- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1959 & 1972 Topps Norm Cash

#CardCorner: 1959 & 1972 Topps Norm Cash

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

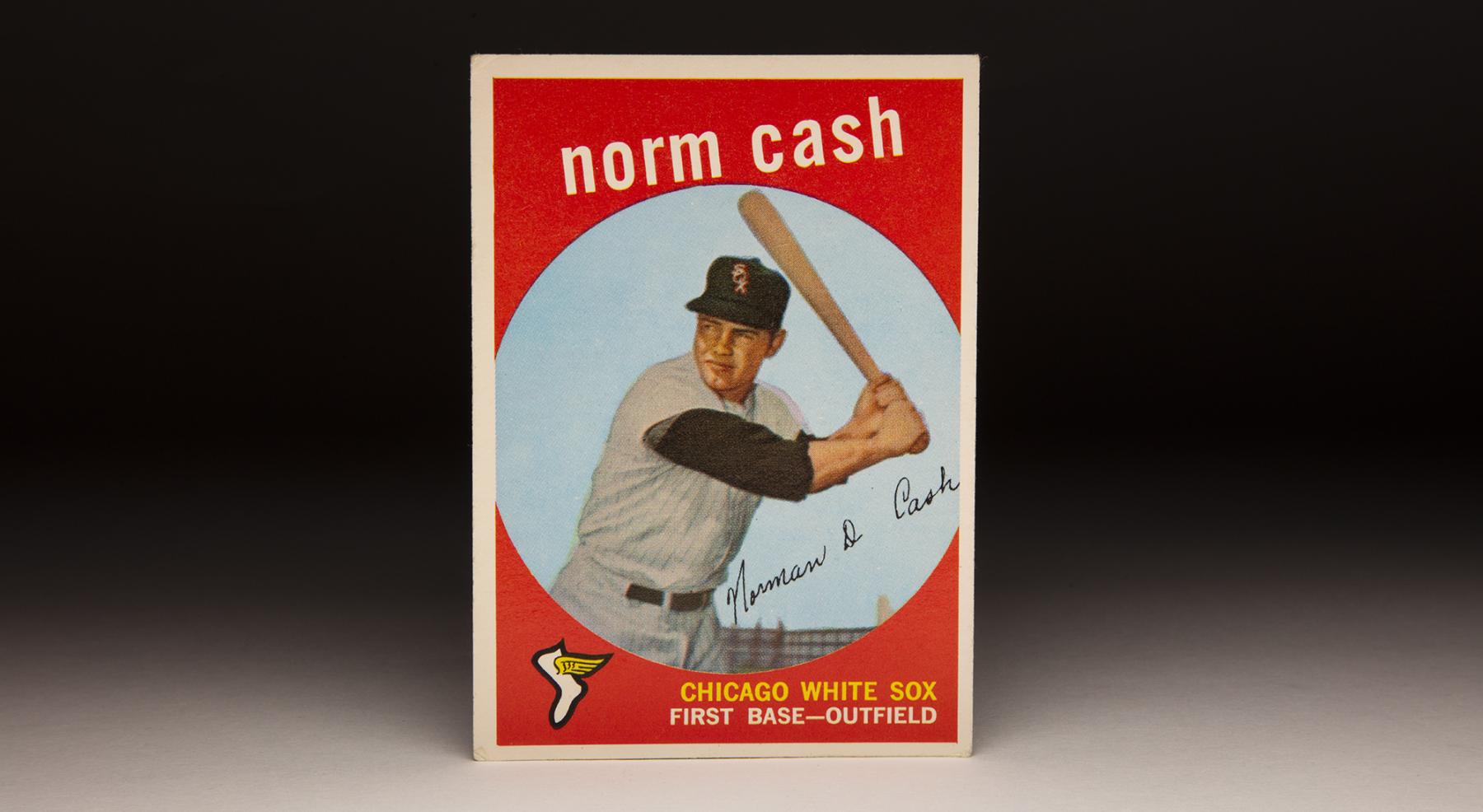

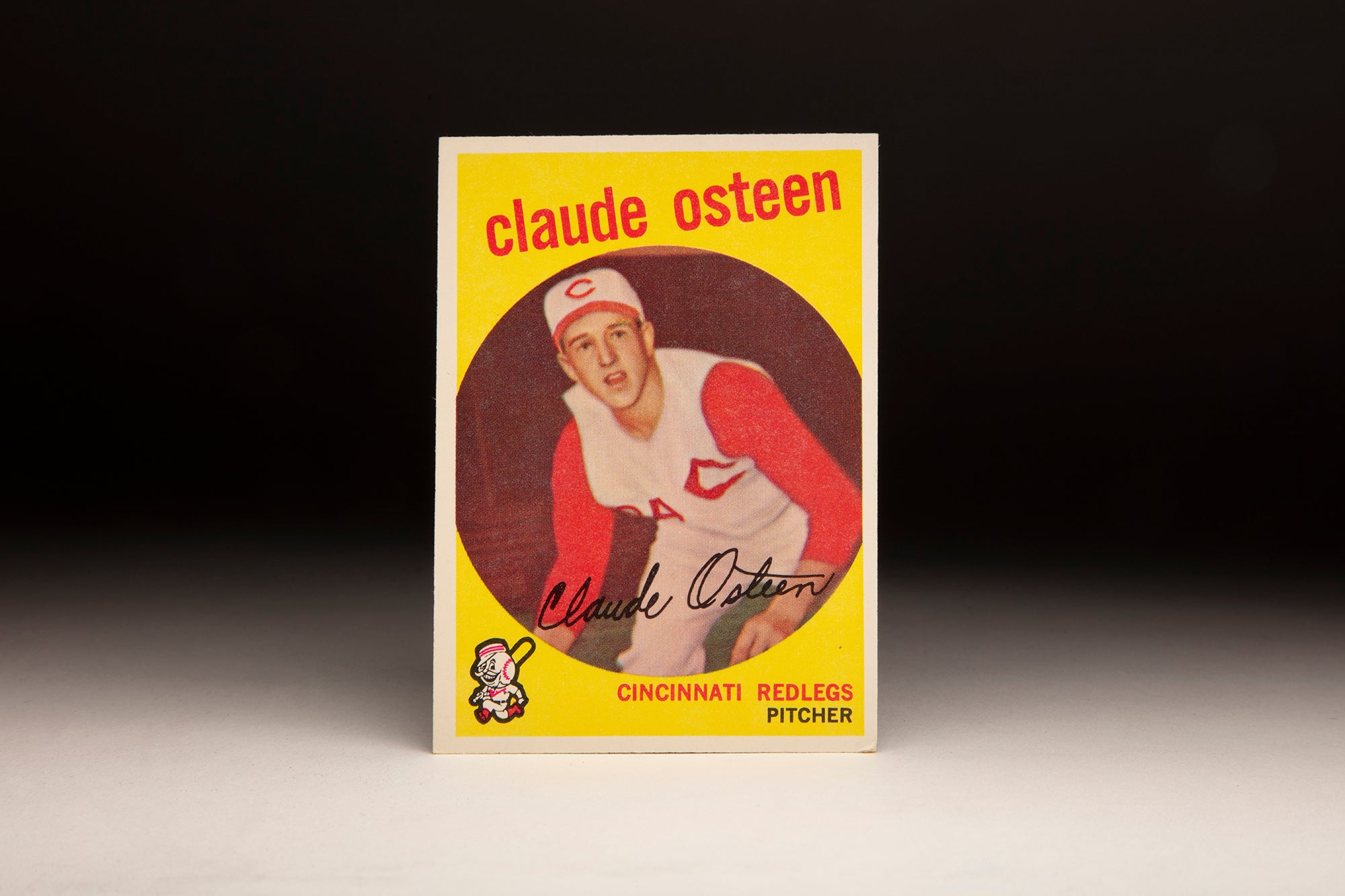

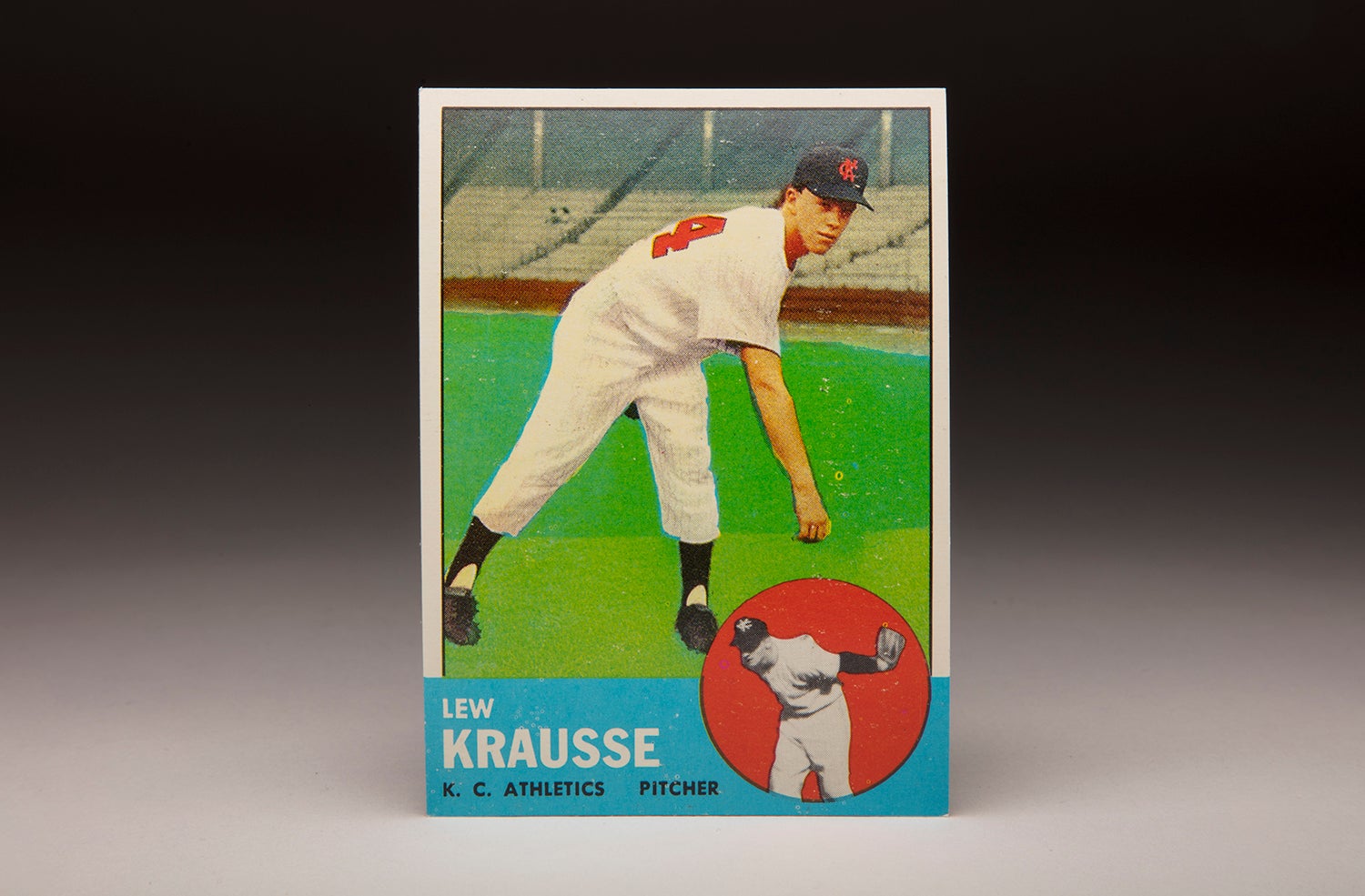

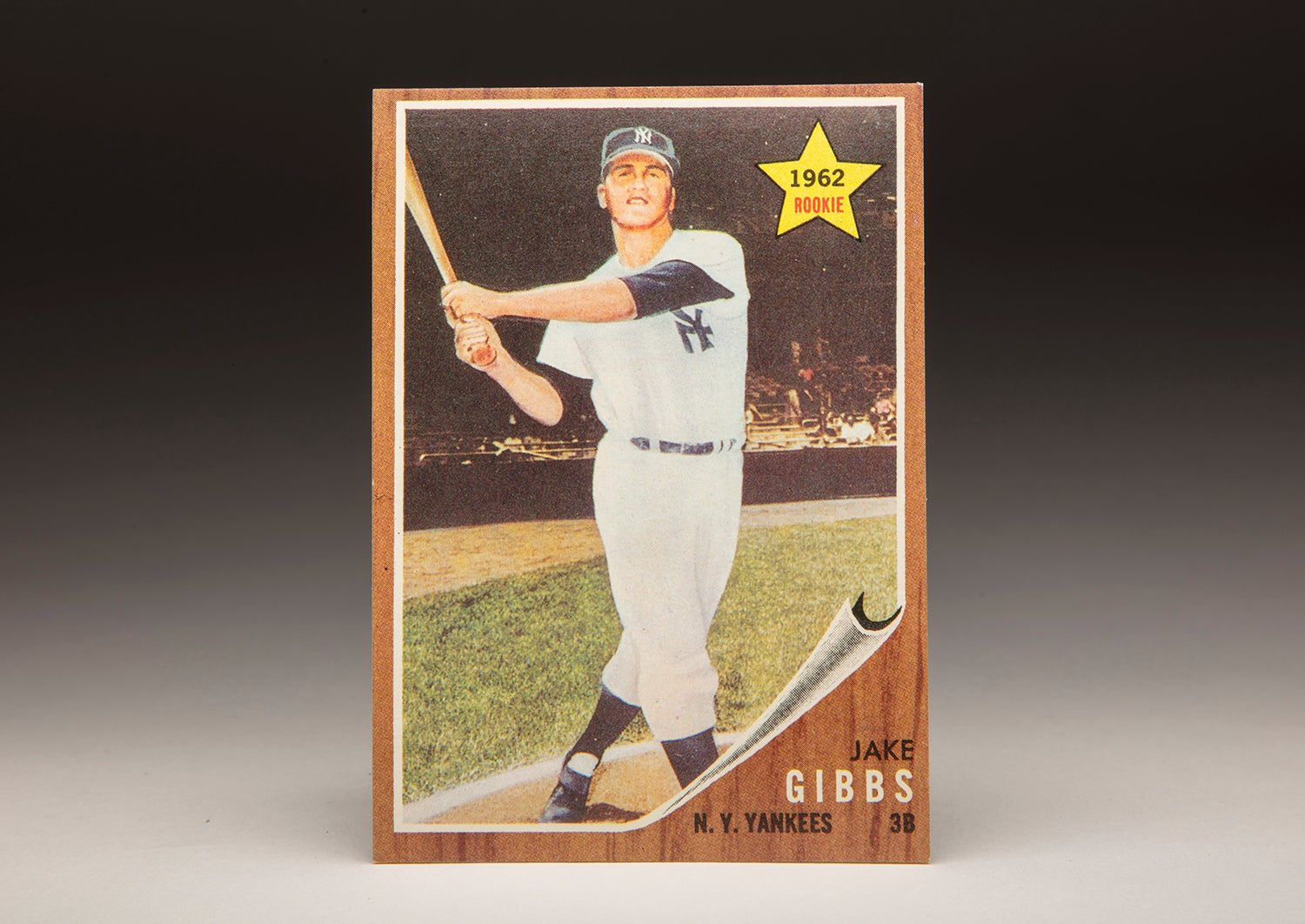

Much like Jake Gibbs’ 1962 Topps card and Lew Krausse’s 1963 card, there is something bizarrely surreal about Norm Cash’s 1959 Topps card.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

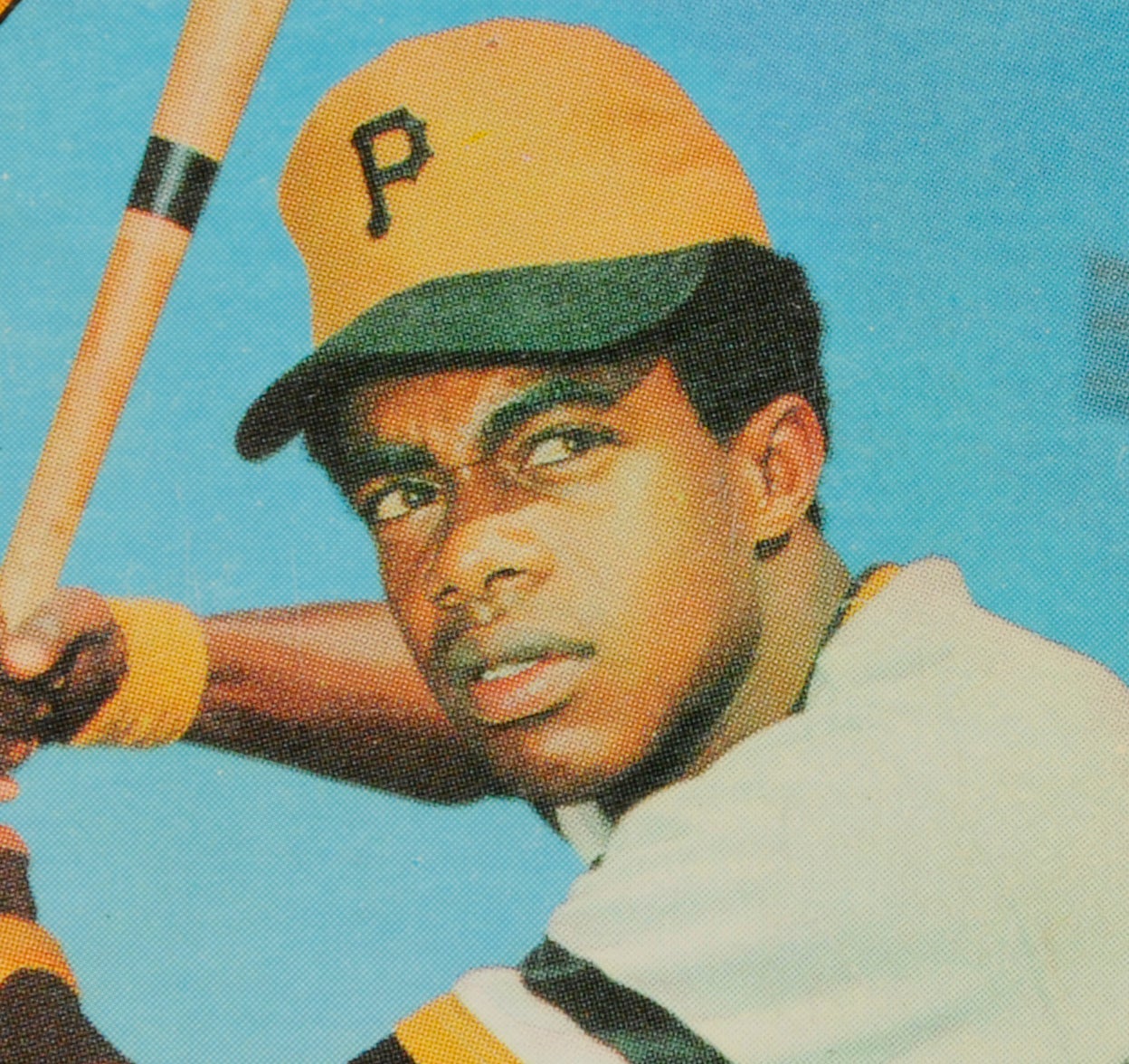

It’s not just that Cash’s Chicago White Sox uniform has been completely airbrushed, a situation caused by the fact that he appeared in only eight games for the Sox in 1958 but not once when a photographer could capture his image for a baseball card. Beyond that, it appears that Cash’s face and arms have been airbrushed too, or perhaps they have been simply colorized from a black-and-white photo.

Either way, Cash looks almost cartoonish here, as if he’s been drawn onto a card, and not actually photographed.

Even the blue sky background looks surreal, or put more bluntly, completely fake. The sky has an odd hue, one that is not natural and not what we would normally expect when viewing an outdoor scene at a major league ballpark.

In a way, the offbeat nature of the card is most fitting for a player like Cash, one of the most colorful figures of the 1960s and early 70s. There was very little about Cash that was routine and ordinary: He was a larger-than-life character who cut his own down-home style, while making his teammates laugh with his sense of humor and succession of pranks. He did all of this while living the fast life. Few ballplayers have ever had as good a time as Stormin’ Norman Cash.

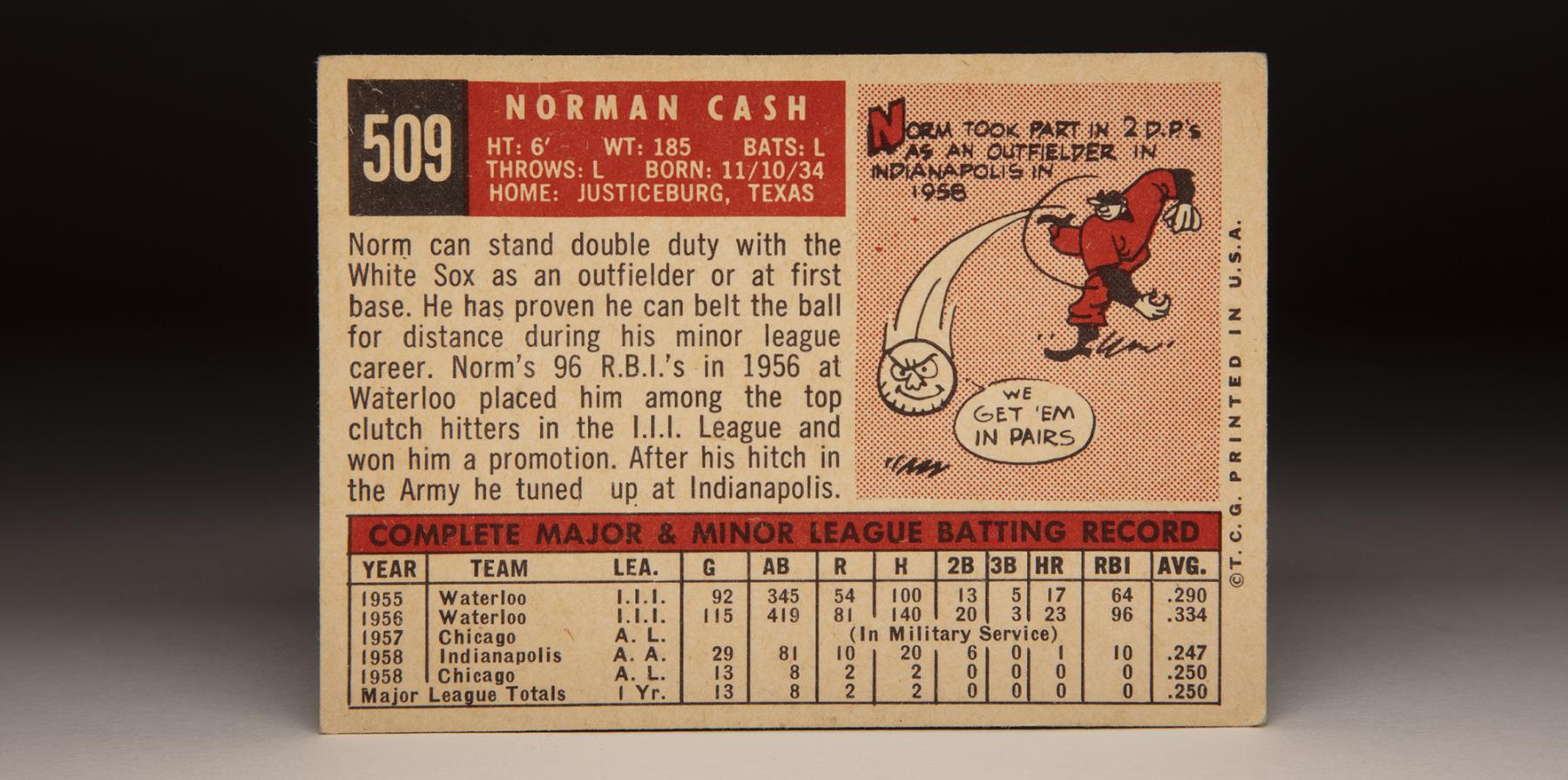

Cash would turn into a standout first baseman and power hitter, but his career almost took a turn to the gridiron. The NFL’s Chicago Bears drafted him out of college and made him an offer, but Cash turned it down and decided to opt for baseball. He signed with another Chicago team – the White Sox – who brought him up to the big leagues in 1958 and ’59. Appearing in a combined 71 games, he did little of note for Chicago, though he did show a good eye at the plate in ’59, walking 18 times against only nine strikeouts.

After that season, the Sox included him in a deal with the Cleveland Indians, part of a multi-player trade for Minnie Minoso. But Cash would never appear in a single game for the Indians. The following April, just before Opening Day, Indians general manager Frank “Trader” Lane pulled off a one-for-one deal with the Detroit Tigers. In exchange for third baseman Steve Demeter, Lane gave up Cash. It would turn out to be one of Lane’s greatest mistakes – and a boon for the Tigers. Demeter would appear in only four games with the Indians, and never again play in the major leagues, while Cash would become a mainstay in Detroit for the next 15 seasons.

After debuting for the Tigers in 1960 and posting an OPS of .903, Cash put together a career season for the ages in 1961 – although it was overshadowed by the remarkable home run race involving Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. While the “M and M Boys” chased Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, Cash compiled overall numbers that were just about as impressive. He won the batting crown with a .361 average and totaled other career bests in many offensive categories, including home runs (41), slugging percentage (.662) and on-base percentage (.487.) He also drew a remarkable 124 walks against only 85 strikeouts. Cash would finish third in the American League MVP race, but in most other seasons, his numbers would have been good enough to bring home the trophy.

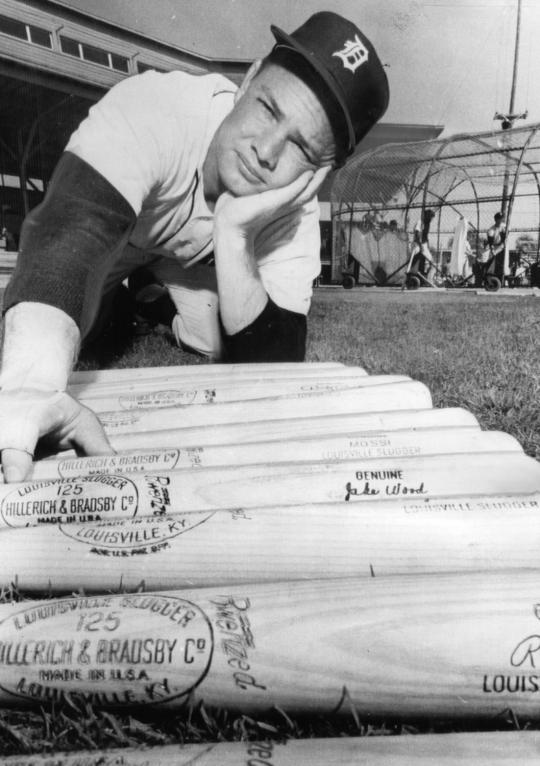

Later in his career, Cash would reveal that his career season of ‘61 came with some “assistance.” In an article that appeared in the Sporting News, Cash admitted that he played the entire 1961 season – not to mention other long stretches of his career – while using a bat filled with cork. Cash explained that he would drill a hole in the top of his bats, then fill the cavity with a mix of cork, sawdust, and glue.

The doctored bat became his weapon of choice, though no opposing team or umpire actually caught him in the act of cheating. (While this was clearly against the rules, the scientifically-savvy reader will note that corking the bat is not believed to increase the flight of the ball off the bat. While corking increases bat speed, it also lessens the mass of the bat, and that is believed to cancel out any additional force.)

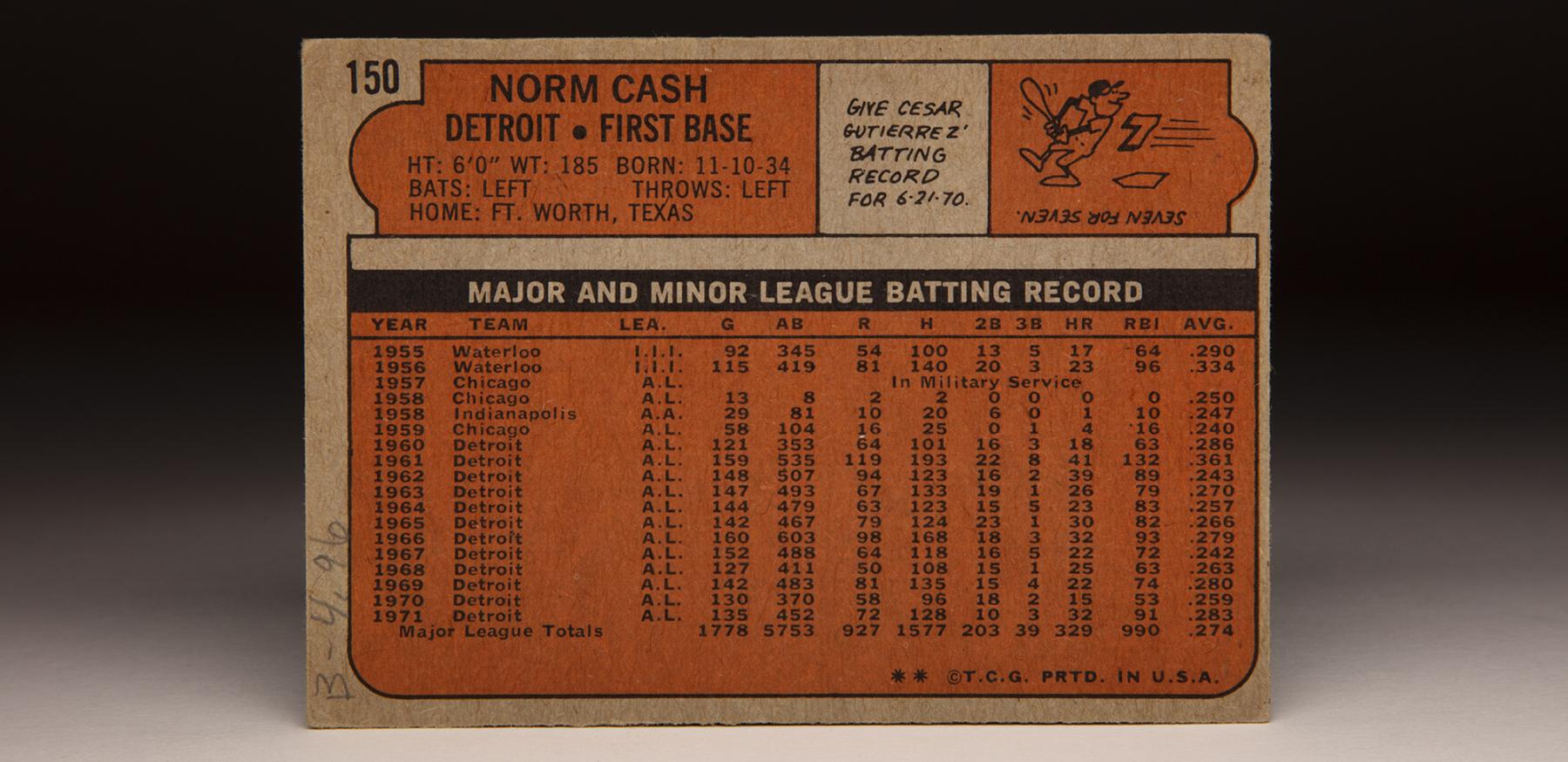

Cash would never again match his 1961 performance, but would remain a mainstay for the club throughout the 1960s, while also emerging as one of the most likeable players in the Tigers’ clubhouse. From 1962 to 1966, in an era that saw run-scoring fall off dramatically throughout the major leagues, Cash averaged 30 home runs per season and didn’t post an OPS of any lower than .804. After a bit of a downturn in 1967, Cash bounced back during the Year of the Pitcher, hitting 25 home runs while registering an OPS of .816. Receiving some back-of-the-ballot support in the league MVP race, Cash helped the Tigers run away with the 1968 American League pennant.

Along with Al Kaline, Willie Horton and Bill Freehan, Cash was one of the core players on the ’68 Tigers. Facing the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, the Tigers found themselves down three games to one. That’s when Cash stepped in, according to his Tigers teammate, left-hander Jon Warden.

“Well, I’ll tell you, Cash was always the ‘go’ guy. He was sort of the leader,” Warden told me during a Hall of Fame Classic at Doubleday Field. “I’ll tell you, [it’s] the fifth game of the World Series. And Cash is in the locker room saying, ‘We got ‘em right where we want them. They’re so tight over there… This is gonna be great for us, because we’re gonna win one for the home team.’ ”

The Tigers won the next three games to take the Series. And Cash did more than provide the rallying cry. Over the seven-game series, Cash batted .385, slugged .500 and collected five RBI. Cash’s exploits became somewhat lost amidst the pitching exploits of Mickey Lolich, who won all three of his starts against St. Louis, but there’s little doubt that the Tigers would have fallen short of a title without Cash’s prolific slugging.

After the glory of 1968, Cash and the Tigers endured a post-Series hangover in 1969 and ‘70. Entering the 1971 season, Cash was now 36 years old, making some skeptics wonder if he had much left in his aging body. Cash answered the critics with an enormous bounceback season, his best since the career year of 1961; he finished second in the American League with 32 home runs, made the All-Star team, placed 12th in the MVP voting and earned the league’s Comeback Player of the Year Award. Having already won the award in 1965, Cash became the first man in history to win the comeback award on two occasions.

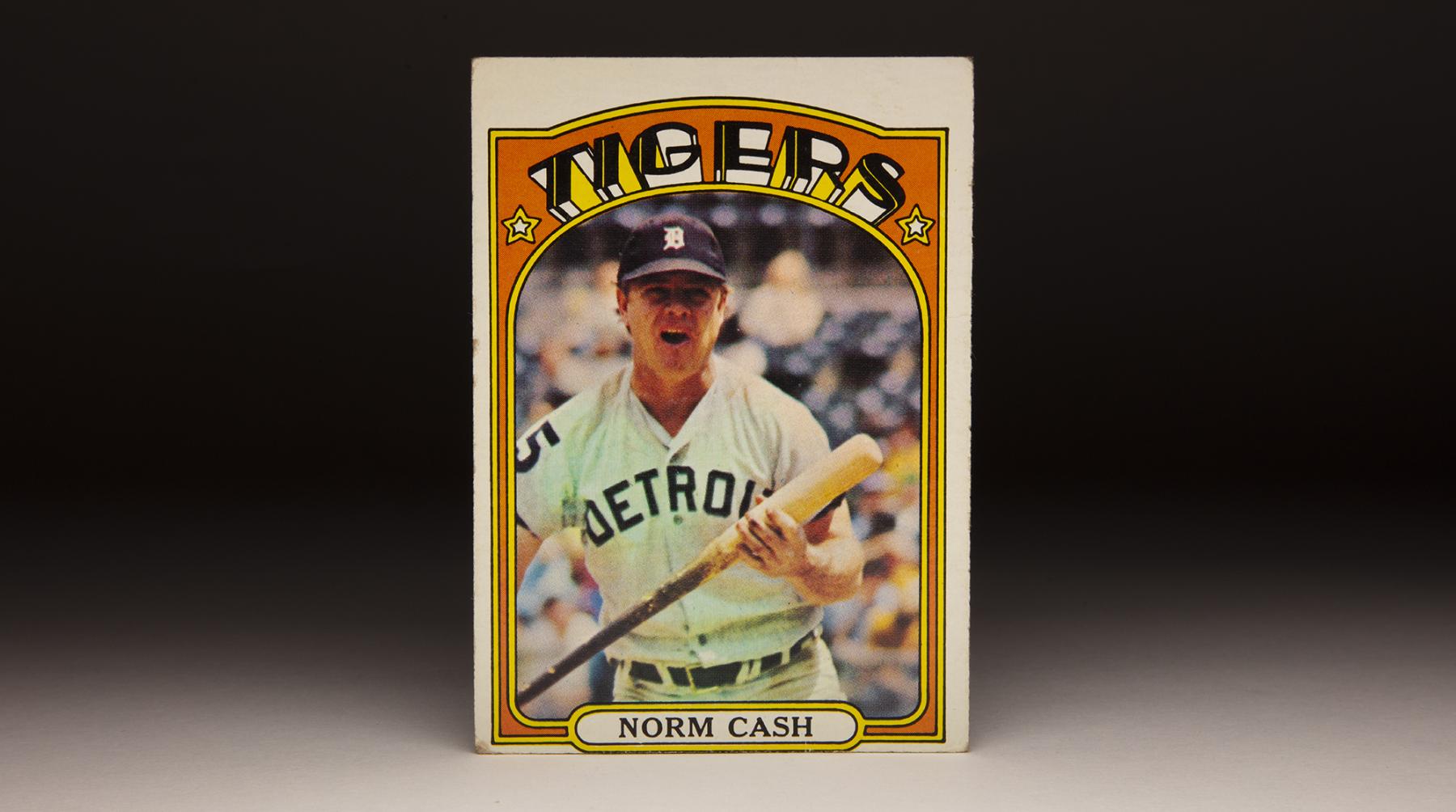

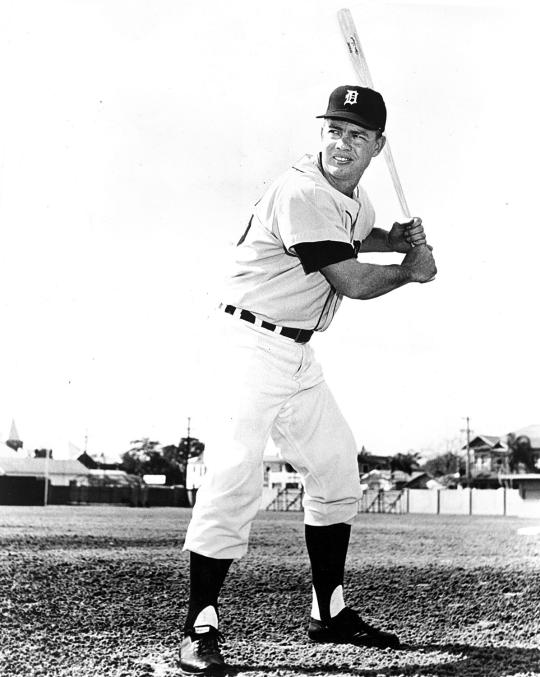

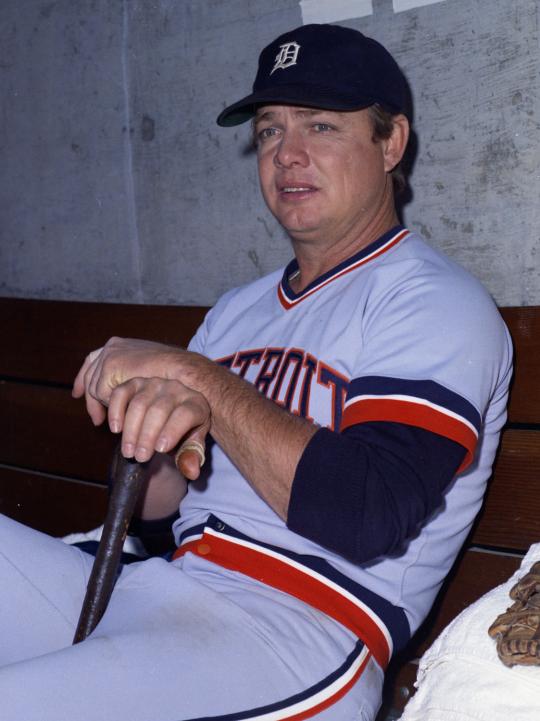

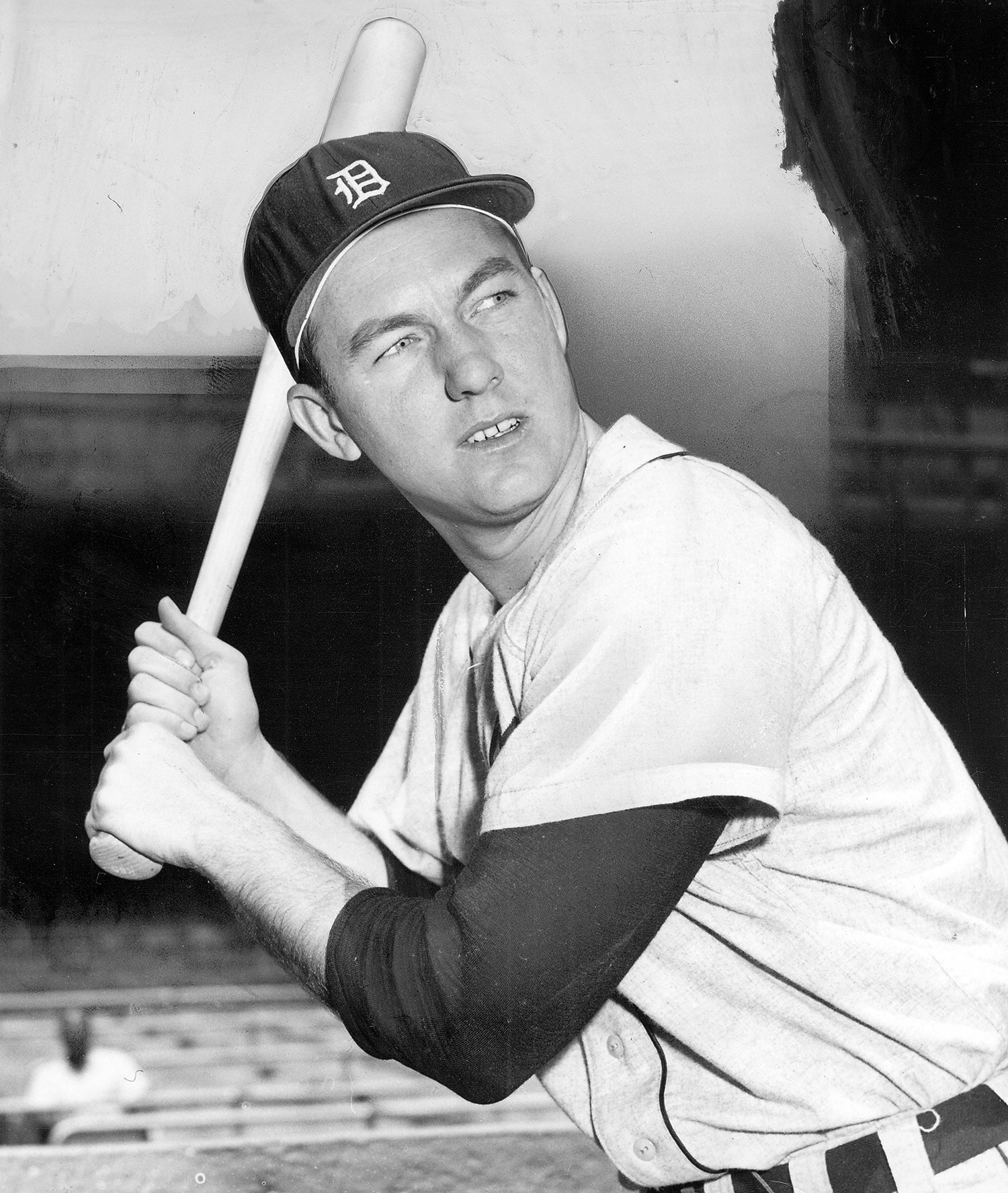

Fresh off the rejuvenation of ‘71, Topps released his 1972 card during the spring. The card shows Cash at his offbeat best, wearing a cap to the plate and not a batting helmet. This was actually nothing new, because Cash had played his entire career without using a helmet at bat. Like two other veterans of the era, Bob Montgomery and Tony Taylor, Cash became one of the last holdouts in responding to Major League Baseball’s 1971 rule that made helmets mandatory. Under the rule’s grandfather clause, Cash wore a cap with a protective liner underneath. When Cash retired in 1974, only Montgomery and Taylor remained as players who continued to bat without a protective helmet.

The 1972 card also shows Cash holding a bat that is clearly illegal, not necessarily because of cork, but because it has so much pine tar that it exceeds the 18-inch limit. It’s a bat that easily could have created controversy, ala the 1983 Pine Tar Game, but it apparently escaped detection from the umpires or opposing teams.

Illegal bat or not, Cash’s production fell off in 1972, but not enough to prevent him from making another All-Star team, hitting 22 home runs, and helping the Tigers win the American League East in a strike-dampened season. Thanks to the unbalanced schedule that resulted from the early-season players’ strike, the Tigers played one more game than the Boston Red Sox and finished a half-game ahead of them for the Eastern Division crown. According to the agreement reached in ending the strike, no makeup games would be allowed in erasing potential discrepancies.

In 1972, Cash saved his best hitting for the Championship Series against the Oakland A’s. He put up an OPS of .820 in the ALCS, but the Tigers lost to the eventual world champions in a heart-wrenching five games.

The following season, Cash made some bizarre bat-related news. With Nolan Ryan in the midst of throwing his second no-hitter for the California Angels, Cash decided to walk to the plate without a bat, instead carrying what appeared to be a strangely-shaped piece of wood. Legendary Tigers play-by-play man Ernie Harwell described the item as a “piano leg,” but it was actually a table leg, taken from a piece of furniture in the Tigers’ clubhouse.

The owner of an offbeat sense of humor, Cash had every intention of using the table leg, figuring that it might change his luck against the impenetrable Ryan. But Cash was forced to discard the makeshift “bat” by home plate umpire Ron Luciano, a colorful sort himself, but not one to allow a blatant violation of the rules. Luciano told Cash to discard the table leg and replace it with a regulation piece of wood. Doing as he was told, Cash found a real bat – and proceeded to strike out on three pitches.

Earlier in his career, Cash had tried to pull another fast one on the umpires, this time in a very different way. Playing in a game against the White Sox at Comiskey Park, Cash was the runner at first base when heavy rains hit and forced the umpires to impose a rain delay. When play resumed after a lengthy stoppage, Cash took his place on the bases – but this time at second base.

When the umpire questioned him about it, Cash replied, “I stole the base during the storm.” The umpire immediately told Cash to return to his original base. Even If Cash couldn’t gain an advantage on the basepaths, at least he could extract a humorous moment out of it.

Cash’s colorful manner extended to life away from the ballpark. Cash earned a reputation for drinking, with beer being the beverage of choice. From 1971 to 1973, he developed a particularly strong friendship with Tigers pitching coach Art Fowler. Sharing a similar sense of humor, the pitching coach and first baseman spent hours together away from the ballpark, sometimes joined by manager Billy Martin. According to numerous Tigers fans, Cash, Fowler and Martin closed a number of taverns during their years together in Detroit.

In his final two seasons with the Tigers, Cash took on the role of a platoon player, sharing time at first base with Frank Howard in 1973 and Freehan in 1974. During the latter season, Cash saw his batting average fall into the .220 range. On Aug. 7, Tigers general manager Jim Campbell called Cash into the office and told him that he was being given his release. Cash wanted to finish out the season with the Tigers before stepping aside, but the release ended his career with little fanfare.

After the Tigers cut him loose, Cash continued to dabble in broadcasting, which he had started to pursue as a player. He hosted his own program, “The Norm Cash Show,” and served as a broadcaster for one season of ABC’s Monday Night Baseball in 1976. Cash also joined a professional softball league, playing for a local team known as the Detroit Caesars. All the while, Cash continued to regale friends and fans with stories from his days in Detroit, both on and off the field.

Sadly, Cash’s health began to decline shortly after his playing days came to an end. In 1979, he suffered a massive stroke, which affected his speech and ultimately ended his broadcasting career. And then a few years later, a greater tragedy struck.

On Columbus Day Weekend of 1986, Cash went to dinner with his wife and some friends on Beaver Island, located in northern Lake Michigan. When dinner ended, Cash made his way to a local dock to check on his private boat. Wearing cowboy boots on a slippery dock soaked by rain, Cash lost his footing and fell into the cold water. The next day, his body was found floating in St. James Bay. Cash was only 51.

As if his early death wasn’t tragic enough, an autopsy determined that Cash was legally drunk at the time of the accident.

But it also shouldn’t detract from the legacy of a player who was beloved by his team’s fan base, and universally liked by his teammates. As former Tigers pitcher Jerry Casale told sportswriter Maxwell Kates, “on a team with so many friends, there was no one nicer than Norm Cash.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame