- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1959 Topps Ted Kluszewski

#CardCorner: 1959 Topps Ted Kluszewski

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

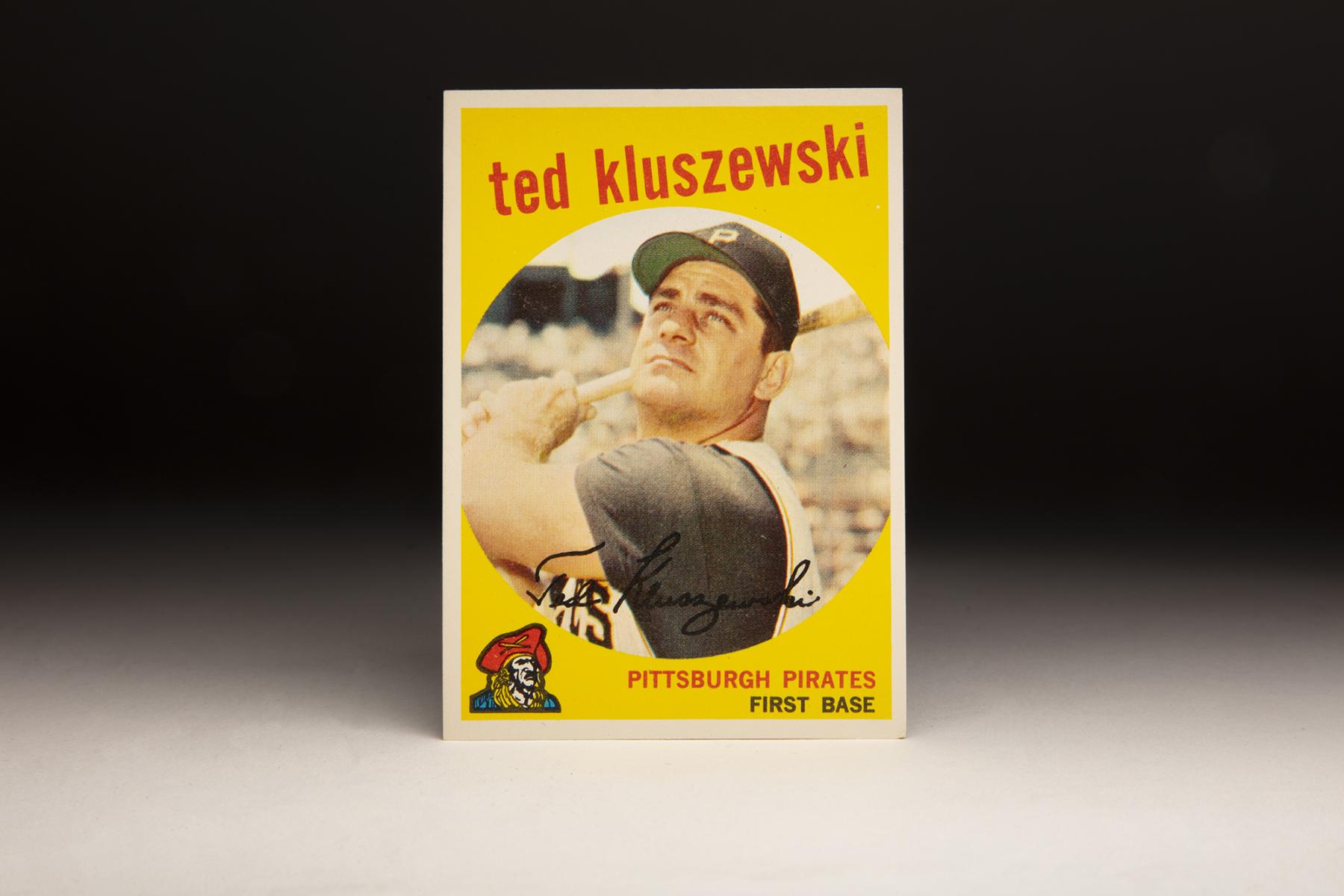

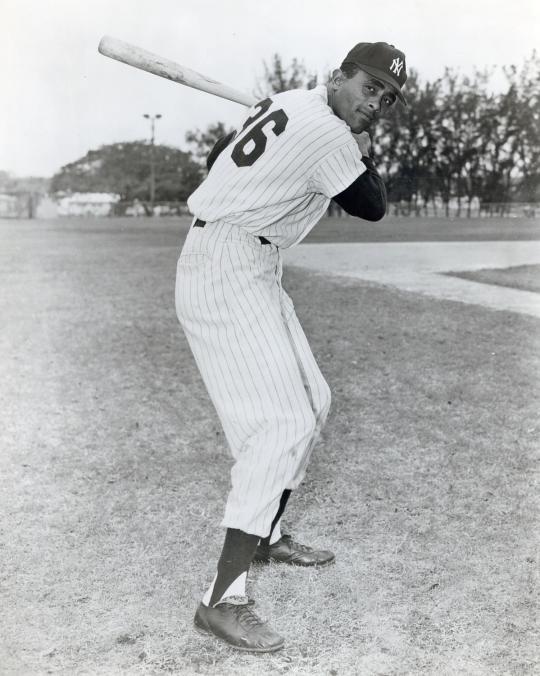

Ted Kluszewski’s 1959 Topps card gives us photographic proof that the mammoth slugger did not always cut out the sleeves of his uniforms to make room for his enormous biceps. When “Big Klu” played for the Pittsburgh Pirates in the late 1950s, the team used sleeveless vests, which would have seemed like a logical choice for the sleeveless look. But in posing for his Topps card, Kluszewski is clearly wearing the black Pirates undershirt below the outer vest, thereby covering up much of his upper arms.

Sleeves or no sleeves, Kluszewski takes on the look of a massive and majestic hitter. With those oversized biceps and that square jaw, Kluszewski epitomizes the stereotypical slugger of the 1950s – and then some. More than that, he seems to be taking special pride in his swing, even a practice swing occurring on the sidelines. With his chin up and eyes pointed well into the distance, Kluszewski seems to be imagining one of his best and most powerful swings, one that will produce a tape-measure home run.

Perhaps that’s how it is with good hitters. Even when they’re simply pretending to swing a bat for a Topps photographer, they still want everything to look just right.

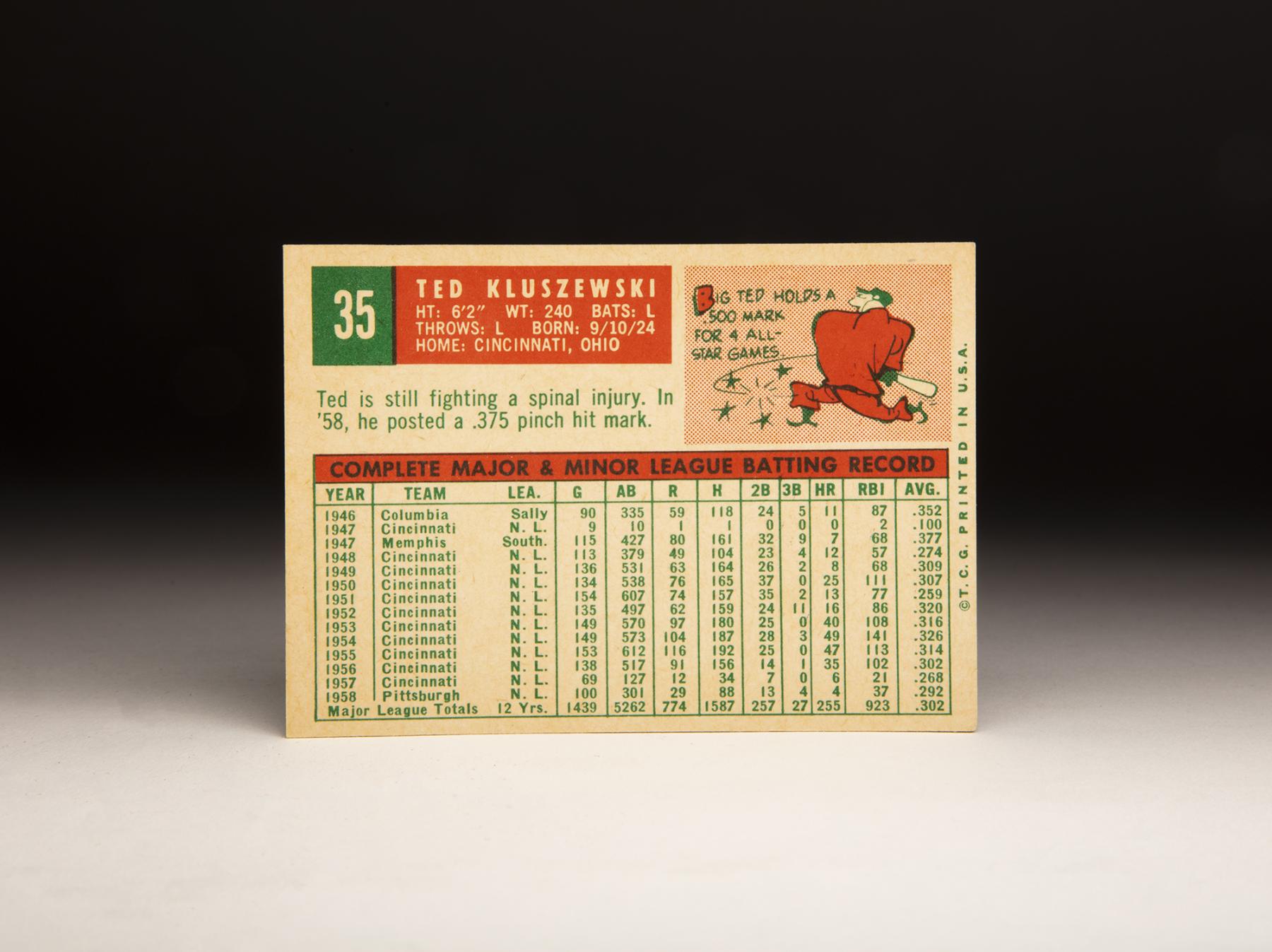

By the time that Kluszewski joined the Pirates, he still looked the part of a slugger, even if his on-field production indicated otherwise. He was now well into his thirties, on the downhill side of a very good career and fast approaching the end of his playing days because of chronic back trouble.

But during a five-year period from 1952 to 1956, Kluszewski was one of the game’s most prolific hitters. He was not just a frightening slugger who could hit 400-foot home runs, but a capable batsman who hit for high averages and rarely struck out. For a while, he was also a perennial All-Star who regularly finished in the top 15 when it came to National League MVP voting.

The son of Polish immigrants, a young Kluszewski first drew the attention of the Cincinnati Reds in large part because of happenstance. In 1945, the Reds spent Spring Training in Bloomington, Ind., because of World War II restrictions that banned teams from training in the South. One day, on the recommendation of assistant groundskeeper Lenny Schwab, the Reds invited Kluszewski to take part in batting practice. Kluszewski was a local star for Indiana University who had caught Schwab’s eye. According to some observers, Kluszewski put on such an impressive display in the batting cage, including an array of 400-foot homers, that the Reds soon offered him a minor league contract, including a bonus of $15,000.

Although the money was good for the time, Kluszewski did not sign with the Reds right away. Instead, he wanted to return to Indiana to play one more season of college football. He did just that, helping the Hoosiers to an undefeated season. The following year, Klu finally accepted the Reds’ offer.

The Reds assigned Kluszewski to Single-A Columbia for the 1946 season. He proceeded to tear up the pitching in the South Atlantic League, batting .352 in 90 games.

That performance convinced the Reds to bring him to Spring Training the following year. Kluszewski made the Opening Day roster, but received only three at-bats in four games before being reassigned to Double-A Memphis.

Kluszewski appeared even more capable of handling Double-A pitching than he had Single-A ball. He hit a league-leading .377 and slugged .543 in 110 games.

That level of domination mandated a return trip to the major leagues; in September, he came back up to Cincinnati but batted only 10 times, picking up his first major league hit in the process.

The Reds had bigger plans for Kluszewski in 1948. He eventually took over the first base job, replacing veteran Babe Young. Kluszewski did not become an overnight star, but did hit 12 home runs and batted a respectable .274 in 379 at-bats.

Playing in his rookie season, Kluszewski found the Reds’ jerseys uncomfortable and restricting. Given the size of his biceps, the jersey did not allow him the freedom of movement he wanted. “We had those flannel uniforms, and every time I’d swing, it would get hung up on the sleeve,” Kluszewski explained years later in an interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer. “I complained about it.”

The Reds offered no remedy, so Klu took a pair of scissors and sliced off the sleeves of the jersey, giving him an unusual bare-armed look. The Reds’ front office did not appreciate this fashion maneuver. “They got pretty upset,” said Klu, “but it was either that or change my swing. And I wasn’t going to change my swing.”

In time, the reasons behind the cutting of the sleeves changed. Even when the Reds arranged for a larger jersey, Kluszewski continued to cut the sleeves because he liked the look of unbridled power it gave him.

It’s safe to say that more than a few National League pitchers found the presence of Big Klu, with arms that looked like tree trunks, a bit intimidating. With his physique, one national magazine described Kluszewski as “Baseball Hercules.”

Still, the power that would eventually compliment those arms did not arrive in 1949.

Kluszewski hit only eight home runs for the season, while batting .309. Kluszewski believed that one of the culprits behind his lack of power was his “football shoulders.” According to Kluszewski, playing football in college had created a “muscular tightness” in his arms, which prevented his swing from being free and easy.

Remaining patient with their young slugger, the Reds saw the power come to fruition in 1950; Klu blasted 25 home runs while maintaining an average of .307. Remarkably, he struck out only 28 times. Defensively, he played a surprisingly nimble first base. Given his all-around play, he received some recognition from the National League writers, who placed him 18th in the MVP vote at season’s end.

Surprisingly, Kluszewski’s home run hitting fell off the next two seasons. He hit only 13 and 16 home runs, respectively, but did bat .320 during the latter season. The frustration ended in 1953, when Klu produced the offensive explosion that the Reds had long anticipated. Playing in 149 games, he batted .316 with 40 home runs and an OPS of .950. He struck out only 34 times, while walking 55.

Everyone took notice. Kluszewski made his first All-Star team, while also finishing seventh in the league MVP race.

Kluszewski’s breakout did not surprise the Reds. One of his earliest managers in Cincinnati, Luke Sewell, had compared him to an all-time great. “Ted reminds me a great deal of Lou Gehrig,” Sewell had told Tom Meany for Collier’s Magazine in 1951. “Not only because of his power, but because of his perseverance. Lou had to learn his trade one step at a time, too. It’s been even more difficult for Kluszewski, because he’s easygoing and really had to drive himself to work.”

Kluszewski’s laid-back manner also helped him become a popular man within the Reds’ clubhouse. While his massive frame made him an imposing figure upon first sight, the other Reds quickly came to know him as a genial and approachable teammate.

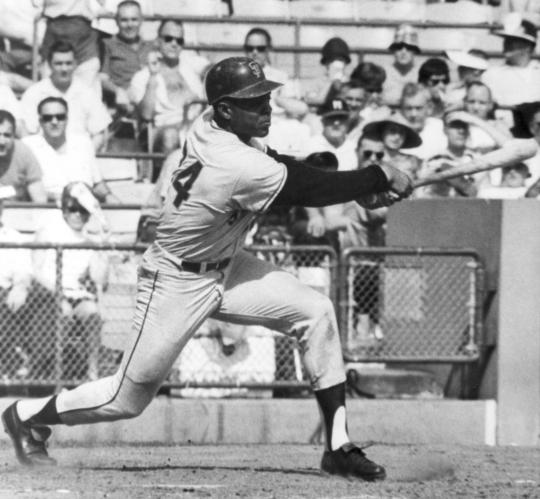

As well as Klu played in 1953, his peak had not yet arrived. The 1954 season would showcase Kluszewski in his full prime; he led the league with 49 home runs and 141 RBI, slugged a whopping .642, and batted .326. His walk total (78) more than doubled his strikeouts (35). Not only did he earn a spot on the All-Star team, but he also made a strong run at National League MVP, finishing second behind Willie Mays.

Kluszewski would never again match those numbers, but he remained an All-Star caliber player over the next two seasons. He hit over .300 each year and combined to hit 82 home runs over that span. He earned two more All-Star Game nods and two more finishes in the top 15 of MVP voting.

The latter season did, however, exact a large price. It was during the ’56 season that Kluszewski became involved in a clubhouse fight, which resulted in him hurting his back. The injury, involving a disc in his back, would render him a part-time player for the rest of his career.

Bothered by the back, Kluszewski appeared in only 69 games in 1957. Concerned about his health, along with his advancing age (he was now 32), the Reds decided to move on that winter. They traded Klu to the Pirates for another veteran first baseman, Dee Fondy.

After the trade to Pittsburgh, Kluszewski dropped about 15 pounds and regained enough health to appear in 100 games and hit .292. But the high batting average didn’t prevent him from losing the first base job to Dick Stuart. The reason? Klu’s power was gone. He hit only four home runs, the lowest output of any full season in his career. The back injury had rendered him a 225-pound singles hitter.

Returning to the Pirates for Spring Training in 1959, Kluszewski did not last the season in Pittsburgh.

After falling behind Stuart and Rocky Nelson on the Pirates’ depth chart, the Bucs traded him in August, sending him to the Chicago White Sox for outfielder Harry “Suitcase” Simpson and a minor leaguer. Over the balance of the season, Klu batted .297, but hit only two home runs in 101 at-bats.

While his White Sox numbers were modest, they were helpful to a singles-hitting team that was trying desperately to win the American League title. Kluszewski’s presence in the lineup offered protection to other Sox hitters, principally center fielder Jim Landis, helping the “Go Go Sox” clinch the pennant. And then Klu did major damage during the World Series against the vaunted pitching of the Los Angeles Dodgers. In six games, he batted .391, clubbed three home runs (nearly matching his regular season total of four), and slugged .826. The Sox lost the Series, but not because of Klu, who did his best to carry the offense.

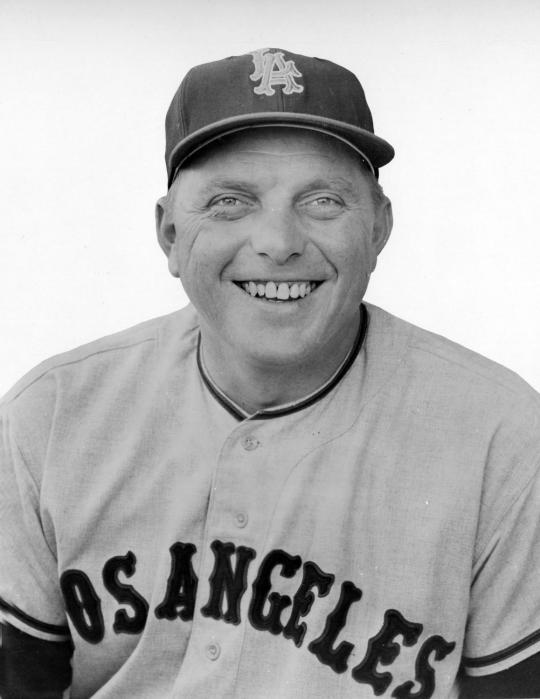

After another season of platooning in 1960, the White Sox left Kluszewski unprotected in the expansion draft. The Los Angeles Angels decided to draft the veteran first baseman, taking him with the 51st pick.

Used as part of a platoon with the hulking Steve Bilko, Kluszewski showed one last burst of power, hitting 15 home runs in 107 games.

Even with improved production, Kluszewski continued to muddle through back and leg problems. With his body breaking down, he decided to retire at season’s end. He would eventually return to the Reds’ organization as a batting instructor, a positon that he held for much of the 1970s, including the championship seasons of 1975 and ’76.

Observers of the “Big Red Machine” gave Kluszewski credit for the work that he did with players like Davey Concepcion and Cesar Geronimo, who were once considered ill-suited to hit in the major leagues but who both enjoyed long careers.

After his days as a major league hitting coach, Kluszewski took a job in the Reds’ minor league system. While working for the organization in 1986, Kluszewski suffered a heart attack, resulting in emergency bypass surgery. Shortly thereafter, he decided to retire from coaching.

In 1988, Kluszewski sustained a more devastating heart attack, one that took his life at the age of 63. For the rest of the season, the Reds wore black armbands in memory of their fallen slugger and coach.

Several of the Reds who had played for the likeable Kluszewski during his tenure as batting coach recalled him as a “Gentle Giant,” a man who rarely lost his temper and steadfastly believed in his young hitters. “Klu always had faith in me,” Concepcion told longtime Reds writer Hal McCoy, corresponding for the Sporting News. “He worked awfully hard with me, nearly every day. Lots of people said I’d never hit big league pitching and wanted to send me back to the minors.” Thankfully, Big Klu remained in Concepcion’s corner.

Perhaps Kluszewski remembered his own struggles during the early years of his major league career, and the patience that the Reds showed with him. That patience certainly paid off in the form of five incredible seasons in the 1950s, when Big Klu and his massive arms laid waste to the National League.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame