- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1958 Topps Marv Throneberry

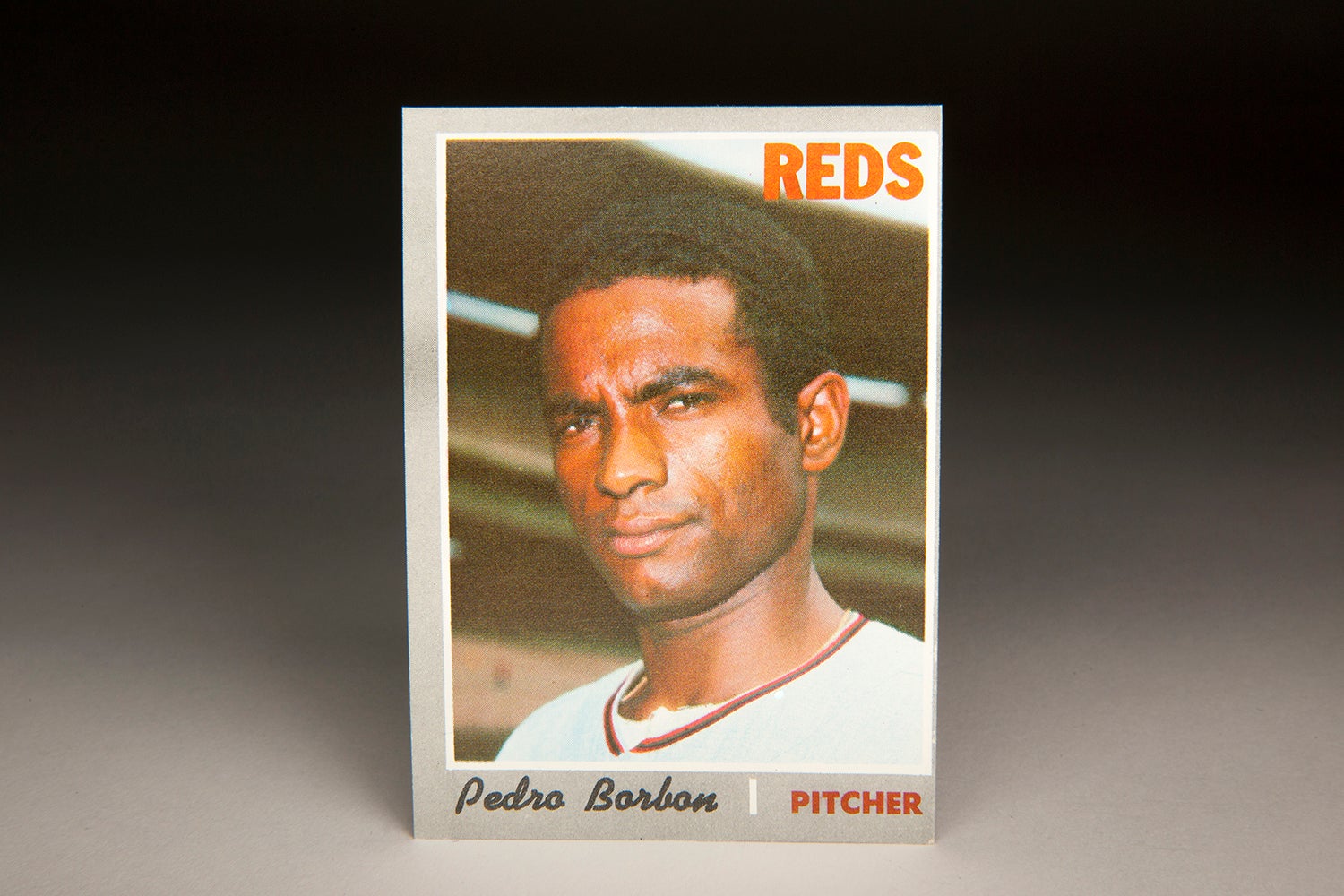

#CardCorner: 1958 Topps Marv Throneberry

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

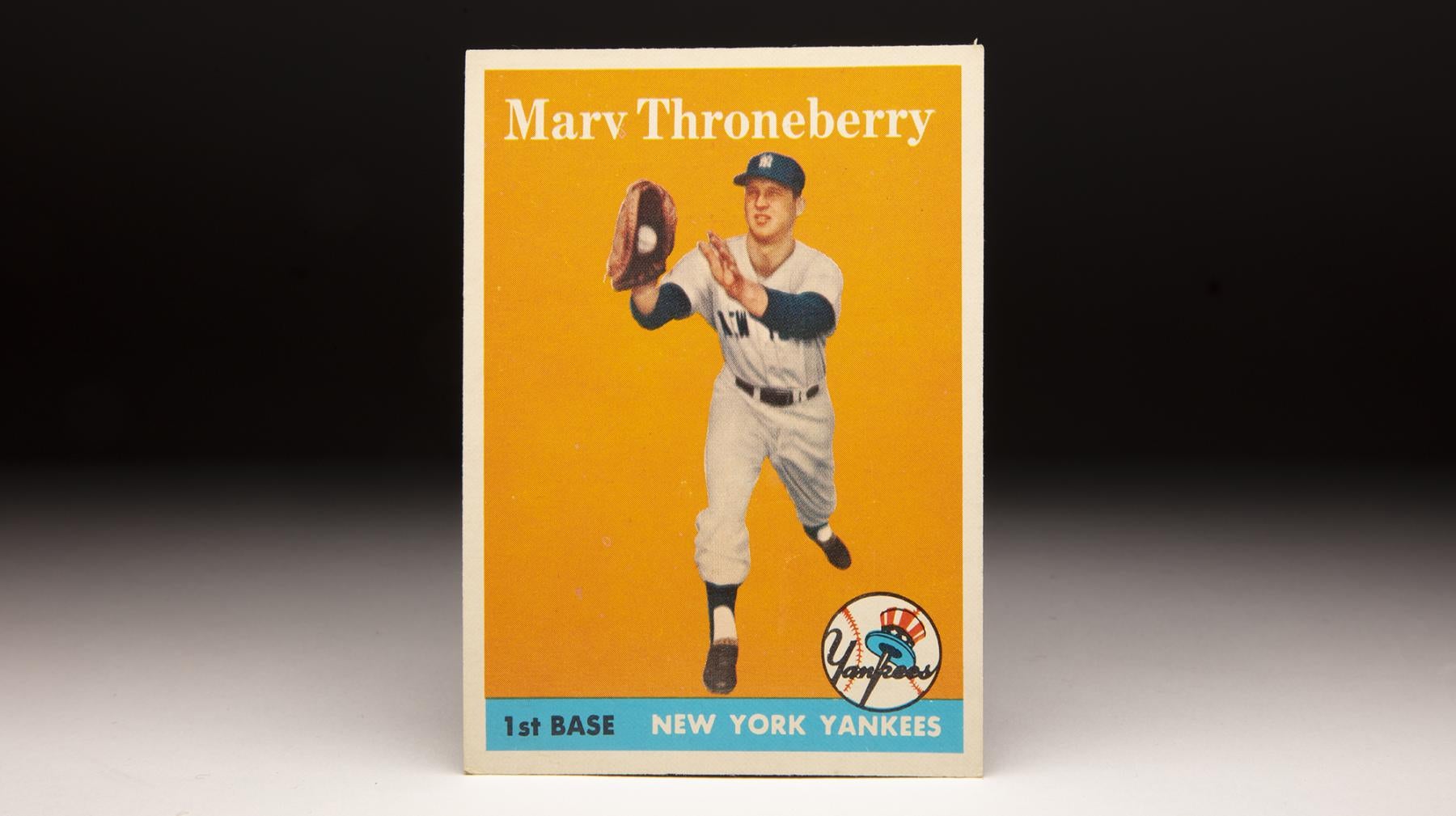

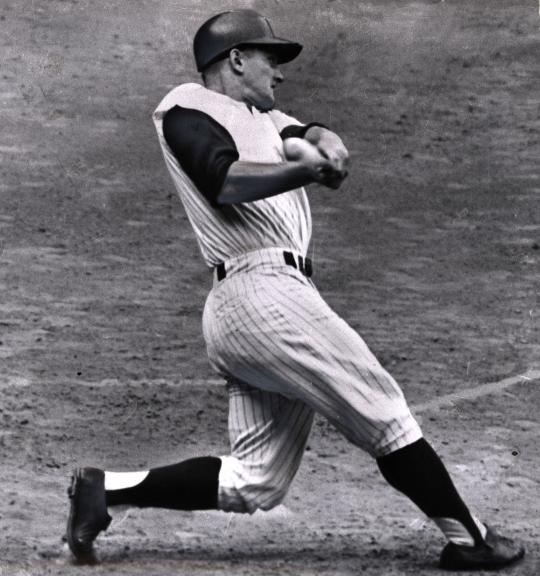

It is just so tempting to look at this 1958 Topps card and joke, “Remarkably, Marv Throneberry did not drop the ball!”

Outside of Bob Uecker, no player has ever made more fun of himself than Throneberry, who carved out a healthy living by telling us how bad he was at baseball. Throneberry liked to exaggerate his ineptitude, of course, but it only made him all the more endearing to fans, even those (like me) who never saw him play.

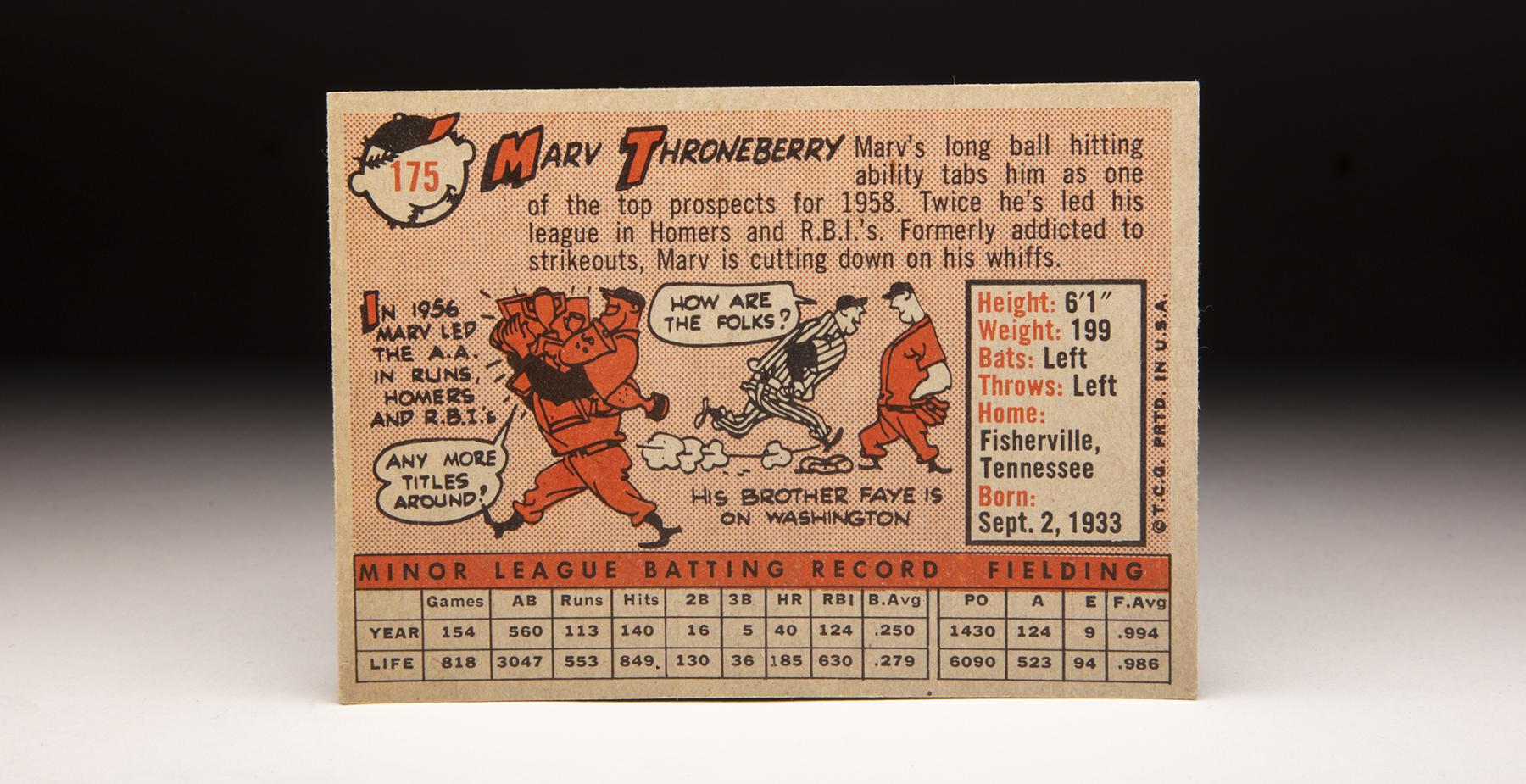

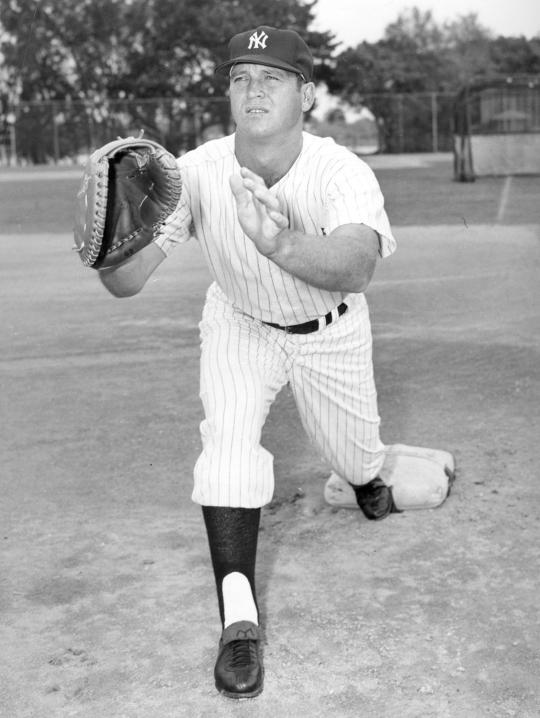

On the other hand, Throneberry is not exactly displaying textbook form in catching a ball (or simulating a catch) on his ’58 rookie card. For some reason, he is holding the ball in the middle of his first baseman’s mitt, where it could easily pop out, as opposed to the proper way of corralling the ball in the webbing of his mitt. And why exactly is Throneberry reaching for the ball with not only his glove hand, but his bare hand, which he is holding up, perhaps in an effort to protect his face?

This might be good form in trying to catch a football, but it seems like an odd way for a first baseman stretching to receive a throw from one of his infielders. If this was the way that Throneberry normally played first base, then perhaps his propensity to make errors becomes more understandable.

Then again, maybe Throneberry was just having fun in posing for his Topps card. Given the way that he is holding up his bare hand and squinting his eyes, good ole Marv might have been trying to create the illusion of a man stumbling in the dark as part of an inept effort to make a simple catch. That would have been Marv through and through.

By the 1970s, Throneberry’s act of self-deprecating humor had become an art form, so much so that Miller Lite Beer sought him out to do a series of commercials for their product. Throneberry made his first Miller Lite commercial in 1976, when he joked that “it used to take 43 Marv Throneberry baseball cards to get you one Carl Furillo.” After espousing the virtues of Miller Lite, Throneberry delivered his closing line perfectly: “If I do for Lite beer what I did for baseball, I’m afraid that their sales might go down.” And with that, Marv Throneberry, after becoming forgotten by most of the American public, became a national television star.

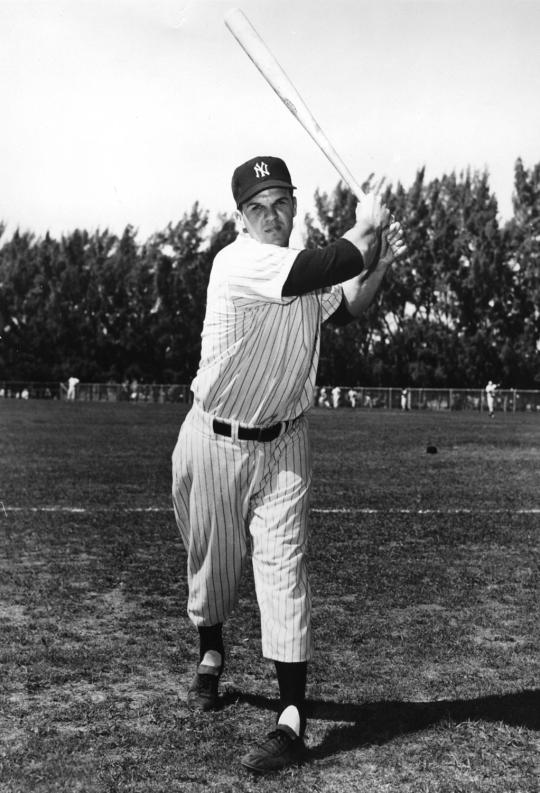

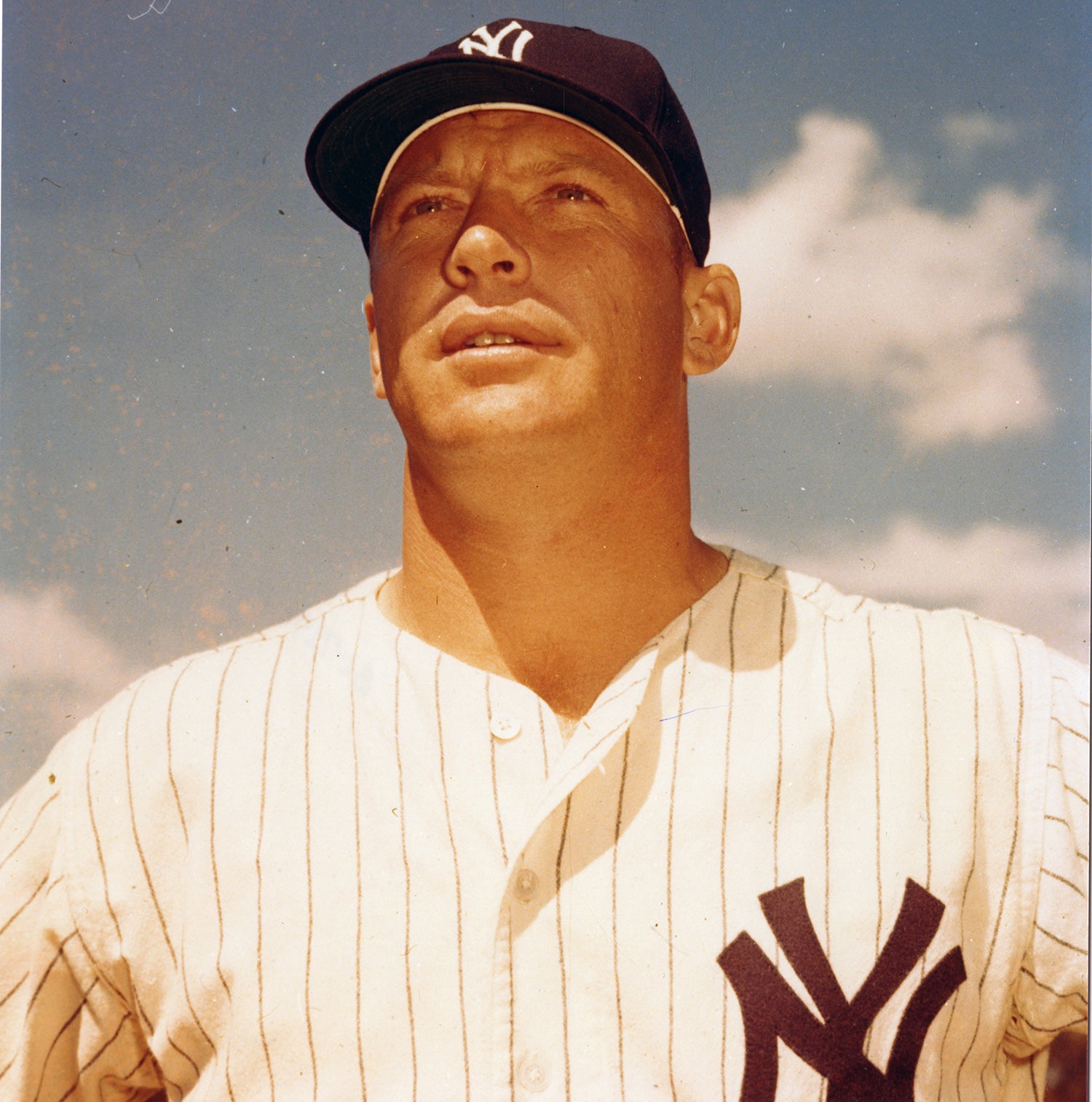

Back in 1958, Throneberry took a more serious approach to his ballplaying ability. He was about to embark on his first full season as a big leaguer with the New York Yankees, the team that signed him out of South Side High School in Memphis. He signed with the Yankees after turning down an offer from the rival Boston Red Sox, who already employed Marv’s brother, Faye.

By ’58, the Yankees hoped that he would become their everyday first baseman. The Yankees had good reason for such hope. In 1957, Throneberry had hit 40 home runs for Triple-A Denver, the Yankees’ top minor league affiliate. While Denver’s altitude has always elevated the statistics of hitters, Throneberry’s 111 walks indicated discipline and knowledge of the strike zone.

The previous year, Throneberry had won the American Association’s MVP Award, also for Denver. Over the span of three seasons, he put up consistently big numbers for Denver, making himself into a legitimate prospect. By 1958, “Marvelous Marv” seemed ready for his first extended taste of major league pitching.

Throneberry’s professional odyssey had begun in 1952, after the Yankees signed him to his first contract and sent him to Quincy of the Three-I League. Hitting with power at each minor league stop over the next four seasons, Throneberry earned a cup of coffee with the Yankees in 1955, when he appeared in one game, collecting two hits in two at-bats (and three RBI) to give himself an early batting average of 1.000.

In 1958, Throneberry returned to the major leagues in a more permanent way. The Yankees kept their young left-handed slugger as a backup to Moose Skowron, a right-handed hitter of ample ability. Throneberry started the season as a pinch-hitter, but an injury to Skowron gave him a chance to play more regularly for much of May. For the season, Throneberry appeared in 60 games and hit only .227, but did flash some power with seven home runs and showed patience with 19 walks.

The Yankees continued to use Throneberry as a backup to Skowron in 1959, but also gave him occasional duty in left and right field. When Skowron suffered a broken wrist in midseason, Throneberry moved into the starting lineup. He raised his batting average to .240 and hit eight home runs, but the strikeout became his weakness. He struck out 51 times in 192 at-bats, a rate that might be accepted in today’s game but was generally not tolerated in the 1950s.

As Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn noted, Throneberry tried to emulate the style of his most famous teammate. “He looked like Mickey Mantle, walking to the plate,” said Ashburn, who would play with Throneberry during his later Mets tenure, in an interview with Jack Lang of the New York Daily News. “I think Marv actually copied Mickey’s style, his walk and all that. But it ended when he got to the plate.”

Convinced that Throneberry would never make the kind of regular contact they wanted to see, the Yankees included him in a major trade in December of 1959. Along with Hank Bauer, Norm Siebern and Don Larsen, Throneberry went to the Kansas City Athletics in the deal that brought Roger Maris to New York. The trade would take on historic ramifications, but not because of anything that Throneberry did. That would all rest with Roger Maris.

Joining the talent-poor A’s, Throneberry became Kansas City’s regular first baseman against right-handed pitching. In 104 games, he batted .250 with 11 home runs, modest numbers to be sure – but his OPS of .760 ranked third among all A’s regulars. Throneberry returned to the A’s in 1961, but he did not show the kind of improvement that Kansas City wanted to see. In early June, just before the trading deadline, the A’s moved on from Throneberry, sending him to Baltimore for veteran outfielder Gene Stephens.

With veteran slugger Jim Gentile entrenched at first base, the Orioles hoped that Throneberry would provide a fit in their outfield, which desperately needed a power hitting boost. It didn’t happen. He ended up with five home runs in 96 at-bats, while his batting average sunk to .208 and his slugging percentage fell below .400.

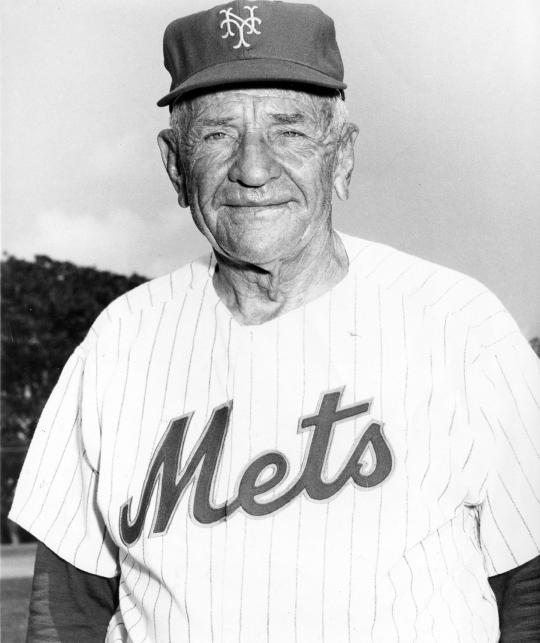

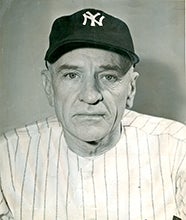

The Orioles gave Throneberry another look in 1962, but he went hitless in 13 early season plate appearances. In May, the Orioles traded him, finding a taker among one of the two new National League expansion clubs. In search of young power hitters, the New York Mets acquired Throneberry, surrendering catcher Hobie Landrith. The trade reunited Throneberry with Casey Stengel, his onetime manager with the Yankees.

Throneberry found a little bit of success, and plenty of fame, with the Mets, who needed help at first base because of an injury to Gil Hodges. On the surface, his hitting numbers looked more than decent, especially for an expansion club: a team-leading 16 home runs and a .426 slugging percentage in 116 games. But Throneberry had problems defensively, in part because of a knee injury, committing 17 errors in 97 appearances at first base. He also made numerous mistakes on the basepaths.

Perhaps his most famous baserunning blunder occurred in a game against the Chicago Cubs. The date was June 17, the first game of a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds, where the Mets played home games during their inaugural season. With two runners on in the bottom of the first, Throneberry belted a long drive toward the Mets’ bullpen. Driving in teammates Gene Woodling and Frank Thomas, Throneberry legged out what appeared to be a two-RBI triple. But Cubs first baseman Ernie Banks noticed that Throneberry had missed the first base bag and called for the ball. Banks stepped on the bag, prompting umpire Dusty Boggess to call “Out!”

Casey Stengel came out to argue the play, contending that Throneberry’s foot had come in contact with the bag. According to an account in the New York Daily News, as Stengel and the first base umpire continued their argument, Mets coach Cookie Lavagetto ambled over to join the conversation. “Don’t argue too much, Casey,” said Cookie. “I think he missed second base, too.” Boggess confirmed that Lavagetto was right. That prompted Stengel to yell, “Well I know one thing. He damn well didn’t miss third because he’s standing on it!” And with that, the conversation came to an end.

Because of missteps like this, Throneberry became the symbol for a Mets team that lost 120 games. At several points in 1962, Stengel said of his Mets players, “Can anybody here play this game?” Perhaps more so than any other member of the Mets, Throneberry became the player most associated with Stengel’s famous line. With Throneberry’s propensity for the on field faux pas becoming a recurrent theme, Mets fans booed him regularly and serenaded him with catcalls during the 1962 season.

But as the season progressed, something strange occurred. He actually began to develop a cult following among some Mets fans, who noticed that Marv’s initials appropriately spelled out “MET.” A particularly rabid group of fans formed the Marv Throneberry Fan Club, which numbered roughly 5,000 members at its high point. The members of the club wore shirts that spelled out “VRAM,” which was simply “MARV” spelled backwards. In attending Mets games at the Polo Grounds, the fan club members regularly chanted “Cranberry, strawberry, we love Throneberry!”

Throneberry’s easygoing personality also made him popular with teammates and the media. Even as the butt of season-long jokes, Throneberry never once complained about the situation. After the season ended, the New York writers rewarded Throneberry by naming him the winner of the Ben Epstein “Good Guy” Award. The award was named for a popular New York writer who had died in 1957.

In January of 1963, Throneberry traveled to New York to officially accept the award. As he accepted the Epstein plaque, Throneberry delivered a memorable ‘thank-you’ to the audience. “I was a little afraid to come up and get this for fear I might drop it.” The audience exploded in laughter.

Still hoping that Throneberry might improve his baserunning and defensive play, the Mets brought him back for the 1963 season, but they also hedged their bets by acquiring Tim Harkness from the Los Angeles Dodgers. Harkness won the first base job during the spring, leaving Throneberry to start the season as a pinch-hitter who rarely played. In early May, the Mets demoted him to their minor league affiliate at Buffalo, where he showed power but batted only .169.

Throneberry would never make it back to New York. In 1964, he returned to Triple-A Buffalo, picked up one hit in 12 at-bats, and drew his release. At the age of 30, his career had come to an end.

For the most part, Throneberry fell out of the public consciousness – and out of baseball. He went to work for a beer distributor and also took classes that helped him learn about selling insurance. That all changed in 1975 when he received a midnight phone call from an advertising executive. The man offered him a chance to appear in one of Miller Beer’s new line of commercials featuring retired athletes.

Throneberry, with his laid-back style and willingness to poke fun at himself, emerged as a natural on the television screen. Miller Lite asked him to do additional commercials. In most of those 12 follow-up commercials, Throneberry delivered his memorable closing line in matter-of-fact fashion: “I still don’t know why they asked me to do this commercial.” As part of his contract with Miller Lite, Throneberry made public appearances around the country, each one paying him in the range of $1,200 to $1,400. Throneberry did so well with Miller Lite that he was able to quit his full-time job working for a firm specializing in insulating glass.

The talk show circuit also came calling. Throneberry became something of a cult star, admired for his down-home personality, his innocence, his sense of humor and his willingness to take good-natured verbal shots at himself. Marv Throneberry became fashionable again – and helped Miller Lite execute one of the most successful advertising campaigns in television history.

In a 1982 interview with the Associated Press, Throneberry was asked why he so willingly mocked himself during his many appearances and commercials. His answer was refreshingly forthright. “Cause I’m making commercials, making public appearances, and going to work just two times a month and making a great living,” Throneberry told the AP. “I can fish four or five days a week. I’ve got five boats and five motors. I don’t have to worry about things I used to worry about. I wouldn’t trade this for anything.”

At one point, NBC planned to do a made-for-TV movie featuring the Miller Lite stars, including Throneberry. The movie, billed as a comedy, would have taken on the feel of the "Smokey and the Bandit" films. Throneberry was supposed to play a character who invents a water substitute for gasoline, resulting in a madcap battle for the formula. But the film never did come to fruition. Throneberry would have to settle for guest appearances on "Saturday Night Live" and a 1985 Rodney Dangerfield comedy special.

Even though the made-for-TV movie did not become a reality, Throneberry continued his association with Miller Lite into the early 1990s. It seemed like he would have a long career as a beer spokesman and talk show guest, the second coming of Uecker, if you will, but then came the terrible news: A diagnosis of cancer. On June 23, 1994, Throneberry lost his battle with the disease. He was only 60.

Throneberry has been gone a long time now, but his legacy remains evident. One of his grandchildren, Craig Brewer, is a successful film maker who has directed such movies as "Hustle and Flow" and several episodes of the "Empire" TV series. Throneberry’s old Miller Lite commercials can still be found on YouTube. And yes, his baseball cards are not only available, but very affordable, including that 1958 rookie card, when he gave us a hint of the mishaps and the fun that was still to come.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame