- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

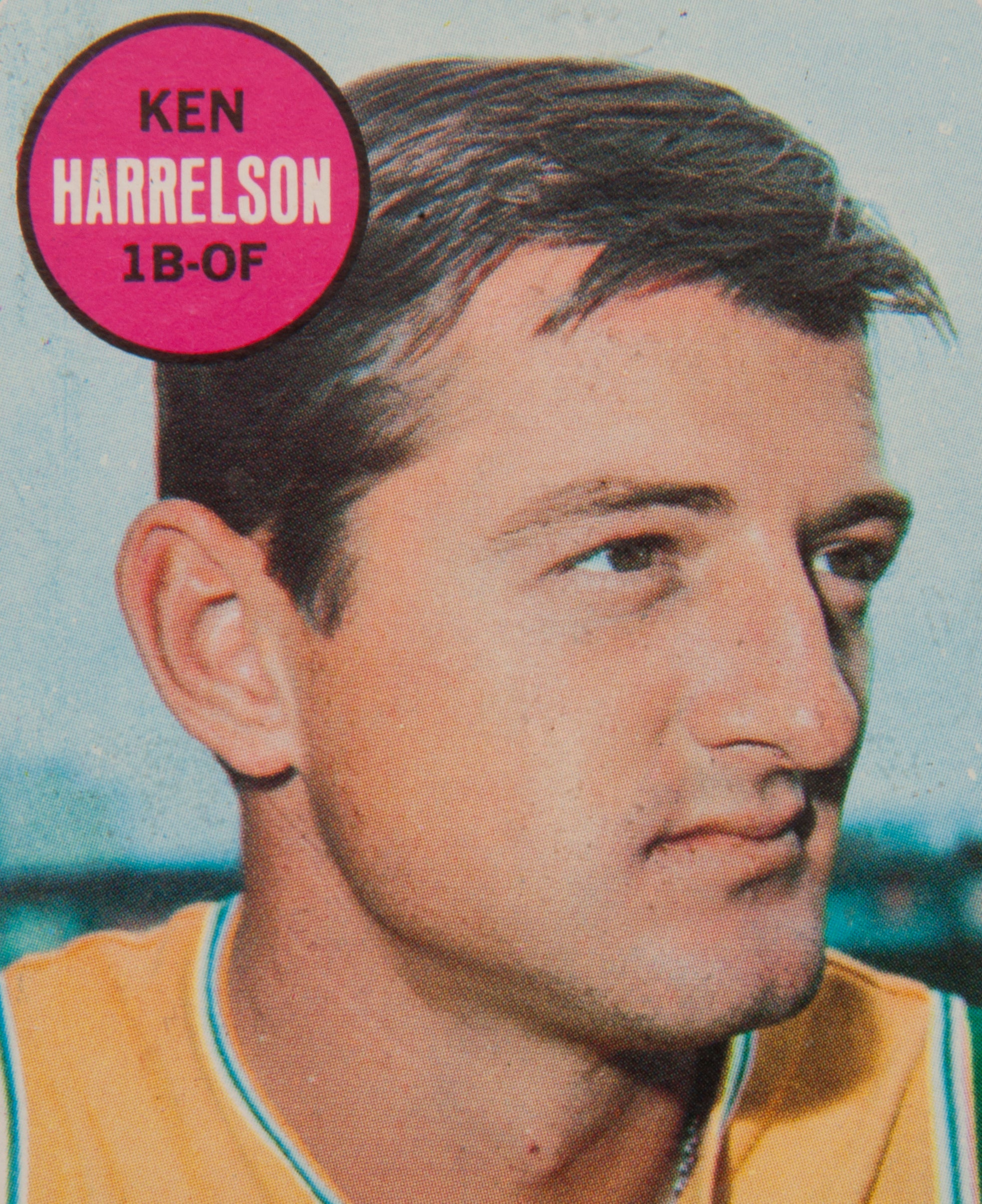

#CardCorner: 1963 Topps Jim Landis

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

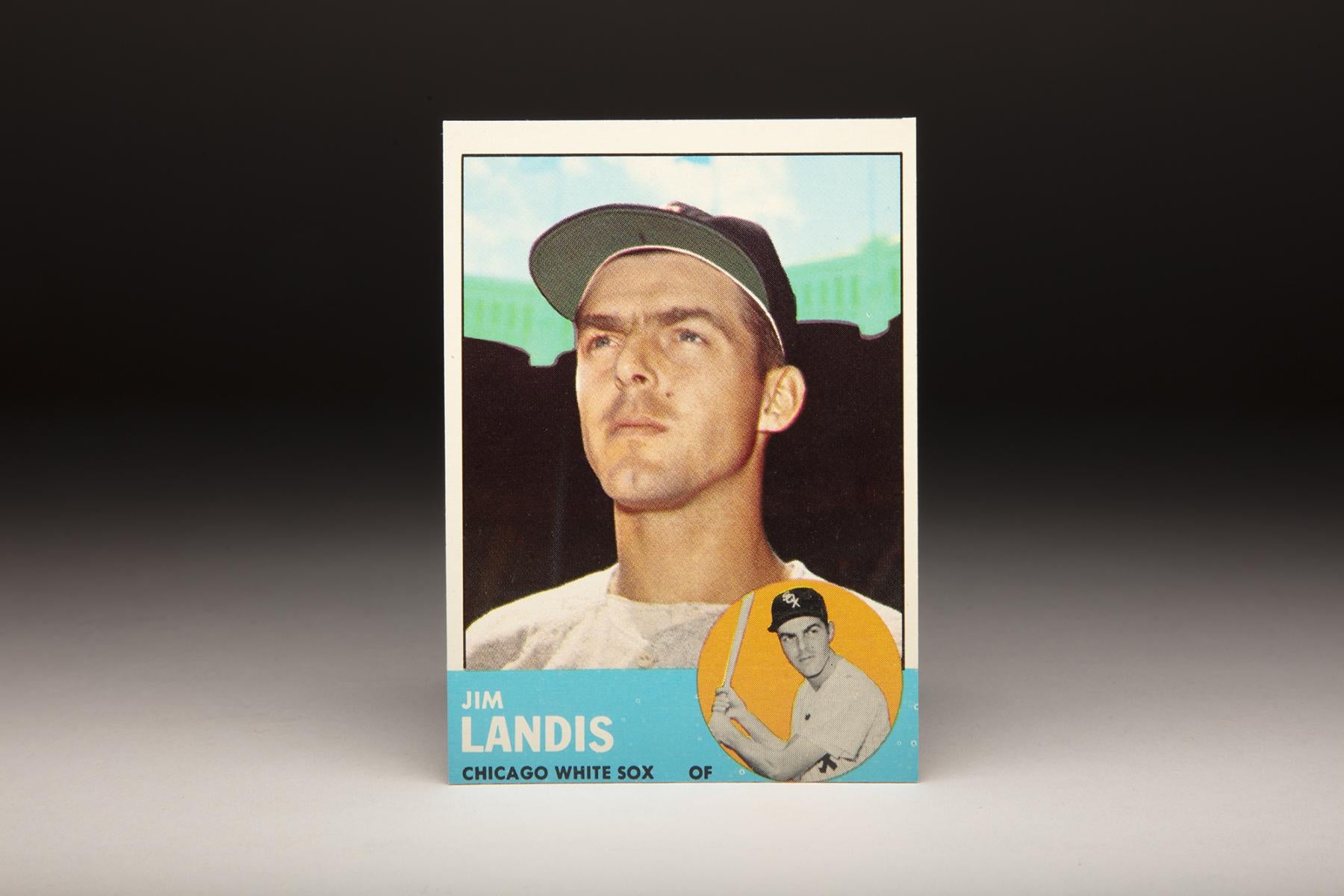

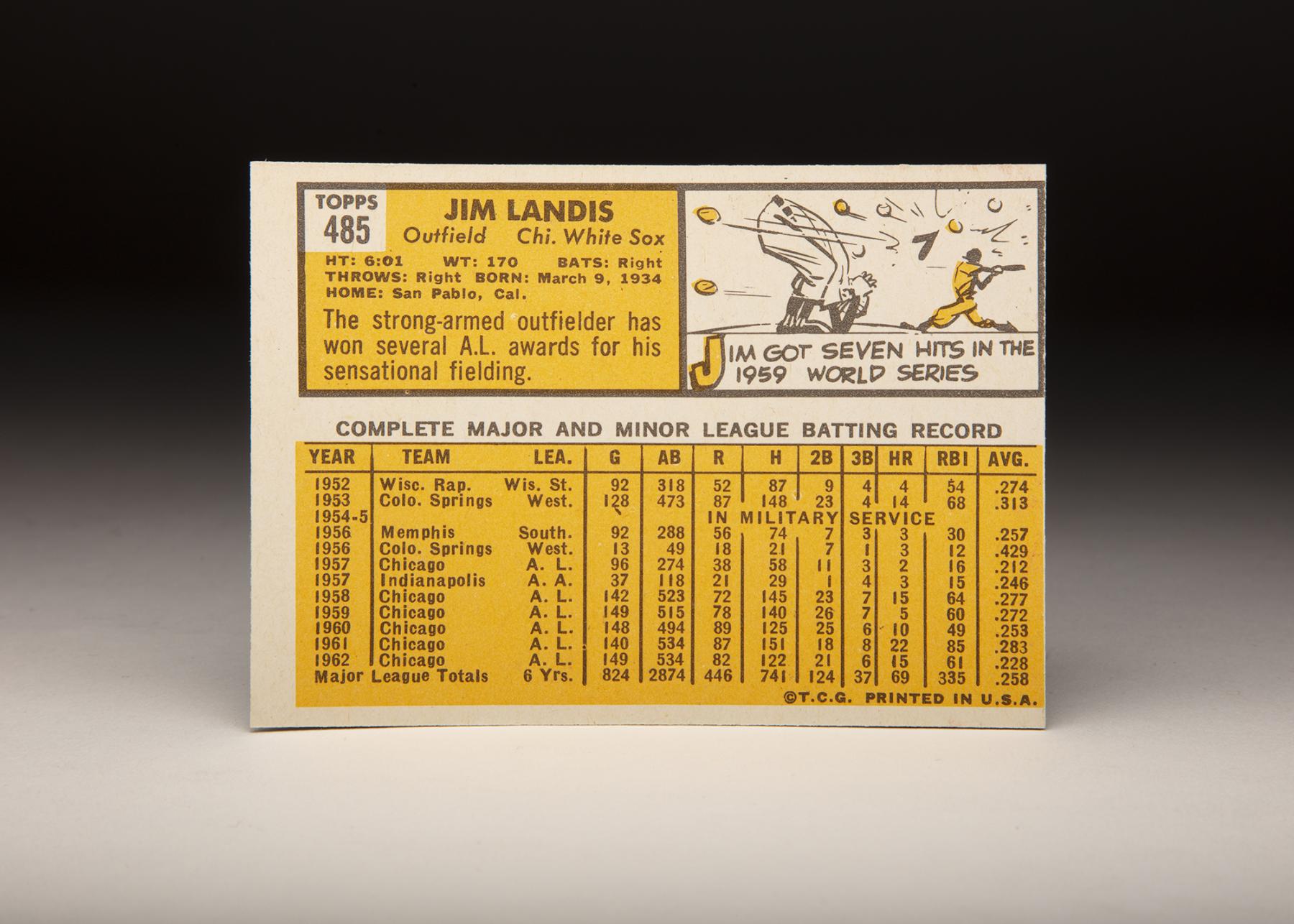

The 1963 Topps set stands out for its bright colors, eye-pleasing design and multiple photographs on the face of each card. Just to add to the intrigue, the set also has its share of unusual examples of airbrushing.

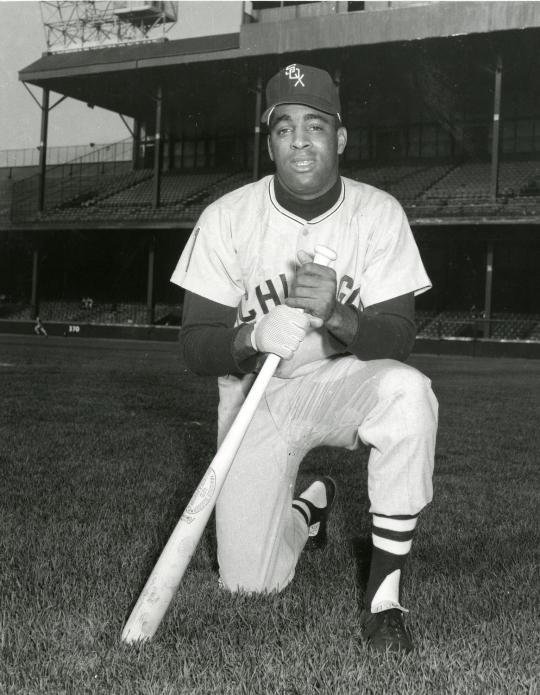

An example of the latter quality can be found on the card of Jim Landis, the terrific defensive center fielder who once roamed Comiskey Park for the Chicago White Sox.

The primary portrait photograph of Landis is a good one. It’s a clear shot that shows the contour of his jawline, the dark patches on his skin, the thick eyebrows, the dimpled chin and even the mole to the right of the nose. But for some reason, Topps has decided to show us Landis with an upturned cap, a trick that the company usually reserved for players who had changed teams over the winter.

I’m not sure why Topps felt motivated to hide the logo from Landis’ cap; it’s not like he switched teams during the offseason. He played for the White Sox in 1962, and then again in 1963. In fact, he played for the franchise continually from 1957 to 1964. Yet, no White Sox logo can be found in the larger picture; it is only in the inset black-and-white photo, the one in the lower right-hand corner surrounded by the gold coloring, that we see the Sox logo on the cap.

Still, there is something even stranger about the Landis card. Look at the top of the card, where the blue sky and the façade (sometimes called the frieze) that ran along the crest of the original Yankee Stadium can be seen. Why is the façade tinted in that bright green color, when most of us remember it as white, and why does the façade seem so blurred and fuzzy? If the photo was indeed taken at Yankee Stadium, why did Topps present the façade in such a surreal way?

Well, the façade, which is now white, was green at the time. So while the fuzzy nature of the image may be a mystery, it was an accurate depiction of the color.

For Landis, it was the most interesting card that came out during his professional career, a career that dated back to 1952, when the Sox signed him as an amateur free agent. It took him a while to make the major leagues – five years in total – in part for reasons having nothing to do with baseball. But his delayed journey through the minor leagues eventually paid off in a trip to Chicago.

When the Sox signed Landis to his first contract, they used him initially as a third baseman before converting him to the outfield. He played well over his first two professional seasons, and learned how to play center field under the direction of former big league outfielder Johnny Mostil. But then came an interruption. He missed all of the 1954 and ’55 seasons while stationed in Alaska as part of his service in the U.S. Army.

Having lost two seasons of development, Landis did his best to make up for lost time. In 1956, he began the season at Colorado Springs in the Class A Western League, where he hit a cool .429.

The Sox then moved him up to Double-A Memphis in midseason. He batted only .257 with three home runs in Double-A, but played a very good center field.

Reporting to Spring Training in 1957, Landis played so well that he made the Sox’ Opening Day roster.

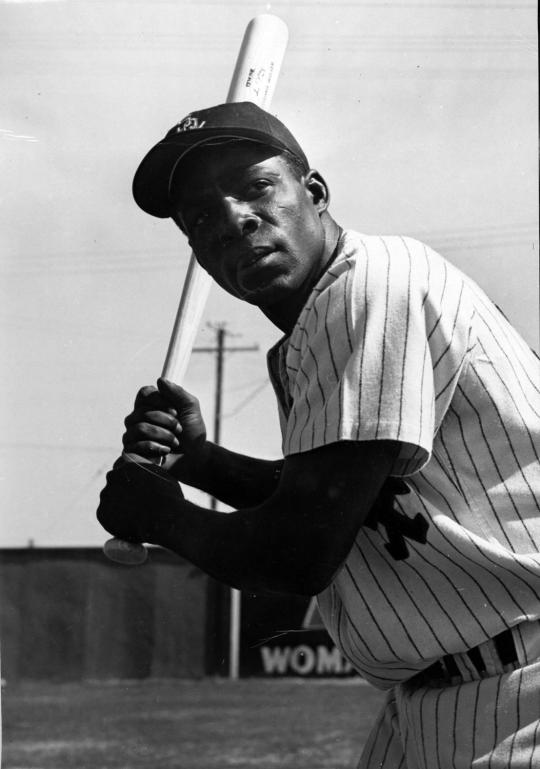

He was overmatched at the plate, forcing him to spend some time in Triple-A ball, but his defensive prowess and his ability to play all three outfield spots made him a valuable backup to Minnie Miñoso, Larry Doby and Jungle Jim Rivera.

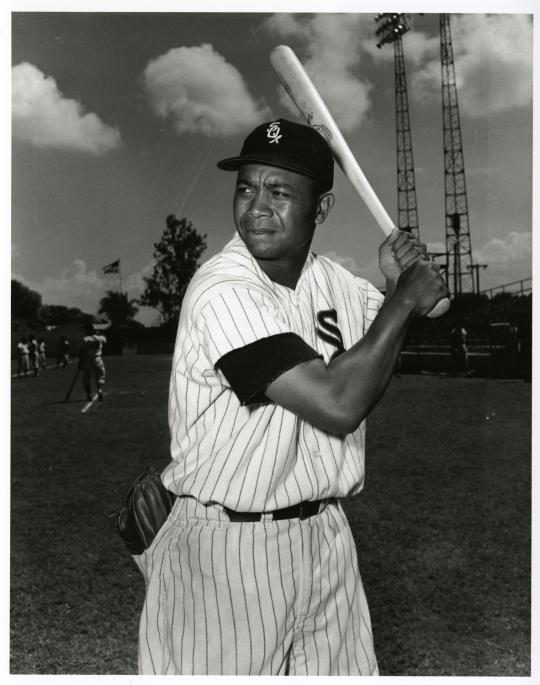

In 1958, the White Sox completely retooled their outfield.

They traded Doby and Minoso and eventually moved Rivera into a backup role. The changes opened up center field for Landis, who responded by batting .277, posting an on-base percentage of .351 and hitting 15 home runs.

When asked about his improved hitting, Landis gave the Sporting News a simple answer. “I just opened my stance a bit. These clubs were pitching me on the wrists and getting me out. Now when they pitch me on the wrists, I have a surprise for them.”

Built long and lean, Landis also contributed in other ways, stealing 19 bases and playing an outstanding center field. At 24 years of age, Landis’ speed, range, and above-average throwing arm gave him a stranglehold on center field at Comiskey Park.

Landis’ power would fall off in 1959, but the rest of his game improved. Despite missing some time in September with a leg infection, he walked 78 times against only 68 strikeouts, lifting his on-base percentage to .379. He also stole 20 bases and continued to catch everything within reach.

With Landis anchoring the defense and fitting perfectly into the White Sox’ “run and stun” attack, he emerged as a major factor for the “Go Go Sox,” who surprised most observers by winning the American League pennant. The league’s beat writers recognized Landis’ performance, giving him strong MVP consideration and placing him seventh in award balloting at season’s end.

In particular, Landis’ range in center field drew praise from scouts and other talent evaluators. Lew Fonseca, a lifelong baseball man who pioneered the use of film and video technology in scouting, offered up the ultimate comparison. “Defensively, I put him close up to Joe DiMaggio and Willie Mays,” Fonseca told Curley Grieve of the San Francisco Examiner. “I’m not sure he shouldn’t be rated the most valuable player for the White Sox.”

Even though the Sox would lose the World Series to Los Angeles, Landis continued to hit well. Playing in all six Series games, he batted .292 with a .346 on-base percentage, as the Sox fell just short of a world championship. In 1960, Landis saw his batting average fall to .253, but he continued to walk at a high rate and finally received some recognition for his defensive play in center field.

The league’s managers and coaches voted him a Gold Glove Award, marking the first of five straight honors for the fleet center fielder. While Landis had a typically fine season, the White Sox as a team failed to play up to their 1959 standards, settling for a third-place finish in the American League pennant race.

Landis would assemble his best individual season in 1961. He hit 22 home runs, an improvement of seven over his best prior output, and also reached career highs in batting average, slugging percentage and OPS. If the Sox had performed better as a team, Landis might have received some support in the MVP voting, but he settled for a second consecutive Gold Glove Award.

For some reason, Landis was left off the American League All-Star Game roster that summer, but he would achieve that honor in 1962. In fact, he was selected to both of the Midsummer Classics, despite enduring a season in which his batting average dropped to .228. But his home run and walk totals remained impressive, as did his fielding. As teammate Al Smith told sportswriter Jerome Holtzman about Landis’ play in center field: “There isn’t anyone better than Landis… I’ve got to take Landis over anybody in this league, and probably over [Willie] Mays, too.”

In 1963, Landis won another Gold Glove Award while putting up similar offensive numbers to what he had done in ’62. It would be his last productive season. In 1964, Landis’ game took a turn to the south. He batted only .208 with just one home run, and given his lack of hitting, he played in only 106 games. Suspecting that he was an “old 30,” the White Sox traded him that winter as part of a complicated three-way deal that sent Rocky Colavito to Cleveland and also involved future stars Tommie Agee and Tommy John.

Once the dust settled, Landis found himself in Kansas City playing for the Athletics. The A’s believed that Landis had enough speed and range left to cover the vast center field territory at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City. They made him their starting center and watched him hit slightly better, with an average of .239 and on-base percentage of .349. But his power left him and his defensive skills fell off. So it came as no surprise that the A’s traded him that winter, sending him to the Cleveland Indians as part of a deal that brought Joe Rudi into Charlie Finley’s fold in Kansas City.

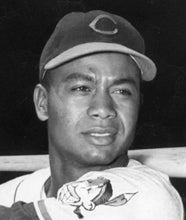

By now, Landis had been rendered a backup. He filled that role in Cleveland for one season and then spent a fragmented 1967 season with three teams (Houston, Detroit and Boston). His stint in Boston lasted only five games, coming to an abrupt end when the Red Sox signed his former A’s teammate, Ken “Hawk” Harrelson.

Although Landis was only 32, he knew that it was time to retire. He went to work for a company that made safety signs designed to prevent industrial accidents, but remained connected to baseball as a Babe Ruth League coach. In his later years, he enjoyed retirement in Napa, Calif., where he passed away in 2017 after a battle with cancer.

Like many players who enjoyed their peak in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Landis has become somewhat forgotten by time. His case is also hurt because much of his value resided with his defense, and there is little film of his fielding exploits. His career also predated the era of advanced metrics. As such, we must rely mostly on the testimony of others, along with those Gold Glove awards, when learning about the capabilities of Landis in the field.

There have been many great defensive center fielders since the 1950s, including Mays, Paul Blair, Cesar Geronimo, Garry Maddox, Devon White, Andruw Jones, and two players from today, Kevin Kiermaier and Kevin Pillar, just to name a handful. Who was the best? Well, that’s difficult to say, but if you listen to those who saw him play, Jim Landis deserves at least a mention in the conversation.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame