- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1959 Topps ‘Baseball Thrills’ Roy Sievers

#CardCorner: 1959 Topps ‘Baseball Thrills’ Roy Sievers

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

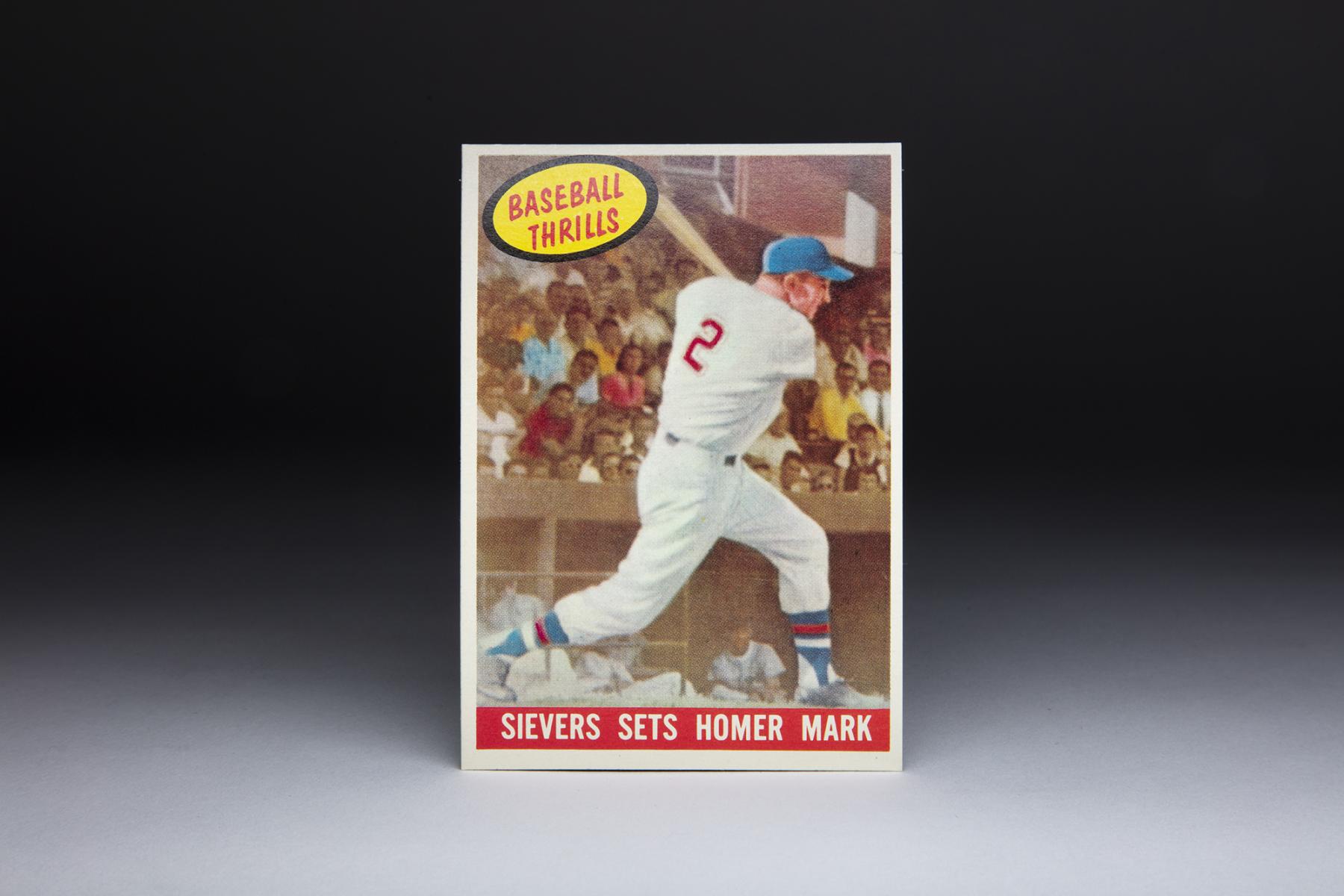

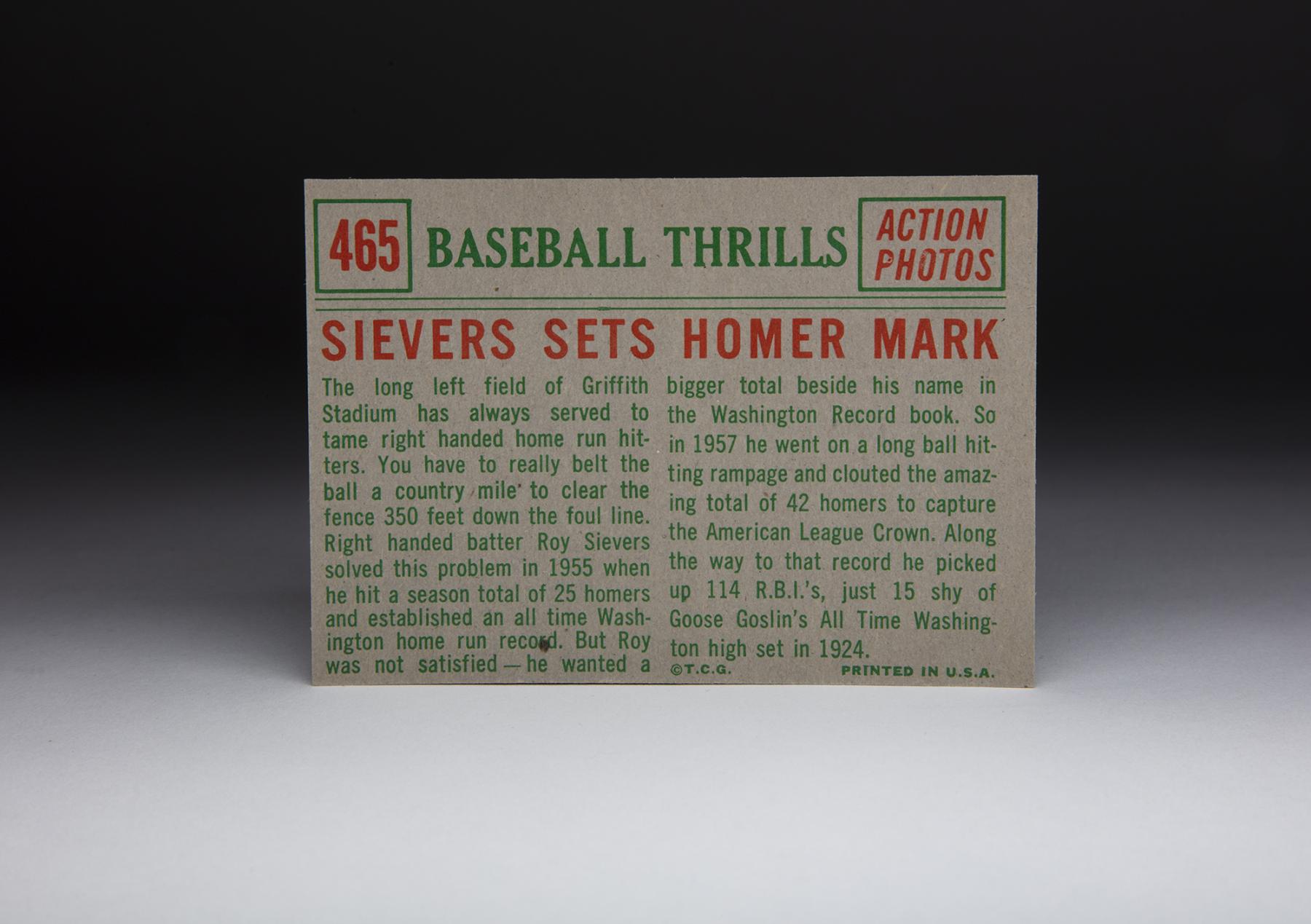

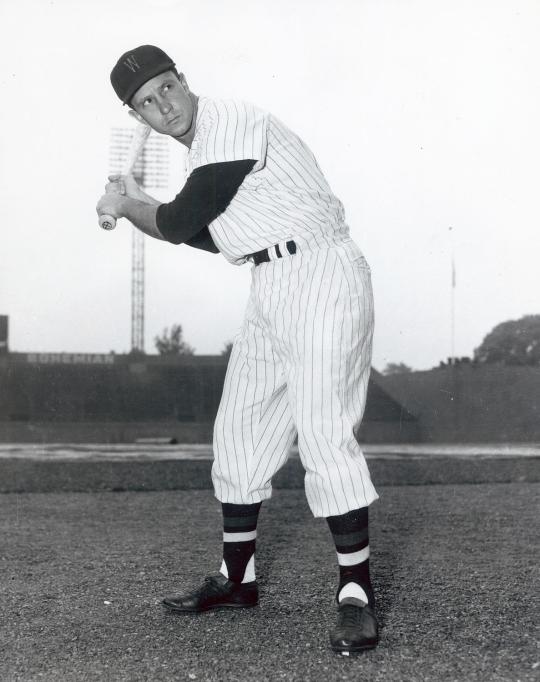

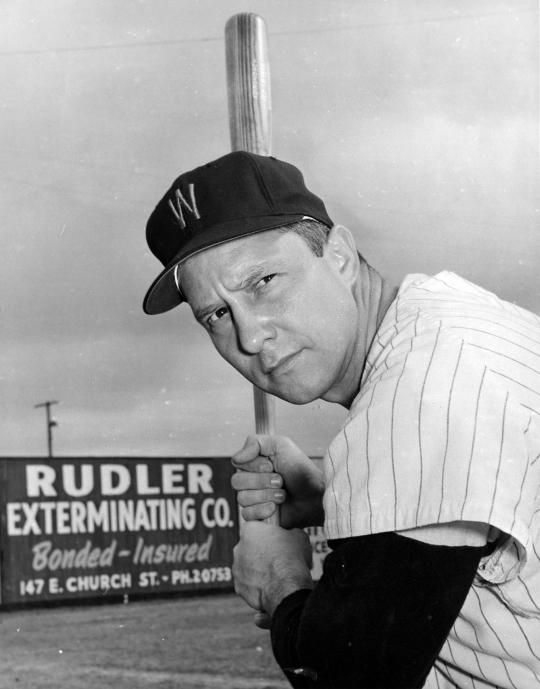

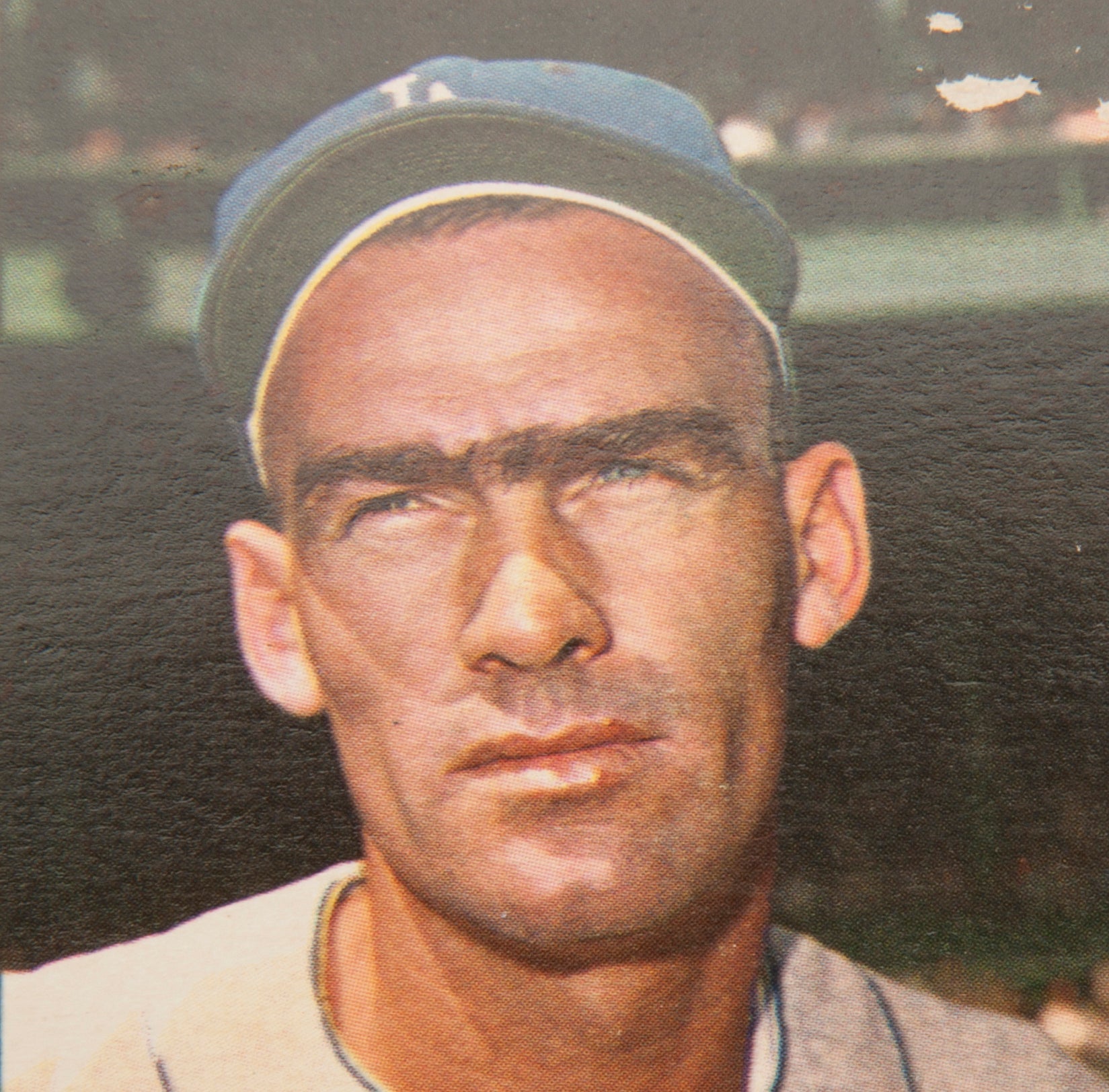

On more than one occasion, I’ve written that the Topps Company debuted action photography in its historic black-bordered 1971 set. So when you see this 1959 Topps shot of Roy Sievers, a card that is now 60 years old, you might ask, “What gives?” After all, Sievers clearly appears to be “in action” during this game at old Griffith Stadium.

Well, let’s clarify. When Topps included 52 action shots as part of its 1971 set, it was indeed the first time that the company featured full-color action photography. But for many years prior to’71, Topps had featured cards of players in action, only without the use of color film. What Topps did during the 1950s and ’60s was take black-and-white action shots, and then colorize them – with varying degrees of success. Some of the colorized shots were very good – so good that they closely resembled color photographs. Others were not done quite as well, making them look like drawings, or in some cases, take on a cartoonish hue.

Up until the early 1970s, it was very difficult to take color photographs of players in action, mostly because of the existing technology, specifically the low speed of the film being used. That begin to change in the 1970s, when high-speed color film allowed photographers like Doug McWilliams and others who freelanced for Topps to take quality shots of players as they moved on the playing field.

So why did Topps include Roy Sievers, with his bright blue cap, a red No. 2, and those gaudy red, white and blue stockings, in its subset of Baseball Thrills? The banner at the bottom of the card, declaring “Sievers Sets Homer Mark,” actually refers to two different statistical milestones from 1957. First, Sievers’ total of 42 home runs set a new single-season franchise record for his team, the Washington Senators. Second, Sievers’ home run total led the American League, making him the first Senator to do so. That was an especially impressive feat given the presence of other premier power hitters in the AL, principally Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams.

Sievers’ home run output becomes even more notable in light of the ballpark he played in: The double-decked Griffith Stadium, an old-time park that can be seen quite easily on the ’59 Topps card. The dimensions of the park did not favor a right-handed slugger like Sievers; the distance down the left field line measured no less than 350 feet. Yet, Sievers hit so many of his home runs into the left field bleachers that the media dubbed that area of the ballpark “Sieversville.”

By any measurement, Sievers’ season in 1957 was the best of his career. He also led the league in RBIs and total bases, batted .301, and posted an OPS of .967.

Despite playing for a last-place team, Sievers finished third in the American League MVP race, behind only Mantle and Williams.

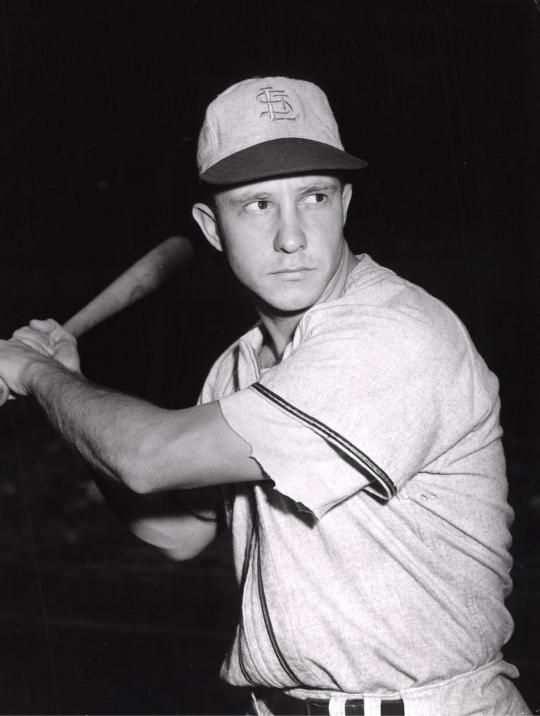

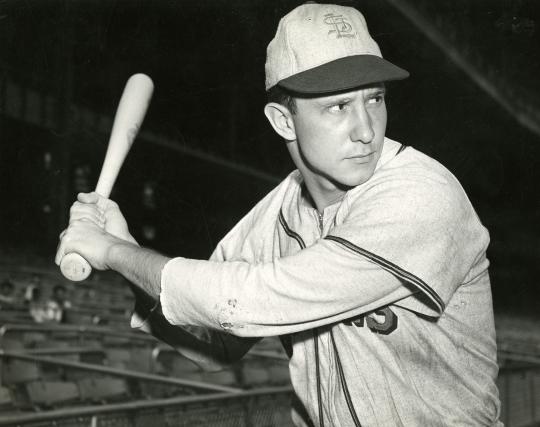

Sievers was by no means a one-hit-wonder. And his path to stardom with the Senators did not come easily. After signing with the St. Louis Browns in 1945, he missed all of the 1945 and 1946 seasons because of his military service as an Army MP (military policeman). Sievers finally returned to the states in 1947, with the Browns assigning him to the Hannibal Pilots of the Class C Central Association.

Sievers tore up the minor leagues in 1947 and ’48, forcing his way onto the big league roster on Opening Day of 1949.

Regarded as a can’t-miss prospect, Sievers quickly emerged as an outfield regular, splitting his time between center field and left field. Sievers more than justified the Browns’ belief in him as a high-grade prospect; he hit 16 home runs, batted .301, and compiled an OPS of .869. Those numbers earned him the Rookie of the Year Award, along with some back-of-the-ballot support in the league’s MVP race.

Sievers would never again match his rookie numbers during his time in St. Louis. In 1950, he endured the stereotypical “sophomore jinx,” starting the season in an extended slump and then losing his job in the Browns’ outfield. From there, injuries became the primary culprit. Over the next three seasons, he played in a total of only 134 games combined. When he did play, his hitting suffered. A dislocated arm, a nerve strain in his shoulder and lingering soreness in the area all played havoc with his career in St. Louis.

During the spring of 1952, a recurrence of a shoulder injury had Sievers wondering about his future in the game.

“This is the crossroads for me,” Sievers told sportswriter John Steadman. “Twice in two years, I have wrecked the same arm. Maybe I’m all through. Who knows for sure?”

After muddling through the 1952 and ’53 seasons, Sievers had even more reason for worry. Then came a major change in his career path. After the ’53 season, Browns owner Bill Veeck sold the team to an ownership group that moved the franchise to Baltimore. But Sievers never played a game as an Oriole. In February of 1954, the Orioles traded Sievers to the rival Senators for left-handed hitting outfielder Gil Coan. The deal would become a boon for both Sievers and the Senators.

Sievers regained both his health and his swing in Washington. In 1954, the Senators made him their regular left fielder and watched him hit 24 home runs and draw 80 walks, which made his .232 batting average less consequential. In 1955, Sievers raised his average to .271 while maintaining his power. He posted an OPS of .838 in 1956, before enjoying his career season of ’57.

In late September, the Senators honored him with “Roy Sievers Night.” Among those in attendance was Vice President Richard Nixon, a huge fan of the slugging outfielder. During the ceremony, Nixon came onto the field and shook hands with Sievers, leaving the All-Star outfielder with one of the highlight moments of his professional career.

In 1958, Sievers would put up another set of premier offensive numbers including a batting average of .295 and an OPS of .900. That capped off a remarkable half-decade for Sievers with the Senators.

In each of his first five seasons with Washington, Sievers played well enough to receive consideration for the American League MVP Award, even though his team never contended. His power numbers and overall offensive production were simply too good to overlook.

Sievers wasn’t just productive; he looked good playing the part of a prime time hitter. Sievers’ swing was so smooth and so picturesque that even Hollywood took notice. In the 1958 film, Damn Yankees, directors George Abbott and Stanley Donen used Sievers as the “swinging double” for lead actor Tab Hunter, who had little experience playing baseball. In scenes where Hunter’s character of Joe Hardy can be seen swinging the bat, it is actually Sievers standing in as his body double. Since the character of Hardy batted left-handed, the film of Sievers was reversed using mirror image technology. Sievers also signed a record-breaking contract with the Senators in ’58, spurring rumors that he might be traded as a way of cutting costs. Still, Sievers returned to Washington in the spring of 1959.

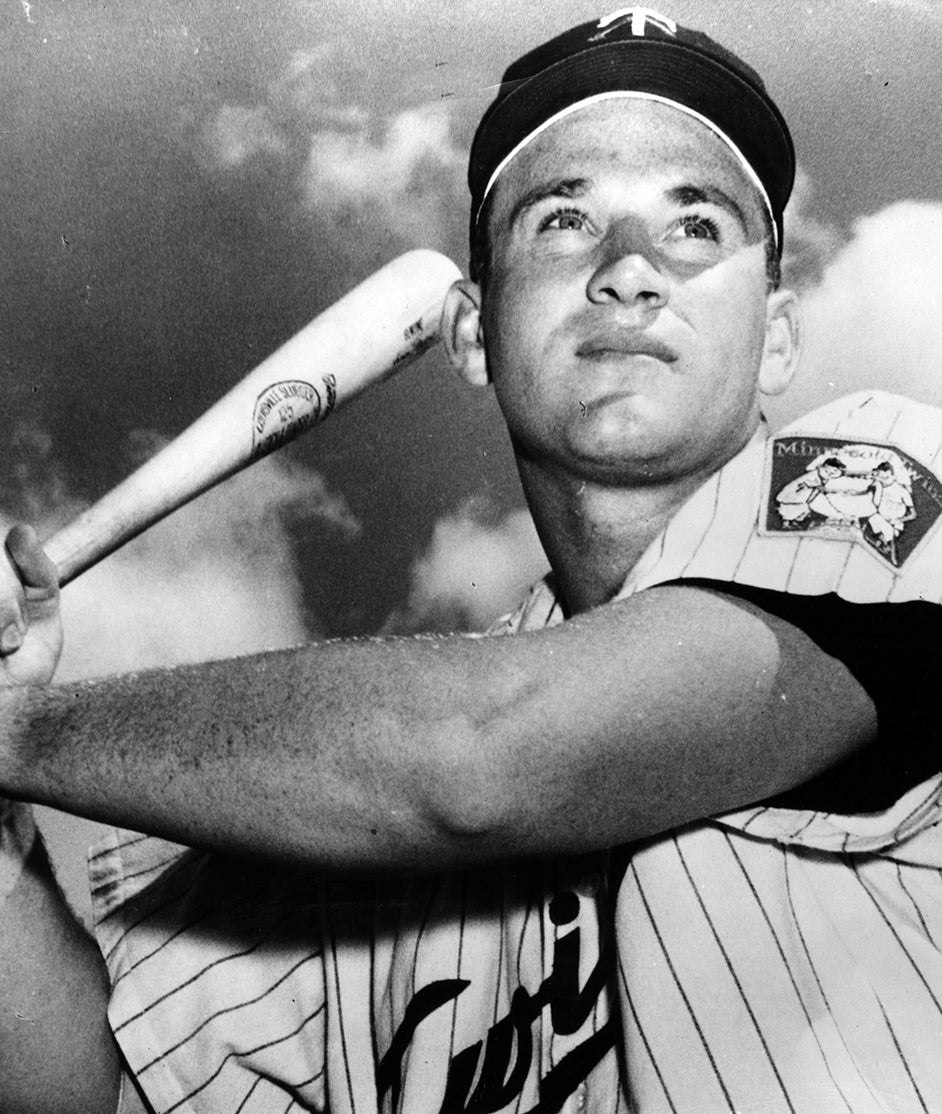

He hit 29 home runs that summer, but a series of nagging injuries cut down his playing time. With young sluggers Harmon Killebrew and Bob Allison on the way up, Senators general manager Calvin Griffith decided that the 33-year-old Sievers was expendable. That winter, he traded Sievers to the Chicago White Sox for a package of catcher Earl Battey, slugging first baseman Don Mincher and $150,000.

The Sox, now owned by former Browns owner Veeck and managed by Al Lopez, made Sievers a platoon first baseman, sharing time with fellow slugger Ted Kluszewski. Eventually, Sievers moved into the lineup on a fulltime basis. For the season, Sievers batted .295 with 28 home runs. Finally given the chance to play for a team with a winning record, something that had always eluded him in St. Louis and Washington, Sievers placed seventh in the league MVP voting. In July, the White Sox were leading the American League, leading some to speculate that Sievers would win the MVP. But the White Sox tailed off over the final two months of the season and finished third. Sievers’ manager took the blame. “I blame myself for not playing Roy Sievers every day,” Al Lopez told the Sporting News. “I didn’t realize that Sievers must play every day to keep his timing.”

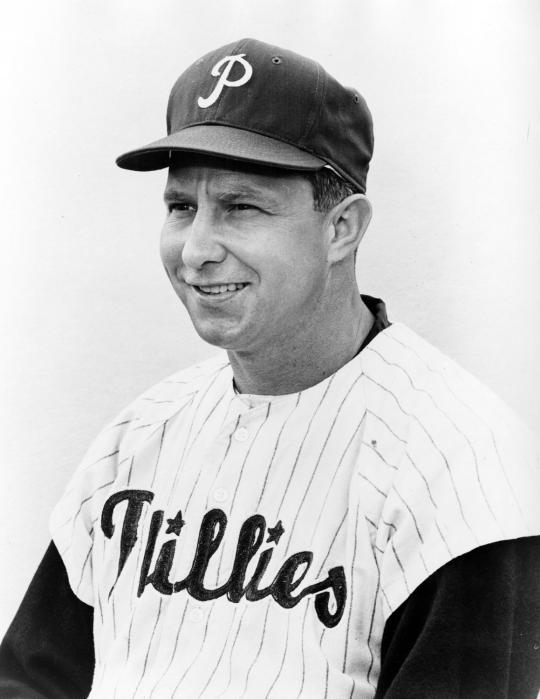

In 1961, Sievers put up nearly identical numbers for the White Sox and made his fifth All-Star Game. But the White Sox were an aging team, and one that was facing an imminent ownership change. When Veeck sold the team to the Allyn brothers, the Sox shipped Sievers to the Philadelphia Phillies for pitcher John Buzhardt and infielder Charley Smith.

Adjusting to a new set of pitchers and umpires in the National League, Sievers struggled at the start of the season. Through mid-June, he was batting only .190. But once Sievers became acclimated to his surroundings, his hitting improved. By season’s end, he had put solid numbers, including a .262 batting average and 21 home runs.

After another good season in 1963, Sievers came down with a calf injury at the start of the ’64 campaign and played only intermittently. Worried that he might be done, the Phillies sold him to the Senators.

Used mostly as a pinch-hitter, he played sparingly over the balance of the season, and then received his release in May of 1965. The 38-year-old tried to make comebacks with the White Sox and St. Louis Cardinals, but neither team would offer him a major league contract. With that, his 17-year career came to an end.

Sievers did not stay out of baseball for long. In 1966, he joined the coaching staff of the Cincinnati Reds. He then managed in the New York Mets’ system for two seasons before moving on to the Oakland A’s organization. Ultimately, Sievers felt that his salaries as a minor league manager would not allow him to support his family, so he left baseball and took a job with a freight company in St. Louis. He worked at the company for 18 years before retiring. Over the years, Sievers maintained a connection to baseball by attending reunions of the St. Louis Browns. A member of the Browns Historical Society, he enjoyed retirement in St. Louis until 2017, when he passed away at the age of 90. Like many standouts from the 1950s, Sievers has become somewhat forgotten by time. Perhaps that’s because he starred for two now-defunct franchises. Another factor may have been the bad fortune of never playing for a team good enough to reach the World Series. He was also a quiet and modest man, one who didn’t do much in the way of bragging. But at one time, Roy Sievers thrilled the fans of Washington to no end, as we’re so well reminded 60 years later by his surreal, colorized action shot on a vintage Topps card.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame