- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1959 Topps Claude Osteen

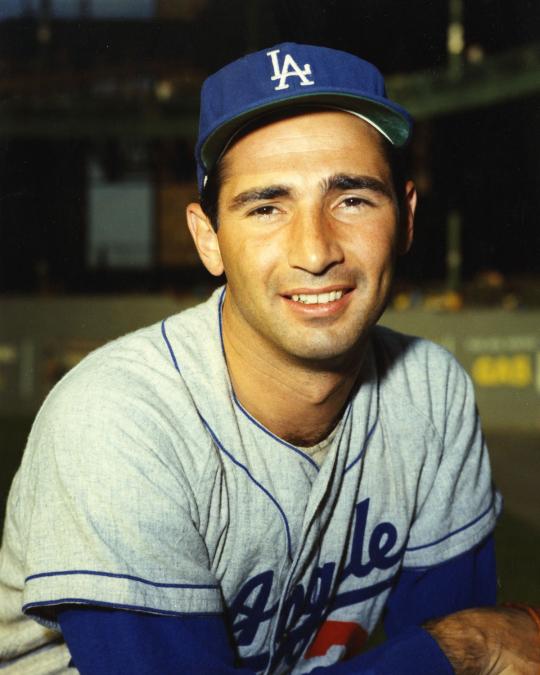

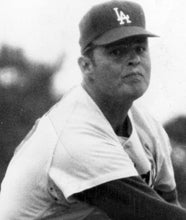

#CardCorner: 1959 Topps Claude Osteen

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

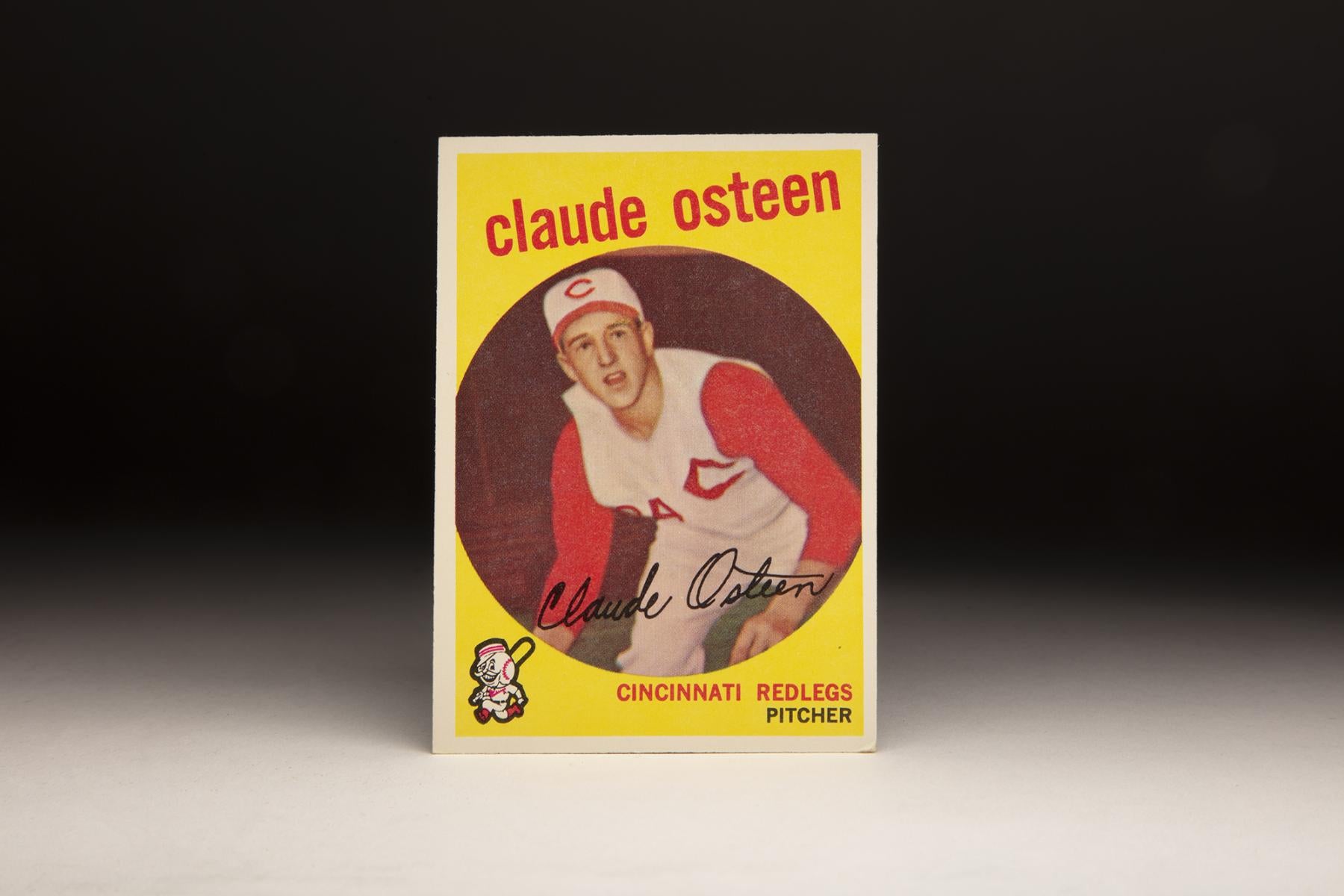

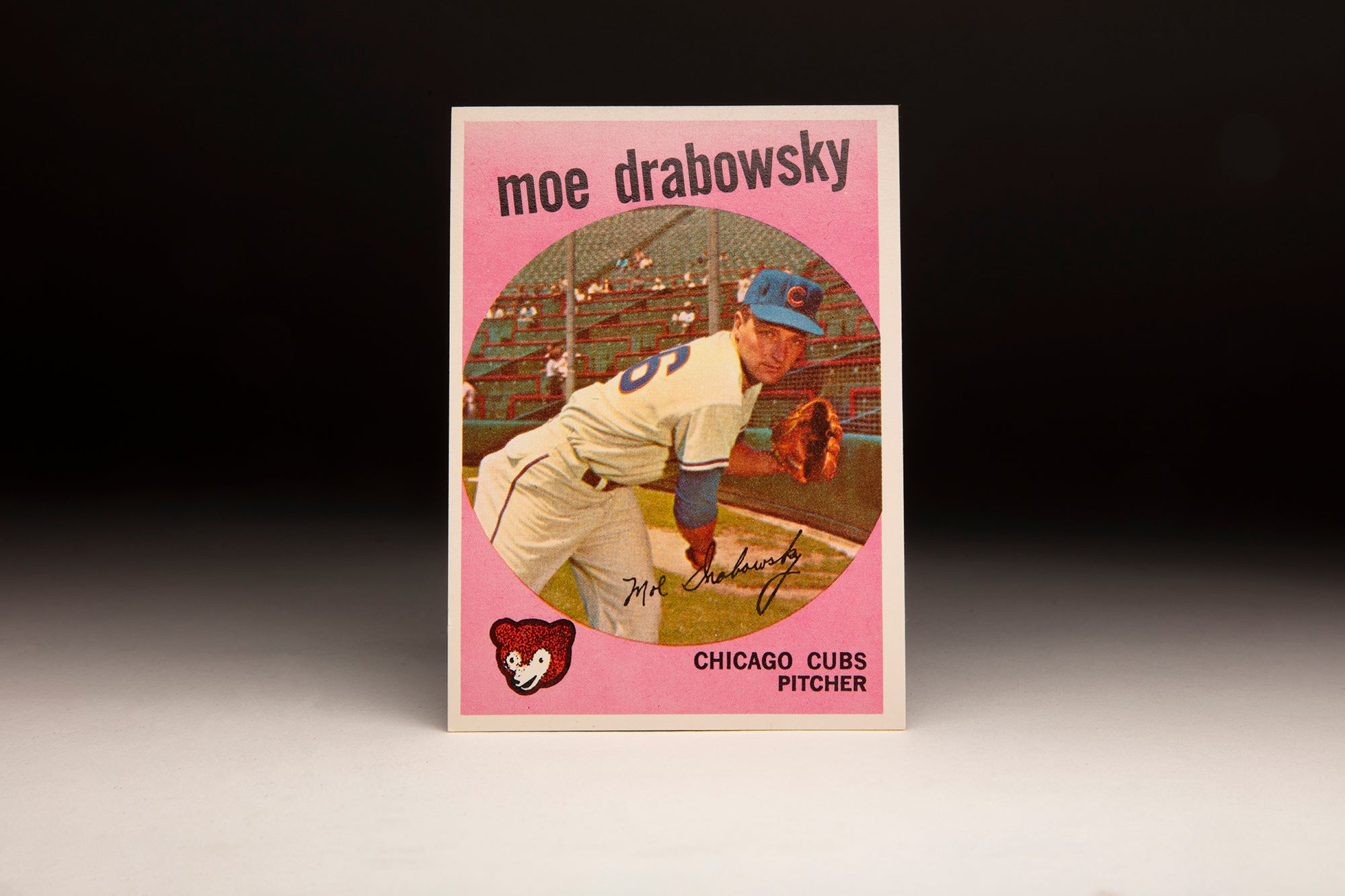

There’s a lot to unpack when it comes to Claude Osteen’s 1959 Topps card.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The yellow frame, seen on many of the ’59 cards, is quite eye-popping. Then there is Osteen’s physical appearance. He looks like he’s about 12 years old here. (He was only 18 at the time, but even that age seems like a stretch.) He also does bear an uncanny resemblance to famed actor Jim Nabors, which perhaps explains Osteen would eventually be given the nickname of “Gomer,” the character that Nabors played from 1962 to 1964 on The Andy Griffith Show before earning his own television series.

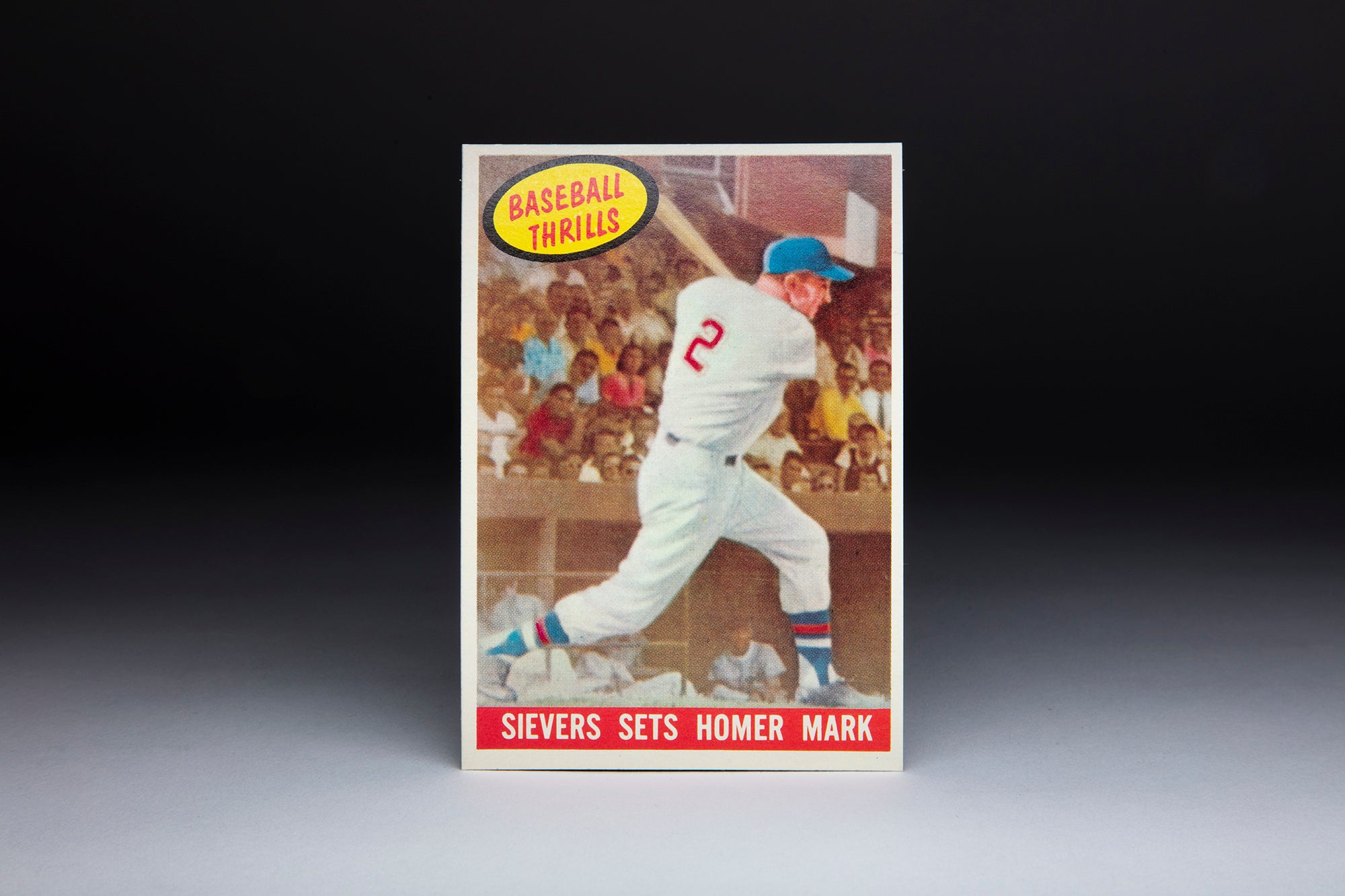

The team nickname also stands out on the ’59 card. Osteen’s team is not listed as the Cincinnati “Reds,” but rather the Cincinnati “Red Legs.” The change in names stemmed from the 1950s political movement known as McCarthyism, an effort led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, who accused a number of politicians and celebrities of being members of the communist party.

In Hollywood, over 300 actors and directors were placed on an unofficial blacklist and denied subsequent work because they were suspected of being communists. McCarthyism affected citizens who were not celebrities, too. For example, libraries in Indiana were pressured by anti-communists to remove the iconic book, Robin Hood, because of its favorable view of “spreading the wealth.” Those opposed to communism believed that the book encouraged an ill-conceived economy and way of life.

Baseball was not excluded from this political development. In 1954, the Cincinnati franchise reacted to the situation by changing its nickname from “Reds,” a word clearly associated with communism, to “Red Legs.” By 1956, the word “Reds” was completely removed from the team’s uniform, replaced by a large letter “C.” That season marked the first time since 1912 that Cincinnati’s home uniform failed to include the team’s nickname.

The disuse of Reds continued throughout the late 1950s and into the early 1960s. By 1961, with the era of McCarthyism now over, the Reds restored the club’s original nickname and its use on the team uniform.

Few ballplayers of the era offered public comment on the issue of McCarthyism. For a young player like Osteen, who was still trying to establish himself, there was little incentive to take a stand one way or another on controversial political matters. He was simply trying to prove that he belonged in the major leagues.

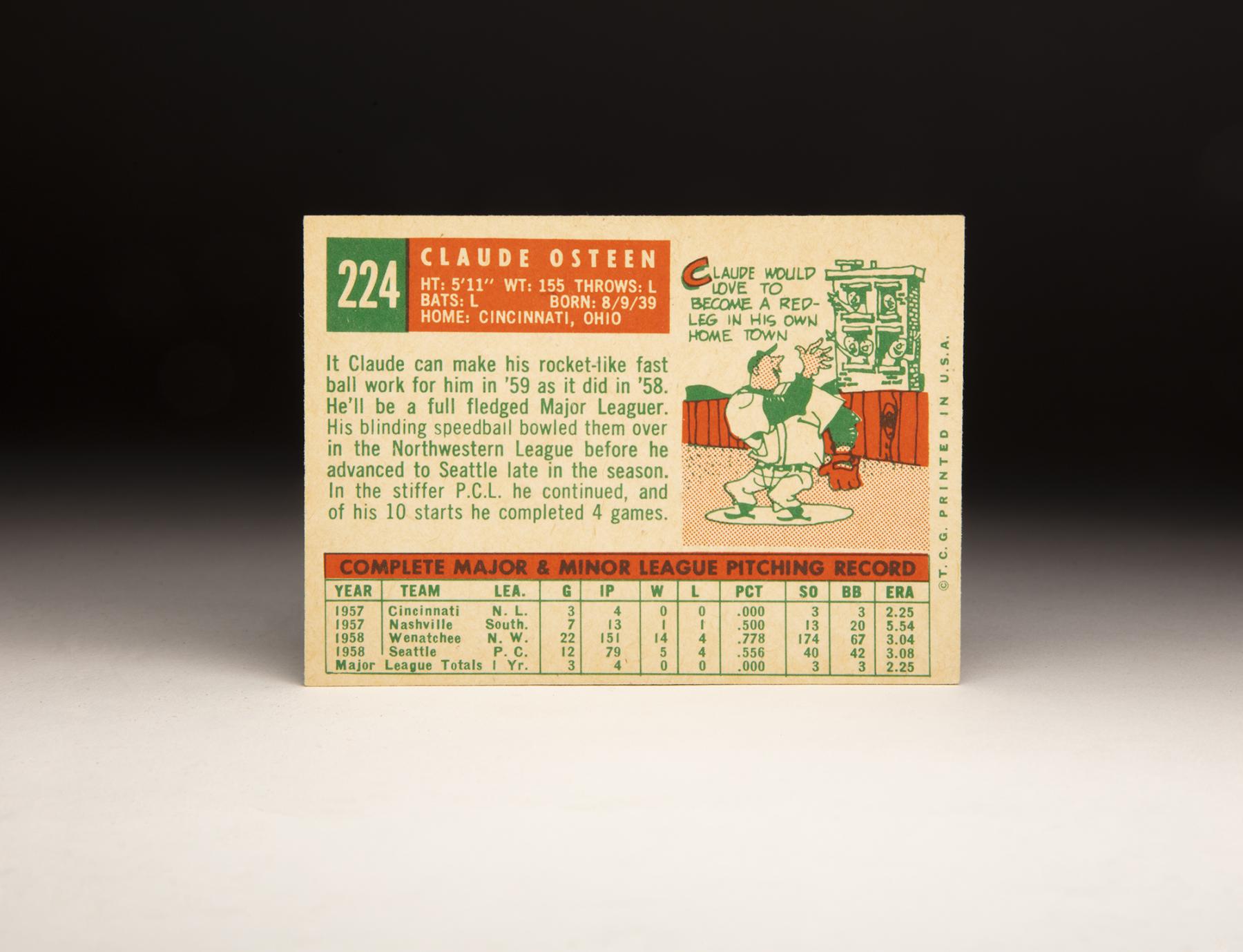

Osteen had pitched only briefly for the Reds in 1957, the season in which he originally signed with the franchise and then debuted in the major leagues. As an amateur, Osteen was a highly desired young pitcher, even though he stood only 5-foot-10. At least 11 teams showed interest in him, as did three colleges that offered scholarships, but the Reds won the bidding war in ’57.

Osteen did not pitch at all in the major leagues in 1958, but Topps still saw fit to include him in its new set of cards in 1959. He would appear in all of two games for the Reds in ’59, and those games did not go well; he walked nine batters in seven innings and sported an ERA of 7.04.

Osteen’s troubles would continue in 1960, when he struck out only 15 batters while walking 30 as a little-used reliever. Plagued by wildness and lack of command, he then spent most of 1961 in the minor leagues.

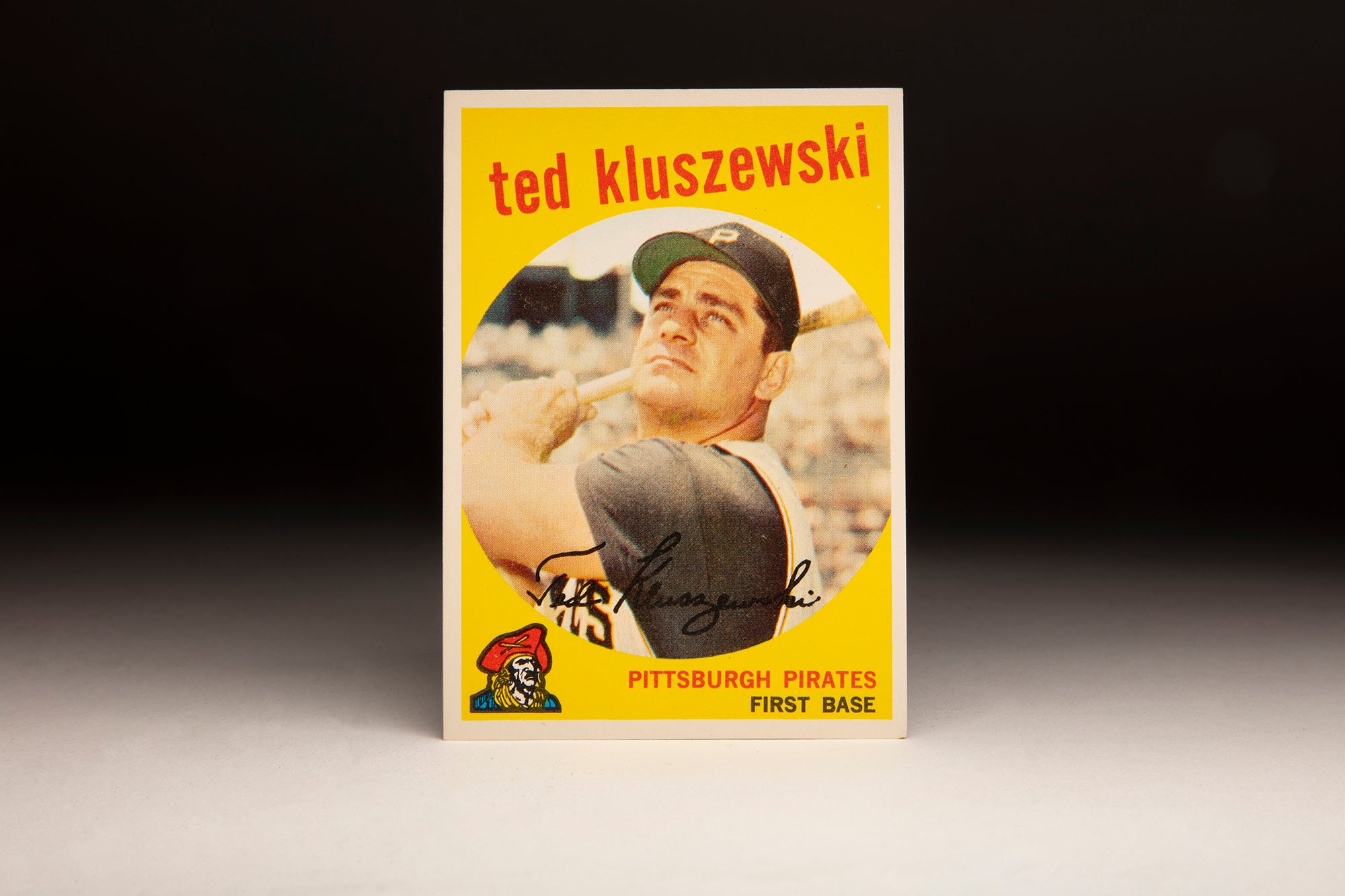

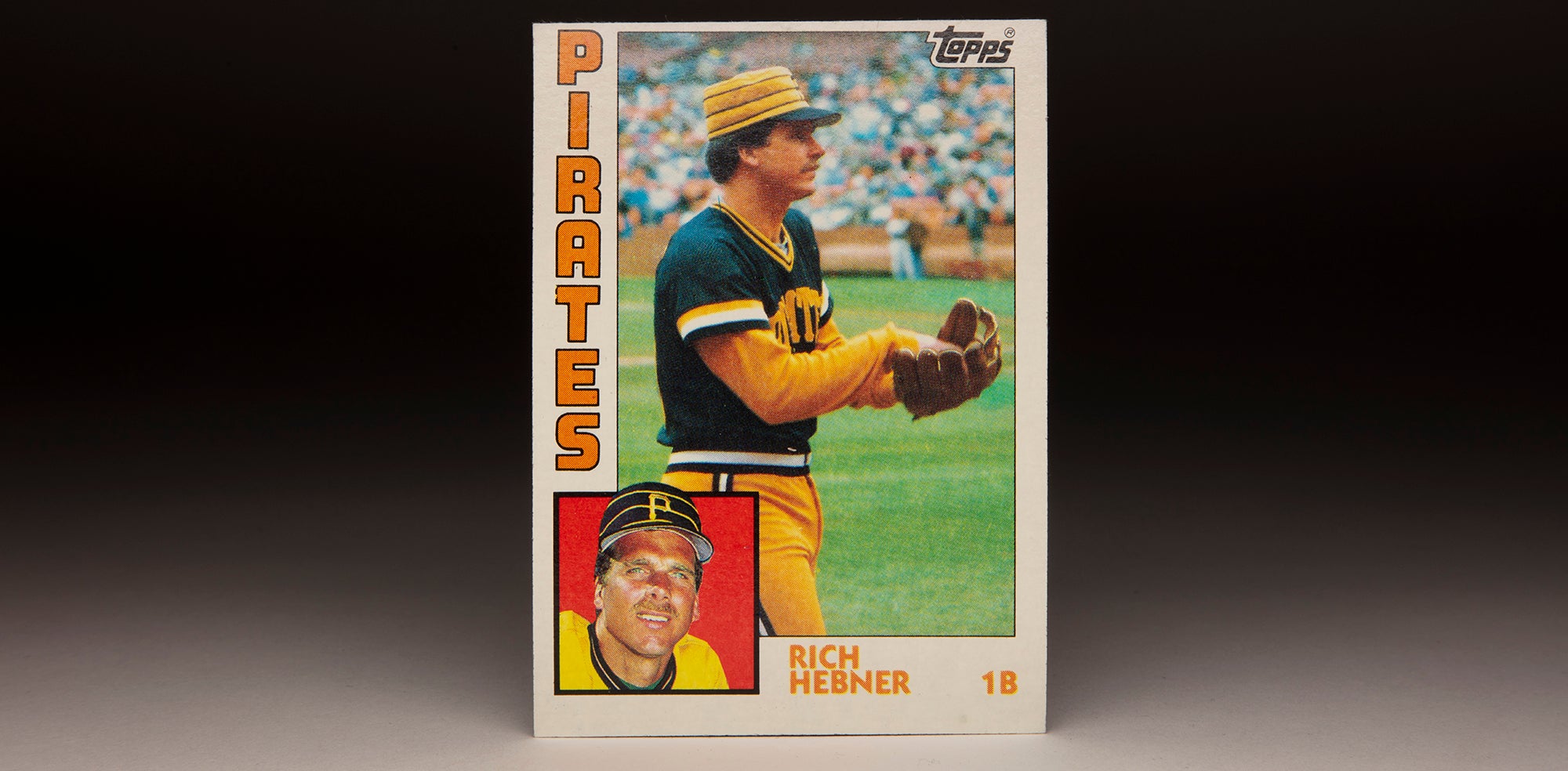

The Reds finally gave up on Osteen late in the ’61 season. In September, they traded him to the Washington Senators for a player to be named later, which turned out to be pitcher Dave Sisler, the son of Hall of Famer George Sisler.

The trade became the break that Osteen needed. Desperately short on pitching, the Senators made Osteen one of their four starters. A pitcher who was uncomfortable working out of the bullpen, Osteen had longed for a role as a starter. Now he had the chance.

After making three starts for the Senators late in 1961, Osteen moved into the rotation on a regular basis in 1962.

He lost his first four starts, but then began to settle in. He missed some time with injury, but pitched well over the second half of the season, finishing with a 3.65 ERA and an 8-13 record. He also curbed his wildness, issuing only 47 walks in 150 innings.

The 1963 season would represent something of a breakout for Osteen. He improved his control, to the point where he could hit his catcher’s target with regularity. While he lacked an overpowering fastball, he learned how to mix his four-pitch arsenal: a sinking fastball, a curve ball, a slider and a change-up. He made 29 starts, logged 212 innings and posted a solid ERA of 3.35. His record of 9-14 was mostly an indication of poor run support, and not an indictment of the quality of his pitching.

The following year, Osteen emerged as a workhorse. He pitched 237 innings, made 36 starts, lowered his ERA to 3.33 and won 15 games, the latter total especially impressive for a team that won only 62 games and finished last in the league. American League writers took notice, giving Osteen some back-of-the-ballot support in the league’s MVP voting.

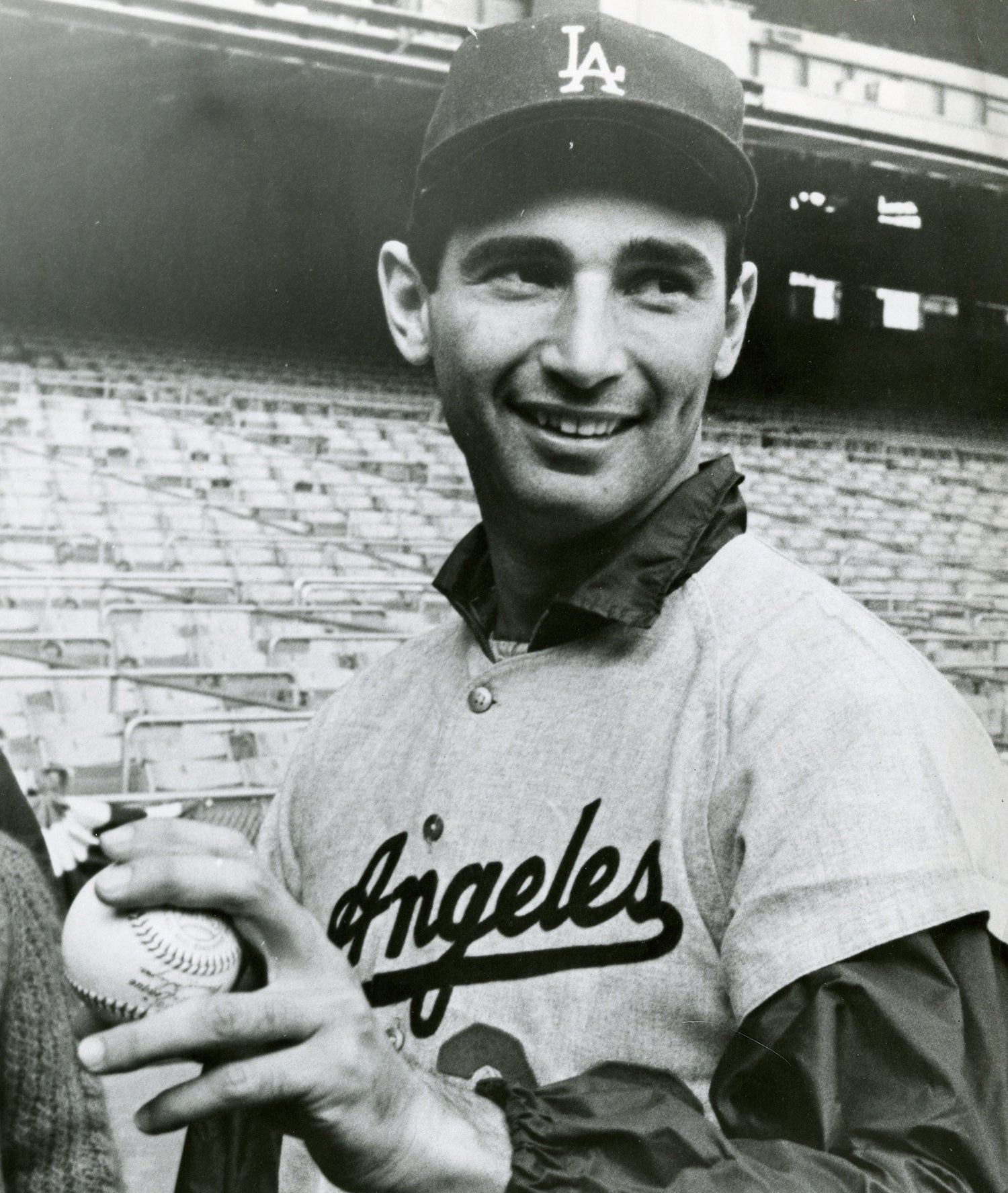

Osteen’s performance made him the ace of the Senators’ staff, but did not cement his future in Washington. With his trade value at a personal high, the Senators decided to cash in; that winter, they traded Osteen, infielder John Kennedy, and $100,000 to the Los Angeles Dodgers for a package of Frank Howard, Ken McMullen and Pete Richert.

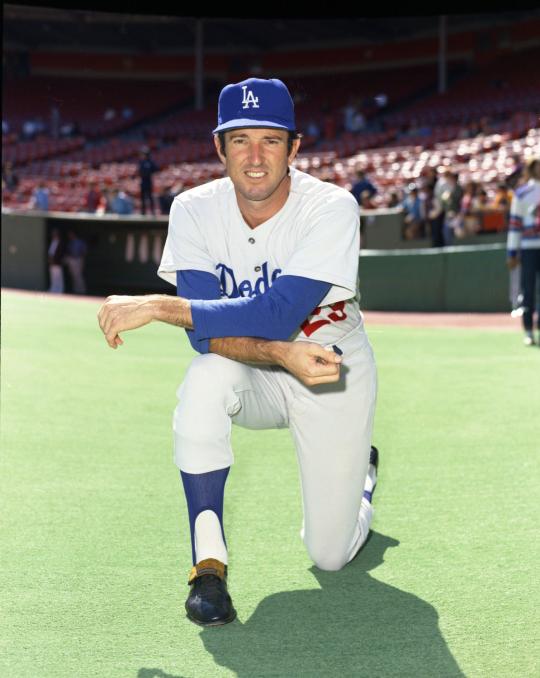

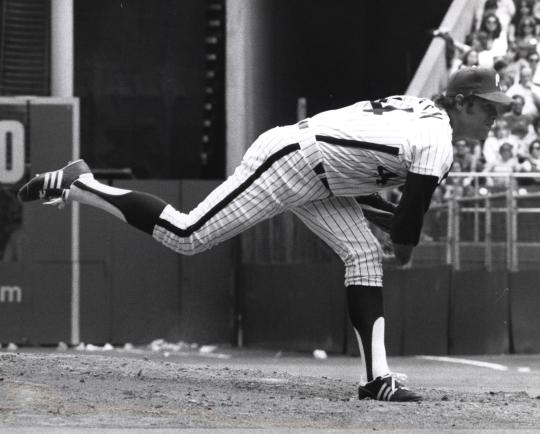

As much as the trade from Cincinnati to Washington had saved Osteen’s career, the latest transaction elevated his status to that of an All-Star. Joining a pennant-contending team in Los Angeles, one that played in the most pitcher-friendly ballpark in the major leagues (Dodger Stadium), Osteen blossomed – even as most of the headlines went the way of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

While Koufax and Drysdale relied on power and more natural pitching talents, Osteen came to depend on finesse and keeping the ball low in the strike zone.

In 1965, Osteen won 15 games, posted an ERA of 2.79 and threw a total of 287 innings. As a team, the Dodgers won the pennant, before moving on to defeat the Minnesota Twins in the World Series.

It was during his first season in Los Angeles that some of his Dodgers teammates pinned him with his nickname, “Gomer,” because of his uncanny resemblance to actor Jim Nabors and his television character, the bumbling Gomer Pyle. While Osteen did not mind the nickname, he also expressed concern that he might become known for the lack of intelligence shown by TV’s Gomer.

“I don’t object to [the name],” Osteen told Bud Furillo of the Sporting News. “But it has created a misconception around the league and with the fans. They associate me with the character Nabors plays and regard me as some kind of idiot. I am nothing like Gomer.”

And then, not wanting to insult Mr. Pyle, Osteen added a postscript to his last remark, saying, “Gomer’s lucky.”

Over the next two seasons, Osteen continued his run of success for the Dodgers. He struggled through a bit of a dip in 1968, when he lost 18 games, but bounced back with his first 20-win season the following summer. He claimed that the Major League Baseball rules change that lowered the mound in 1969 actually helped him, since he relied less on power, and more on precision and control.

Osteen would remain a dependable starter for the Dodgers over the next four seasons. With his easy mechanics, he maintained a high level of durability, averaging 250 innings per year over that span and not spending a single day on the disabled list. He also won 20 games in 1972, marking the second time he had reached the milestone.

Although the veteran left-hander showed no signs of slowing down, and actually made his third All-Star team in 1973, he did turn 34 that summer.

Concerned about his age and looking to upgrade their offensive attack, the Dodgers worked out a deal, sending Osteen to the Houston Astros for slugging outfielder Jimmy Wynn. Osteen would pitch well for the Astros in 1974, but when the team fell out of contention, Osteen realized that a change might be brewing.

“I felt something was in the works,” Osteen informed the Sporting News. “I hadn’t pitched in 17 days, and any time that happens, you know something is up.” Sure enough, the Astros announced a trade, dealing Osteen to the St. Louis Cardinals for a minor league pitching prospect and a player to be named later.

In the midst of a heated division race, the Cardinals gave Osteen only two starts while using him mostly out of the bullpen, a role that had always proved problematic for him. Osteen struggled down the stretch, as the Cardinals lost the Eastern Division race on the final day of the regular season.

In 1975, Osteen reported to Spring Training with the Cardinals but did not pitch well. Just before Opening Day, the Redbirds released him. He received interest from a number of teams, including the defending world champion Oakland A’s, but opted to sign with one of Oakland’s divisional rivals, the Chicago White Sox. That gave him the chance to work under the tutelage of famed pitching coach Johnny Sain.

Unable to regain his earlier form, Osteen struggled, winning only seven games. By his own admission, he lost the feel on his change-up and lacked the pinpoint control that he had previously featured.

The following spring, the White Sox released Osteen, a year to the day after he had been released by St. Louis.

He contemplated signing with another team, as friends reminded him that he was only four wins short of 200 victories, but he decided that the time was right to retire.

Given his intelligence, his ability to dissect pitching mechanics, and his general understanding of how to set up hitters, Osteen made a natural transition to coaching. At first, he worked in the minor league system of the Philadelphia Phillies, before receiving a surprising offer to serve as pitching coach on the Cardinals’ major league staff. He spent four seasons with the Cardinals, before moving back to the Phillies’ organization in 1982, this time as their big league pitching coach.

It didn’t take long for Osteen to gain favor with his new Phillies pitchers. As Dick Ruthven told sportswriter Mark Whicker of the Philadelphia Daily News, “Claude Osteen is the best addition this club has made.” One year later, Osteen’s work paid off even more handsomely in the form of a National League pennant.

In 1989, Osteen went to work in the minor league system of the Dodgers, the team with which he was most associated as a pitcher. He later joined the Texas Rangers’ major league staff, before returning to the Dodgers as their pitching coach in 1999 and 2000. From there he moved on to the Arizona Diamondbacks as a scout and consultant before retiring from the game in 2009.

As a coach, Osteen enjoyed nearly as much success as he did as a pitcher. He may have looked like Andy Griffith’s Gomer, a beloved character not known for his smarts or common sense. But this version of Gomer had plenty of intelligence and wisdom when it came to the fine art of pitching a baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame