- Home

- Our Stories

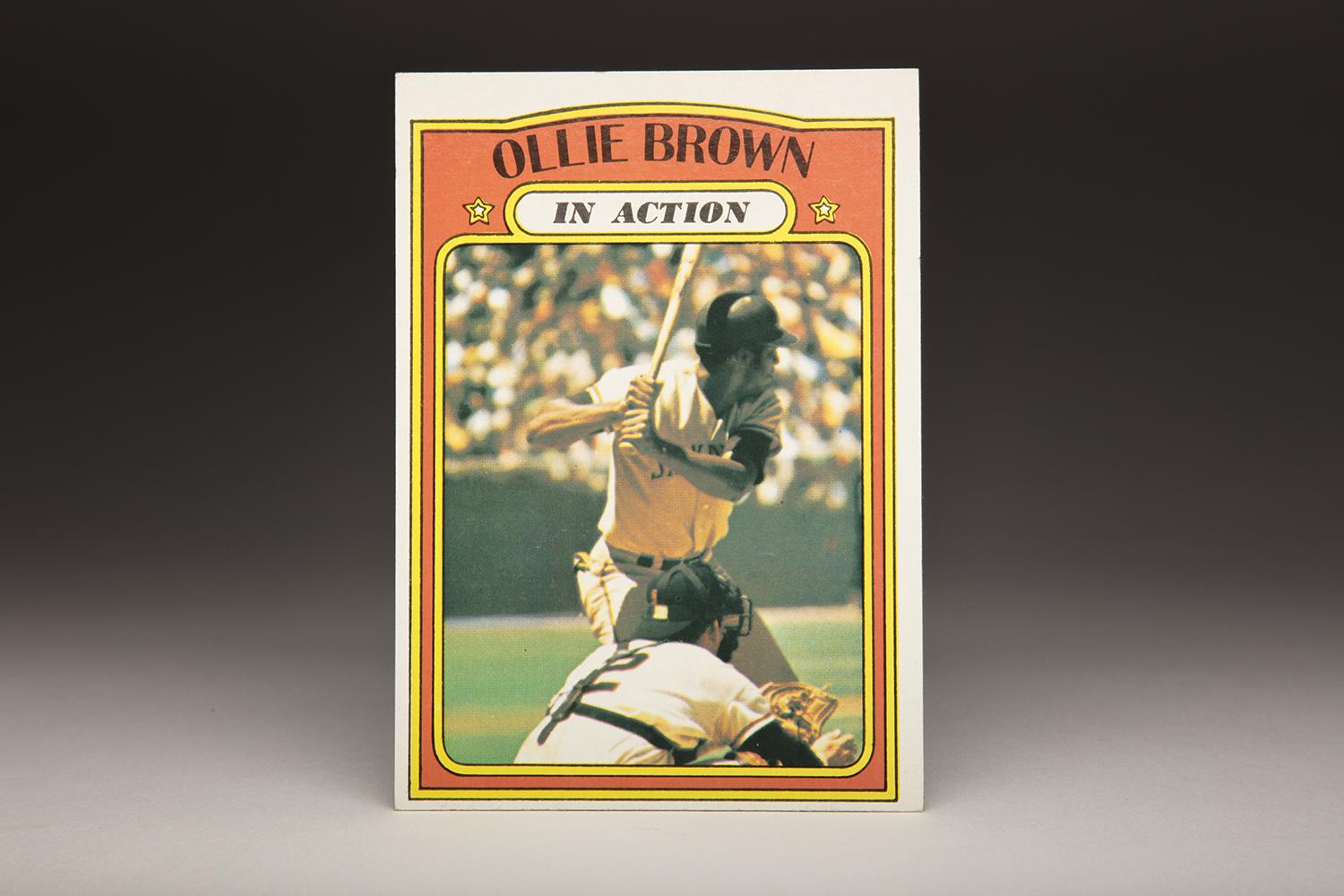

- #CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ollie Brown

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Ollie Brown

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Not only did I start collecting baseball cards during the spring and summer of 1972, but I became particularly captivated by the series of cards that Topps highlighted as “In Action” cards. As someone who was new to the hobby, I just assumed that Topps had always included action cards in its sets, but I soon discovered that this was not the case. In the 1960s, Topps had included colorized action shots of black-and-white photographs on its World Series cards. But these were clearly airbrushed and colorized, and these action shots were never featured on the standard cards.

The first examples of true action shots for individual players did not happen until 1971, when Topps included action photographs for 52 players. These action shots became such a hit with young collectors that Topps realized it had created something wonderful, something that needed to be highlighted with its next set. So in 1972, Topps included a number of action cards, increasing the total to 72, but this time the company highlighted the cards with a bright red frame and the words “In Action” emphasized near the top of the card.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As kids, we absolutely loved these cards, even if we didn’t realize that they also represented a new trend in the hobby. Among my most favorite of the 1972 “In Action” shots is the card of “Downtown” Ollie Brown. Ever since I first saw this card, I became fascinated with the lighting in the photo. It’s as if the photographer pointed a spotlight onto the left side of Brown’s body and onto the catcher while taking this shot at San Francisco’s Candlestick. Or perhaps the cameraman did something unusual with the exposure. Whatever the case, the lighting creates a contrast with the shadows on the right side of the photograph. The effect is almost surreal. In a way, Brown and his catcher appear to be spotlighted on a well-lit stage as they stand in the midst of a ballpark that is already bathed in bright sunlight.

The camera angle also give us an interesting view of Brown and the catcher, Dick Dietz of the San Francisco Giants. Brown and Dietz appear to be so close together that one could imagine Brown swinging at a pitch and smacking the veteran Giants catcher in the left shoulder. Of course, that didn’t happen here – that would have been catcher’s interference on Dietz – but the image creates the illusion of the batter and catcher coming into conflict with each other. Still, it is remarkable how close the two players are to each other; while the pitcher is 60 feet, six inches away, the batter and catcher are always breathing down each other’s necks.

I got to thinking about Brown last week, when former major leaguer Rick Ankiel came to the Hall of Fame to discuss his new book, The Phenomenon. Like Ankiel, Brown was a player who pitched early in his career, but switched to the outfield because of extreme wildness.

Additionally, Ankiel had one of the strongest outfield arms in recent memory. Ankiel threw with such arm strength that some old-time baseball people began to compare him to other great outfield arms of the past, players like Roberto Clemente and Rocky Colavito and Ellis Valentine. And of course, Ollie Brown. When it came to throwing a baseball from the outfield depths to home plate, few could do it like Brown.

Some experts placed Brown at the top of the list. In a late 1970s interview with the Associated Press, famed Cincinnati Reds superscout Ray Shore was asked to rate the finest outfield throwing arm he had ever seen. With little hesitation, Shore offered up his answer.

“The best I’ve ever seen is Ollie Brown,” Shore told the AP. “There’s one throw he made that I never could believe. Tie game, 0-0, the Cubs and San Diego. There’s a fly ball to right-center and Brown goes over. He waves off the center fielder, makes the catch going toward center, turns, and throws the ball to the plate. Belly button high on a fly it goes. Right there to the catcher. Greatest throw I’ve ever seen.”

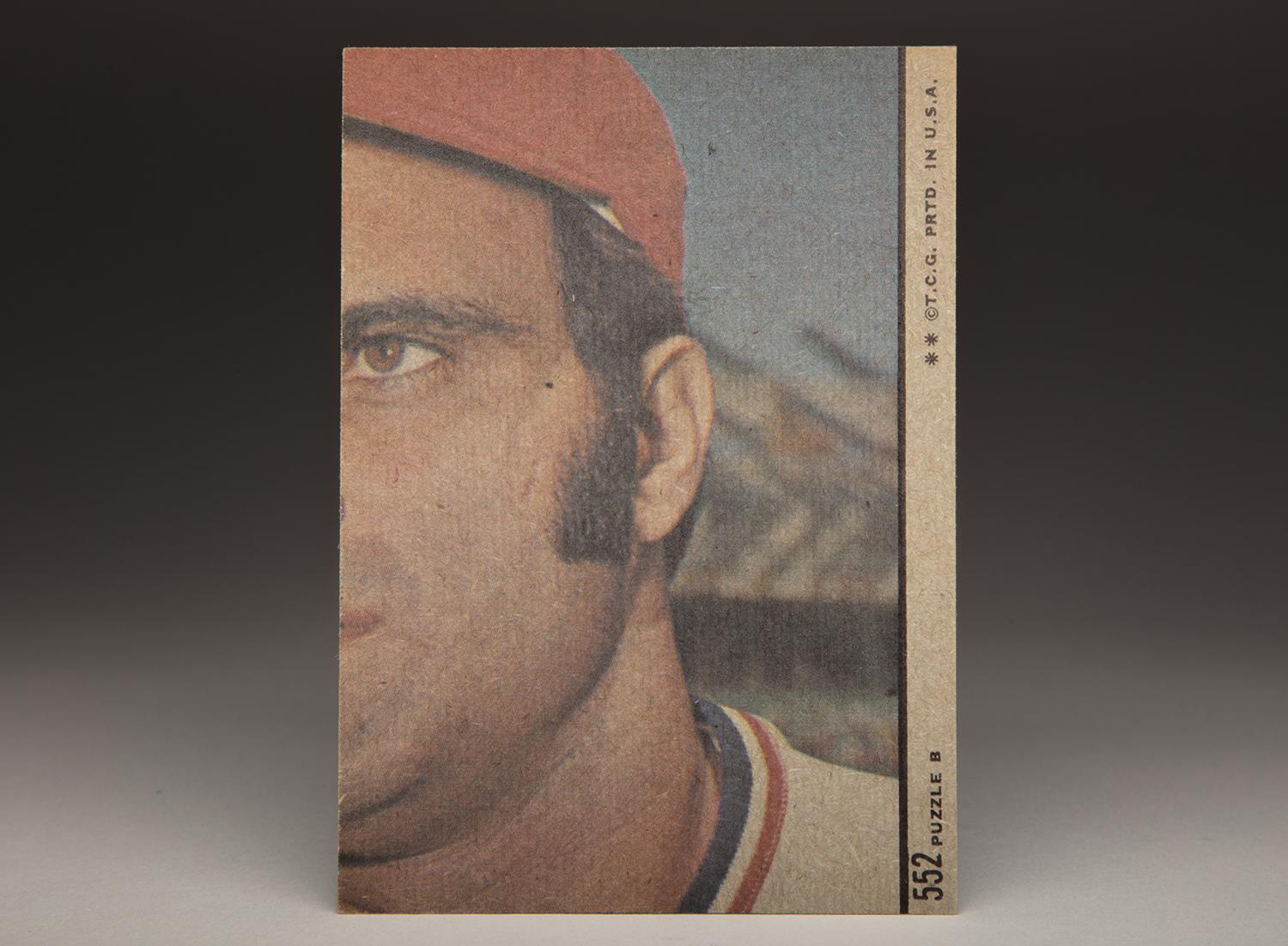

The reverse side of Ollie Brown's 1972 Topps card features a puzzle piece of then-Cardinals catcher Joe Torre. Certain cards within the 1972 Topps set had partial pictures on their reverse sides, which made a complete image when combined. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Other scouts, while less bullish than Shore, rated Brown’s arm as the equal of Clemente’s. On a more conservative scale, it is probably safe to say that Brown possessed one of the five to 10 greatest outfield throwing arms in history.

Prior to games, Brown put on a show for fans who enjoyed watching players with extreme arm strength. As he stood deep in the right field corner, Brown would proceed to throw the ball to third base – on a fly. He did this time after time. If only Topps had captured a picture of Brown throwing a baseball, that would have been even better than the action card the company produced in 1972.

Brown’s story is one that has long fascinated me. To begin with, he came from a remarkably athletic family. His younger brother, an outfielder named Oscar, played for the Atlanta Braves in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Another brother, Willie, was a standout football player at Southern California before becoming a pro running back with the Los Angeles Rams and Philadelphia Eagles.

Ollie Brown’s baseball journey began with the Giants, the team that he was playing against on his 1972 card. The Giants originally signed him as an amateur outfielder in 1962, but made him a pitcher in ‘63. Brown featured a good, live fastball, but he was so wild that he could have challenged Steve Dalkowski to a bases-on-balls contest. In 1963, Brown walked 132 batters in 123 innings. He also led his league with 24 wild pitches.

Realizing that a change was needed, the organization soon moved Brown back to the outfield. That way, the Giants felt that his strong arm would remain an asset, while also creating an opportunity for his full offensive potential to be tapped.

By 1964, it was clear that Brown belonged in the lineup every day as an outfielder. Playing for the Class A Fresno Giants of the California League, Brown put up monstrous offensive numbers, including 40 home runs, a .671 slugging percentage, and a .329 batting average – good enough to earn him league MVP honors. Of those 40 home runs, several traveled toward dead center field in Fresno. That happened to be in the general direction of downtown Fresno. So naturally, in delivering the play-by-play, Fresno’s radio announcer referred to the ball heading “downtown.” With that, the wonderful nickname of “Downtown” Brown was born. Later on, people in the game added “Ollie” to the nickname: Downtown Ollie Brown. It sounded so good that radio and TV announcers felt compelled to state the nickname at least once per game.

Brown’s MVP performance in Fresno catapulted him all the way to Triple-A the following spring. He moved up to Tacoma, the Giants’ affiliate in the hitter-friendly Pacific Coast League. Brown again put up big numbers, hitting 27 home runs and earning his first call-up to the major leagues.

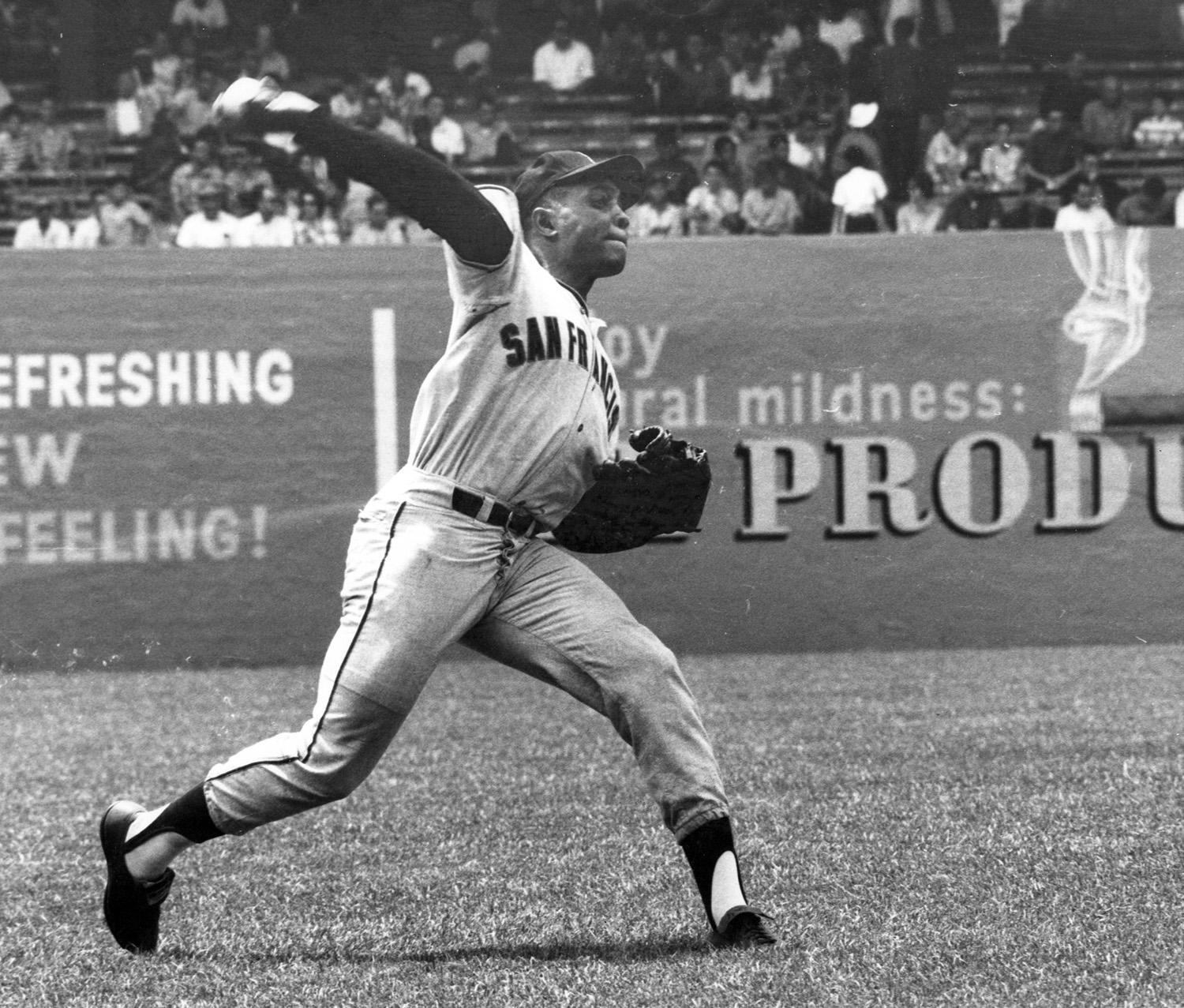

The Giants had high hopes for Brown, who had the kind of tall, lean build that scouts preferred in an outfielder. With his combination of power and footspeed, some talent evaluators compared him to a young Willie Mays. By 1966, Brown was deemed ready for his first fulltime gig in the major leagues. He would spend most of 1966 in San Francisco, but he struggled, hitting only .233 with seven home runs in 115 games. To complicate matters, the Giants had a crowded outfield, which already featured the real Willie Mays, a young Jesus Alou, and a top-tier prospect in switch-hitting Ken Henderson.

Despite the stiff competition, Brown moved up in the pecking order in 1967. Henderson fell into an early season slump and lost the right field job to Brown, who responded by hitting a respectable .267 with 13 home runs in 120 games. He played well, despite being hit in the face with a pitch by Houston’s Claude Raymond. Once again, Brown seemed on the verge of a breakthrough. Then came the reality check of 1968. Brown slumped badly enough to lose his starting spot in the outfield and earn a demotion to Triple-A Phoenix.

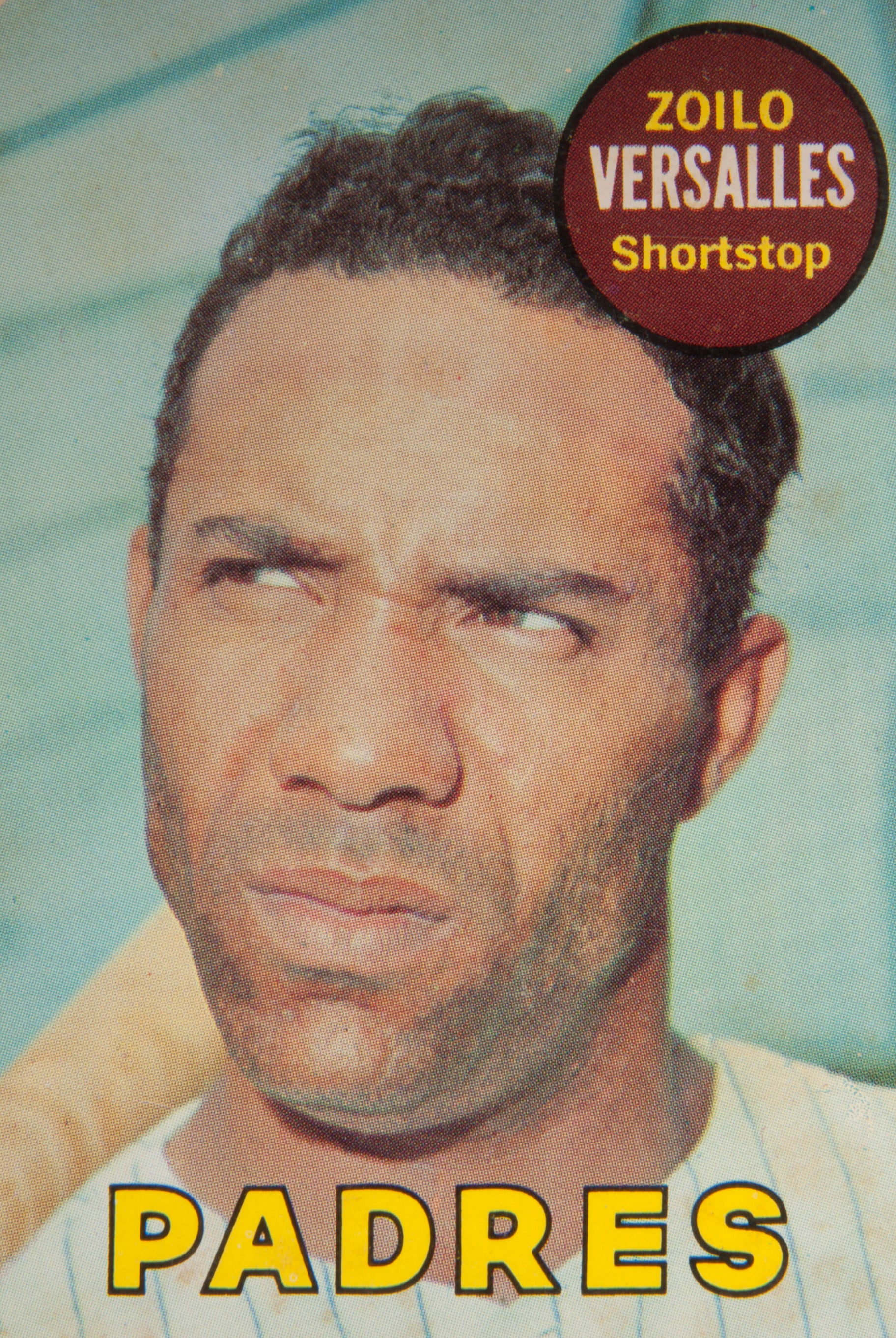

Brown compounded matters by refusing to report immediately to Phoenix. The Giants responded by suspending him briefly, before he finally changed his mind and agreed to report. Given such an indiscretion, along with his inconsistent hitting, it didn’t take long for Brown’s status to change quickly from untouchable to moveable. The Giants left Brown unprotected in the 1968 expansion draft and watched the Padres take him with the first pick. For many within the organization, the selection of Brown was a disappointing closing chapter; after all, the Giants had once considered the 24-year-old a superstar-in-the-making.

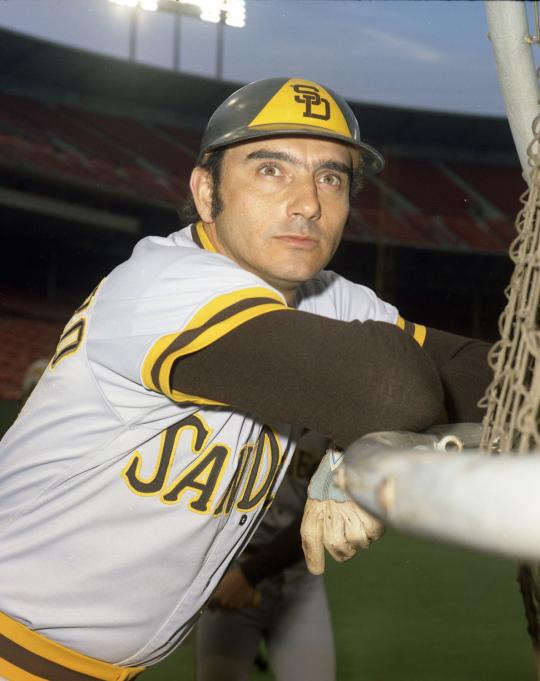

As their first pick in the expansion draft, Brown became the original Padre. The new franchise expected him to become the cornerstone to the team, a slugger who could anchor the middle of the lineup while providing good defense in right field. Although Brown did not meet all of the expectations, he hardly flopped in his first full season with San Diego. Brown hit 20 home runs, stole 10 bases, and played a solid right field, where he threw out 14 baserunners who foolishly tried to advance against him. Although he was quiet and soft spoken, he became exceedingly popular with fans at San Diego Stadium, who cheered him more than just about any player on the team.

Now more comfortable in his new environs, Brown blossomed in his second year with the Padres. He batted .292, posted a slugging percentage of .489, and pushed his OPS above .800. The numbers were very good across the board, but became more impressive given the reputation of San Diego Stadium as a pitcher’s park. Defensively, Brown regressed somewhat in right field, where he committed 10 errors, but he also threw out 12 baserunners. All in all, the Padres considered him a player on the verge of stardom.

At 26 years old, Brown seemed on the cusp of greatness. Then came the regression. In 1971, he slumped badly, his home runs falling off from 23 to nine. Brown became pull-happy. He tried to hit everything to left field, making him vulnerable to outside pitches, particularly breaking balls. He also became too aggressive at the plate, swinging at pitches that were not strikes. To compound the situation, Brown developed a habit of not hustling at all times, perhaps a by-product of his slumping fortunes at the plate.

When Brown reported to Spring Training in 1972, he made an admission that is rare for a player. “I know there were times last year when I didn’t give 100 percent,” a brutally honest Brown told San Diego sportswriter Phil Collier. Brown vowed to change his effort level in ’72. “I want to play in every game this year, if that’s possible, and I want to play as hard as I can… It has taken me this long to mature. I wish it had happened sooner.”

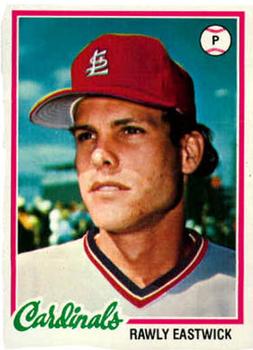

Brown played hard in April and May, but didn’t play well. After a bad start to the new season, the Padres ran out of patience. In mid-May, before his Topps action card had even come out, they announced a major trade with the Oakland A’s. The deal sent Brown to Oakland for a package of backup catcher Curt Blefary, left-hander Mike Kilkenny and a player to be named later. For the A’s, the trade represented something of a coup. A’s owner and general manager Charlie Finley had long admired the talents of Brown. In fact, at one point, the A’s had offered the Padres four players and a $200,000 for Brown, only to have the trade turned down. In making the current trade, Finley had acquired Brown at a bargain basement price – while also making his Topps card out of date.

The A’s already had a first-class right fielder in Reggie Jackson, but they planned to move him to center, clearing Brown to move into right field. In Jackson and Brown, the A’s now had two of the game’s strongest throwing arms playing next to each other in the same outfield. On the surface, the plan sounded good, but Brown did not play well for the A’s. In 60 plate appearances, he hit only one home run, showing little of the power that the Giants and Padres had once seen.

Not much for patience, Finley gave up on Brown. At the end of June, he sold Brown on waivers to the Milwaukee Brewers. At least that’s how the deal was announced. Secretly, the Brewers agreed to send the A’s the rights to outfielder Billy Conigliaro, who had retired after the 1971 season.

Brown rekindled his career in Milwaukee, hitting a respectable .279 in a platoon role, but without the power of his prime seasons. At one point, the Brewers tried Brown at third base, but that move negated the greatest strength to his game: His throwing arm. After the 1973 season, the Brewers decided to include him in a nine-player deal with the California Angels. Brown returned to the West Coast, in a deal that brought center fielder Ken Berry and left-handers Clyde Wright and Steve Barber to Milwaukee.

As it turned out, Brown never appeared in a regular season game for the Angels, despite appearing on a 1974 Topps card wearing airbrushed California colors. During the latter days of Spring Training in 1974, the Angels sold him to the Houston Astros, a team that desperately needed power. The transaction also reunited Brown with Preston Gomez, his former manager in San Diego.

Brown turned out to be a poor fit for the Astros, who played their game in the cavernous Astrodome, not suited for free-swinging sluggers. After 27 games, the Astros moved on from Brown, sending him to the Philadelphia Phillies in a waiver sale transaction. At first, the Astros announced that they would receive a player in return for Brown, but they eventually settled for cash-only compensation.

At 30 years old, and after mostly failed stints in Houston and Oakland, and only mediocre success in Milwaukee, most scouts would have given up on Brown ever being a contributor again. One more release figured to signal the end of Brown’s playing days. Clearly at the crossroads, Brown set about changing the course of his career. With the Phillies, he accepted being a bench player. Manager Danny Ozark started him occasionally against left-handed pitchers, while also using him as a pinch-hitter and late inning defensive replacement.

In 1975, Brown rekindled his career as one of the game’s best bench players. Platooning at times with Jay Johnstone in right field, Brown accumulated only 161 plate appearances, but made the most of them, batting .303 and posting a career-high OPS of .879. Brown became the leader of one of the National League’s best bench brigades, joining forces with backup catchers Johnny Oates and Tim McCarver, backup first baseman Tommy Hutton, and veteran utility infielder Tony Taylor.

Brown remained an effective bench player through 1976, when he played a role in the Phillies’ successful run at the National League East title. His hitting then fell by the wayside in 1977, as his batting average dipped to .254, but he once again had the chance to play in the Postseason. Now a free agent, the 33-year-old Brown drew little interest on the wintertime market. He decided to retire, calling it quits after a 13-year career.

After leaving the game as a player, Brown chose to stay out of baseball, instead returning to Southern California and becoming, in his words, a “semi-retired businessman.” He remained a lifelong fan of the game and an avid watcher of baseball on TV. Unlike many retired players from earlier generations, he also expressed admiration for modern day players, praising them for their ability to stay in shape all year round.

Brown remained in California for the rest of his life. In 2014, he was diagnosed with mesothelioma. A year later, at the age of 71, he succumbed to complications from the disease.

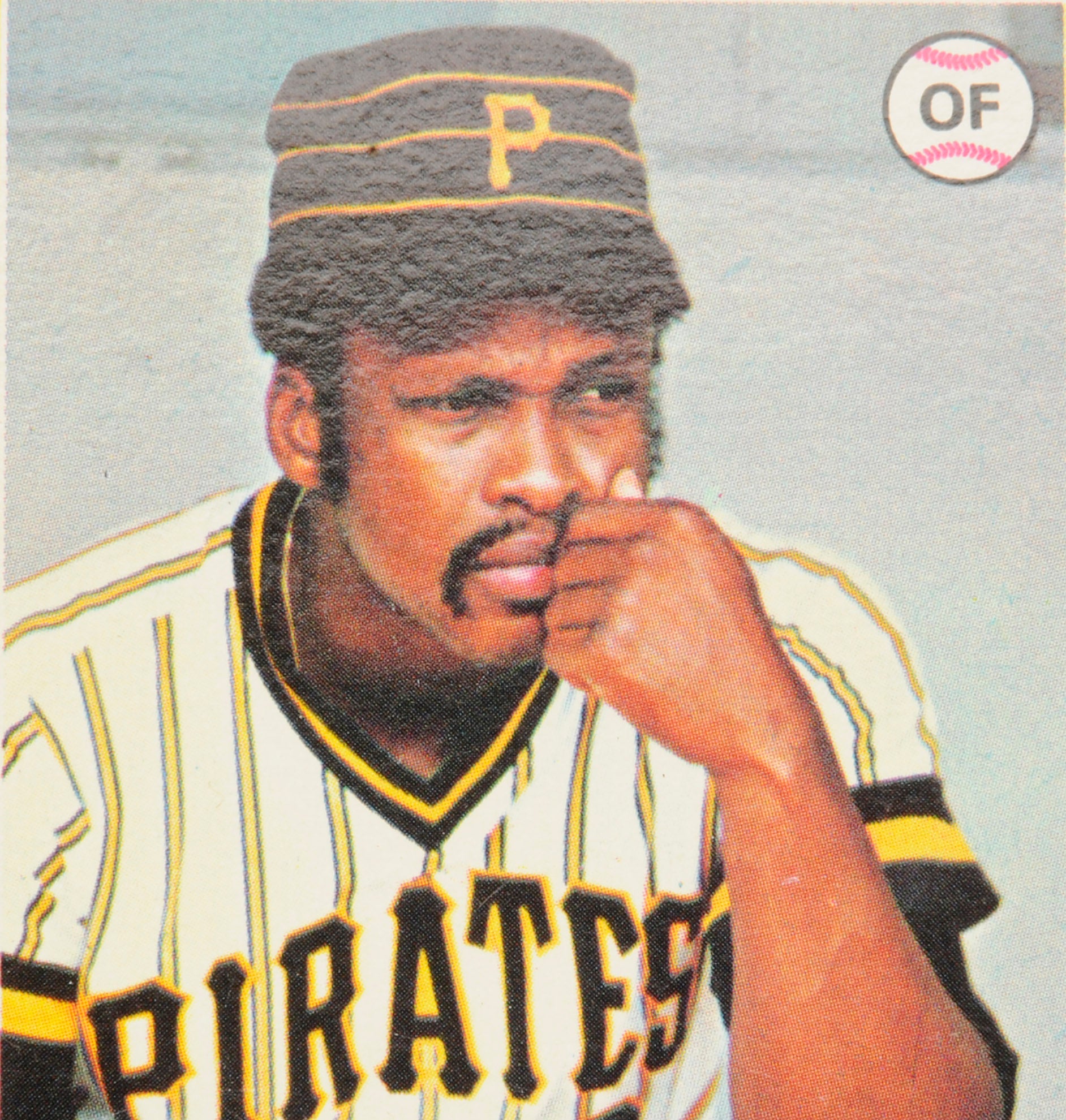

When Ollie Brown was called up to the big leagues full-time in 1966, the San Francisco Giants already had a crowded outfield, including Willie Mays, Ken Henderson and Jesus Alou (pictured above). (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

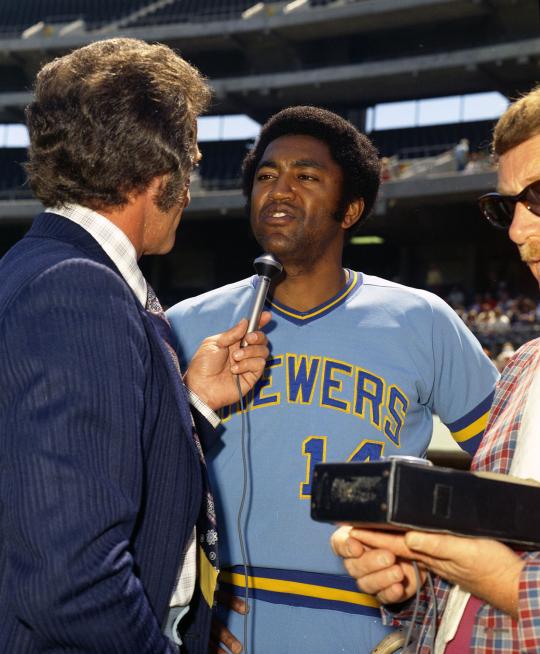

Padres catcher Chris Cannizzaro said his teammate Ollie Brown was a respected member of the Padres’ clubhouse. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

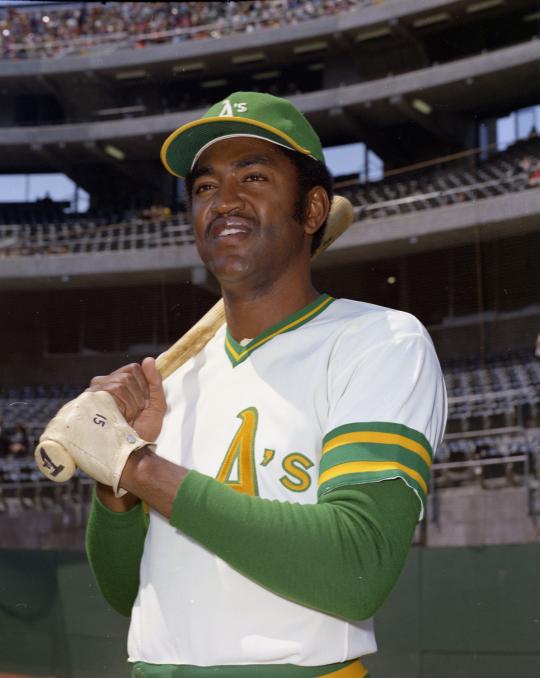

Ollie Brown played for three teams during the 1972 season, including the Oakland Athletics. (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

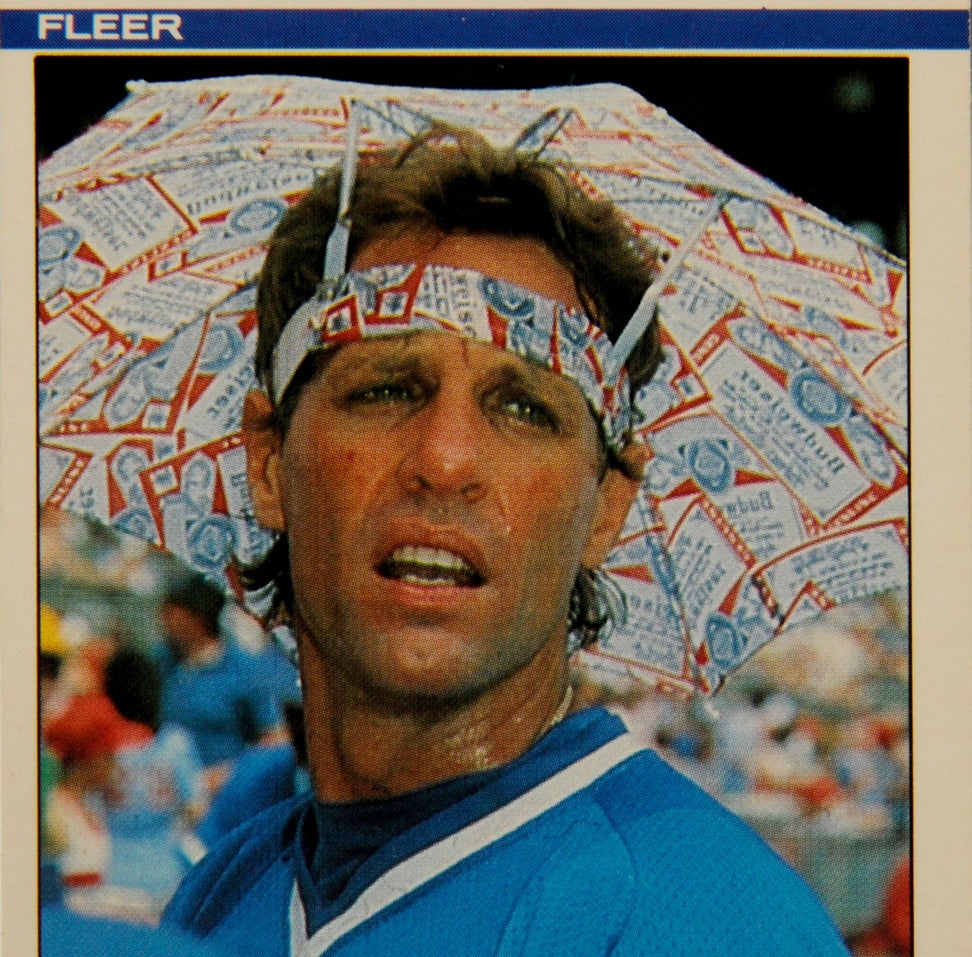

Reggie Jackson was playing right field when Ollie Brown was traded to the Athletics, but after the trade Jackson was moved to center so Brown could play right. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Brown’s death drew a reaction from some of his former teammates, who recalled him as one of the game’s good guys. “He was one of the better people I played baseball with,” former Padres catcher Chris Cannizzaro told the Los Angeles Times. “He was quiet, did his job, played hard and he was just a good person.”

Like Cannizzaro, I have good recollections of Brown, but for different reasons. I never had the chance to meet him, but his baseball cards always stir favorable memories, from that powerhouse throwing arm to that wonderful nickname. Just saying the name, Downtown Ollie Brown, makes a baseball fan feel good.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum