black ballplayers measured up quite well.”

Interestingly, white baseball writers would never compare white major leaguers to Negro Leaguers. In the 1930s and ’40s, no one in the mainstream press was writing that Babe Ruth was the white Josh Gibson. Not surprisingly, white and Black writers covered exhibition games between white and Black teams differently.

“If Babe Ruth went 0-for-3, the white papers might write that Babe had to be under the weather or that the white players didn’t care as much about the outcome as the Black players did,’’ Lester says. “Meanwhile, the Black writers might celebrate just how good the pitcher who fanned the Babe three times was. It’s interesting from a historian’s perspective to read the contrasting points of view.”

Negro League baseball was one of the most successful minority-run businesses of the 1920s, ’30s and ‘40s. And that success resulted in several of the owners being written about almost as much as and as glowingly as star players like Gibson, Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell.

Slim newspaper budgets and once-a-week, rather than daily publication schedules, left many Negro League games unstaffed, resulting in incomplete and inaccurate statistics. But the fuzzy numbers did not prevent the Black press from giving teams exposure extending far beyond their hometowns. Papers like the Courier, Defender and Amsterdam News developed national circulations among Black readers.

“With a conglomeration of hyperbole, tongue-in-cheek humor, and endless similes, sportswriters such as Fay Young, Wendell Smith, Ric Roberts, and A.D. Williams made the Negro Leaguers heroes across the nation,’’ author Janet Bruce wrote in her 1985 book, "The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball."

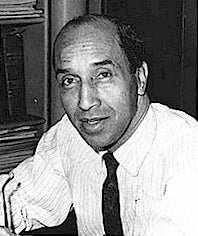

Coverage, though, went beyond myth-making and hero-worship. Injustices were regularly reported – and attacked – in scathing commentaries. So, too, was the push for integration. As far back as the late 1860s, when the all-Black Philadelphia Pythians were denied entry into the National Association of Base Ball Players, there were stories in the Black press about the need for integration. Columns and editorials advocating the abolishment of baseball segregation would run intermittently in the ensuing years and decades, but the big push wouldn’t come until the 1940s, and it would be led by Smith and Lacy. “There were others who contributed to the charge, but, to me, Smith and Lacy were the godfathers of Black sportswriters,’’ Lester said. “They were an essential part of the great experiment called Jackie Robinson.”

Sam Lacy, center, poses with Hall of Famers Satchel Paige (left), Monte Irvin (right) and Roy Campanella (lower right) in Cooperstown. Lacy was presented with the 1997 J.G. Taylor Spink Award for meritorious contributions to baseball writing. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Their historical impact did not go forgotten. In 1993, Smith became the first Black writer to receive the J.G. Taylor Spink Award from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Four years later, Lacy would join him in Cooperstown in the Museum’s Scribes and Mikemen exhibit, which honors every Spink Award winner.

The advocacy journalism of Smith, Lacy and other Black writers would ultimately lead to the demise of the Negro Leagues. Robinson’s shattering of the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers opened the doors for Black baseball stars to join the heretofore segregated Major Leagues. The loss of those outstanding ballplayers, coupled with scaled-back coverage by the Black press, proved to be a death knell for the Negro Leagues by the mid-1950s.

“Instead of devoting the lion’s share of their coverage to Negro League stars, Smith and Lacy were traveling with Jackie, even in 1946 when he was in the minors (with the Montreal Royals),’’ Heaphy said. “This trend would continue when other Black stars, like Roy Campanella and Willie Mays and Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks, joined the majors. They became the stories readers of the historically Black press wanted to read about.”

Negro League owners found themselves in an impossible spot. They realized they couldn’t argue against the integration that ultimately would put them out of business.

“Owners like Effa Manley tried to bargain with the Black press,’’ Heaphy said. “She correctly pointed out that not every Negro Leaguer was going to make the white major leagues. In fact, only a small percentage of them would. So, she pled with Black sportswriters to keep covering the Negro Leagues, to not turn their backs on them. But they were in business to sell papers, and so they turned their attention to the Black players in the major leagues.”

Over time, many of the historically Black newspapers would fold, too. But their impact, like the impact of the Negro Leagues, continues to be felt long after they ceased publication.

“Those stories provided us with a treasure trove,’’ Lester said. “So much of the history of Black baseball is based on those newspapers accounts, and it becomes even more essential as more and more of the people who played in the Negro Leagues or witnessed the Negro Leagues die off.”

Adds Heaphy: “Those newspaper accounts are the primary foundation on which Negro League history is based.”

Best-selling author Scott Pitoniak resides in Penfield, N.Y.