- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Bob Jones

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Bob Jones

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

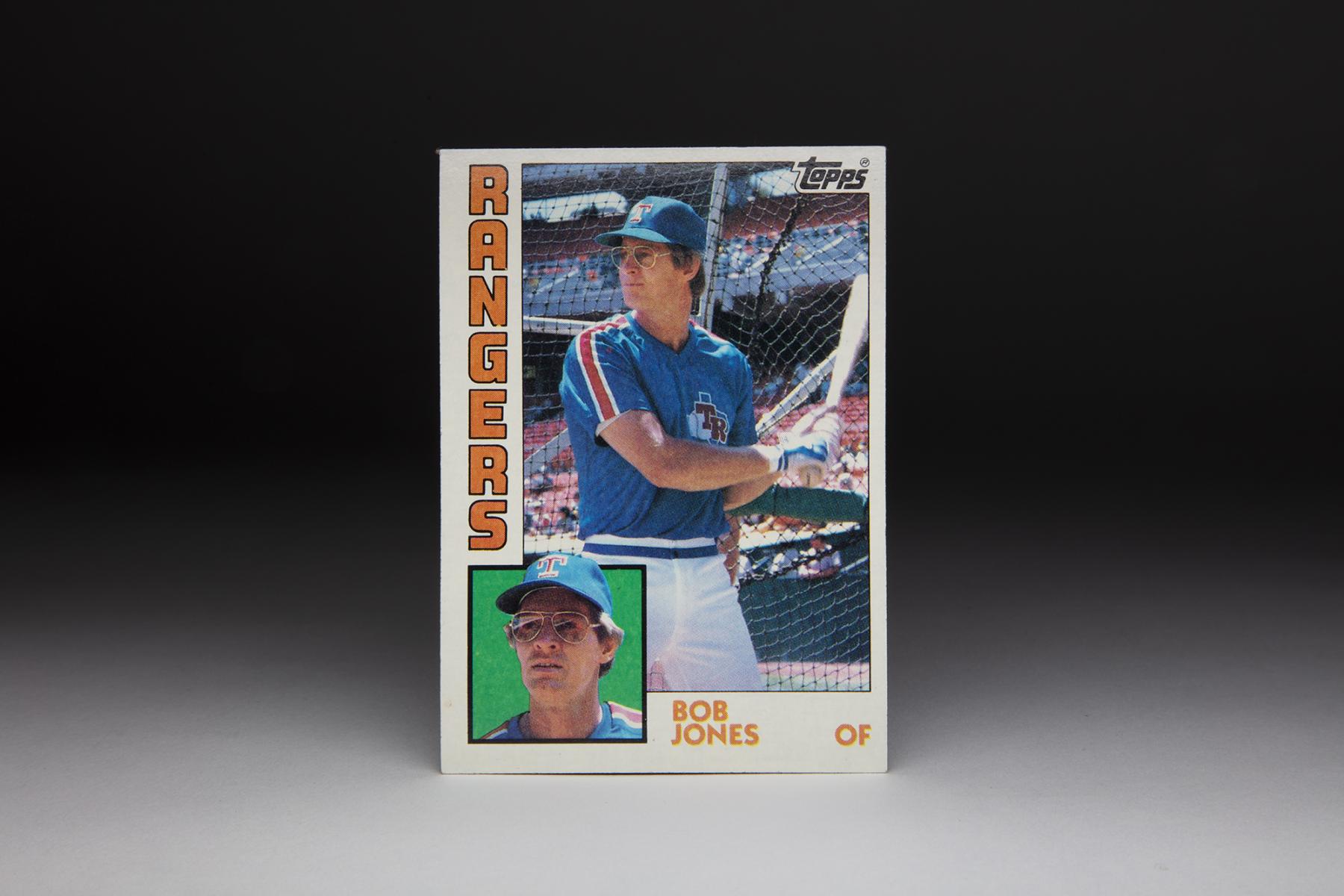

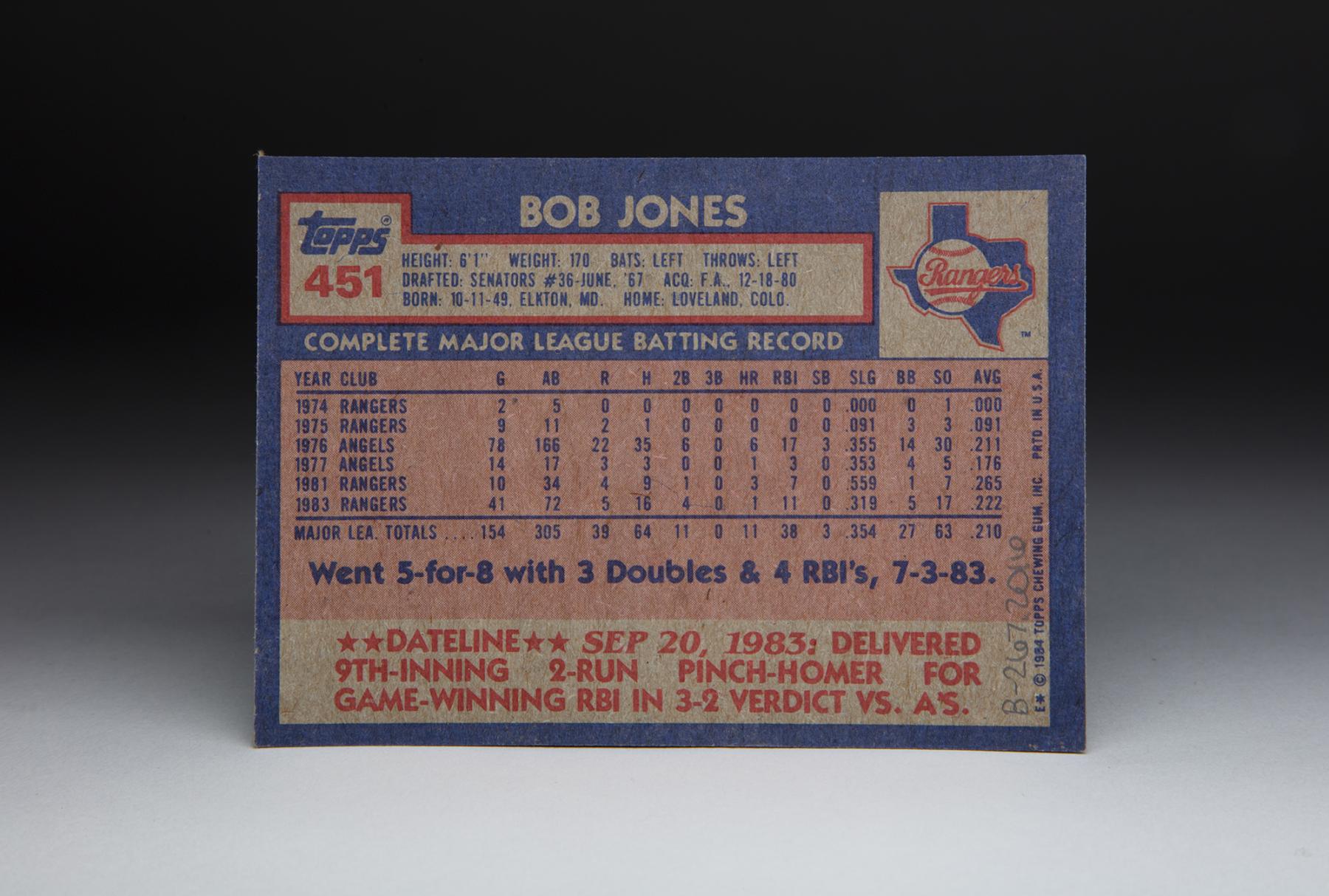

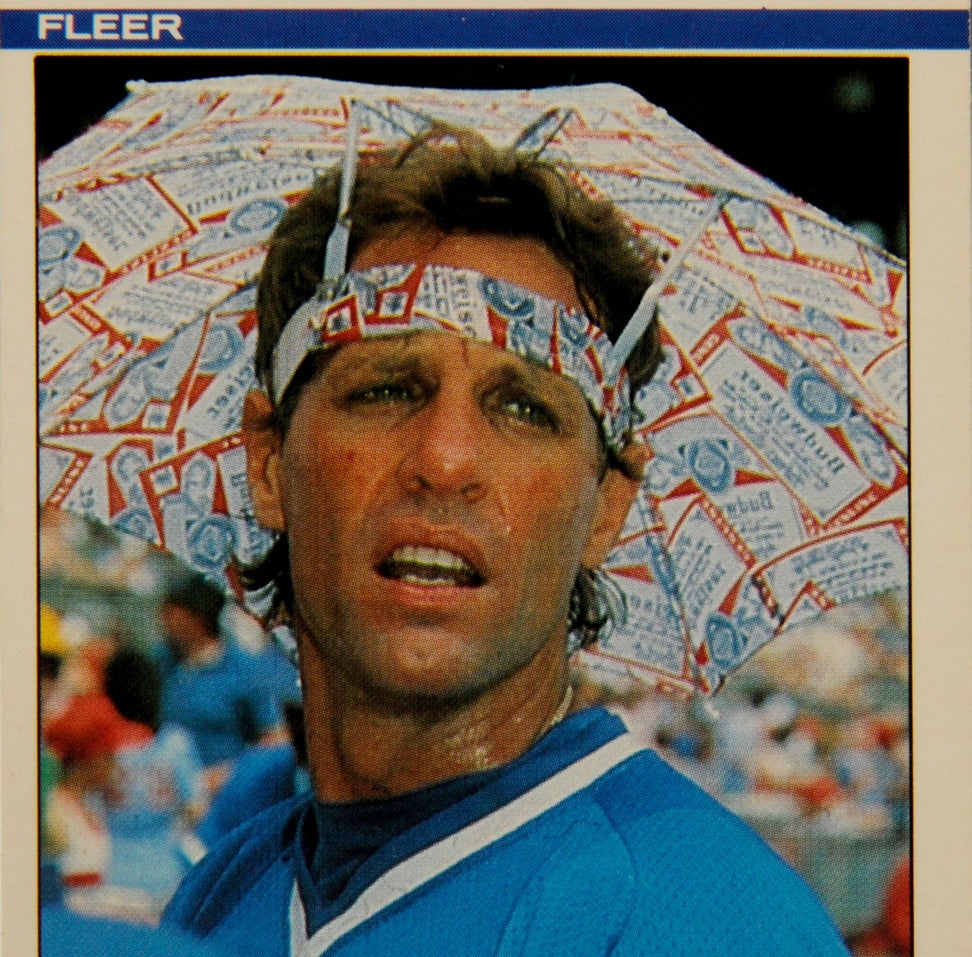

In looking at the 1984 Topps card of Bob Jones, there is nothing inherently unusual or unique about it.

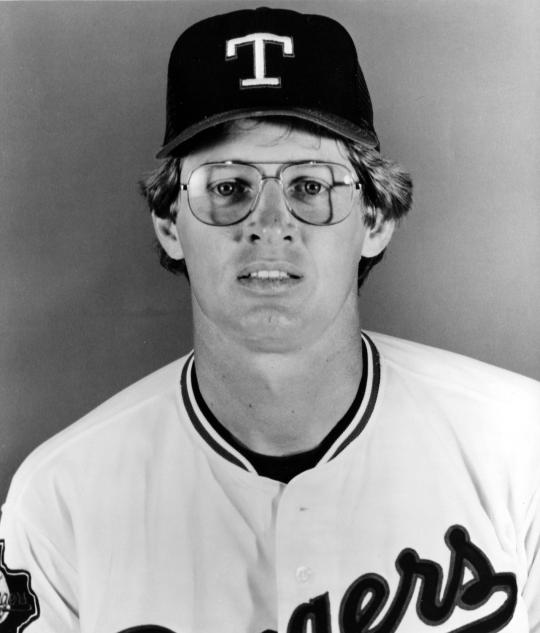

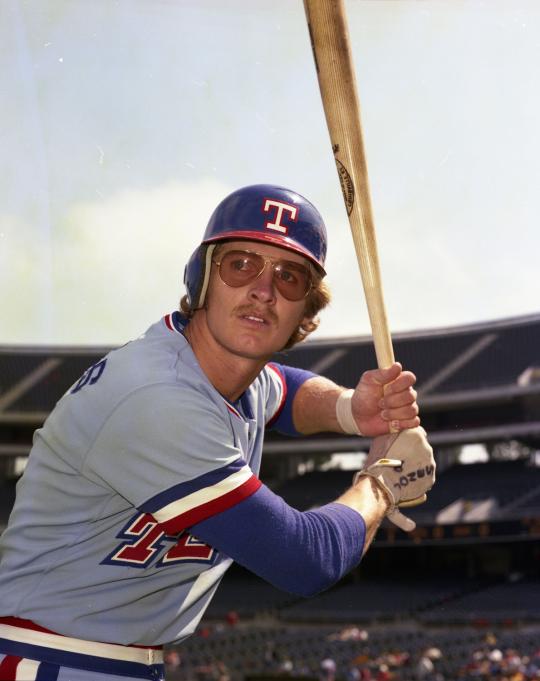

In both the larger and smaller photographs, Jones looks like a fairly typical player from the era, sporting those oversized tinted glasses (which had really first come into vogue in the 1970s). He is wearing a blue Texas Rangers’ warmup jersey, which the team typically used for batting practice. In several ways, this is a standard issue photograph for a player of early 1980s vintage.

What the card does not show us is, or give any hint at it, is the physical trauma that Bobby Jones has endured. By the time that this photo was taken, sometime during the 1983 regular season, Jones had suffered severe hearing loss. The damage to his hearing came as the direct result of his participation in the Vietnam War, more than a decade earlier. The effects of serving in that war not only damaged Jones’ physical well-being, but left him with emotional scars.

Back in the 1960s, Jones emerged as a standout outfielder at Elkton High School in Maryland. Scouts regarded him as a pro prospect, but hardly of the blue-chip, can’t-miss variety. It wasn’t until the 36th round that the Washington Senators selected Jones.

The Senators assigned the left-handed hitting outfielder to Geneva of the NY-Penn League. As a rookie, he batted an unimpressive .217 with no home runs in 19 games. In 1968, he didn’t fare much better as a sophomore, batting .246 with five home runs in just over 100 games in the Western Carolinas League.

In 1969, Jones started another season in the Western Carolinas, batting a respectable .270 in 20 games, albeit with little power. The Senators bumped him up to a slightly higher classification, the Carolina League, but a .198 batting mark in 39 games indicated that he had made little progress.

To put it bluntly, the teenaged Jones played so poorly in the lower reaches of the Senators’ system that he seemed incapable of sustaining a professional career, let alone having any kind of chance of making the major leagues. Jones’ attitude did not help matters; he didn’t seem to take the game seriously. At times, he simply went through the motions of being a professional ballplayer.

The Senators could have been excused for giving him his unconditional release after only three seasons.

A career-changing moment came in December of 1969. No, the Senators did not give Jones his walking papers. Instead, the U.S. Military summoned Jones. The Army informed Jones that he was being called into service, beginning what would be a 14-month stint in Vietnam. His life would soon change drastically.

The Army told Jones to report to its Americal Division, where he would be assigned to an infantry brigade artillery unit. While serving the Americal Division, Jones was stationed at a remote base called LZ Siberia. During the spring of 1970, the firebase came under attack. The enemy shelled the base for 45 consecutive days. The constant barrage resulted in the deaths of numerous soldiers within the division.

Somehow Jones survived the attacks, but not without a heavy price. As a result of the thunderous noise created by the repeated shelling, Jones suffered significant hearing loss in both of his ears and had to be fitted with hearing aids in each ear.

For his bravery throughout the month-and-a-half-long barrage, Jones earned the Bronze Star. But neither the awarding of a medal, nor his hearing loss, resulted in an immediate discharge. He would remain in Vietnam for nearly another year, until February of 1971.

Without question, the Vietnam War had taken a heavy toll on Jones. But it also changed his attitude and his outlook. Years later, Jones conducted an interview with Oklahoma newspaper writer Bob Hersom, who asked him about his time in Vietnam.

“Was it worth it?” Hersom asked Jones during the 1993 interview. Jones’ answer stunned the writer. “Career-wise, I’d say yes. I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for Vietnam. I was just going through the motions as a player.”

More intent to make the most of his career in professional baseball, Jones reported to the Senators’ new minor league affiliate in the Western Carolinas League, located in Anderson, S.C. Far more determined than his first go-round, Jones batted .321 with 20 home runs during the 1971 season. His .944 OPS led the team.

In 1972, the Senators relocated their franchise to Arlington, Texas, where they became known as the Rangers.

In the meantime, Jones continued his sudden climb. The Rangers had him bypass Double-A ball completely, instead assigning him to their Triple-A affiliate at Denver. Jones didn’t hit with as much power at Denver as he did at Anderson, but a .287 batting average and a .340 on-base percentage proved that he could hold his own against significantly advanced competition.

In 1973, the Rangers moved their Triple-A affiliate to Spokane of the Pacific Coast League. After a decent season in 1973, Jones exploded in ’74, lifting his batting average to an even .300, hitting 16 home runs, and stealing a career-high 15 bases. Just before the end of their regular season, the Rangers called Jones up, allowing him to make his major league debut on Oct. 1. Jones would appear in one more game before the Rangers’ season came to an end, going hitless in five at-bats. Still, it was remarkable that he made the big leagues at all, after the struggles of his first three minor league seasons.

In 1975, the 25-year-old Jones reported to Spring Training, hoping to make the Rangers as a backup outfielder. A so-so spring resulted in another demotion to Triple-A. Jones spent the first half of the summer at Spokane, racking up solid numbers, before being recalled in mid-July.

Jones remained with the Rangers for the rest of the season, but appeared in only nine games. He did manage to pick up his first major league hit, but it was his only one in 11 at-bats. It was a frustrating season for Jones, who wondered what he needed to do to earn a more permanent role in Texas.

A break came his way the following May, when the Rangers tried to slip him through waivers, only to have the California Angels place a claim. Jones happily reported to California, a team that needed some help in the outfield, particularly in center field. After joining the Angels, the Sporting News ran a story about Jones, his background, and his time in Vietnam. In the article, Jones talked about his military role in Vietnam as a “section chief,” overseeing the operations and maintenance of a 105 mm. howitzer. “I’d carry the shells [for the howitzer] and they were 50 pounds each,” Jones told Angels beat writer Dick Miller. “And I’d swing the 12-pound sledgehammer that we used to drive in the stakes that held the gun down.”

While that was physically laborious work, it paled in comparison to what Jones had experienced at LZ Siberia. Curiously, the article made no mention of the 45-day barrage he had sustained at that remote base, along with the loss in his hearing. It seemed that Jones wasn’t quite ready to relive those horrors.

The Angels gave Jones a chance to play as part of a revolving door arrangement in center field and as a part-time DH. He appeared in 78 games, hitting six home runs. But he batted only .211 and compiled a suboptimal OPS of .629. Despite his poor hitting, the Angels kept Jones on their Opening Day roster in 1977. In April and May, he came to bat 17 times, picking up only three hits. So it was back to the Pacific Coast League in 1977, this time to Salt Lake City. Jones overmatched the league’s pitchers, putting up a batting average of .340, 18 home runs and an OPS of 1.043.

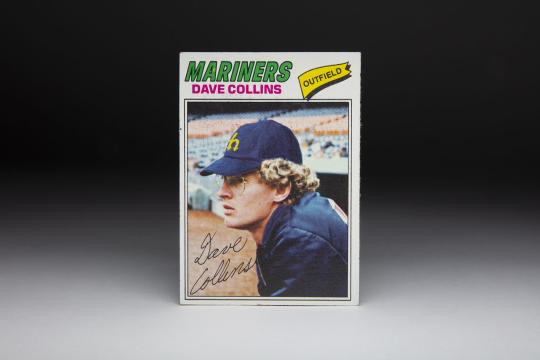

The 1977 season also saw Jones become involved in a baseball card oddity. That spring, Topps issued player cards for players on the Seattle Mariners, one of the major leagues’ two new expansion teams. The Mariners’ cards included an airbrushed shot of Dave Collins, a former Angels outfielder who had played with Jones in 1976. But in producing the card of Collins, someone at Topps inadvertently substituted a photograph of Jones, who can be seen wearing a classic 1970s era perm. With his perm, Jones looks nothing like Collins, but that didn’t prevent a case of mistaken identity. As a result, Jones appeared on two cards in the 1977 Topps set: Collins’ card and his own.

In 1978, Jones returned to Salt Lake and continued to dominate. It was obvious that he was too good for the Pacific Coast League, but perhaps not quite good enough to hold onto a steady job with the Angels. The following January, the Angels released Jones from his contract, allowing him to sign a more lucrative deal with the Chunichi Dragons of the Japanese Leagues.

After a two-year stint in Japan, Jones returned to the Rangers’ organization in 1981. He started the season at Triple-A Wichita before earning a promotion to Texas in September. In 10 games, Jones hit three home runs and posted an OPS of .845, the best stretch of his major league career.

Jones resumed the Triple-A shuttle over the next two seasons, before establishing himself as a fulltime major leaguer in 1984 and ’85.

Like many of his fellow veterans, Jones continued to feel the effects of the war years long after his Vietnam service had ended.

It was during the 1985 season, one year after this Topps card came out, that Jones was on a road trip for the Rangers, when he began to experience nightmares. The nightmares included vivid flashbacks to his days in Vietnam.

The flashbacks became so bad that Jones could hardly sleep over a stretch of three nights. The next day, he sat down to eat with team trainer Bill Zeigler in the Rangers’ clubhouse. Jones began visibly shaking. He tried to control the shaking, but could not. Zeigler asked him what was wrong. A few moments later, Jones broke down and began to tell Zeigler of the horrifying memories he had of his time serving in Vietnam.

By telling Zeigler about what had happened, Jones made some progress in dealing with his emotional state – and the remnants of his time in battle. Somehow he continued his playing career for the rest of 1985 and the next two seasons, before retiring. On the surface, his career batting average of .221 seems unimpressive, but given the difficult start to his minor league days, coupled with the first-hand anguish of Vietnam, it’s remarkable that Jones carved out a career of nine seasons in the major leagues.

Even through his experience with the brutality of war, Johnson considered himself fortunate. “I'd say I'm lucky,” said in his 1993 interview with Hersom. “We were out on a firebase, out in the middle of nowhere, getting hit by rockets and mortars and rifles all the time, and I came back without a scratch. We had a lot of guys get killed and wounded, but I was one of the lucky ones.”

After retiring as a ballplayer in 1987, Jones would achieve success as a minor league manager. He would embark on three different stints as the manager of the Triple-A Oklahoma City franchise, which was first known as the 89ers before becoming the Red Hawks.

Extremely popular with his players, Jones became the most successful manager in Oklahoma City’s century-plus of professional baseball. In August of 2010, with the Rangers on the verge of moving their Triple-A team out of Oklahoma City, the RedHawks honored him with “Bobby Jones Day” at the ballpark. In his typically humble manner, Jones expressed his thanks in an interview with The Oklahoman. “It’s pretty cool, isn’t it? They didn’t have to do all this. It’s really nice.”

After a brief stint as a Rangers coach, Jones moved into the Rangers’ front office as a special assistant for player development, a position that he continues to hold. Remarkably, it’s been nearly 50 years since he endured the nightmare of Vietnam. Yet, Bobby Jones has done more than just survive the anguish of war; he has found a way to make a good life out of baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame