- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner 1962 Topps Jake Gibbs

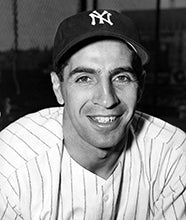

#CardCorner 1962 Topps Jake Gibbs

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Almost everything about Jake Gibbs’ 1962 Topps card strikes me as unusual. First, the card designates him as a “1962 Rookie.” In future years, Topps would almost always group three or four rookies on the same card, sometimes including players from different teams. But in 1962, each rookie player received his own card, along with the special notation, highlighted by a bright yellow star in either the upper right-hand or left-hand corner.

Then there is the position listing, located in small print in the lower right-hand corner of the card. Gibbs is listed as a third baseman, but most of us middle-aged fans remember him as a catcher. In fact, I never knew that Gibbs played third base, either in the minor leagues or the major leagues. But in 1962, Gibbs appeared in all of two major league games, one as a pinch-runner and one at third base. After his debut season, he would play only as a catcher – covering a span of nine seasons – and would never again play an inning at the hot corner.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

While these are intriguing curiosities about the card, the most unusual feature of all is the photograph. Or is it even a photograph? Frankly, it looks more like a drawing. We’ve become used to seeing team colors and logos airbrushed onto a card, but here it looks like Gibbs himself, including his face and perhaps his arms, has been airbrushed. In fact, Gibbs’ entire figure, top to bottom, has been airbrushed.

Why would Topps do that? I can only hazard a guess that Topps had a limited supply of Gibbs photographs and did not have any color photos at its disposal. So perhaps the artists at Topps took the best black-and-white photo that they could find and did their best to colorize it, just like Ted Turner did with some of his favorite old films back in the 1980s. The colorized effect gives Gibbs a surreal texture, making it one of the most unusual cards I’ve seen over the last 55 years.

Given the strange beauty of Gibbs’ 1962 card, it’s inevitable to want to learn more about him. He was a player whom I never saw play, but a name that I would hear frequently on New York Yankees broadcasts. I started watching baseball avidly in 1972, so I missed out on Gibbs by one year. He had abruptly retired after the 1971 season, and his name remained pertinent to Yankee broadcasters Phil Rizzuto, Bill White, and Frank Messer. They talked about him often. For a baseball fan, it’s a little weird hearing so many stories about a player you just missed seeing. In a way, he becomes something of a personal legend. For me, Gibbs was that guy.

As an amateur, Gibbs was a two-sport star at the University of Mississippi. Not only was he a standout shortstop/third baseman, but he was a terrific, record-setting quarterback at Ole Miss, one of the best signal callers in the nation. Many writers speculated that he would opt for a career in the National Football League, but Gibbs preferred the option of baseball. In the days before the draft, he talked to many teams in both sports, including the Chicago Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers, but ultimately chose the Yankees, who gave him a bonus of $100,000 prior to the 1961 season. At the time, it was the largest bonus the Yankees had ever given to an amateur ballplayer.

Given Gibbs’ experience as a college player, the Yankees assigned him to Triple-A Richmond to start his professional career. Playing at second base and third base, he showed few signs of being overmatched. Batting .270 with six home runs in 106 games, Gibbs handled himself well against players who were older and far more experienced. He showed additional improvement in 1962, when the Yankees played him at both third base and shortstop and watched him raise his batting average to .284 while posting a respectable OPS of .742.

Duly impressed, the Yankees brought him up in September of 1962, perhaps too late to justify Topps’ confidence in him, but relatively early for a player of limited minor league experience. Gibbs scored a run in each game he played that fall. He impressed the Yankees with his likeable personality and his work ethic.

The Yankees hoped that Gibbs would soon make the transition to the major leagues fulltime, but his hitting tailed off badly in the minors in both 1963 and ’64, in part because he suffered broken fingers both seasons. The offensive problems also stemmed from another switch in positions, this one more drastic. Liking the idea of a left-handed hitting catcher, Yankees manager Ralph Houk asked Gibbs if he would be willing to become a fulltime receiver, a demanding position both physically and mentally. Gibbs agreed to the change, even though it would stunt his hitting and his health. Over the span of those two seasons, Gibbs batted only .233 and .218, respectively, stalling his development. Each September, the Yankees called him up, but gave him only a smattering of at-bats against major league competition.

Despite the late call-up in 1964, the Yankees planned to include him on their World Series roster against the St. Louis Cardinals. Then came an unexpected setback. In the Yankees’ regular season finale, a meaningless game in the standings, Gibbs suffered a broken finger. Unable to play in the Series, Gibbs saw his roster spot taken by young first baseman Mike Hegan.

All things considered, Gibbs had made a smooth transition to catching, but the lack of hitting mandated another return to Triple-A to start the 1965 season. Gibbs had initially believed that he was out of minor league options, but a technicality in the rules dictated otherwise, disappointing the demoted catcher.

By the middle of June, the Yankees again needed help behind the plate, largely because Elston Howard was starting to show his age. With Howard in decline, Johnny Blanchard slumping and Doc Edwards representing mostly a stopgap solution, the Yankees summoned Gibbs, who continued to put in hours of work with Yankee coach Jim Hegan, at one time a stellar defensive catcher. But manager Johnny Keane played Gibbs sporadically, giving him only 76 plate appearances over 37 games. Not surprisingly, Gibbs hit a mere .221 with negligible power.

By 1966, Howard’s game had fallen off more drastically, giving Gibbs a chance to share the catching duties. He appeared in 62 games and came to bat 182 times, but hit a mediocre .258 with only three home runs.

With nowhere else to turn in 1967, the Yankees made Gibbs part of a strict platoon with the declining Howard. Gibbs made major strides defensively, to the point of drawing the ultimate praise from his manager. “Right now, Gibbs is the best defensive catcher in the league,” Houk told Yankee beat writer Jim Ogle in April. “Before the year is out, the whole league will recognize that fact… He has made himself into an outstanding catcher.”

Gibbs played so well behind the plate that some observers believed he deserved to win the Gold Glove Award. (Instead, the award went to Detroit’s Bill Freehan.) In contrast, Gibbs continued to struggle in his quest to hit for either average or power.

Late in 1967, the Yankees traded Howard to the Boston Red Sox, a move that only confirmed Houk’s confidence in Gibbs. Right after the trade of Howard, Gibbs embarked on a rampage. He picked up 11 hits in 18 times at-bat, while throwing out six consecutive basestealers.

In 1968, Gibbs again did the bulk of the catching, appearing in 124 games, but batted only .213 with three home runs. He continued to struggle at Yankee Stadium, where the short porch in right field proved too tempting. Trying to pull the ball in an attempt to hit home runs, rather than use the entire field, Gibbs often fell into bad hitting habits that only hampered his game further.

While the Yankees had hoped for more from Gibbs, they now realized that he was better suited for work as a backup catcher. They also knew that they had three promising young catchers in the pipeline: Power-hitting Frank Fernandez and minor leaguers John Ellis and Thurman Munson. Gibbs began the 1969 season as the No. 1 catcher, but suffered another broken finger. In the meantime, Fernandez showed power from the start of the season and both Ellis and Munson arrived later that summer, resulting in a loss of playing time for the incumbent.

Gibbs appeared in only 77 games that season, hitting no home runs and seeing his batting average fall off to .224. Practically everyone within the organization anticipated a change in catching for the 1970 season. Munson emerged as the starter, with Gibbs falling into a backup role. As always, Gibbs refused to complain or become bitter. “I kind of knew Thurm was going to do a lot of catching this year,” Gibbs told Newsday. “But my attitude hasn’t changed one way or another. I’ve always been a team man. Sure I want to play. But only nine men can play the game at one time.”

Equipped with such an attitude, Gibbs played well for the Yankees. Ironically, as a second-string catcher Gibbs put together the best season of his career. Receiving some additional playing time when Munson took leave to serve in the Army Reserves for a couple of weeks, Gibbs reached career highs in batting average (.301) and home runs (eight).

With Elston Howard's baseball career coming to a close in 1966 and 1967, Jake Gibbs helped relieve Howard of some of his catching duties. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

After suffering a broken finger in the Yankees' 1964 regular season finale, Jake Gibbs was unable to play in the World Series. He saw his roster spot taken by first baseman Mike Hegan (pictured above). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Yankees manager Ralph Houk (pictured above) had so much confidence in Jake Gibbs as backstop, that he declared him the "best defensive catcher in the league" in 1967. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Given such numbers, Gibbs’ value rose, leading to an inevitable series of trade rumors. Several teams, knowing that the Yankees remained committed to Munson, inquired about Gibbs’ availability. Yankees general manager Lee MacPhail listened to a number of offers, but ultimately bowed to the sentiment of Houk, who wanted to retain his prized backup catcher.

Gibbs continued to serve as the backup in 1971, but his hitting reverted to his earlier career struggles. He batted only .218 in 70 games. Fully aware that Munson represented the present and future behind the plate, Gibbs soon received an offer that would lead to a surprise announcement in June. Still only 32 years old, Gibbs informed the Yankees of his plan to retire, so that he could become the head baseball coach at his alma mater, Mississippi, as well as the school’s chief football recruiter.

Gibbs had remained connected to the school by working as an assistant football coach during the fall, dating back to the mid-1960s. (At one time he had tutored a young quarterback named Archie Manning.) Now his alma mater had stepped up with an offer of fulltime employment. “It was too good an offer to pass up,” Gibbs told Joe Trimble of the New York Daily News. “I think it’s about time to make this move.”

The impending departure of one of his catchers left Houk reeling. “Not only was Jake the best No. 2 catcher in baseball,” the manager told the Sporting News, “but he is one of the best guys anyone could have around a club. He was all man.”

The end of Gibbs’ playing days brought the inevitable question from the media; did he regret the change in position from infielder to catcher? “I think I could have made it as an infielder,” Gibbs told beat writer Jim Ogle. “I had good range and a good arm, but when Ralph asked me to try catching, I did it… I think I would have been a better hitter as an infielder but I got seven [full] years in the majors and can’t kick [about it].”

As a catcher, Gibbs had suffered five broken fingers and a fractured arm. Those injuries affected not only his playing time but also his hitting. Still, he refused to express regret for the change in positions.

He also would have no reason to regret his decision to leave the Yankees and begin his coaching career. In his first year as head coach of Ole Miss, he led the program to the SEC title and a berth in the College World Series, while also earning coach of the year honors. In 1977, he again won the coach of the year award. Remaining at Ole Miss through the 1990 season, Gibbs compiled 485 wins, the most in school history at the time.

After his retirement from Ole Miss, Gibbs eventually returned to baseball, first as a bullpen coach with the Yankees and then as one of their minor league managers. In 1994, he managed the Tampa Yankees of the Florida State League. His roster at Tampa included two prospects named Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera.

In retrospect, that must have been a surreal experience for Gibbs. His 1962 Topps card was certainly surreal, one of the strangest in history. That card marked the start of an unusual career path for the third baseman-turned catcher-turned college coach-turned minor league manager.

Now in retirement, Gibbs can look back with satisfaction at that remarkable career, one that came without any regrets at all.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame