- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1959 Topps Moe Drabowsky

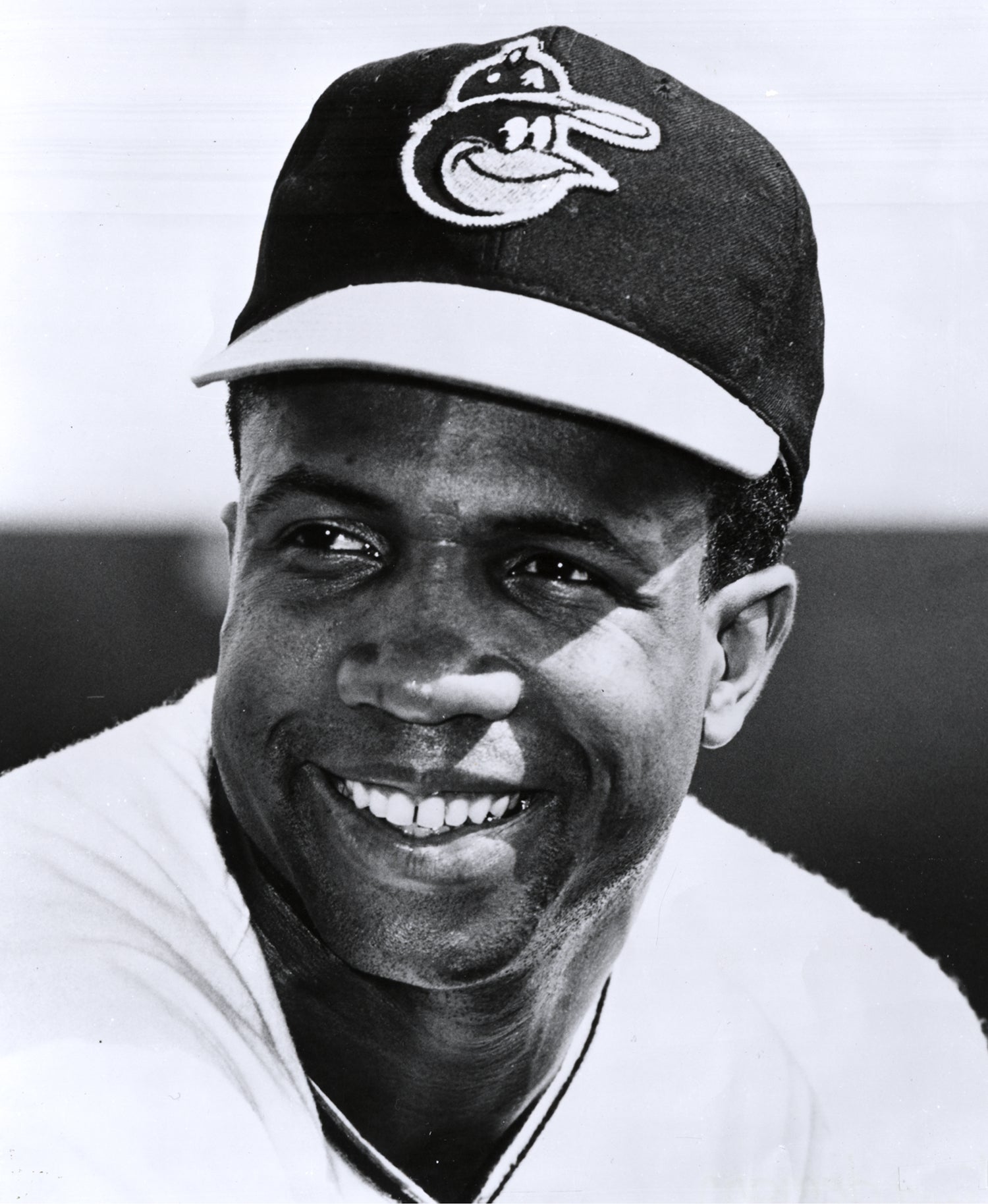

#CardCorner: 1959 Topps Moe Drabowsky

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

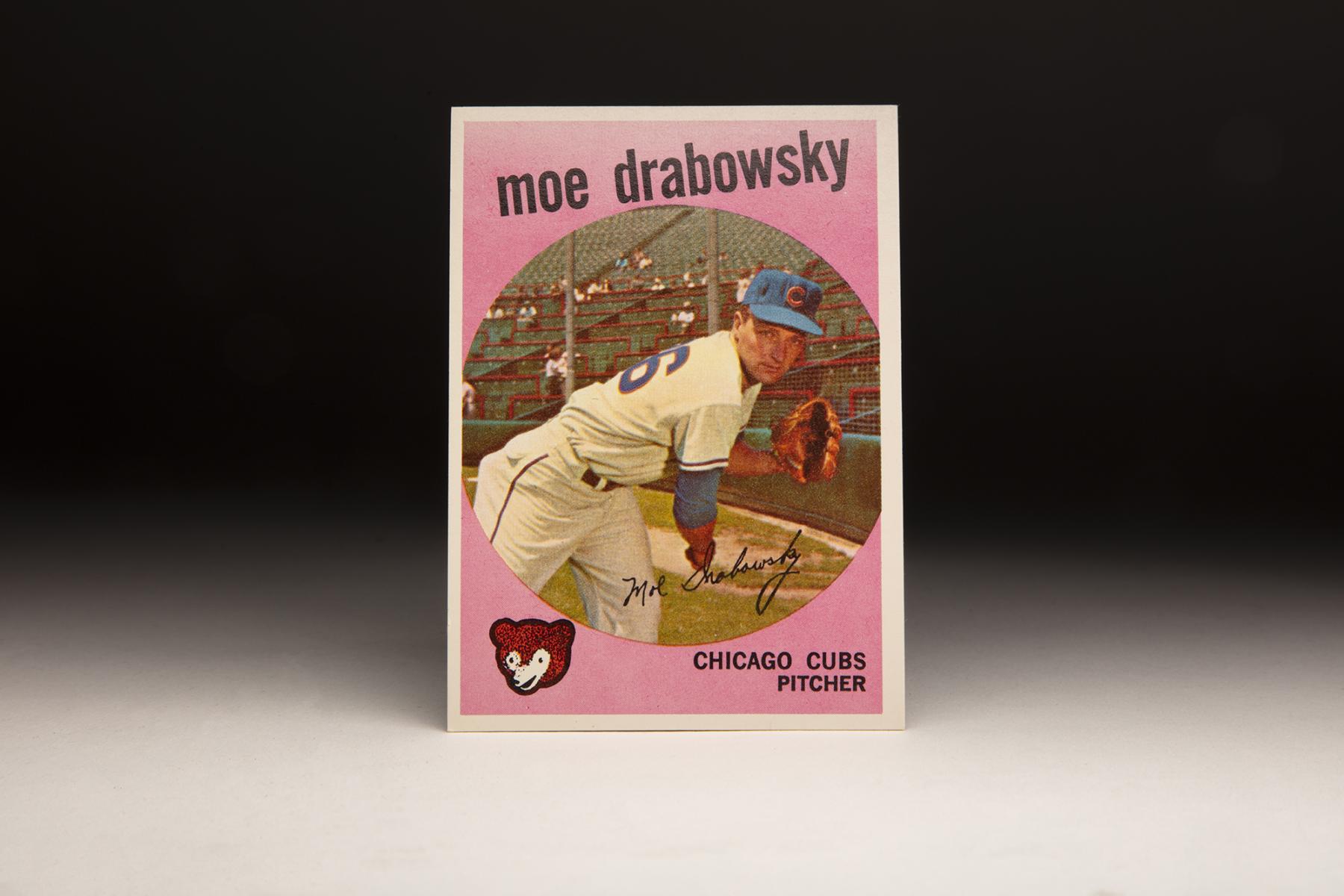

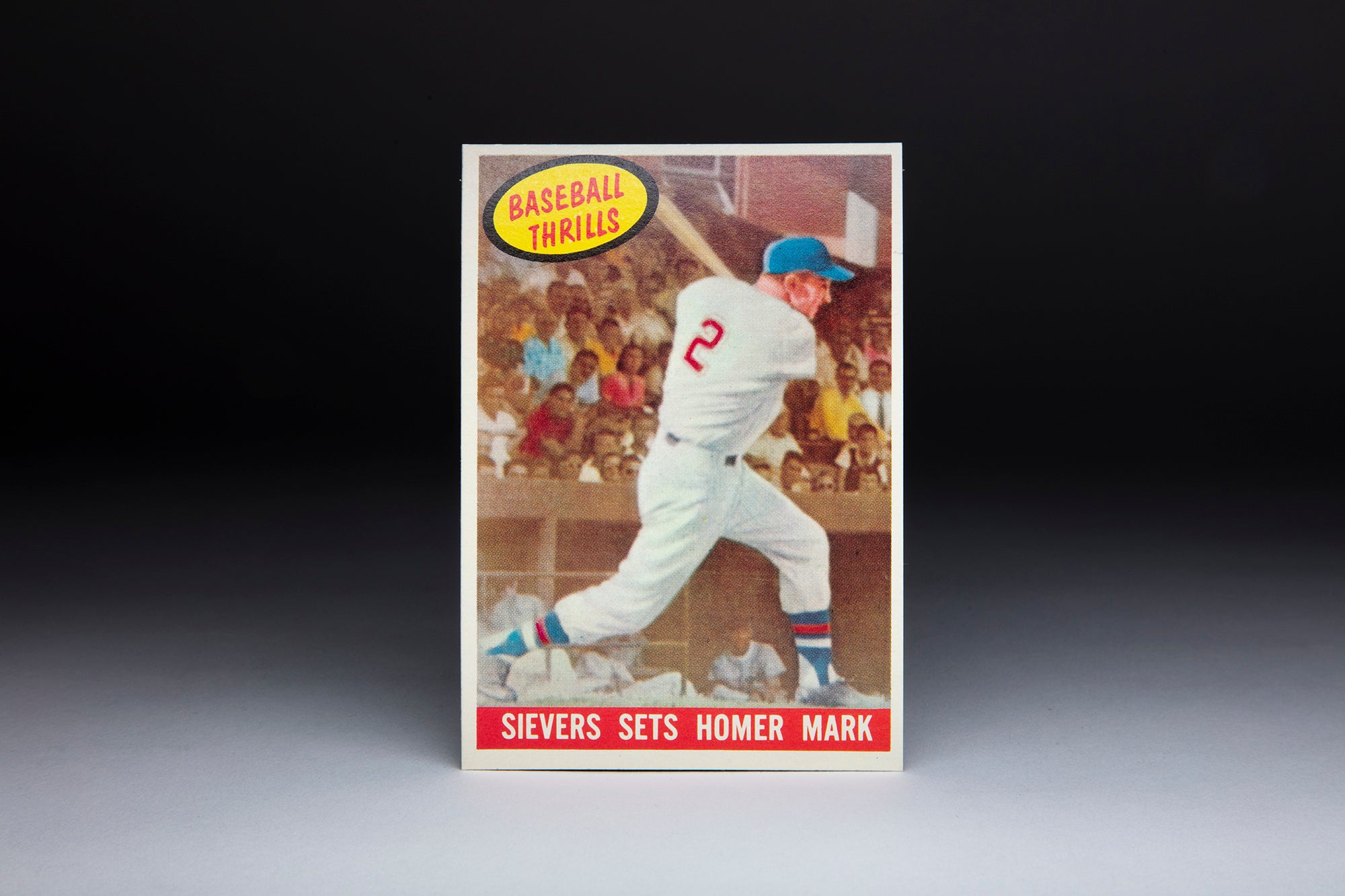

For one of the few times in his life, Moe Drabowsky appears to be playing it straight on his 1959 Topps card. No laughing. No hijinks. No pranks or practical jokes. No giving the Commissioner of Baseball a hot foot. No, on this card, Drabowsky is all business.

In posing for this shot at Wrigley Field, the veteran right-hander appears to be doing his best simulation of his pitching motion. Pretending to throw on the sidelines before a sparse pregame crowd in Chicago, Drabowsky gives us a pretty good rendering of a pitcher in motion. Drabowsky is also sporting a very serious look on his face, almost as if he were pitching in an actual game, and not on the sidelines for the Topps cameraman.

Drabowsky’s 1959 card is also distinctive because of the pinkish frame used to surround the circular photograph. Only a handful of ’59 cards featured the pink frame. In fact, in the entire history of Topps I can only recall one other set – the 1975 set with multi-colored borders – that used the color of pink in its design. The ’75 cards had everything: Purple, lavender, bright green, yellow, orange and red.

No color, no matter how bright, could fully capture the nature of Drabowsky of the game’s most colorful characters. Drabowsky was a serviceable pitcher throughout the late 1950s and much of the 1960s, but he is best remembered for his extraordinary talents as a practical joker. As a matter of fact, he might have been the greatest prankster in the history of the game. And it was only fitting that he went by the nickname of Moe, a nickname that conjures up images of The Three Stooges, and their beloved leader, Moe Howard.

Let’s consider just a few of the stunts that Drabowsky pulled off during his long career:

- Drabowsky regularly ordered Chinese food from the bullpen. While he usually called local Chinese restaurants, he once decided to place a long distance call from Anaheim Stadium to a restaurant in Hong Kong. (Drabowsky’s habit reminded me of an episode of Seinfeld, when Elaine attempts to place a takeout order of Chinese food, only to be told that her apartment is out of delivery range. Due to the restriction, Elaine instructed the restaurant to deliver the food to a cramped janitor’s closet in a nearby building. Drabowsky would have appreciated that episode.)

- In addition to the bullpen phone calls, Drabowsky relied on a few other pet tricks. One involved the placement of goldfish into the opposing team’s water cooler. Another involved the addition of sneezing powder to the visiting team’s clubhouse air conditioning system.

- After the 1968 season, Drabowsky departed the Baltimore Orioles, who had left him unprotected in the expansion draft. Now a member of the Kansas City Royals, Drabowsky exacted some revenge on the Orioles in the fall of ‘69, when he sent the American League champions a six-foot-long boa constrictor during the World Series. Coincidentally or not, the Orioles went on to lose the Series in five games to the upstart New York Mets.

- Drabowsky was a master at pulling off the hot foot. He would crawl underneath an unsuspecting victim, light a match, and then apply the match to his victim’s shoe, which resulted in a sharp burning sensation, followed soon after by a loud yell. Not only did Drabowsky target teammates and opposing players; he once pranked the game’s ranking leader. It was during the 1970 World Series, by which time Drabowsky had rejoined the Orioles. Laying out a trail of lighter fluid from the trainer’s room to the clubhouse, Drabowsky managed to set the foot of Commissioner Bowie Kuhn on fire. By using the trail of lighter fluid, Drabowsky made it difficult for Kuhn to uncover the identity of the culprit.

- Drabowsky’s most famous stunt did not involve hotfoots, snakes, sneezing powder or Chinese food. It was during a May 1966 game between the Orioles and the Kansas City A’s. With A’s pitcher “Jumbo” Jim Nash mowing down Drabowsky’s Orioles, the mischievous right-hander placed a call from the Baltimore bullpen to the Kansas City bullpen. Doing his best imitation of A’s manager Alvin Dark, Drabowsky told Kansas City bullpen coach Bobby Hofman to instruct reliever Lew Krausse to begin warming up immediately. “You should’ve seen them scramble, trying to get Lew Krausse warmed up in a hurry,” Drabowsky told the Associated Press. “It really was funny.”

Unnerved by the sight of Krausse warming up and wondering why Dark was showing such little confidence in him, Nash became upset. Drabowsky then placed a second call, telling Krausse to sit down. A few minutes later, he called again, telling Krausse to start warming up. By now the members of the A’s bullpen realized that it was Drabowsky calling – and not Dark. The A’s soon hung up the phone.

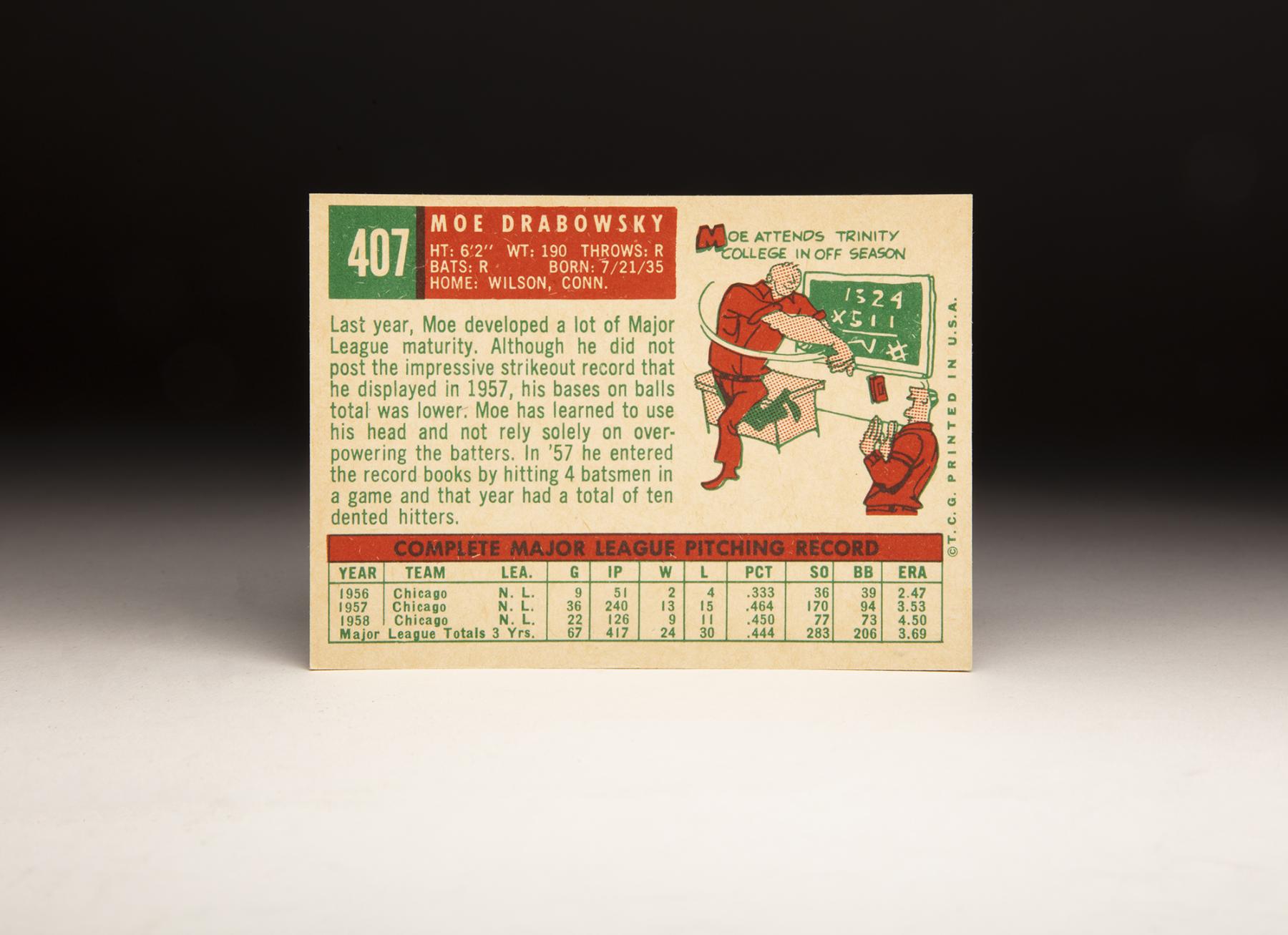

Such fun often overshadowed Drabowsky’s pitching abilities, which were certainly more than respectable. Born in Poland, Myron “Moe” Drabowsky and his family moved to the U.S. when he was only three. In time, he became a highly sought after commodity by a number of big league teams. The Chicago Cubs won the bidding and signed him out of Trinity College in 1956, giving him a large bonus that Drabowsky said totaled $75,000. That made him one of the earliest of the so-called “bonus babies.”

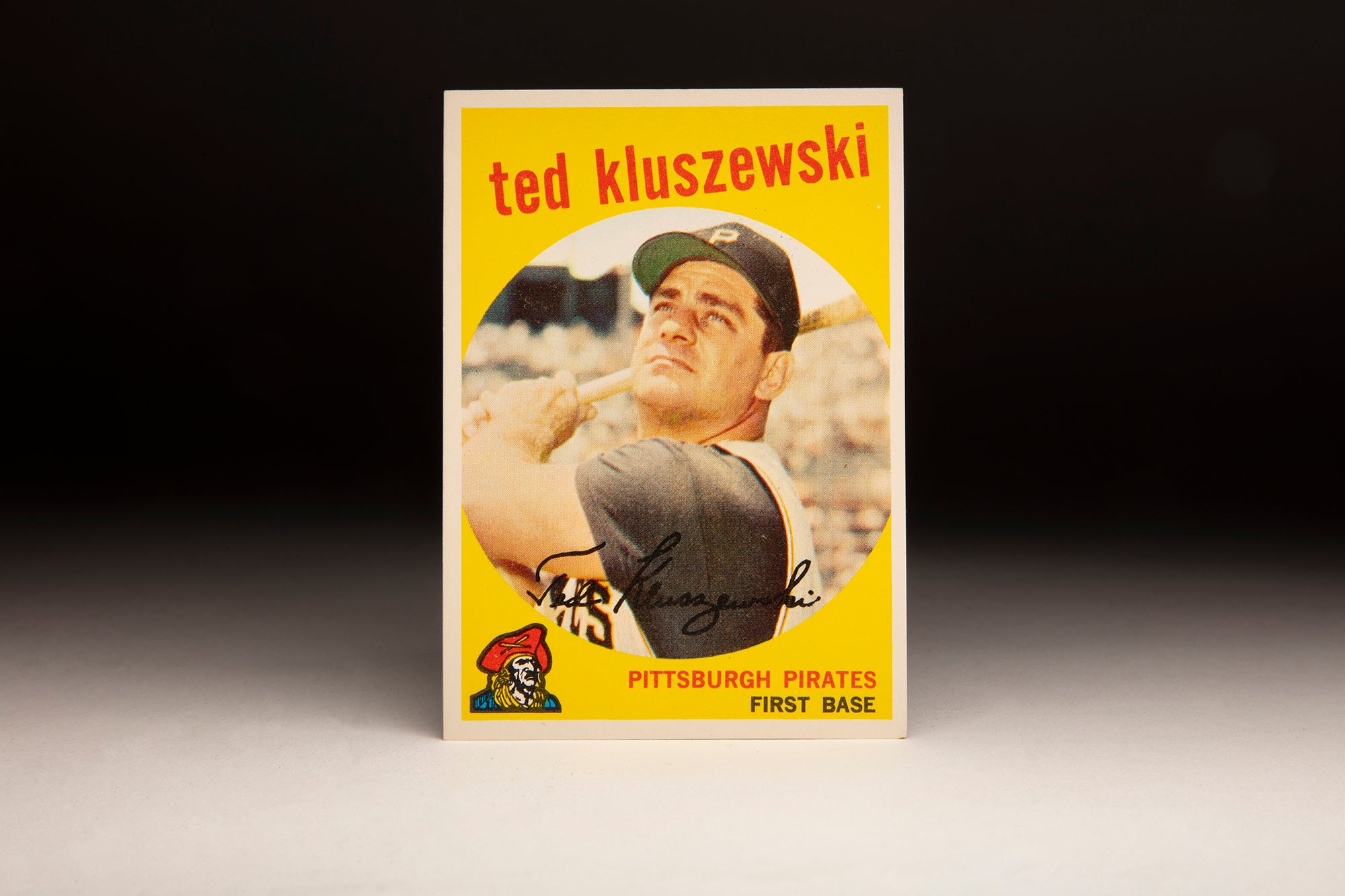

According to the rules of the day, a player receiving a bonus that exceeded $4,000 had to be immediately placed on the major league roster. So after signing with the Cubs on July 22, Drabowsky completely bypassed the minor leagues and reported immediately to the big league club. Drabowsky pitched well in his debut, a scoreless inning in relief. But nerves overcame him in his second appearance. “The next night in Cincinnati, I really had the jitters,” he told the Chicago American. “The first man I faced was Ted Kluszewski. I was so worried I threw him four straight balls.”

From there, Drabowsky settled down somewhat. He pitched sparingly that summer, receiving seven starts after the two relief appearances, but he performed respectably. He recorded an ERA of 2.47, though he did struggle mightily with his control. Still only 20 years old, he walked 39 batters in 51 innings.

While Drabowsky would eventually become known as a jokester, he initially came across as a serious individual to his teammates. He could often be seen carrying a copy of the Wall Street Journal, a publication that he read with regularity.

Some of his teammates kept their distance from him because they felt that he was too serious in his demeanor. That, of course, would eventually change.

In 1957, Drabowsky became the workhorse of the Cubs’ staff. Employing a repertoire of a live fastball, a curve ball, and a changeup, he worked 240 innings, completed 12 games, won 13 and posted an ERA of 3.53.

That winter, Drabowsky spent much of his time serving in the Army Reserves. He then came down with a throat ailment, which resulted in a significant loss of weight and a late arrival to Spring Training.

Not surprisingly, his pitching suffered in 1958. Making only 20 starts, he saw his ERA rise to 4.51 and his win/loss record fall to 9-and-11. To make matters worse, he felt something in his elbow snap during a game in July. He missed a start and underwent treatment, which helped initially, but he began to favor the elbow, which placed unwanted strain on his shoulder.

For the next few seasons, the condition of Drabowsky’s arm compromised his pitching. He struggled badly in 1959 and ’60, with his ERA rising to 6.44 the latter season. Drabowsky pitched so poorly in 1960 that he spent part of the season trying to work out his problems in Triple-A ball. Perhaps realizing that his baseball career might not last as long as he wanted, Drabowsky began to plan for the future. After the 1960 season, he took a training course to become a licensed stock and bond broker.

The following spring would bring another change to Drabowsky’s routine.

Late in Spring Training, the Cubs gave up on the ailing right-hander, sending him to the Milwaukee Braves for infielders Andre Rogers and Daryl Robertson.

The trade resulted in a bit of a detour to Drabowsky’s career. Starting the season in Milwaukee, Drabowsky did not fare well, striking out only five batters against 18 walks in 25 innings.

In June, the Braves farmed him out to their Triple-A affiliate at Louisville, where he remained for the balance of the 1961 season.

After the season, Milwaukee dropped Drabowsky from its 40-man roster, allowing the Cincinnati Reds to claim him in the Rule 5 draft. But his time in Cincinnati turned out to be short-lived, too.

Splitting his role between the bullpen and the rotation, he mostly struggled with the Reds. In August, Cincinnati decided to move on, selling him to the Kansas City Athletics.

Over the balance of the 1962 season, Drabowsky fared no better for the A’s than he had for the Reds and Braves. The 1963 season would bring better results, however. Used somewhat regularly as a starter, Drabowsky lowered his ERA to 3.05 and struck out 109 batters.

That would represent the high point of Drabowsky’s time in Kansas City. He pitched poorly over the next two seasons, resulting in another change of location.

During the winter of 1965, the A’s sold his contract to the St. Louis Cardinals.

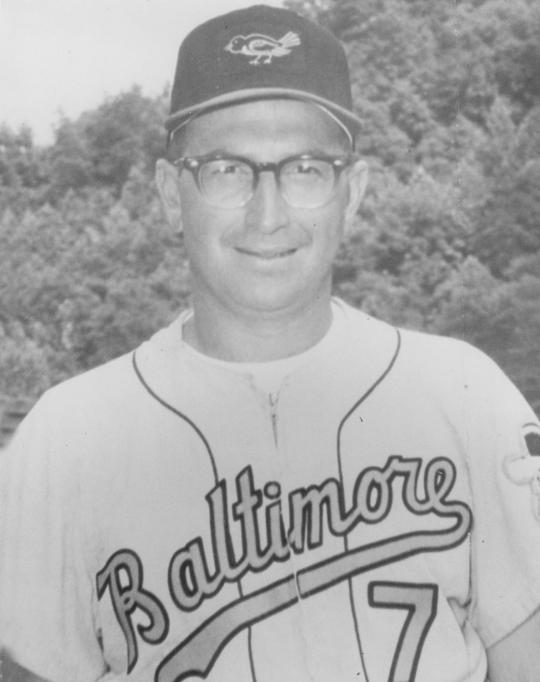

Roughly a month later, the Orioles selected him in the Rule 5 draft for all of $25,000. It would turn out to be a coup for the Orioles.

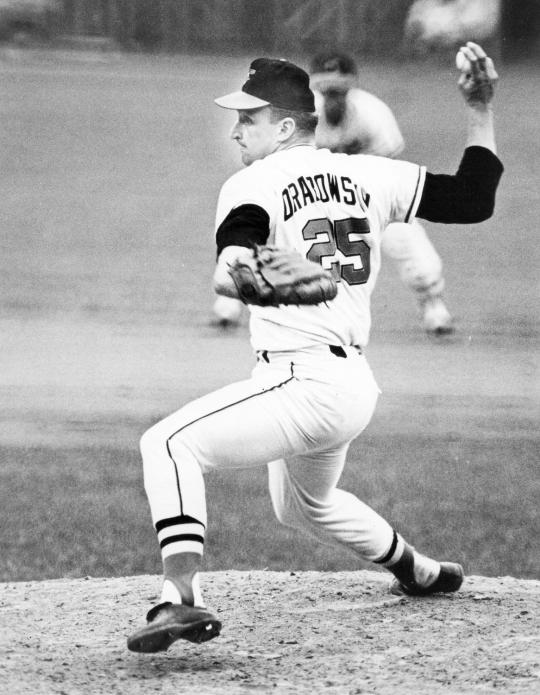

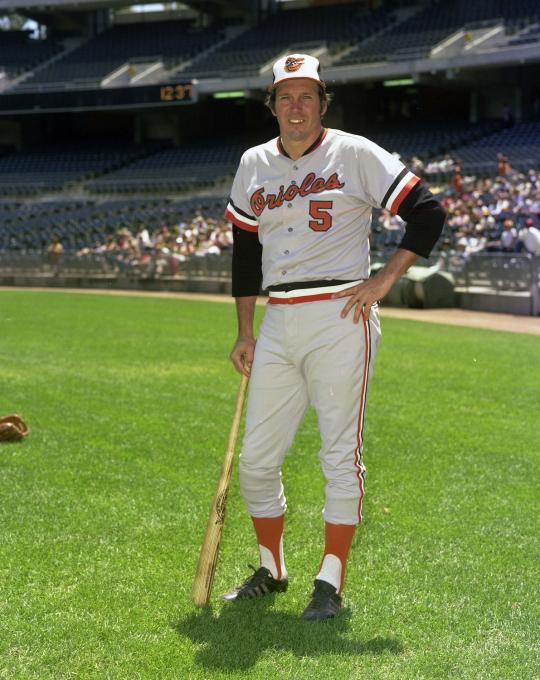

In 1966, Orioles manager Hank Bauer made Drabowsky a fulltime reliever. Hurling 96 innings, Drabowsky struck out 98 batters, won all six of his decisions, and posted an ERA of 2.81. He also saved six games as part of Bauer’s strong bullpen by committee.

As a team, the Orioles won the American League pennant, earning a berth in the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Drabowsky’s first World Series appearance allowed him to make national headlines. Relieving Dave McNally early in Game 1, Drabowsky came on to pitch six and two-thirds innings of one-hit ball and set a World Series record for relievers by striking out 11 batters. At one point, he fanned six consecutive Dodgers. Buttressed by Drabowsky’s Herculean relief effort, the Orioles won Game 1, setting the tone for a surprising four-game sweep of the Dodgers.

After the game, the media gathered around Drabowsky and two of Baltimore’s stars, Brooks and Frank Robinson.

“Just what is a guy like me doing in fast company like this?” Drabowsky told the Chicago Tribune.

“I couldn’t wish for a situation to arise that would call for me to be a hero. I did hope, though, that I’d be able to see a little action in the Series.”

After helping the Orioles win the Series in 1966, Drabowsky actually pitched better out of the bullpen in 1967 than he had in ’66. He put up a career-best 1.60 ERA over 95 innings, while saving 12 games.

As a team, though, the Orioles suffered a letdown and finished a dismal sixth in the American League.

Drabowsky continued his excellent work in 1968, with an ERA of 1.91 ERA. Based on his strong performance over the last three seasons, Drabowsky would have seemed like a lock to return to the Orioles in 1969. But the offseason that followed 1968 was different; two new expansion clubs in the American League had to be stocked with players. Unable to protect all of their good players, the deep and talented O’s felt they had no choice but to leave the 32-year-old Drabowsky exposed to the expansion draft. The Royals took advantage, selecting the stalwart reliever.

Over the next season and a half, Drabowsky excelled out of the Royals’ bullpen, remaining durable and efficient. The Royals, however, were a new team looking to build with young players, giving them less incentive to keep a 34-year-old relief pitcher on the active roster.

In the middle of the 1970 season, the Royals traded Drabowsky, sending him back to the Orioles in a deal for a young infielder named Bobby Floyd.

Drabowsky pitched credibly over the balance of the season, as the Orioles ran away with the American League pennant. After being bypassed in the ALCS, Drabowsky made two appearances in the World Series – a five-game demolition of the Reds. And with that, Drabowsky had earned his second Series ring.

Once again becoming expendable, Drabowsky departed the Orioles in a wintertime trade, this one sending him to St. Louis for infielder Jerry DaVanon.

Pitching well over the next season and a half, Drabowsky then finished his career with a strong six-game stint for the Chicago White Sox in the latter stages of 1972. While Drabowsky’s numbers in Chicago looked good, he felt like he had lost his ability to pitch when he delivered a flat, lifeless pitch to Boston’s Tommy Harper.

“I watched that ball go to the plate and I said [to myself], ‘When in the world is that ball gonna get to the plate?’ I said, ‘Hey, my career is over,’ ” Drabowsky recalled in an interview with Sports Collectors Digest.

With his pitching career coming to an end in 1972, Drabowsky left baseball completely. He had thought about coaching, but the relatively low salaries at the time convinced him to pursue another line of work.

At first, he went to work for a company that produced envelopes and then joined a communications firm based in Canada.

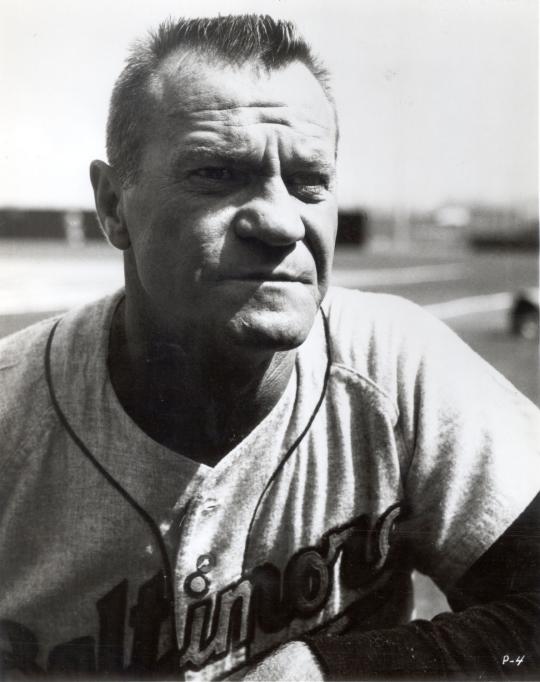

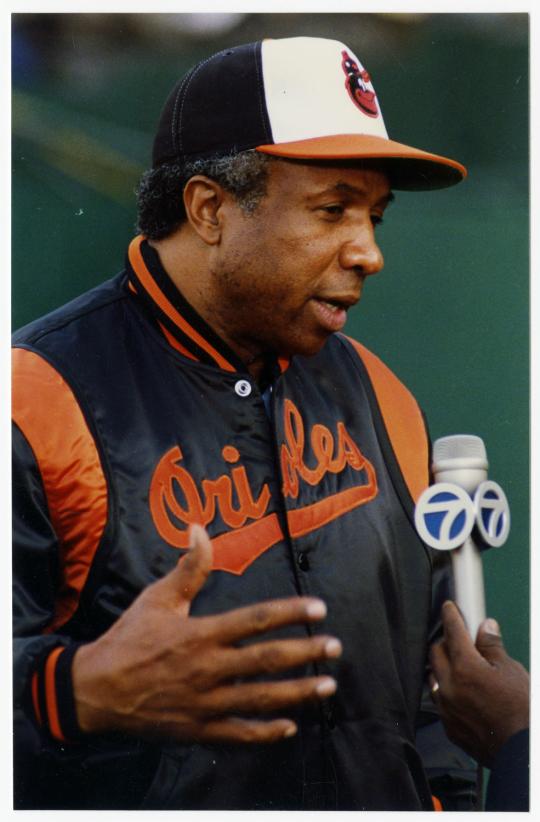

In the late 1980s, Drabowsky returned to the game. He joined the staff of the Chicago White Sox, before eventually moving on to the crosstown Cubs as a minor league instructor. From there, he rejoined the Orioles’ organization.

As a pitching coach, Drabowsky relied heavily on the study of film and videotape, something he had done during his own playing days in the 1960s.

Approaching his job as a pitching coach with enthusiasm, Drabowsky became very popular with many of his young pitchers.

After his retirement from coaching, Drabowsky remained active by attending Orioles fantasy camps. There he continued his habit of pulling off practical jokes, which often included the use of live snakes. One day, the local police, who happened to know Drabowsky, arrested him on the charge of “cruelty to animals.” When Drabowsky arrived at the police station, the police informed him that the “arrest” was nothing more than a practical joke.

As Drabowsky continued his coaching career with the Orioles in 2000, he received an undesirable diagnosis: Advanced stage multiple myeloma. Doctors gave him only six months to live, but Drabowsky’s determination, along with a willingness to try stem cell transplants, extended his life by six years. He finally succumbed to the disease in 2006, at the age of 70.

Drabowsky’s passion for living matched his passion for playing jokes and pranks on friends and opponents. When it came to living a full and vibrant life, few could match the efforts of a one-of-a-kind pitcher named Moe.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame