- Home

- Our Stories

- MLB Network’s Brian Kenny to speak at Museum’s Symposium

MLB Network’s Brian Kenny to speak at Museum’s Symposium

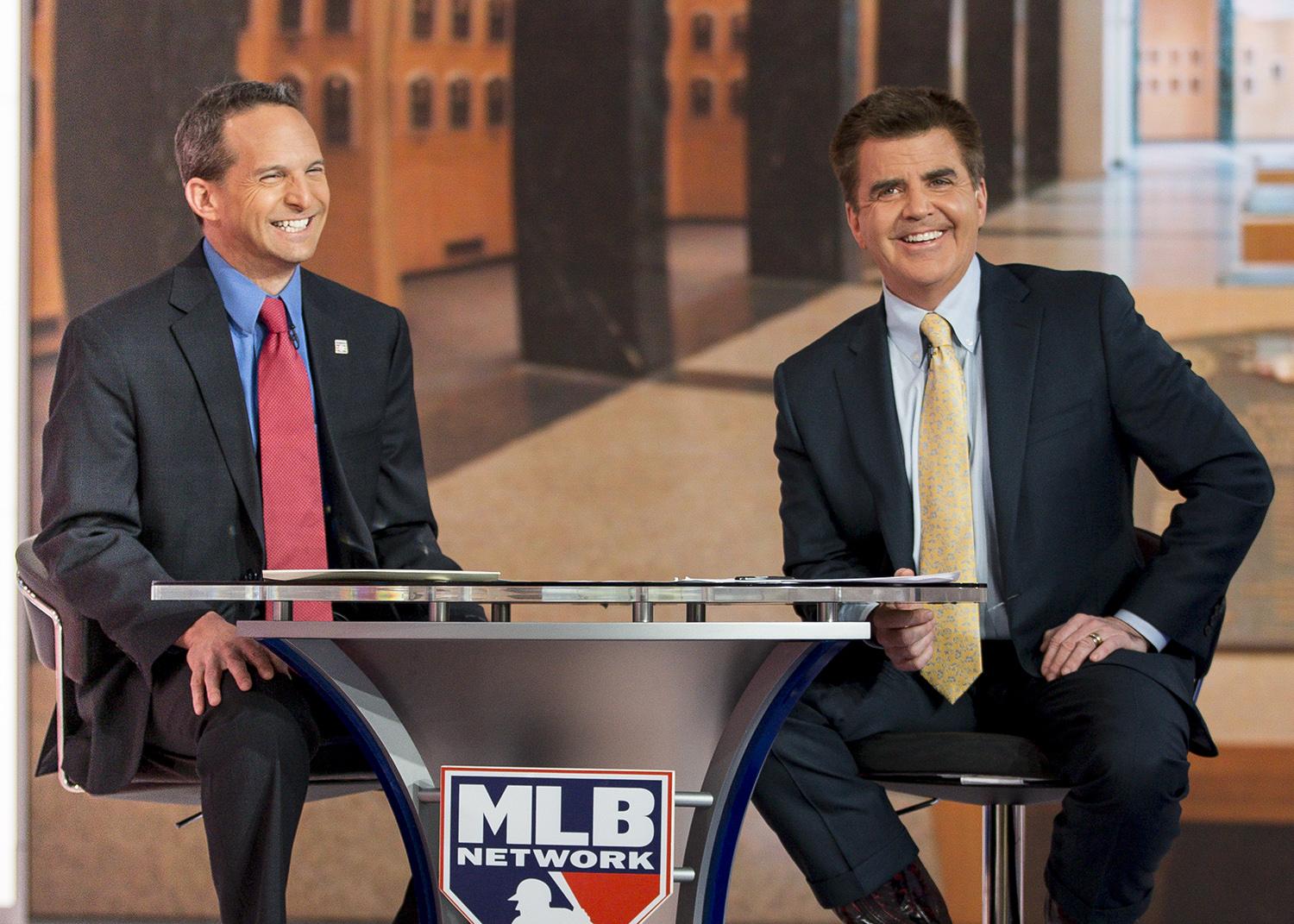

Broadcaster Brian Kenny, a familiar face and voice to baseball fans, will soon be in Cooperstown, a destination he has great affection for, and speaking about the sport he loves.

A fixture at ESPN for over a decade, Kenny joined MLB Network in 2011, where the passionate and opinionated host of MLB Now, among other shows, can be seen refuting a number of the long-held beliefs for those adhering to the game’s so-called “book.”

As part of the 29th Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, which will be held at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum from May 31 to June 2, Kenny is the keynote speaker, with his talk on the evening of Wednesday, May 31, entitled: “What Were We Thinking?: A History of Ignoring Competitive Advantage.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

According to Kenny, his Cooperstown presentation will be based on his most recent book, “Ahead of the Curve: Inside the Baseball Revolution Hardcover,” published by Simon & Schuster in 2016. The paperback is due out in July.

It was recently announced that Kenny, for his work with “Ahead of the Curve,” was one of three recipients of a 2017 SABR Baseball Research Award, which “honor outstanding research projects completed during the preceding calendar year that have significantly expanded our knowledge or understanding of baseball.”

During a recent telephone interview, Kenny, 53, spoke about a number of topics, including his upcoming talk, the state of the game, and his beloved Cooperstown.

HALL OF FAME:

Brian, what are your thoughts on giving the keynote address at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture?

BRIAN KENNY:

I’m still in the process of putting it together, but I think I’m going to go back over my book. There’s been some time elapsed since I wrote it, and since I gave my initial remarks on the book, to tell people what the book was about. So I’m going to go back through it and just piece together what I learned from my vantage point, which was looking at baseball history and looking at human resistance to knowledge. And go back over the examples of that and why I found it so fascinating, why I found the resistance to the sabermetric movement so interesting, and what I learned, which was this was nothing new in the history of baseball. And if it’s the history of baseball it’s the history of humans, not just baseball.

HOF:

Can you give some examples of this resistance to knowledge?

BK:

Relief pitching, defensive shifts, sabermetrics, and in the NBA, the three-point shot, and in the NFL, punting every fourth down. There’s lots of things that are just done due to tradition and convention, and continue to be done even though it flies in the face of logic. And what I found, why this is, is the combination of our own human brain and the underrated power of human herd mentality.

BK:

This is what makes baseball so fascinating because it’s an open competition for high stakes, for a lot of money, for your livelihood, for public adulation, so you would think you would use anything you could to beat your opponent. But the fact is you’ll only go against convention so much. You actually will be polite even when you’re going into battle against someone. There is real fear of straying from the herd. And especially in baseball. Really, it transcends baseball. It happens in all modes of business and life where you’ll only do things so different from the herd. You will constantly seek approval from your peers and your competitors. A manager of a Major League Baseball team now, if he did things very unconventionally, he’s immediately puts the spotlight on himself and there’s great resentment. If that guy succeeds he can continue to thrive and survive. The moment he fails, he will fail in spectacular fashion because the herd will have turned on him. And the repercussions are serious. So you learn fairly quickly that you do want to win if you are a major league manager, but you would also like to be employed the next time around. Because there will be a next time around. And if you ostracize yourself from the pack, you’re constantly trying to outsmart everyone, you will be thrust out of the herd.

Tony La Russa was called a genius and a mastermind but it was done in mocking fashion. It was done to make fun of him. He got attention but there was always snickering that he was trying to outsmart people. We value intelligence, we value someone who is thinking tactically, but in baseball I also find there is a cultural resentment for trying to be a smarty pants, for trying to outsmart people.

We’re in a new enlightened age now where someone like Joe Maddon is celebrated. So things have definitely changed in the analytics revolution. The people who are running the game have changed, the front offices have changed, but it’s only a few years back where it was vastly different.

HOF:

Your book has been out for almost a year now. Were you happy or surprised with the reaction?

BK:

I was thrilled. I really didn’t have any idea of what the reaction would be. I just wanted to write an interesting book. I wanted to get the things I believed in on the record. I wanted to get this out there. I realized I had an interesting vantage point to witness the revolution in thinking in baseball. I really didn’t think of how the audience will take it or how will it sell. I didn’t know any of those things. I just knew I wanted to get it out there and have a book I could be proud of. I’ve had so many people come up to me and say that they love it and it has changed the way they think. So there really is an audience out there that is still very new to this and it’s been very gratifying to get the reaction.

HOF:

I know you’ve been to Cooperstown many times over the years. Why does it have such a special place in your life?

BK:

Cooperstown definitely has a place in my heart. I’ve been going there since I was a small child. My father would take us there on family vacations. I really fell in love with baseball going to Yankee Stadium, going to Shea Stadium, and going to Cooperstown and learning about the history of the game. I loved reading about old baseball players and baseball teams when I was a little boy. And I always thought Cooperstown was magical. I always had a strong sense of the place. Through the years, my wife and I have gone up to Cooperstown, just the two of us, sometimes with the kids and sometimes without the kids, several times a year. We’ll go for my birthday in the fall and we’ll go on our anniversary in the winter. Our oldest daughter, Alexandra, was married there at The Otesaga Resort Hotel in September 2015. So clearly we love Cooperstown and the Hall of Fame. It has always been a strong part of my baseball foundation, that that was a place to go and visit and commune with baseball’s spirit and be there with family and just take it all in. Any trip I can make up to Cooperstown is one I always cherish.

HOF:

Do you have a sense of how many time you’ve been to Cooperstown over the years?

BK:

Three or four times a year for nearly 30 years. Well over 100.

HOF:

Regarding baseball today, are you happy with the current state of the game?

BK:

Absolutely. There’s a lot of different ways of looking at it. One, I am glad that the game has actually been very much in touch with the fans over the last few years. With the new commissioner, Rob Manfred, coming in and his open-mindedness to looking at the future of baseball and how it’s going and what needs to be looked at, I think that kind of sparked a whole renewed interest in how the game is being managed and what we do like and what we don’t like. So I think that attention is very healthy. I try and tell people things are changing rapidly: No collisions at home plate, no collisions at second base, replay being expanded. The game has changed quite a bit in only a few years. These are big changes. There were years and years and years of talk about change and how glacially it all moved. I think baseball was kind of famous for its slow movement toward progress or adjustments. And now things are happening quickly. And I think there’s definitely a sense that baseball is attuned to its audience and what it wants. I think now when you look at things like pace of play, I think it’s enormously important. I think the game does need to move faster. It doesn’t have to be a shorter game but it would be nice if it was a bit shorter.

HOF:

Can you talk about your own transition from ESPN, where you were involved with numerous sports, to becoming an important voice in baseball?

BK:

It has been marvelous. What I prefer is really just baseball. On a day-to-day basis, if I watch baseball all day long I’m happy. I really do love immersing myself and doing a deep dive every day into baseball. That really enabled me to write the book. As much as I love baseball, and I was doing Baseball Tonight at ESPN, once I started doing baseball all day, every single day, then writing the book just became a thing I could do because I was concentrating on baseball every day.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum