- Home

- Our Stories

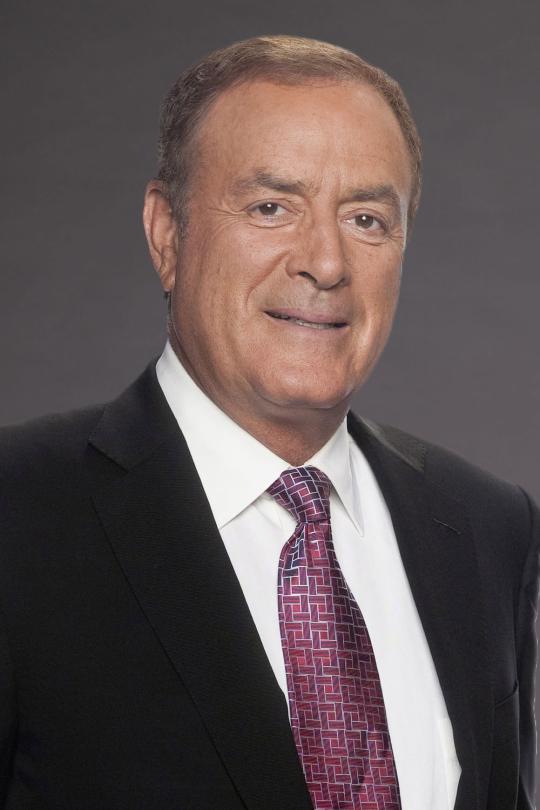

- Baseball inspired Al Michaels

Baseball inspired Al Michaels

Al Michaels’ broadcasting talent has brought him national acclaim in his more than six decades of broadcasting sports from around the world.

But his unique skill behind a microphone with a baseball diamond laid out in front of him will bring him to the Village of Cooperstown in the summer – because he’s now been recognized with the profession’s most prestigious honor.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Michaels was named the 2021 winner of the Ford C. Frick Award on Wednesday, Dec. 9, an honor presented annually by the National Baseball Hall of Fame to a broadcaster “for major contributions to the game of baseball.”

They’re the voices of summer, wordsmiths who made the game of baseball come alive on radio and television, and the best of the best are forever honored in Cooperstown.

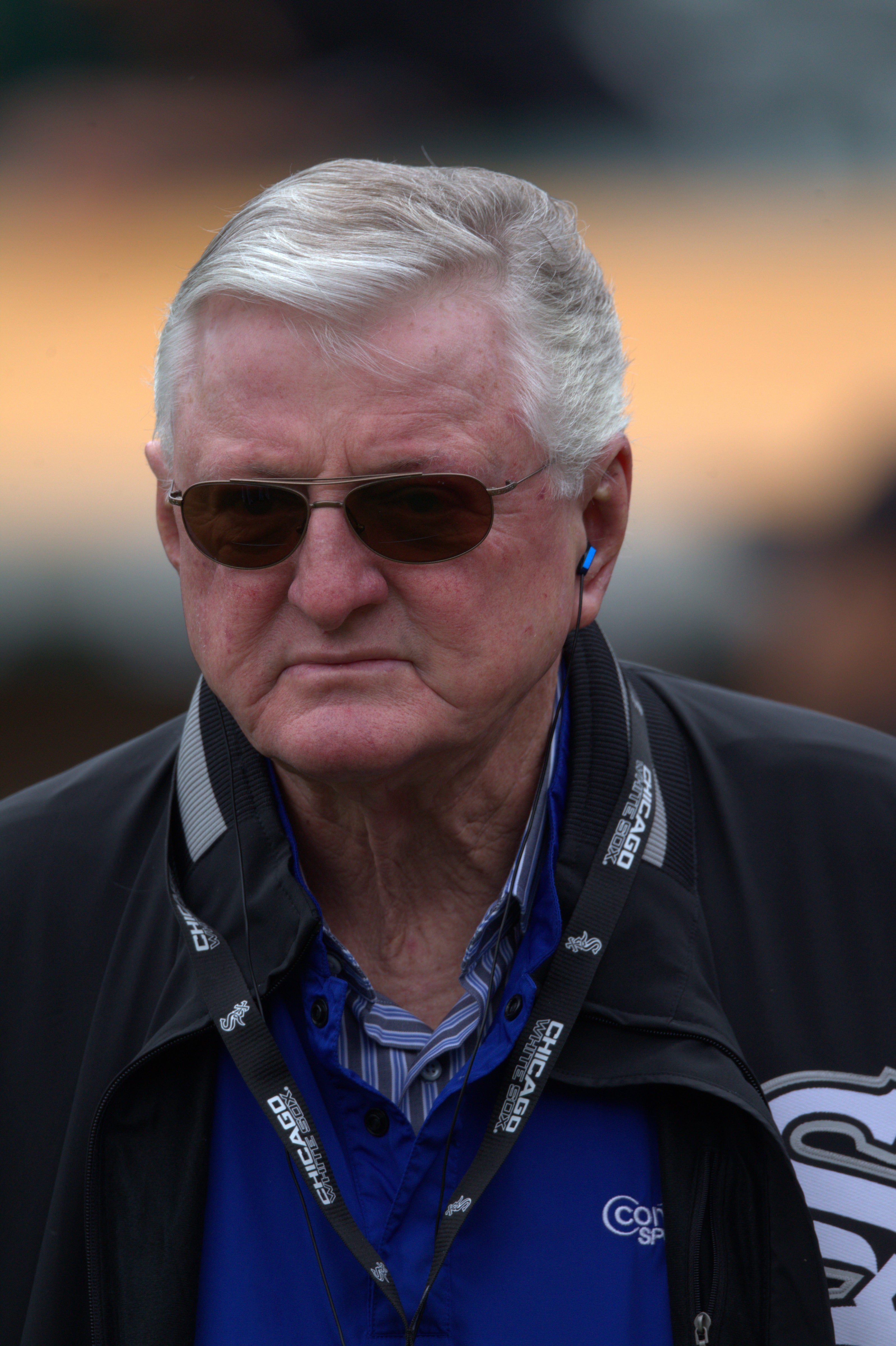

Michaels, the Frick Award’s 45th recipient, will be honored at Induction Weekend 2021 in Cooperstown during the July 24 Awards Presentation. Both Michaels and Ken “Hawk” Harrelson, the 2020 Frick Award winner, will be honored during Induction Weekend following the cancellation of the 2020 Induction Ceremony.

“I thought it was fantastic,” said Michaels a few hours after the Frick Award results were announced. “It was a wonderful feeling.”

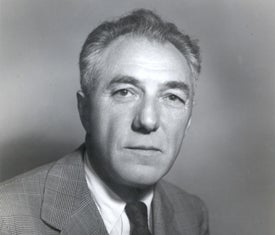

The Frick Award has been presented annually by the Hall of Fame since 1978 and is named for the 1970 Hall of Fame enshrinee who first made a name for himself as a radio broadcaster in the 1930s before serving as baseball’s commissioner from 1951-65.

Michaels was one of eight candidates from the Frick’s National Voices category, part of the award’s three-year election cycle. The other finalists included Buddy Blattner, Joe Buck, Dave Campbell, Dizzy Dean, Don Drysdale, Ernesto Jerez and Dan Shulman.

“I’ve had a lot of wonderful moments in my career with a number of sports, obviously, but it all revolved around, early on, baseball,” Michaels said. “So in that sense, to think back on how it all began and what the cornerstone was, that made this award that much more special.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1944 and growing up a Dodgers fan, Michaels and his family moved to Los Angeles in 1959. After majoring in radio and television at Arizona State University, he began broadcasting the minor league baseball games of the Pacific Coast League’s Hawaii Islanders.

The big leagues beckoned and in 1971 the 26-year-old Michaels began a three-year stint broadcasting Cincinnati Reds games on radio and television. By 1974, he was broadcasting the San Francisco Giants, a position he held until signing with ABC Sports fulltime in 1977 as a backup play-by-play announcer for Monday Night Baseball.

“I had done a lot of baseball in the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s and some in the ‘90s. But it’s been so long,” Michaels said. “It’s the one thing that I really miss. So this kind of takes me back. I thought that this really completes the circle.”

Michaels, who has covered more major sporting events than any sportscaster in history, is the lone broadcaster to call the Super Bowl, World Series, NBA Finals and host the Stanley Cup Final for network television. Recognizable today after more than three decades as the voice of Monday Night Football and Sunday Night Football, among his most famous moments came during the Miracle on Ice at the 1980 Winter Olympics (“Do you believe in miracles?”) and the earthquake-interrupted Game 3 of the 1989 World Series.

His quarter-century broadcasting baseball includes, besides the Reds and Giants, work with NBC (1972), ABC (1976-89), and the Baseball Network (1994-95). Overall, Michaels has called eight World Series, six All-Star Games and eight LCS, as well as the 1995 Divisional Playoffs.

Despite his own impressive resume, Michaels still marveled at the impressive list of Frick Award winners that he has now joined.

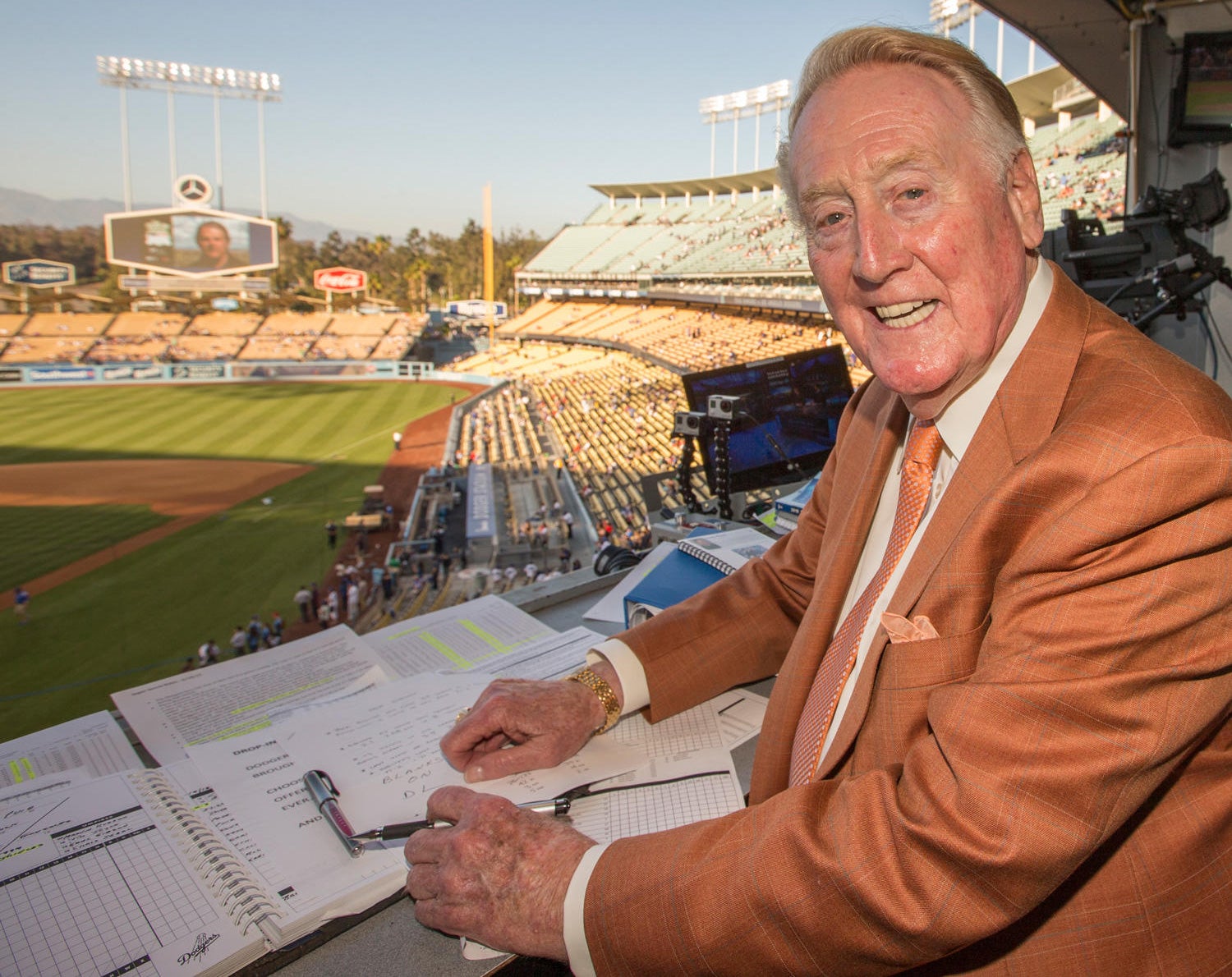

“I got to know a lot of those guys,” Michaels said. “Growing up listening to Vin Scully, who I know and we’ve become great friends. To this day we talk every month or so. Curt Gowdy – loved him. Just loved the way we went about it. Loved him as a man and as a friend. I knew Dick Enberg extremely well through the years.

“So I look at that list and I’m thinking, ‘Man oh man. That’s pretty good. That’s pretty exciting.’ In a way it kind of takes me back to my youth. And when I got into the business and became a major league broadcaster I got to know a lot of these men. It’s special.”

Michaels also shared a story about when 1981 Frick Award winner Ernie Harwell wrote him a special letter.

“When I was a kid in college and looking for a job and looking for advice, I wrote to a number of announcers, but I did not get a lot of responses. But the best and most meaningful and impactful to me came from Ernie Harwell,” Michaels said. “Ernie sent me a handwritten note. And so when I got to meet Ernie when I was doing big league baseball we did cross paths. I’ll never forget that.

“The premise of Ernie Harwell’s note,” Michaels remembered, “was work hard. It was something like, ‘You’ve got a lot of enthusiasm. I can see that in the letter you wrote to me. You really want to do this. Keep plowing ahead. Don’t lose your enthusiasm. Put in the grunt work and sooner or later that break is going to come for you.’ And he was right on all levels.”

Michaels’ only time in Cooperstown came when he accompanied the Giants when the team was to face the Red Sox in the annual Hall of Fame Game on Monday, Aug. 18, 1975.

“What I remember about that is we played a Sunday game at Shea Stadium against the Mets and we had a Tuesday game in Pittsburgh against the Pirates. So we flew up to Cooperstown after the Sunday game in New York,” he recalled.

Michaels then remembered a story from his visit to Cooperstown that involved a pair of pitchers on that Giants team.

“Those two pitchers and Art Eckman, who was my broadcast partner, we’re having dinner at whatever hotel we’re staying at in the dining room,” Michaels said. “And I started to talk about how there is nothing more exciting in baseball than a no-hitter. And I got them excited about it.

“Fast forward later that season one of those pitchers, Ed Halicki, pitched a no-hitter at Candlestick Park against the Mets on Aug. 24 (six days after Michaels’ dinner in Cooperstown). The other pitcher sitting at the table was John ‘The Count’ Montefusco, who pitched a no-hitter on Sept. 29, 1976 against the Braves. You talk about unbelievable occurrences. There you have it.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum