- Home

- Our Stories

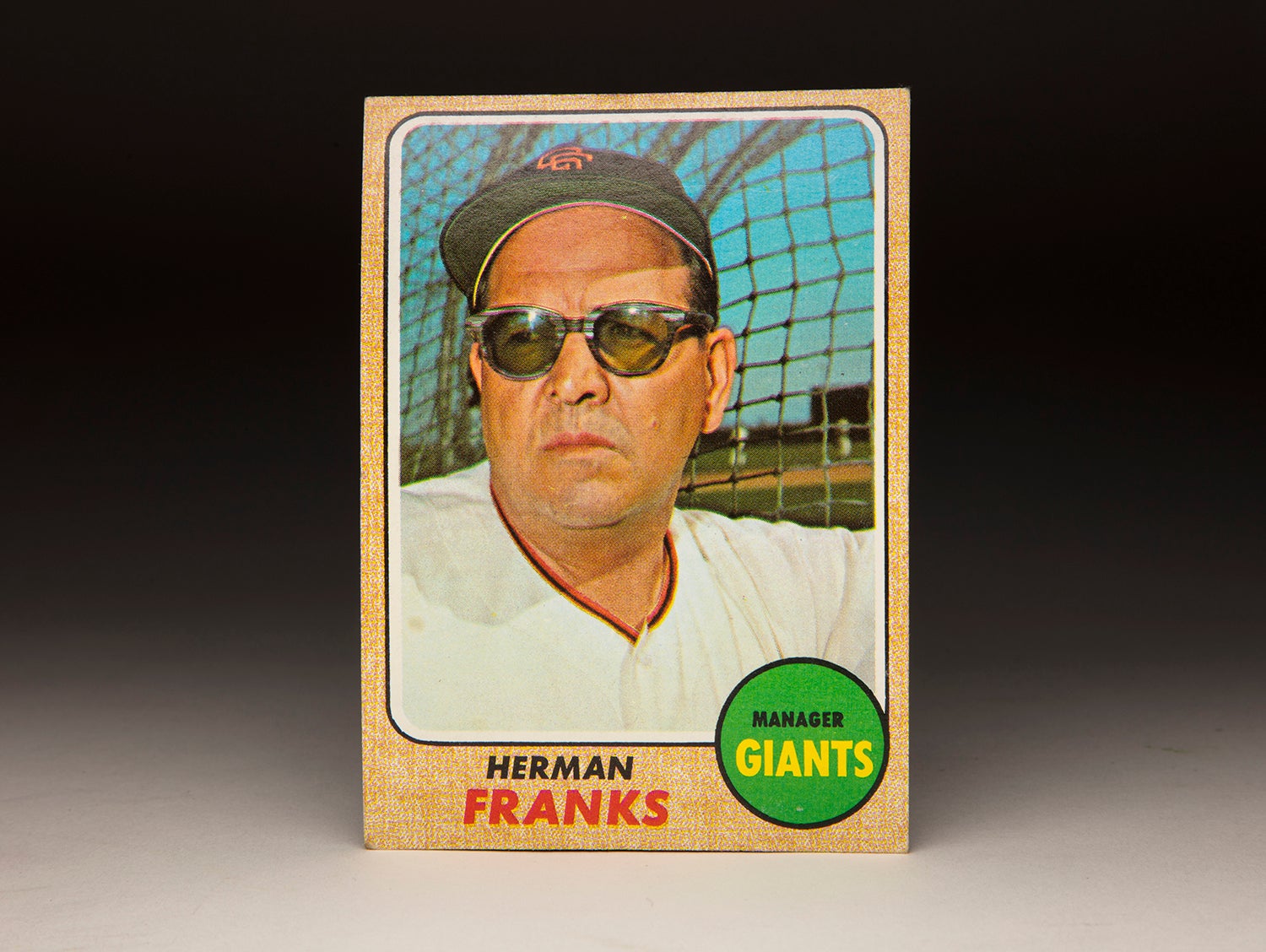

- #CardCorner: 1968 Topps Pete Richert

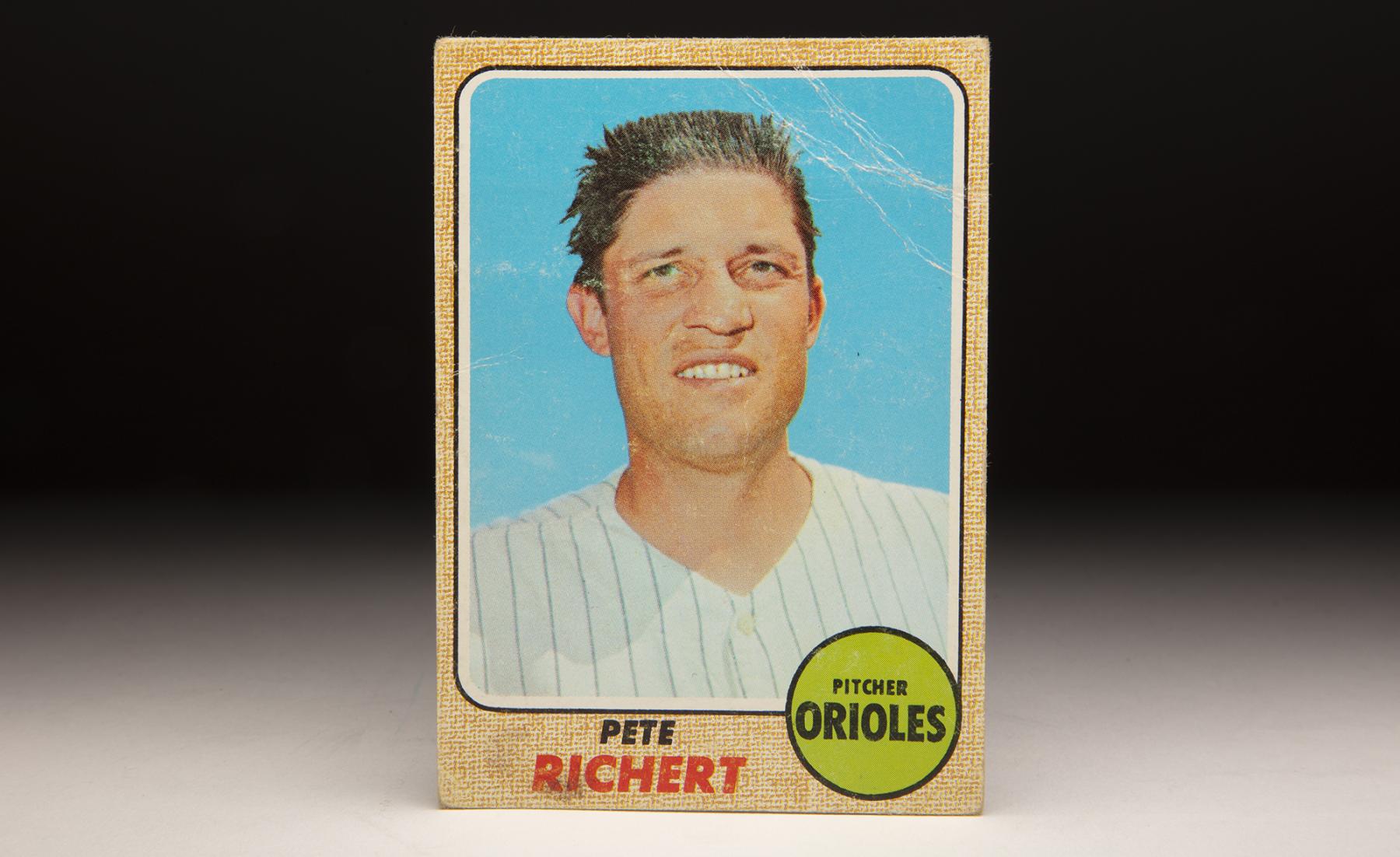

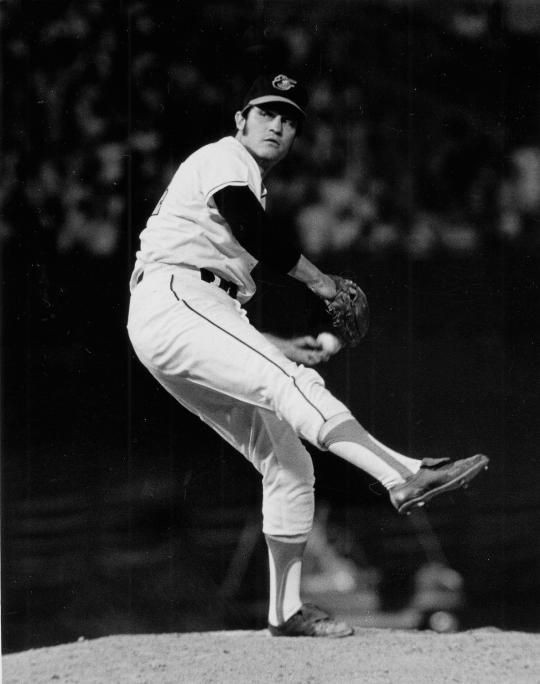

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Pete Richert

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Growing up, I had bad hair. To borrow a phrase from Colonel Henry Blake of "M*A*S*H", my hair was so thin I could have combed it with a towel. Even then, it was still a scattered mess.

So when I saw Pete Richert’s 1968 Topps card, my thoughts went immediately to my childhood hair. Of course, in Richert’s case, he is a fully grown adult, so it would have been difficult for him to say, “I’ll grow out of it,” as I used say.

In actuality, the Topps photographer has probably just caught Richert at an inopportune moment, fresh off a bad haircut and a hot spring day of wearing a cap over the head.

Like many players of the 1960s, Pete Richert (pronounced RICK-ert) is wearing his hair in a short, military style cut. (Major league players did not start to wear their hair long until the early 1970s, a good half-decade after it became fashionable for American men to do so.)

If you press a cap over that kind of hair, allow the perspiration to accumulate for a while, and then suddenly remove the cap without brushing your hair, the end result is a spiked effect with a few loose strands hanging off the side. That’s exactly what we see with good ol’ Pete. Ah, the perils of being a ballplayer and having your photograph taken on short notice.

There is one other oddity to Richert’s 1968 card. The uniform he is wearing has pinstripes, but the designation on the card is “Orioles.” Of course, Baltimore did not wear pinstriped uniforms back in the mid-1960s. The uniform in question is actually the home jersey of the Washington Senators; that was the team that Richert was pitching for when this photograph was taken, likely during Spring Training in either 1966 or ’67.

In the 1960s, it was common for Topps to take photographs of players without caps. The photographs especially liked to do this with players who were not stars. Star players generally stayed with the same team year after year, but if you were something other than a star, there was that very real possibility of being traded. Topps figured that by taking a capless photo of journeymen, or common players, the photo would still hold even if the player were to be traded during the next calendar year. In Richert’s case, the capless look provided cover for the trade that sent him from the Senators to the Orioles.

For a well-traveled pitcher like Richert, the capless photo made particular sense. Over the span of 13 seasons, he made six stops, including five with different organizations. That is not to say that Richert was a bad pitcher – not at all. Some players who are not very good are traded often; others are traded often because they are very good. The latter description applies to Richert.

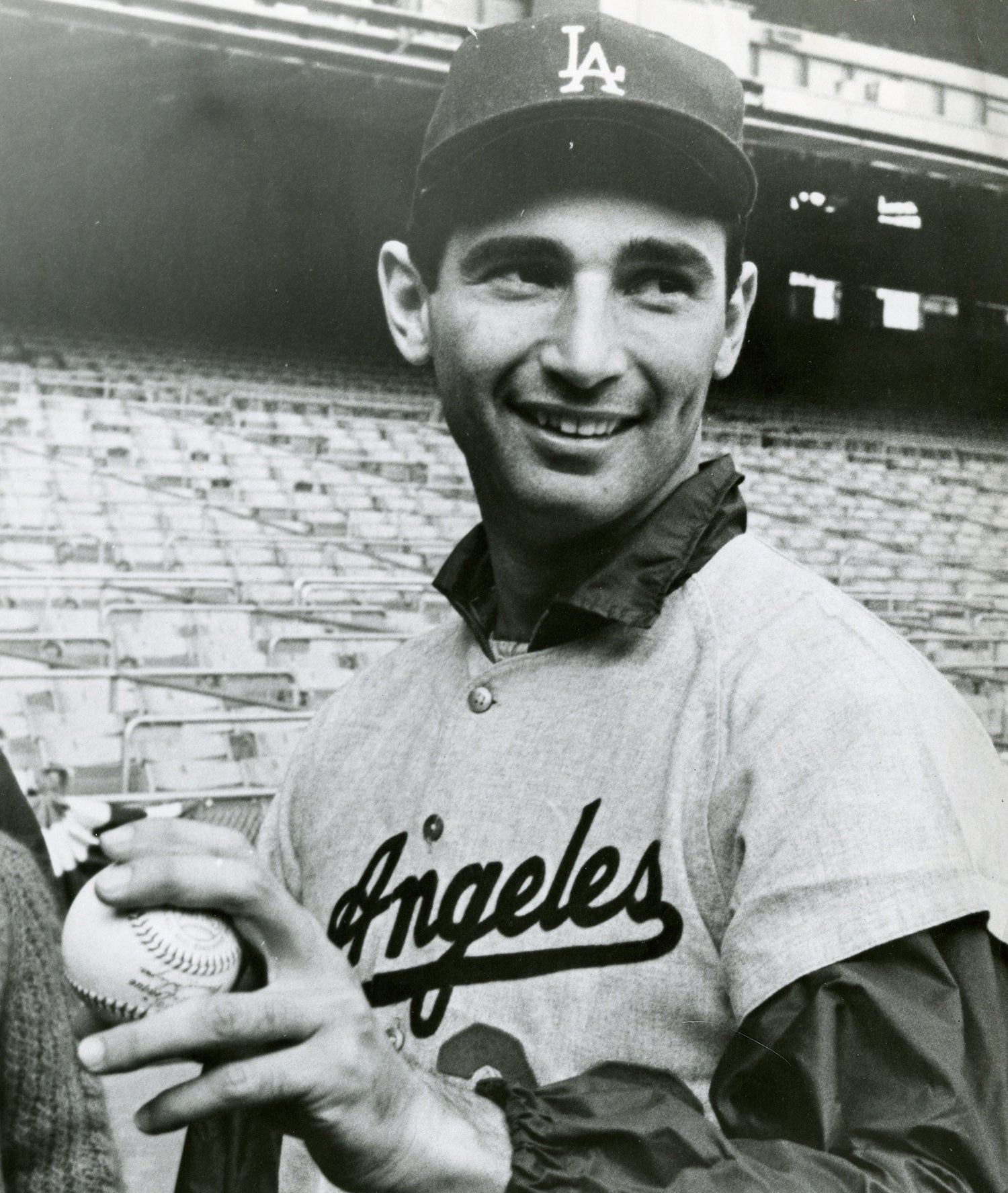

In today’s game, Richert might have been overlooked. As a high schooler, he was all of 5-foot-7, a lack of stature that can turn off the modern day scout. But in the late 1950s, height was not as hotly desired as it is now. At least three major league teams liked Richert enough to send scouts watch him play in the Connie Mack League located in the New York City area. The scouts for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Milwaukee Braves and New York Yankees all came away impressed with the left-hander’s high-octane fastball, a tangible toughness and a high level of character.

In 1958, the Dodgers’ scouting tandem of Al Campanis and Charlie Russo won the small bidding war for Richert, who was initially assigned to Reno of the Class C California League. In 200 innings, Richert struck out 215, but also walked 143. Clearly, he had the live arm that scouts of any era love, but the Dodgers realized that his control and mechanics needed some work.

In 1959, the Dodgers assigned Richert to the Three-I League, rated as Class B at the time. Richert improved his control, walking 99 batters in 156 innings while still striking out more than a batter an inning. He also lowered his ERA by more than a run, improving it to 3.29. Given such a performance, the Dodgers bumped him all the way up to the Double-A Southern Association in 1960, where he pitched for the minor league Atlanta Crackers.

Richert blossomed during his time in the Southern Association. He set a league record with 251 strikeouts, while also leading the league in wins, complete games and shutouts. Not surprisingly, Richert earned a promotion to Triple-A in 1961, but arm trouble knocked him out of action for the first six weeks of the season. He recovered to make 21 starts, but his ERA of 4.50 was higher than he would have liked.

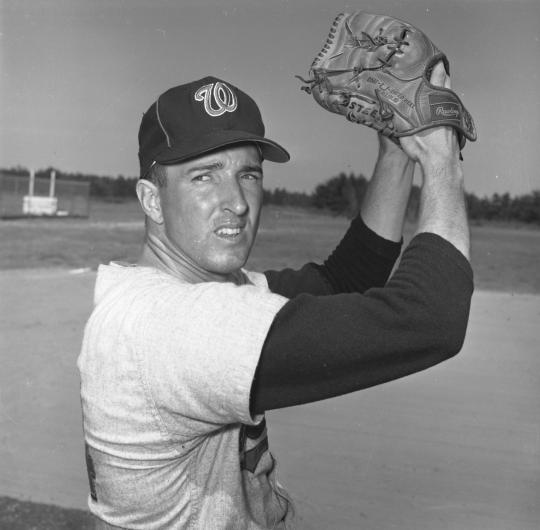

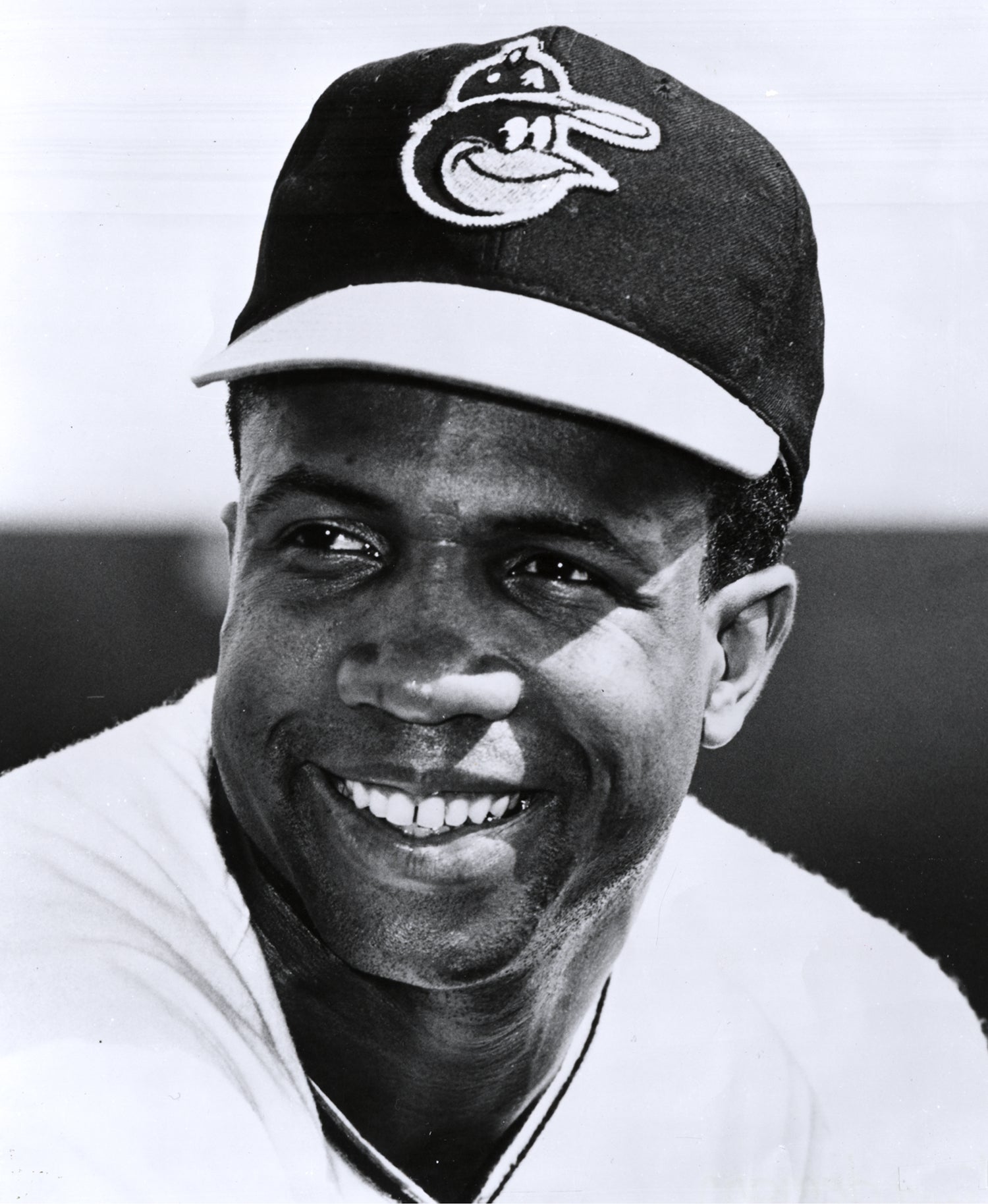

Still, the Dodgers decided to keep Richert on their Opening Day roster in 1962. By now, he had grown four inches, putting him at 5-foot-11. But no one really cared about that; they were far more interested in Richert’s explosive fastball. On April 12, Dodgers manager Walter Alston called on Richert to make his debut, a long relief outing against Cincinnati. Richert entered the game in the second inning – and proceeded to strike out the first six batters he faced. His victims included several brand-name players, notably Vada Pinson, Frank Robinson and Wally Post.

Richert’s debut included a four-strikeout oddity in the third inning, thanks to a passed ball that forced him to face an extra batter, whom he also struck out. By the end of his relief appearance, Richert had pitched three-and-a-third scoreless innings, striking out a total of seven while allowing no hits and no walks. Of his 40 pitches, he threw 33 strikes. And thanks to the Dodgers scoring seven runs in the fifth innings, Richert earned the victory.

As well as Richert pitched that day, he could not work his way into the Dodgers’ star-studded rotation, which included Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Johnny Podres and Stan Williams. After the brilliance of his first game, he began to struggle. By May, the Dodgers felt it best to send him back to Triple-A. Assigned to Omaha, Richert soon found himself facing uncertainty. One day he unleashed a fastball and felt something snap in his arm. It wasn’t a broken bone, but Richert clearly felt something change with his left arm and started to hold himself back in subsequent outings.

His manager, Danny Ozark, realized that Richert was uneasy about the condition of his arm. He told him to let loose, to throw as hard as he could, as a way of testing the arm. Richert did as told, and felt fine.

Richert pitched well at Omaha, earning another look from the Dodgers in August and September. Given a regular turn in the rotation, he did well down the stretch, as the Dodgers lost to the San Francisco Giants in a wild, three-game tiebreaker. Richert did not pitch in that series, which proved a crushing blow to the Dodgers’ season.

In 1963, Richert again split his time between Los Angeles and Triple-A ball. With the Dodgers, he served as a spot starter and long reliever, but was bypassed completely during the World Series. Still, he received a World Series ring, as the Dodgers swept the New York Yankees in four games.

The pattern of fragmented seasons continued in 1964. Richert dominated at Triple-A Spokane but mustered only mixed results with the Dodgers. The persistent inconsistency bothered the front office, but Richert’s age still made him a prospect. He was still only 24, young enough to find himself.

That winter, the Dodgers engaged the Senators in trade talks. The Dodgers wanted left-hander Claude Osteen, a promising sinkerballer coming off a 15-win season. The price tag for Osteen was steep. The Senators wanted slugging outfielder Frank Howard, third baseman Ken McMullen and Richert. On Dec. 4, the two sides agreed to the blockbuster deal.

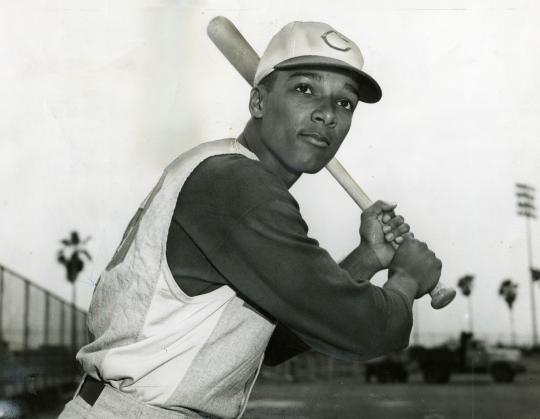

The trade would work out beautifully for Richert. Senators manager Gil Hodges made Richert a regular part of his rotation, where he initially struggled, and then placed him in the bullpen. Reinserted into the rotation later in the summer, Richert blossomed. He made 29 starts, won 15 games and spun an ERA of 2.60. The emerging left-hander not only made the All-Star team, but he also garnered some back-end support in the American League MVP voting.

Richert maintained his All-Star level of pitching in 1966. Though his ERA rose to 3.37, he still won 14 games while increasing his workload to a career best 245 innings. Richert again made the All-Star team and again received MVP consideration.

As he entered his age 27 season in 1967, the Senators had every reason to believe that Richert would continue to serve as a bellwether of their staff. Hodges loved him, regarding him as one of the top left-handers in the league and putting him in the same lofty category as the more heralded Sam McDowell. All seemed well with Richert and the Senators.

But the first few weeks of the new season did not go as planned. Richert lost six of his first eight decisions, while his ERA rose to 4.64. Perhaps reacting too quickly to the early season slump, the Senators decided that the time was right to make a trade. They sent Richert to the Baltimore Orioles for slugging first baseman Mike Epstein. Just like that, after two All-Star Game appearances in two years, Richert was moving across the Beltway to Baltimore.

The Orioles added Richert to a young rotation that featured Tom Phoebus, Dave McNally and Jim Hardin. Richert’s record of 7-10 with Baltimore would tell only a small part of the story; his ERA of 2.99 and a paltry total of 107 hits in 132 innings provided a far better indication of his value to the Orioles.

With a preponderance of starting pitching in 1968, the Orioles made Richert a full-time reliever in 1968. The season started in tumultuous fashion across the major leagues, delayed by the assassination of Martin Luther King in Memphis. With rioting breaking out in several pockets throughout the country, Richert was called into service. A member of the D.C. National Guard, Richert saw active duty for the first time. He and his former teammate, Senators shortstop Eddie Brinkman, both saw the start to their season delayed. Serving a 12-day stint, Richert patrolled the streets of D.C and offered protection to firemen as they dealt with fires stemming from the riots.

Richert’s involvement with the National Guard stemmed in part from his experiences working with wounded members of the military. In a lengthy interview with writer and author Doug Wilson, Richert explained his initial connection to the military.

“Playing in Washington, we were close to Walter Reed Army Hospital and I ended up doing a lot of work with wounded soldiers,” Richert told Wilson. “I always thought that was important. I got involved with a group of seven or eight officers who had been shot up and lost limbs… They had a certain ward there, Ward One. They were all Green Berets, the Special Forces.

"They were really impressive guys; very smart, very dedicated. We would sit around and talk and later they would come over to my apartment and we would do things together... They were special guys. Their attitudes were just amazing. Here they were, severely wounded, some had lost arms or legs, and yet every one of them said they would go back (to war) in a heartbeat."

As a result of his initial contact with the soldiers at Walter Reed, Richert set up a special program. He arranged for opposing players in town to play the Senators to travel to the hospital, talk to the soldiers and try to boost their morale. The Associated Press caught wind of the program and named it the VIP Program – for Very Important Patients.

It’s impossible to know whether Richert’s two-week National Guard deployment affected his pitching in 1968, but it’s a question work asking. By his own admission, Richert became more serious and solemn in his approach, and less inclined to crack jokes in the clubhouse. On the surface, his 3.47 ERA looked decent enough, but that was actually well below league-average in the Year of the Pitcher.

It may have been caused in part by his stint in the National Guard, or simply a reflection on the adjustment Richert faced in moving from the starting rotation to the bullpen; prior to 1968, the left-hander had made fewer than two dozen relief appearances in his career. After a wintertime visit to see American soldiers in Vietnam, Richert returned to the Orioles for a second season – and saw his situation stabilize.

Pitching in a highly specialized relief role, in which he logged only 57 innings in 44 appearances, Richert dominated opposing hitters. He struck out 54 batters in 57 innings and lowered his ERA to 2.20. Becoming a key part of a deep bullpen, Richert did his small, subtle part in helping the Orioles run away with the newly formed American League East.

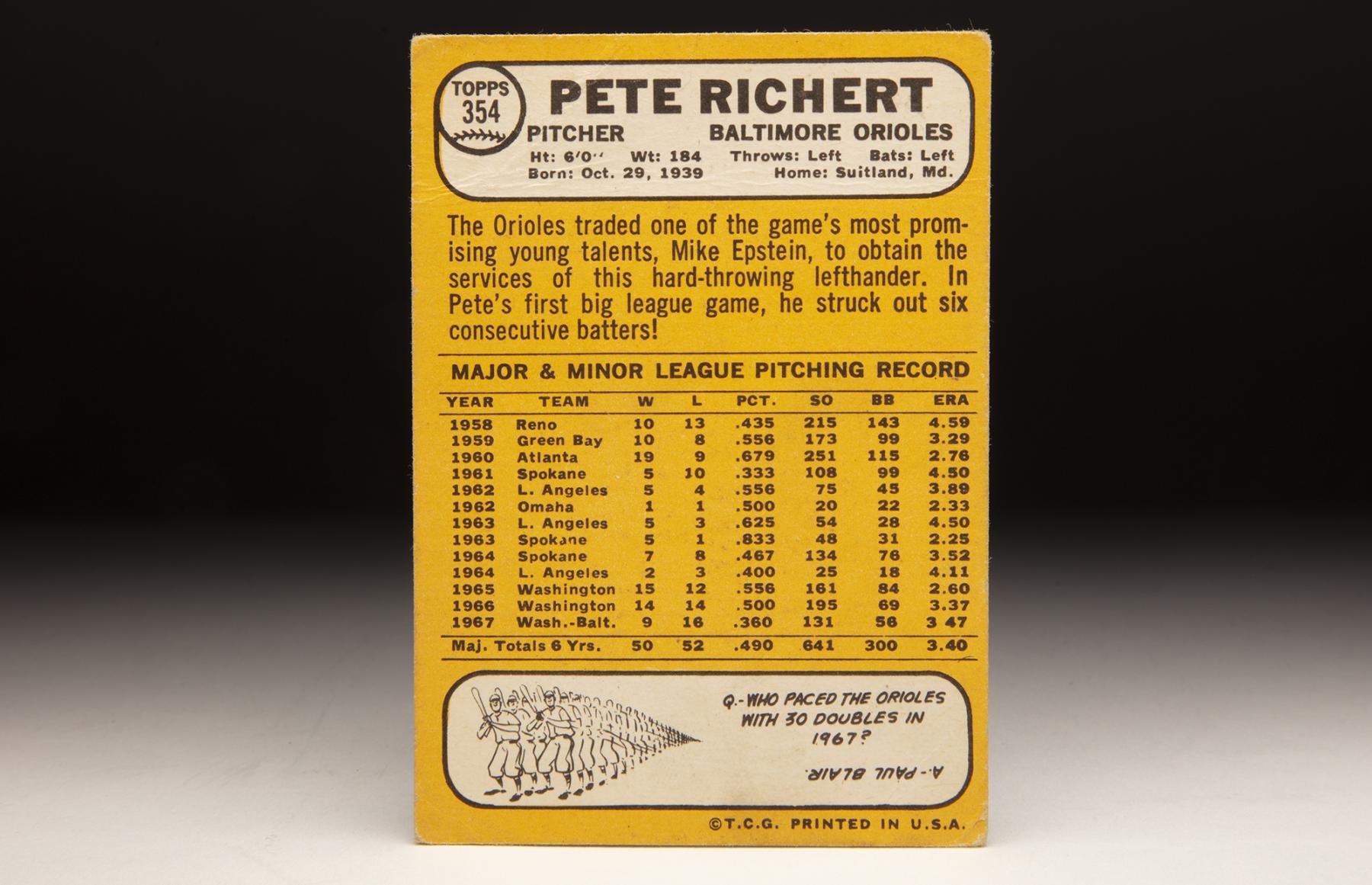

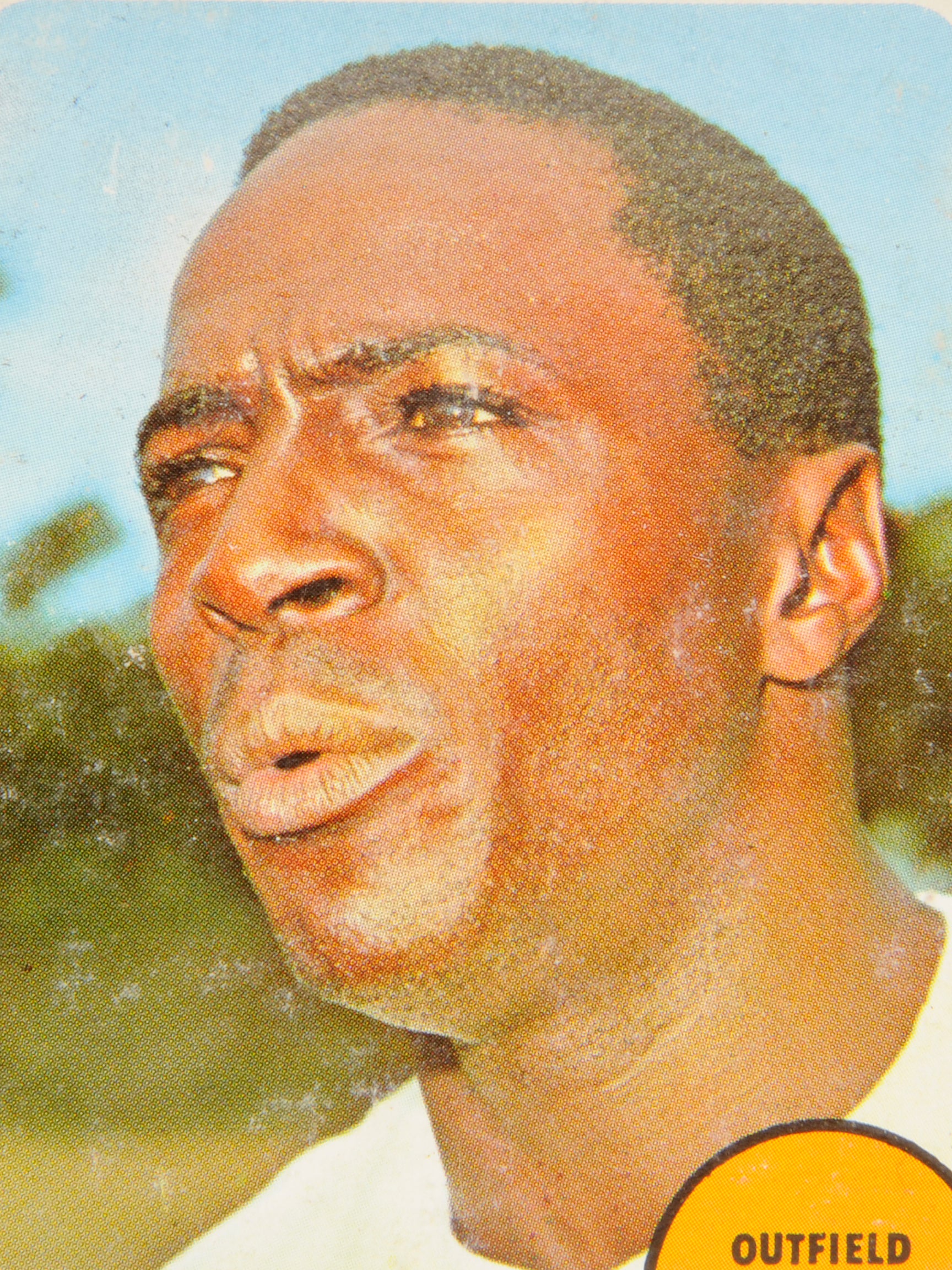

As well as Richert pitched during the regular season, his moment of fame came during the World Series. In Game 4, the Orioles and New York Mets played into the bottom of the 10th, when the Mets put their first two runners on base against reliever Dick Hall. Orioles manager Earl Weaver then called on Richert to face pinch-hitter J.C. Martin, who laid down a well-placed bunt along the first base line. Richert fielded the ball cleanly with his bare hand and fired to first, but the low throw hit Martin on his wrist and rolled away from second baseman Davey Johnson, allowing Rod Gaspar to score the winning run.

Replays showed that Martin was running inside of the baseline and should have been called out for interference. But home plate umpire Shag Crawford didn’t see it that way; the Orioles put up little protest, Richert was charged with an undeserved error, and the Mets now had a commanding lead of three games to one in the Series.

One day later, the Orioles lost the Series. That disappointment would soon give way to a season of complete triumph in 1970.

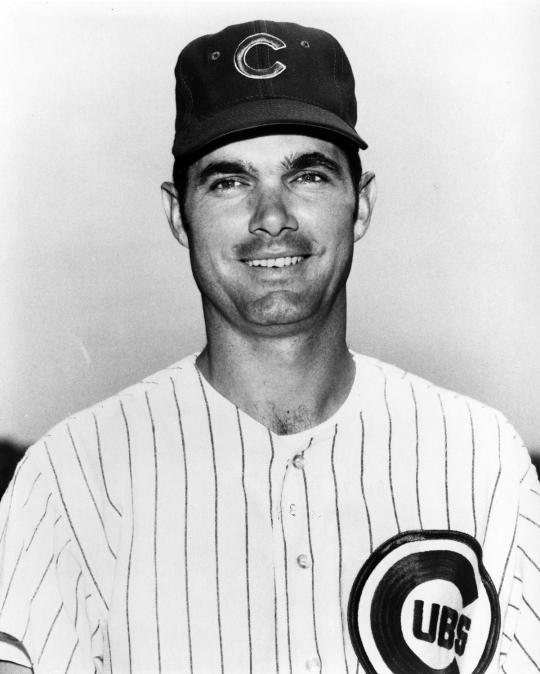

In Game 4 of the 1969 World Series, J.C. Martin of the Mets (pictured above in a Cubs uniform) brought home the winning run when a throw from Pete Richert on a bunt hit Martin in the wrist, allowing Rod Gaspar to score. The Mets won the World Series the following day. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Richert delivered the best season of his career: a 1.98 ERA over 50 games, a record of 7-2, 13 saves and 66 strikeouts in 54 innings. Richert emerged as the team’s best reliever, just as the Orioles emerged as the game’s top team. After steamrolling the American League East and sweeping Minnesota in the ALCS, the Orioles dismantled Cincinnati in the World Series. Richert made one appearance, notching a save in Game 1.

The 1970 campaign turned out to be Richert’s last hallmark season. His performance fell off considerably, with his ERA rising to 3.47. Still, the Orioles won their third straight pennant, giving Richert a chance to make another scoreless appearance in the World Series. Much like 1969, the Orioles found themselves upset by an underdog team of overachievers, this time the Pittsburgh Pirates.

The 1971 World Series marked the end of Richert’s time in Baltimore. That winter, the Orioles pulled off a blockbuster trade with the Dodgers, sending Richert, who was now 32, and Frank Robinson to LA for a package of young prospects, headlined by promising right-hander Doyle Alexander. For the second time in his career, Richert became a Dodger.

Over the next two seasons, Richert pitched effectively as a middle man out of Walt Alston’s bullpen. Needing some help with their offense, the pitching-rich Dodgers traded Richert to St. Louis at the 1973 Winter Meetings, in a straight up deal for veteran outfielder Tommie Agee. In 13 games with LA, Richert posted an ERA of 2.38, but his control had abandoned him; he walked 11 batters in 11 innings. In late June, the Cardinals sold him to Philadelphia, where he pitched effectively over 21 games, but came down with a bad elbow, ending his season early. Richert never pitched again.

A late-season examination showed why he had elbow pain: a clot in his pitching arm, which required surgery. The medical condition convinced Richert that it was time to retire. That October, Richert did some broadcast work during the World Series but then left baseball to start an organization called Athletes for Youth, which counseled youngsters against the perils of drug abuse. As part of his organization’s work, Richert regularly spoke to drug addicts and visited methadone centers. Given his work with military veterans, none of Richert’s efforts to help those affected by drug abuse should have come as a surprise.

In 1989, Richert returned to the game as a minor league pitching coach. He worked almost exclusively on the West Coast, allowing him to stay close to his family in Rancho Mirage. In 2001, Richert left the game for good, beginning a life of retirement in Southern California. Even in his early 80s, he continues to spend much of his time playing golf near his home.

For so many years, Richert has been remembered mostly for his remarkable major league debut and for the infamous J.C. Martin play in the World Series. Card collectors have also had fun with Richert’s weirdly spiked hair, so evident on his 1968 Topps card. But those stories give us little insight into Richert’s real character and legacy. He deserves to be remembered far more for his selfless work with wounded warriors and those plagued by the ills of drug abuse. The man with the bad hair is truly one of the game’s good guys.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame