- Home

- Our Stories

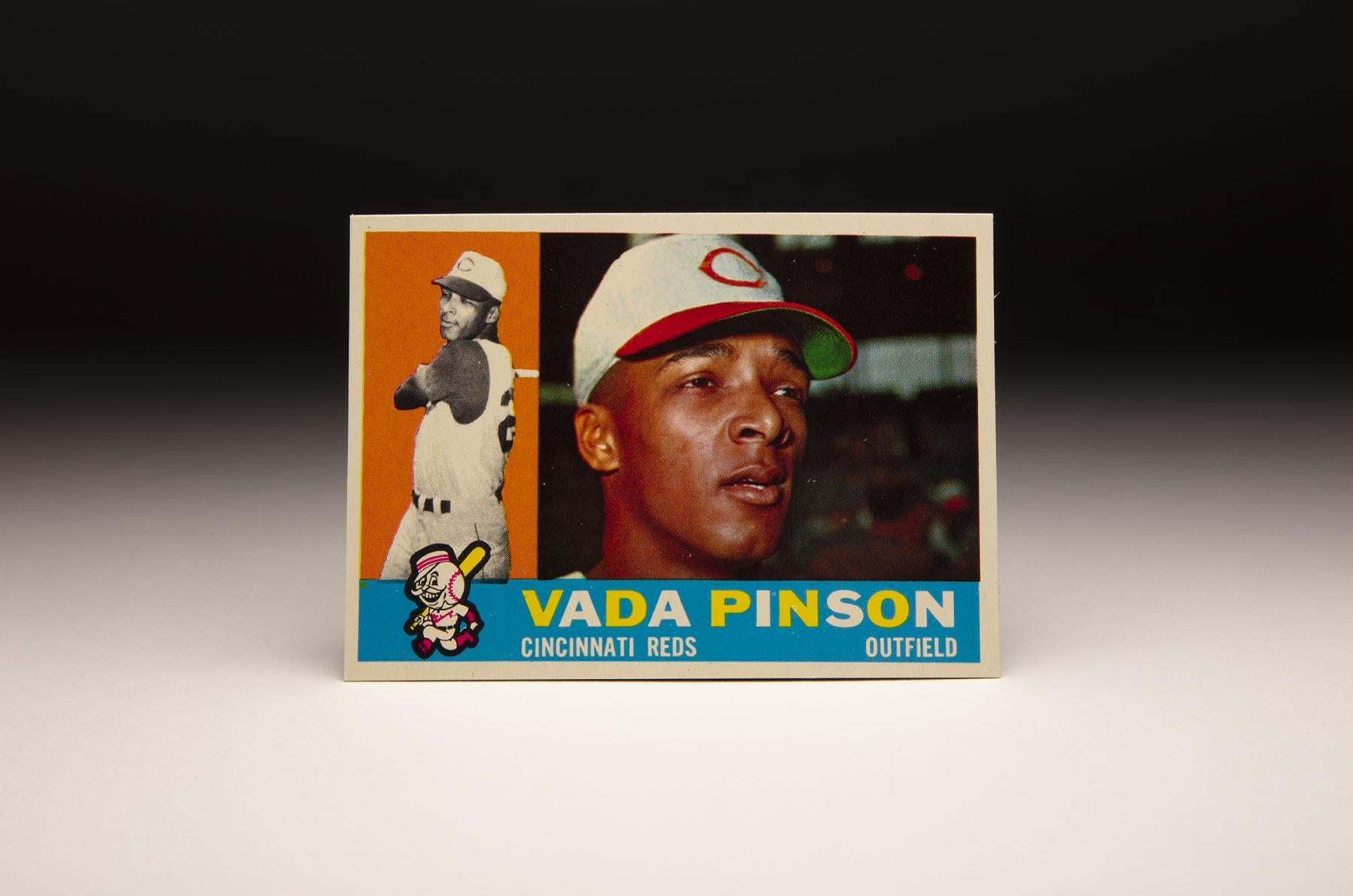

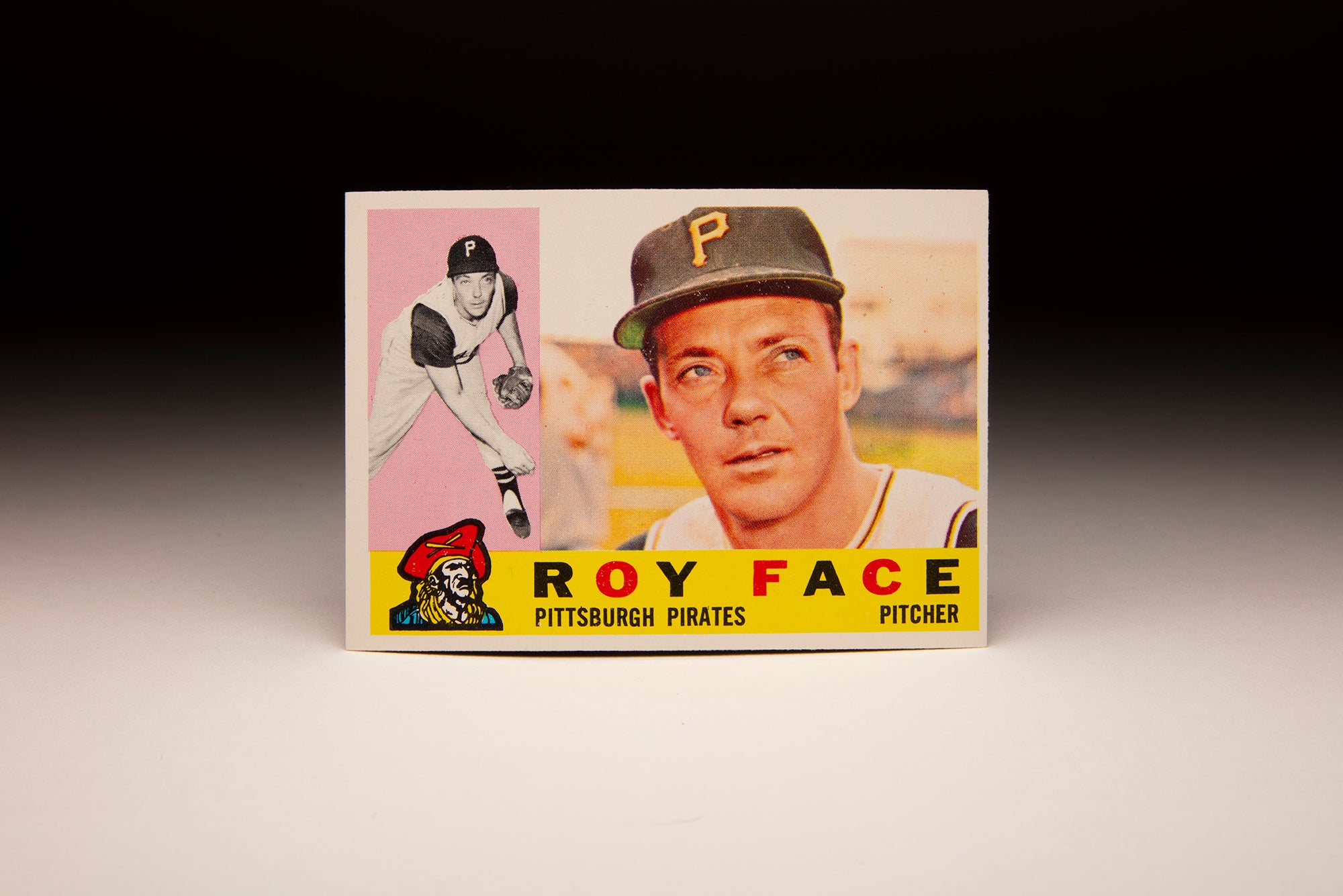

- #CardCorner: 1960 Topps Vada Pinson

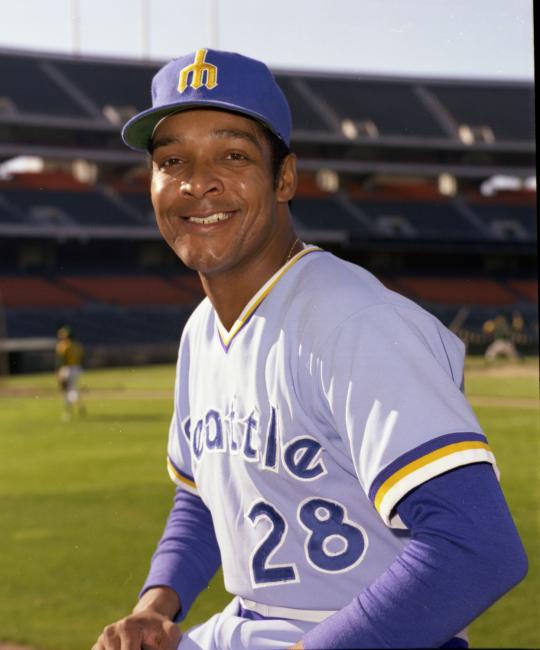

#CardCorner: 1960 Topps Vada Pinson

In his first full seven years as a big leaguer, Cincinnati Reds center fielder Vada Pinson recorded five seasons with at least 300 total bases.

Here’s the list of center fielders who matched or exceeded that production in that timeframe: Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio and Mike Trout.

Playing in an era with some of the top outfielders ever to take the field, Pinson was considered one of the game’s best.

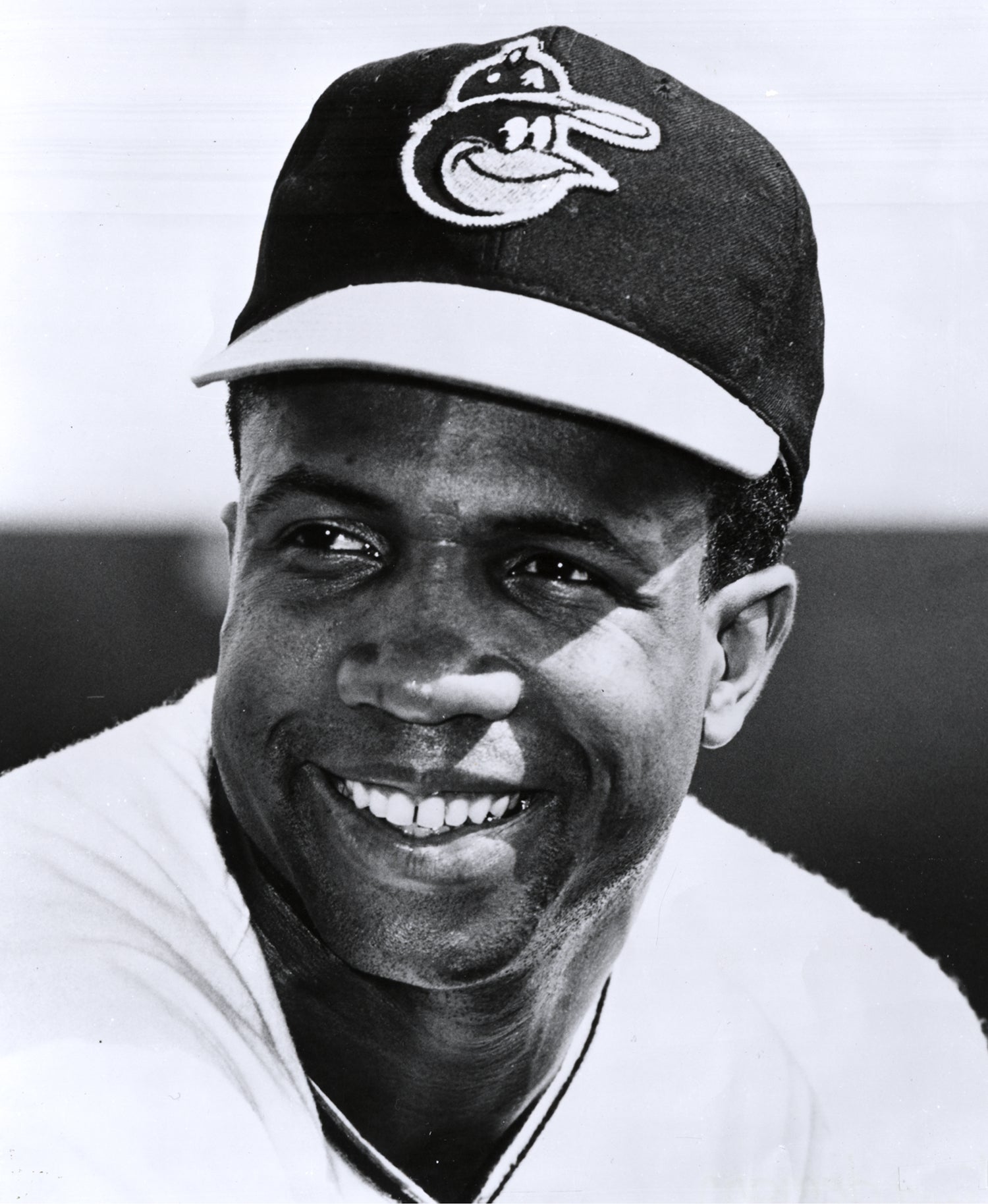

Born Aug. 11, 1938, in Memphis, Tenn., Pinson’s family moved to Oakland, Calif., when he was seven. At McClymonds High School – which also produced big leaguers Frank Robinson and Curt Flood and NBA legend Bill Russell – Pinson established a reputation as a top prospect and signed with the Reds before he turned 18.

In his first full seasons in the minors in 1957, Pinson hit .367 with 40 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs with Class C Visalia of the California League, earning the league’s Most Valuable Player honors.

Invited to Reds’ camp in Tampa, Fla., the following spring, Pinson earned the team’s starting right fielder job for Opening Day.

“I came here thinking I could make the team right now,” Pinson told the Dayton Daily News during camp. “But I realize I’m young, and if I’m sent out again I won’t be unhappy.”

In the second game of the season against Pittsburgh, Pinson hit a third-inning grand slam that proved the difference in Cincinnati’s 4-1 victory. But by May 11, Pinson was hitting .194 and was sent to Triple-A Seattle for more seasoning. In 124 games with the Rainiers, Pinson hit .343 and earned a promotion back to the big leagues in September.

Once clocked at 3.3 seconds from home to first base, Pinson remained one of the game’s top prospects. In 1959, the lefty-swinging Pinson again impressed at Spring Training and won the job as the Reds’ center fielder. This time, Pinson was hitting .349 with 17 RBI at the end of April – ending any threat of a return trip to the minors.

Pinson hit .316 that season with league-leading totals in at-bats (648), runs (131) and doubles (47). He also hit 20 home runs, totaled 84 RBI and 205 hits and stole 21 bases, earning spots in both of that year’s All-Star Games.

Reds coach Wally Moses, an All-Star outfielder with the Athletics, White Sox and Red Sox from 1935-51, said about Pinson: “I honestly believe this kid’s the best 20-year-old ballplayer I’ve ever been associated with.”

Pinson was ineligible for National League Rookie of the Year honors in 1959 due to his 96 at-bats the year before. But he finished 15th in the 1959 NL MVP voting and was 18th in 1960 when he again was named to both All-Star Games en route to a league-leading 37 doubles, 12 triples, 20 home runs, 32 stolen bases and 107 runs scored.

Then in 1961, the Reds won their first NL pennant in 21 seasons behind a lineup led by Pinson and Frank Robinson. Pinson hit .343 with a league-best 208 hits, 16 homers, 87 RBI and 101 runs scored – finishing third in the race for the MVP Award, which was won by Robinson.

Pinson also won a Gold Glove Award for his play in center field, joining Mays and Roberto Clemente as the NL winners in the outfield.

The Reds could not repeat their pennant-winning ways in 1962, but Pinson continued to swing a potent bat – hitting 23 home runs and driving in 100 runs to go with 107 runs scored.

He led the league in hits again with 204 in 1963 and totaled another 204 hits in 1965, continuing to post better totals in almost every category in odd-numbered years. From 1959-67, Pinson averaged .312 with 201 hits and 87 RBI in the odd-numbered years compared to .284 with 178 hits and 80 RBI in the even-numbered campaigns.

Still, most players would have gladly taken Pinson’s “off” years.

Like most other big league batters, Pinson was slowed by The Year of the Pitcher in 1968 – hitting .271 with five homers and 48 RBI. Then on the day after the final game of the 1968 World Series – on Oct. 11, 1968, the Reds traded Pinson to the Cardinals for pitcher Wayne Granger and a younger version of Pinson: Five-tool prospect Bobby Tolan.

“It’s no big shock,” Pinson told the Dayton Daily News following the trade. “I had a feeling early in the year that I was going to be traded. But this is too much – going to the Cardinals. That’s beautiful, just beautiful.”

Pinson was thrilled to be joining a team that had won back-to-back NL pennants and the 1967 World Series. But the Cardinals’ visions of a world-class outfield featuring Lou Brock, Curt Flood and Pinson did not materialize as Pinson hit just .255 with 10 homers and 70 RBI in 132 games.

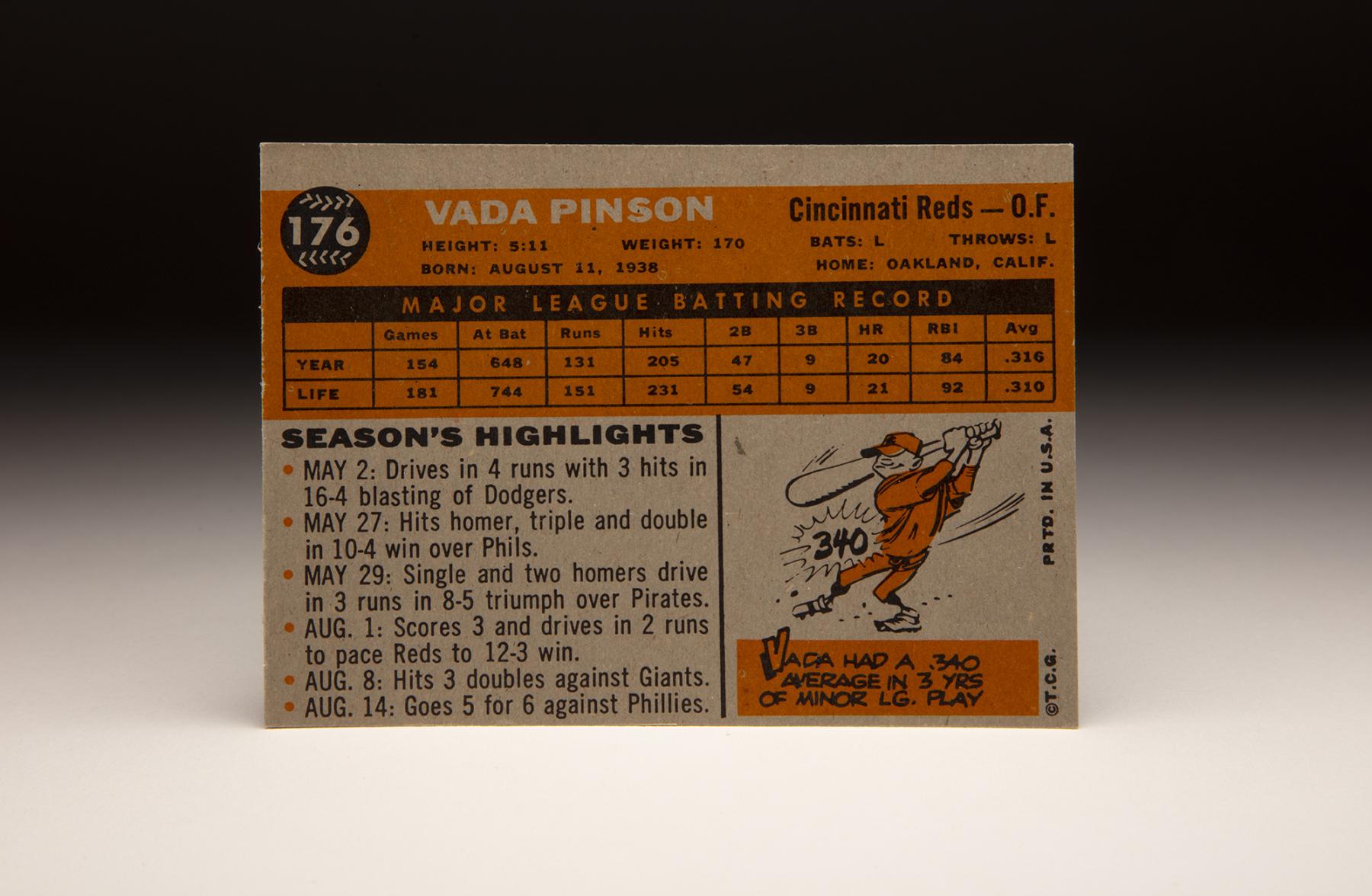

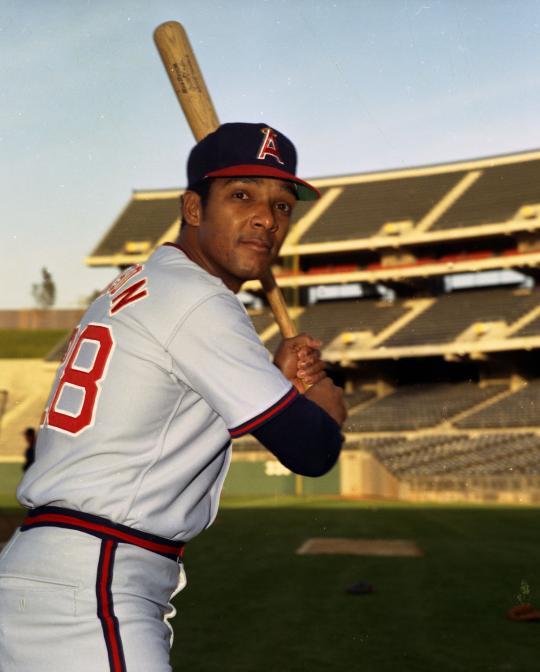

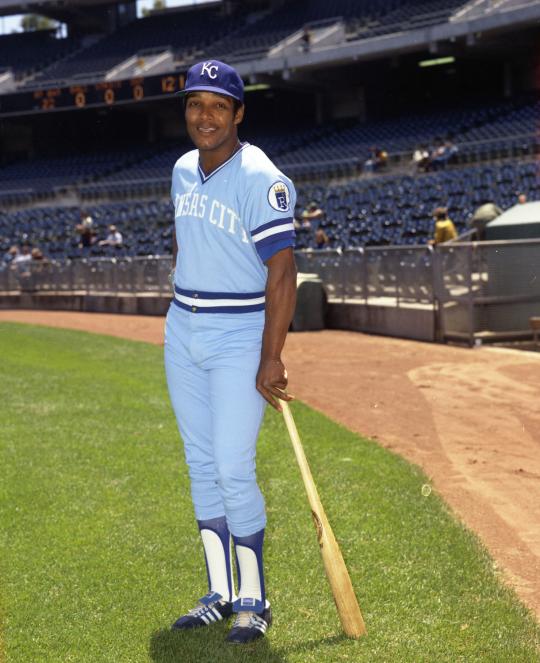

On Nov. 21, 1969, the Cardinals traded Pinson to the Cleveland Indians for José Cardenal in a deal that had been rumored for weeks. Pinson bounced back to hit .286 with 24 homers and 82 RBI for the Indians in 1970, but totaled only 11 homers and 35 RBI in 1971. He spent his final four big league seasons with the Angels and Royals, retiring after the Brewers released him in Spring Training in 1976.

“Vada looked like he had slowed down,” said Brewers manager Alex Grammas told United Press International.

But few players ever played as fast as Pinson, who finished his career with a .286 batting average, 2,757 hits, 256 home runs and 305 stolen bases. He is one of only nine players in history with at least 2,700 hits, 250 home runs and 300 steals. And of those nine, only Willie Mays, Barry Bonds, Álex Rodríguez and Derek Jeter topped Pinson’s .286 batting average.

Pinson served as a respected hitting instructor and coach following his playing days with the Mariners, White Sox, Tigers and Marlins. He passed away on Oct. 21, 1995, after suffering a stroke a few weeks earlier.

“Vada never got the attention he deserved,” Sparky Anderson, who utilized Pinson as a trusted coach with Detroit, told the Cincinnati Enquirer when Pinson passed. “He obviously didn’t have the power of a guy like (Mickey) Mantle, but in every other way he was like Mantle.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum