- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1984 Topps Richie Hebner

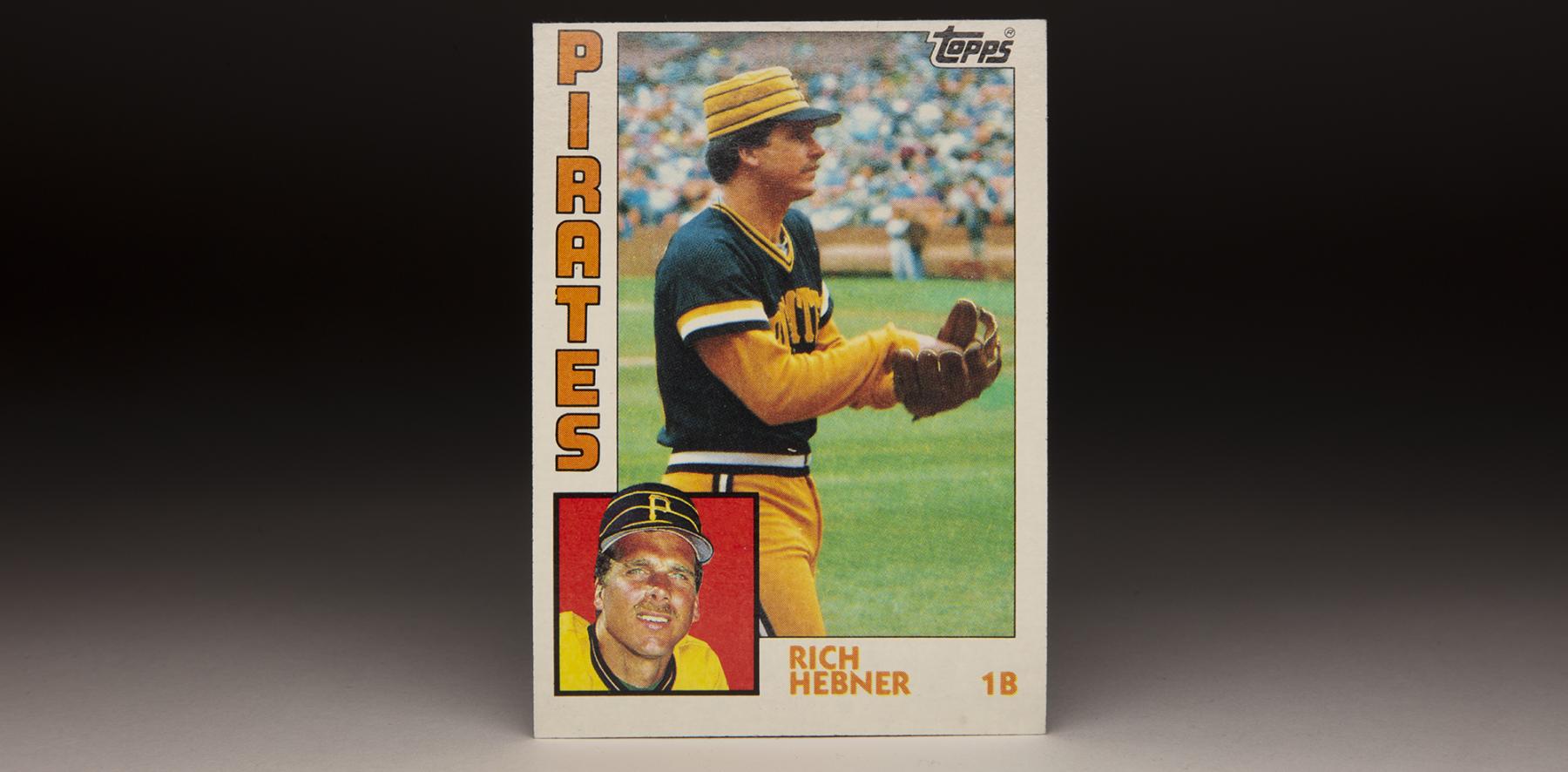

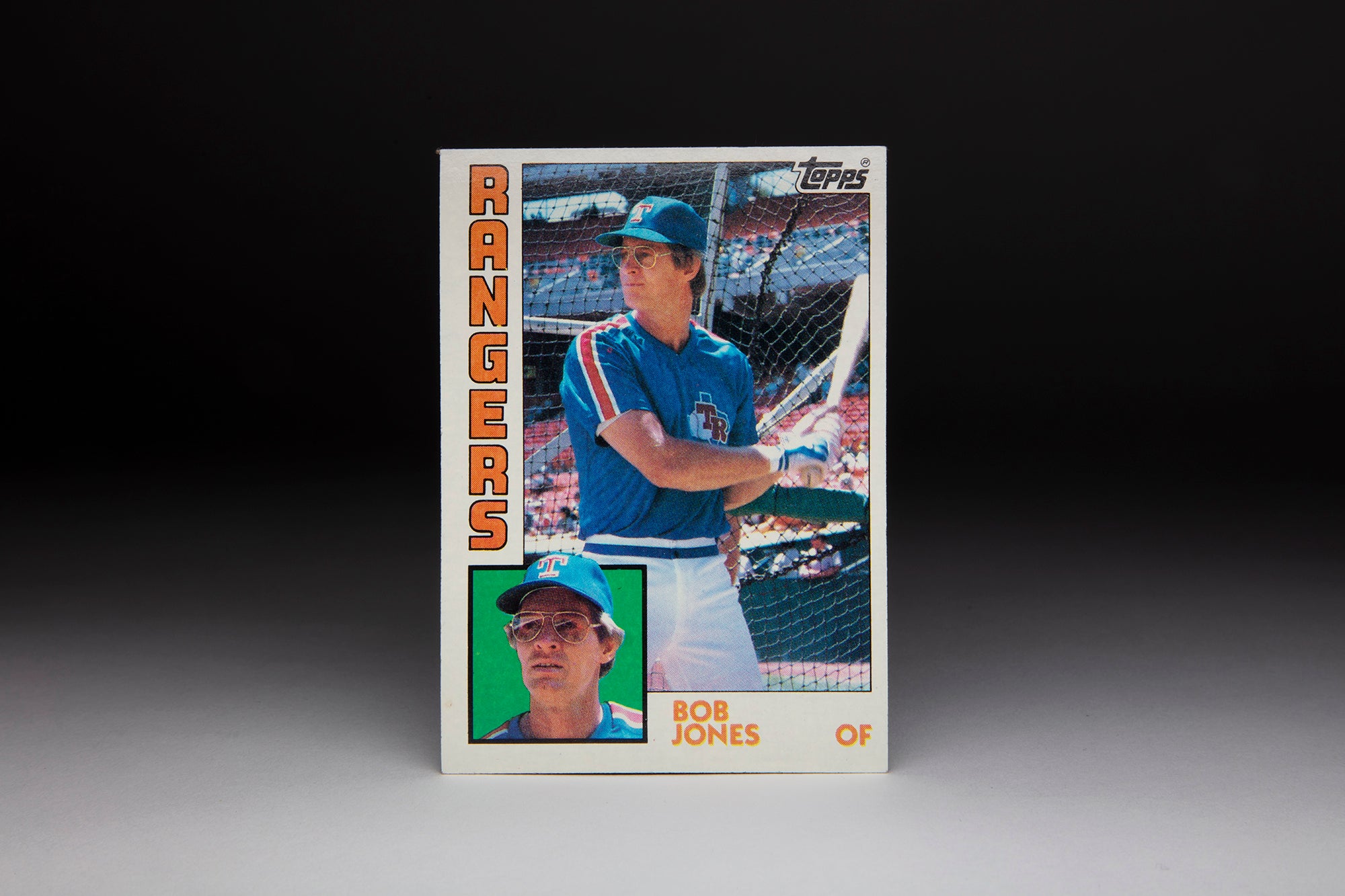

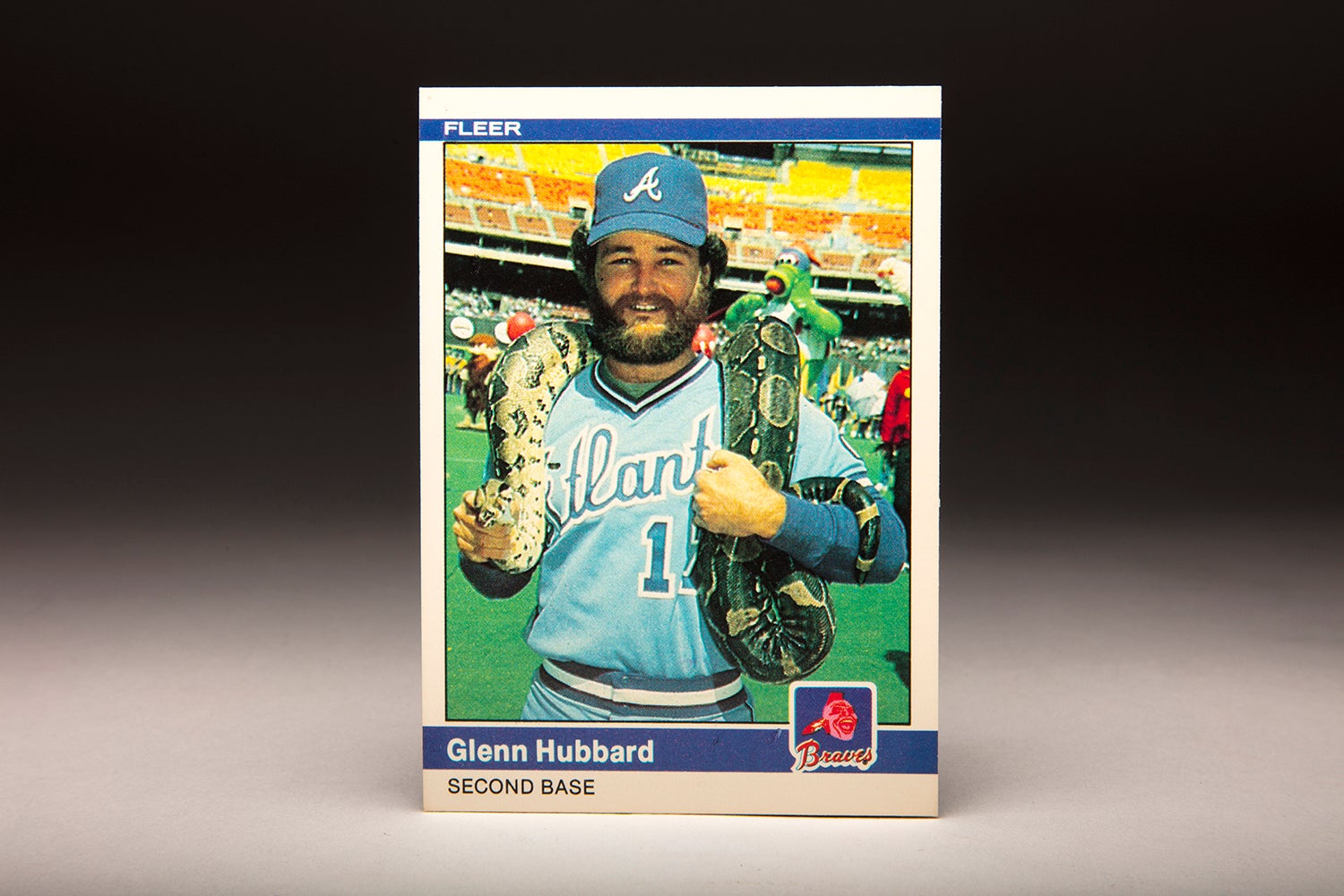

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Richie Hebner

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

If you collected baseball cards in both the 1970s and 80s, you likely experienced two different incarnations of Richie Hebner.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

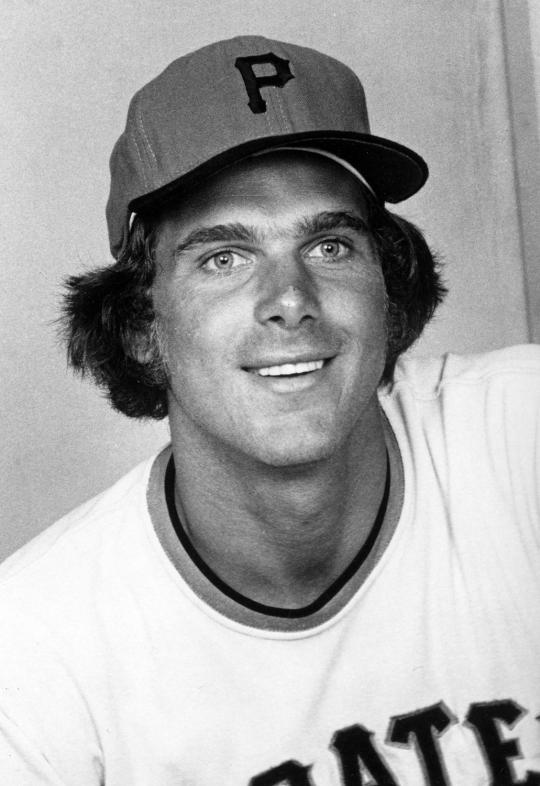

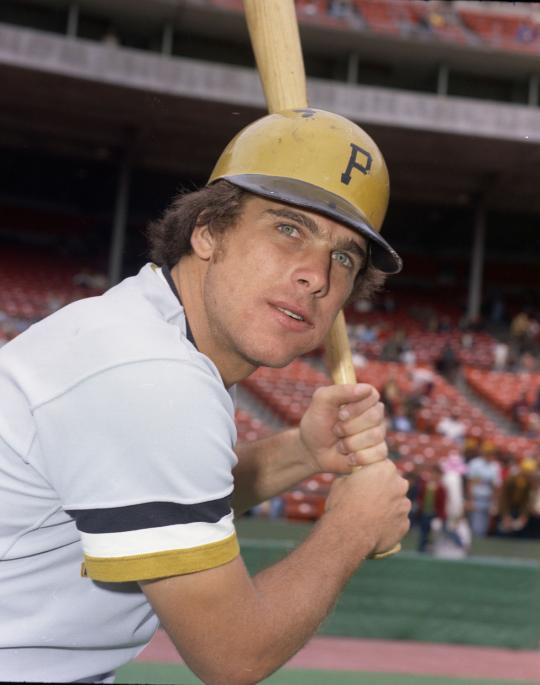

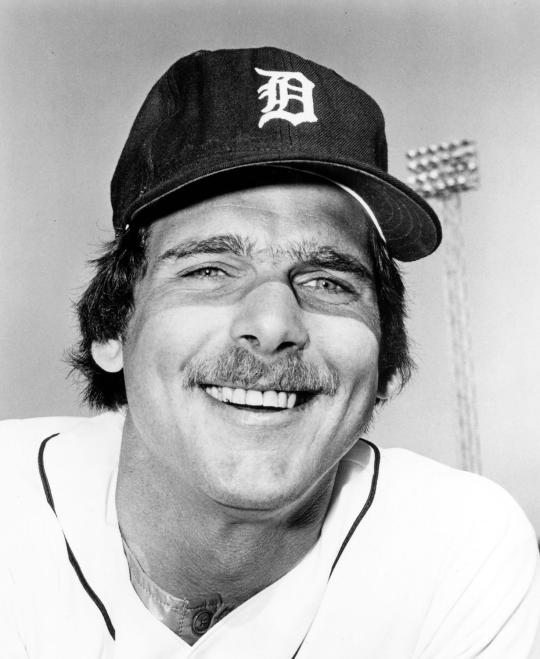

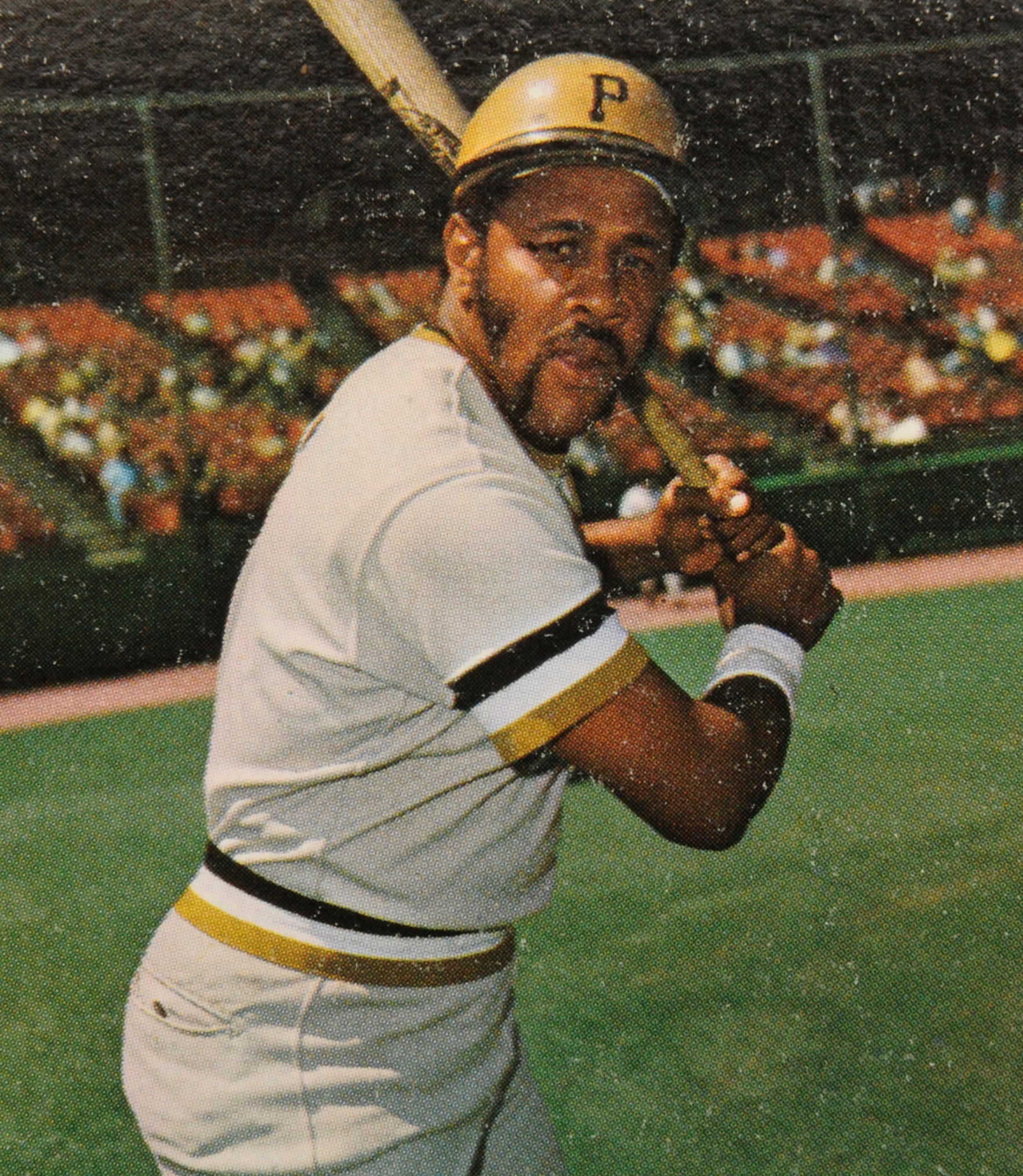

The first one was a clean-cut, youthful Hebner sporting the Pittsburgh Pirates’ more conservative white and gray uniforms. The second one was a more mature Hebner, with mustache in full bloom, his hair a bit longer, and his body draped in the bold black-and-gold threads that made the Pirates the most distinctive looking team in the early 1980s.

Hebner’s 1984 Topps card gives us an ideal example of the latter incarnation. Taken on the sidelines before a game, the photo showcases the Pirates’ black jersey, the gold undershirt, the matching gold pants, and that wonderful pillbox cap, which much of the National League debuted in 1976 but which the Pirates maintained for more than a decade.

Seemingly oblivious to the Topps photographer on the sidelines, Hebner appears to be taking in a pregame catch with some unseen teammate. He is rather gingerly reaching into his glove, as if he is about to remove a fragile egg, rather than a hardened, 108-stitch baseball. I imagine that this was all part of a pregame routine that Hebner had established many years earlier.

Photographers would have had plenty of opportunity to take baseball card shots of Hebner. He was a player known for arriving at the ballpark early, often before the vast majority of his teammates. A baseball lifer through and through, Hebner loved spending hours at the ballpark, both before and after the game.

Though Hebner would become associated with baseball, he at one time seemed destined to play another professional sport. Growing up in Brighton, Mass., Hebner became a highly touted hockey player, so skilled and talented that he drew the interest of the NHL’s Boston Bruins. In some ways, hockey was Hebner’s first love, but he also excelled at baseball, becoming a hard-hitting shortstop in both Little League and high school. In 1966, the Pirates presented Hebner with a difficult decision by making him their first-round choice (15th overall) in the MLB Draft.

As much as Hebner loved hockey, he realized that the money he could make in baseball was potentially far greater than the salaries of hockey players at the time. The Bruins offered him a bonus of $10,000, far less than the $40,000 being offered by the Pirates. So Hebner opted to take the Pirates’ offer, accepting an assignment to Salem, Va., of the Appalachian League.

Like many athletes of the era, Hebner faced the real possibility of being drafted to fight in the ongoing Vietnam War. He decided to enter the Marine Corps Reserves, which involved a commitment of weekend duty once a month, along with a two-week stint during the summer, but would also keep him out a fulltime assignment to the conflict in Vietnam.

Hebner reported to Salem and wowed the Pirates with his smooth left-handed swing, hitting .359 with a .652 slugging percentage. Near the end of August, Hebner left Salem to begin six weeks of military training at Parris Island, S.C. There he improved his physical conditioning, adding several pounds of muscle and bulking up to 195 pounds.

In 1967, the Pirates bumped Hebner up to Raleigh of the Carolina League. He didn’t hit with much power (two home runs in 78 games) but compiled a .336 batting average and an OPS of .867. His season ended two months early, however, because of a fit of temper. After striking out in a game in late June, he threw a punch at the roof of the dugout, resulting in a broken right hand. As a result, Hebner missed the balance of the season.

While the Pirates weren’t happy with his loss of temper, they still decided to promote him to Triple-A Columbus to start the 1968 season. Playing at a higher level, Hebner did not hit as well as he had in rookie and Class A ball, but showed enough to earn a late-season call up to Pittsburgh. On Sept. 23, Hebner made his major league debut for the Pirates. He appeared in two late-season games, going 0-for-1 at the plate.

Given the loss of Maury Wills in the expansion draft, the Pirates had a need for a new third baseman in 1969. The Pirates made Hebner their Opening Day starter at the position and batted him second, just ahead of Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. For most of the season, Hebner platooned with veteran infielder and converted shortstop Jose Pagan (the subject of our first Card Corner).

Compiling most of his at-bats against right-handed pitching, Hebner batted .301, drew as many walks as strikeouts (53) and compiled a .380 on-base percentage. He showed only a modicum of power (eight home runs), but that aspect of his game would develop soon enough.

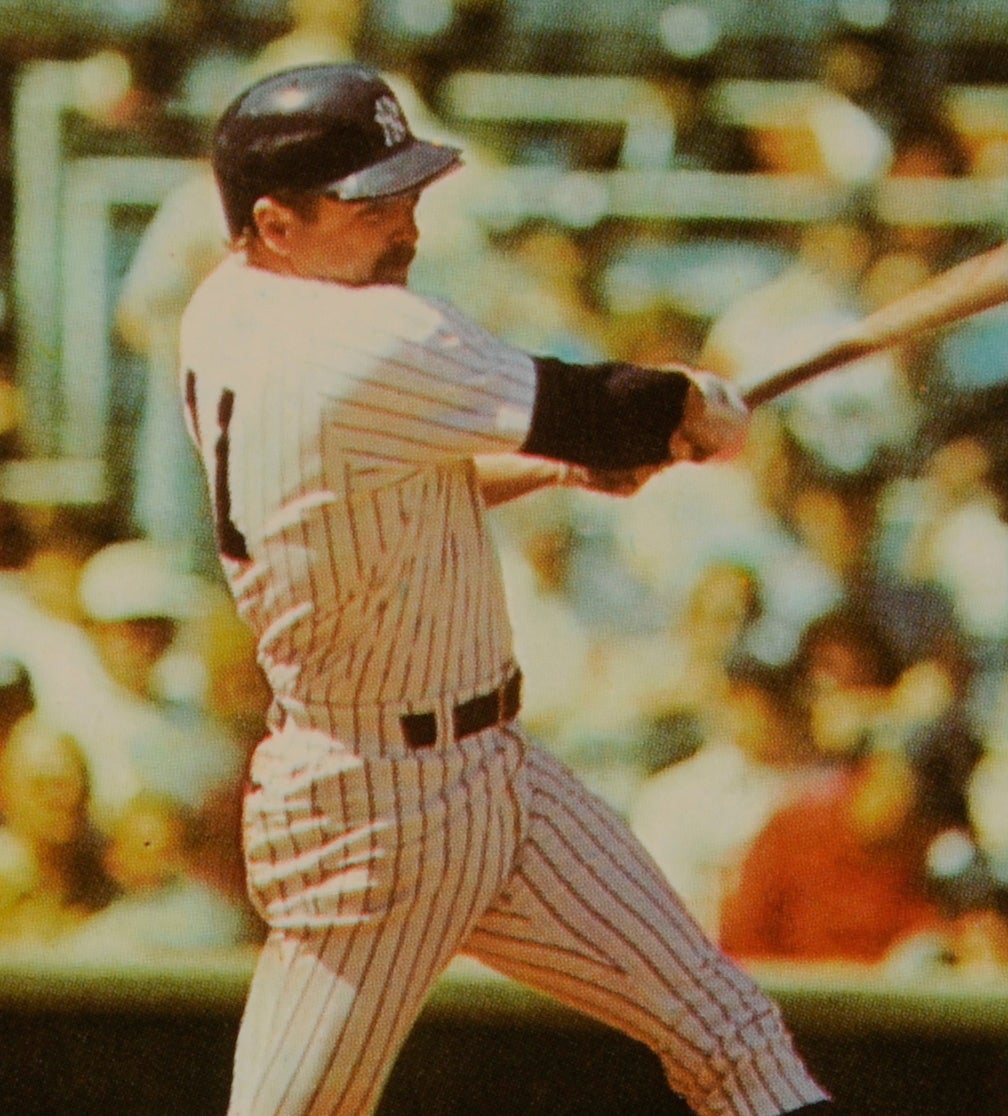

Hebner quickly became one of the more distinct looking hitters in the major leagues. As he stepped into the batter’s box, he tugged at his jersey several times, as if it didn’t fit him properly. He then batted out of a deep crouch, which indicated his preference for low pitches. When he swung and missed, he sometimes flipped the bat into the air as a mild show of frustration.

After another solid season in 1970, Hebner hit 17 home runs in 1971, as he continued to form an effective platoon with Pagan at third base. With an OPS of .813, Hebner gave the Pirates another dangerous left-handed bat behind Willie Stargell and Al Oliver. After helping the Pirates win the National League East, he enjoyed a productive NLCS against San Francisco, hitting. 294 with two home runs. Then came the World Series, where Hebner hit his third home run of the postseason, as the Pirates pulled off a monumental seven-game upset of the Baltimore Orioles.

As the Pirates made headlines during their world championship run, so too did Hebner for his unusual wintertime occupation. By 1971, many writers began to refer to his offseason profession of gravedigger. He had been given the unconventional job by his father, the superintendent of several cemeteries in Massachusetts. The job paid Hebner $35 for each grave. Hebner told writers that he could dig a grave rapidly, usually within about two hours.

On occasion, Hebner’s father questioned the depth of his graves. “That’s a little too shallow, isn’t it?” Mr. Hebner said, according to a Los Angeles Herald Examiner article written by Jim Perry. “No,” said Richie in response. “I’ve yet to see one of them come up.”

The Pirates, like most of the baseball world, viewed Hebner’s wintertime profession with amusement. They took even more joy in the way that he played on the field; in 1972, Hebner put even better offensive numbers than he had in ’71, lifting his average to .300 and his OPS to .886.

In 1973, Hebner upgraded his power. Satisfied in using the entire field over the first few years he was in the big leagues, Hebner made a conscious decision to pull the ball more often in ’73. That change resulted in a significant boost in power. Hebner hit 25 home runs, by far the best output of his career.

That season was also marred by an incident involving Hebner and his manager Bill Virdon. Late in a game against the Atlanta Braves, Virdon removed Hebner for defensive reasons, replacing him with career-long shortstop Gene Alley. Hebner was furious. After the game, he confronted Virdon with some words of profanity. Virdon then challenged Hebner to stand up and fight him. Hebner opted not to rise from his seat. The next day, Hebner approached Virdon and apologized.

Hebner’s initial exchange with Virdon indicated his explosive and colorful nature. The tobacco-chewing Hebner liked to pepper his conversations with expletives, part of a gruff exterior that masked a more sensitive personality. He also became something of a celebrity on the local dating scene. He earned a reputation as the city of Pittsburgh’s most eligible bachelor. In one week, he received five marriage proposals. He chose to accept none of the invitations.

On the field, Hebner remained a productive player through the 1974 season. Then came the struggles of 1975 and ’76. Hebner’s hitting fell off, as his average settled into the .240 range. To make matters worse, he hit only eight home runs in 1976. He also heard continuing criticism about his fielding skills at third base. Some members of the media began to question Hebner’s fast-moving lifestyle. Fans at Three Rivers Stadium booed and heckled Hebner, who only made the situation worse by returning the verbal catcalls to the fans.

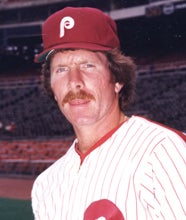

The timing of Hebner’s slump was particularly unfortunate because of his impending free agency. After the ’76 season, Hebner became part of the game’s first free agent class, but he received fewer offers than he initially expected. He ended up signing a multiyear deal worth $600,000 with the Philadelphia Phillies. It was a decent contract for the time period, but far below what Hebner and his agent had anticipated.

With Mike Schmidt at third base, the Phillies had no need for Hebner to play the hot corner. They moved him over to first base. Given Hebner’s declining range, the switch from third to first made perfect sense. Hebner played well for the Phillies in 1977 and ‘78, putting up OPS numbers of .864 and .834 in two seasons, respectively. But during the winter of 1978, the Phillies pursued Pete Rose, signing him to play first base.

The addition of Rose made Hebner expendable. As Spring Training came to an end in 1979, the Phillies alleviated the logjam by trading Hebner and infielder Jose Moreno to the New York Mets for a talented young right-hander named Nino Espinosa.

For the Mets, third base had long been a trouble spot. Deciding to move Hebner back to his original major league position, the Mets hoped that Hebner could fill the void. The plan did not work according to expectation. Hebner struggled in reacquainting himself to the hot corner. More surprisingly, he fell into a bad batting slump, which brought him loud boos from the fans at Shea Stadium.

Beyond his hitting and fielding woes, Hebner’s problems seemed to stem from his new environment. He did not like playing or living in the nation’s largest city.

“I’m just not a big city guy,” Hebner revealed in an interview with The New York Times. “Too much hustle-bustle.”

Bothered by the large crowds of people, the traffic, and a demanding fan base, Hebner never felt comfortable playing for the Mets.

At the end of the season, the Mets moved on from Hebner. They traded Hebner to the Detroit Tigers for a package of two players: Young third baseman Phil Mankowski and veteran outfielder Jerry Morales.

The trade left the Tigers thrilled. They viewed Hebner, with his lefty, pull-hitting stroke as an ideal fit for the short right field porch at venerable Tiger Stadium. Tigers manager Sparky Anderson gleefully announced that Hebner would not only serve as his starting third baseman, but would also bat cleanup for the Tigers.

Greeted with high expectations, Hebner did not deliver exactly that the Tigers had anticipated. Starting the season at third base, he moved to first base when the Tigers dealt Jason Thompson to California. Hebner failed to hit with much power, totaling only 12 home runs. An injured foot also limited Hebner to 104 games. Yet, not all was lost. When Hebner did play, he posted an OPS of .826. A .290 batting average, a .360 on-base percentage and 82 RBIs all represented positive numbers for Hebner.

In 1981, the player strike resulted in a fragmented season. The interruption seemed to affect Hebner more than most; he batted a career-low .226 and hit only five home runs. At 33, Hebner was showing his age.

Not the player he once was, Hebner settled into a platoon with new acquisition Enos Cabell in 1982. Hebner hit well to start the season, but then fell into a slump. With the Tigers falling out of contention, they decided to move Hebner, one of their aging veterans. In the middle of August, they sold Hebner to selling him to his original team, the Pirates.

For the next season and a half, Hebner performed respectably for the Bucs as a pinch-hitter and utility infielder. After the 1983 season, he signed a free agent contract with the Chicago Cubs.

Although he was nearing the end of his career, he impressed manager Jim Frey and his teammates with his enthusiasm. Hebner routinely arrived at the ballpark before any of the other players, even though there was little guarantee that he would play that day. On the field, Hebner excelled in a part-time role. He batted .333 in 45 games, doing his small part to help the Cubs win the National League East. For the first time since his Phillies days in 1978, Hebner returned to the postseason.

In 1985, Hebner came back to play one more season with the Cubs. The following March, he received his release, ending his playing career. To no one’s surprise, Hebner would remain employed within the game. He eventually became a minor league manager for the Toronto Blue Jays, at one point working for their Triple-A affiliate in Syracuse, N.Y. That’s when I had the chance to meet and interview Hebner for the first time. He made quite the impression with his honesty, his down-to-earth personality and his salty language. For those who remember the film Jaws, Hebner comes across as the “Quint” of baseball.

Hebner later returned to the Pirates as a minor league manager and instructor, before eventually returning to the big leagues as a coach with Philadelphia and Boston. He has put in time with several other organizations, too, working at such minor league outposts as Durham, Birmingham, and Buffalo. Now retired from the game, he continues to live in Walpole, Mass.

Still known to this day as “The Gravedigger,” or “Digger” for short, Hebner is one of the game’s good guys, a baseball lifer full of vigor. Whether he’s at the ballpark or at a card show, Richie Hebner is someone who will always give you a good story from a winding life in baseball.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame