- Home

- Our Stories

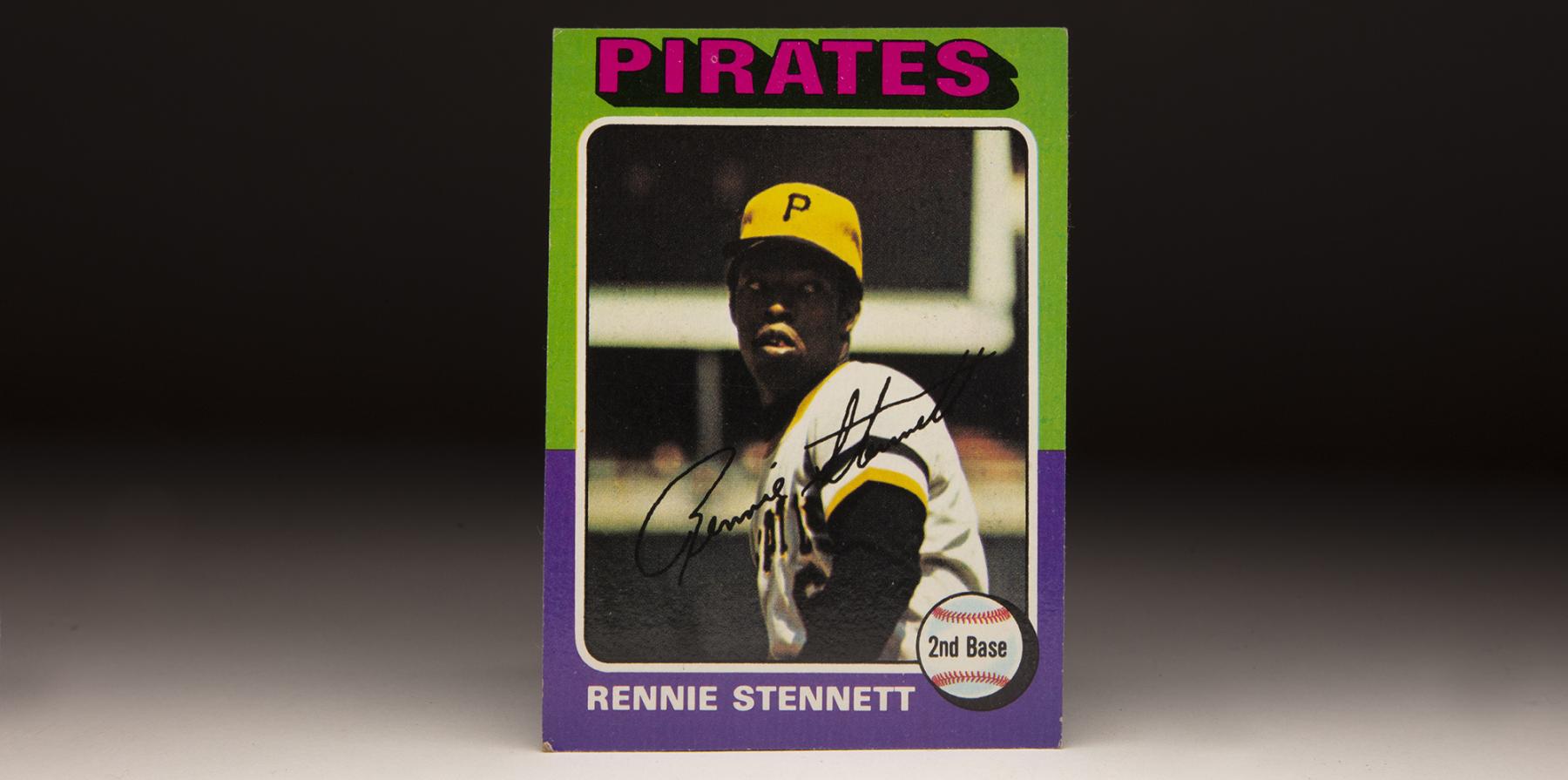

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Rennie Stennett

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Rennie Stennett

The photo ran in newspapers around the country on Aug. 22, 1977: Pirates second baseman Rennie Stennett, flat on his back on a stretcher, looking dejectedly at the photographer as teammates, including Jim Fregosi, carried him off the field.

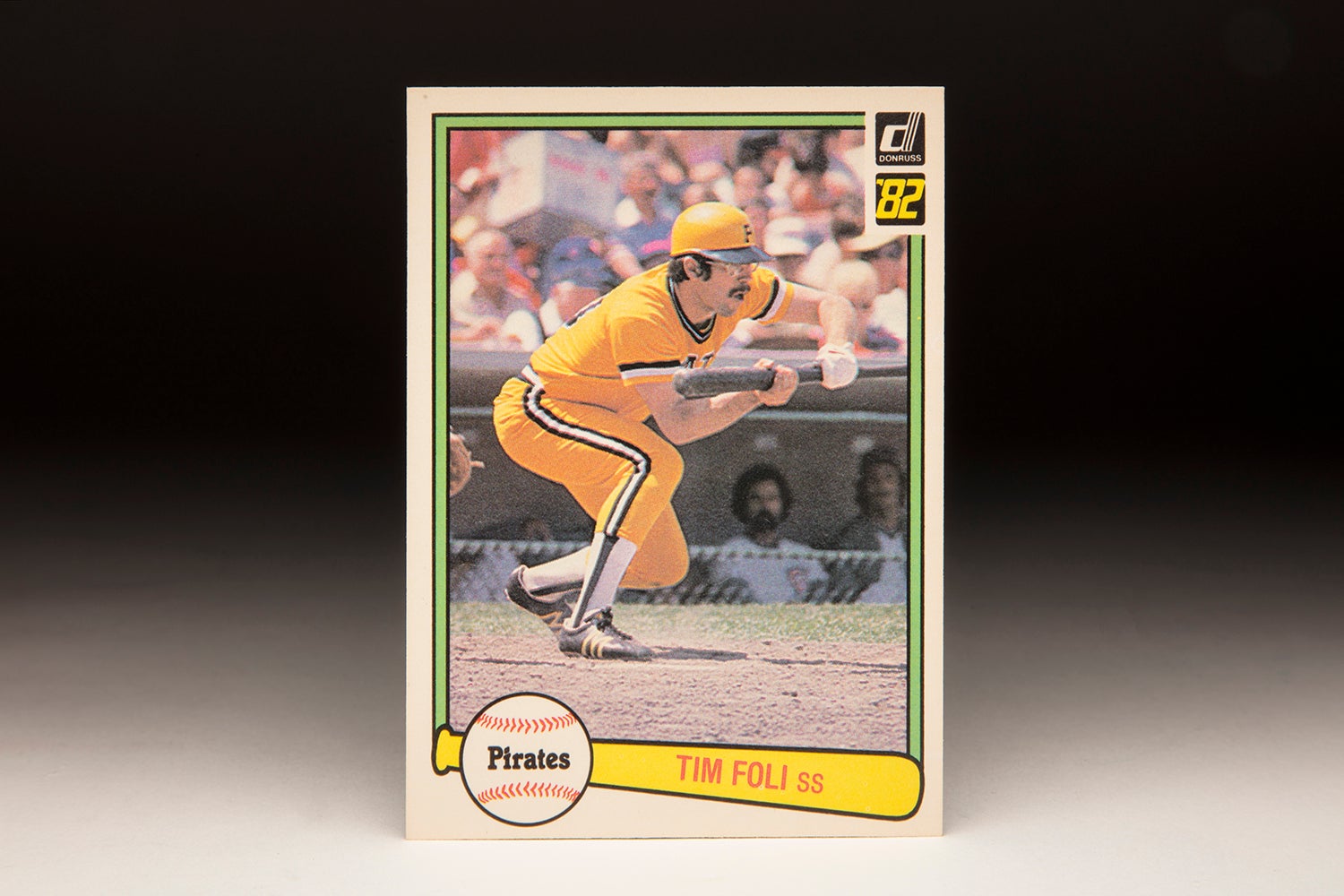

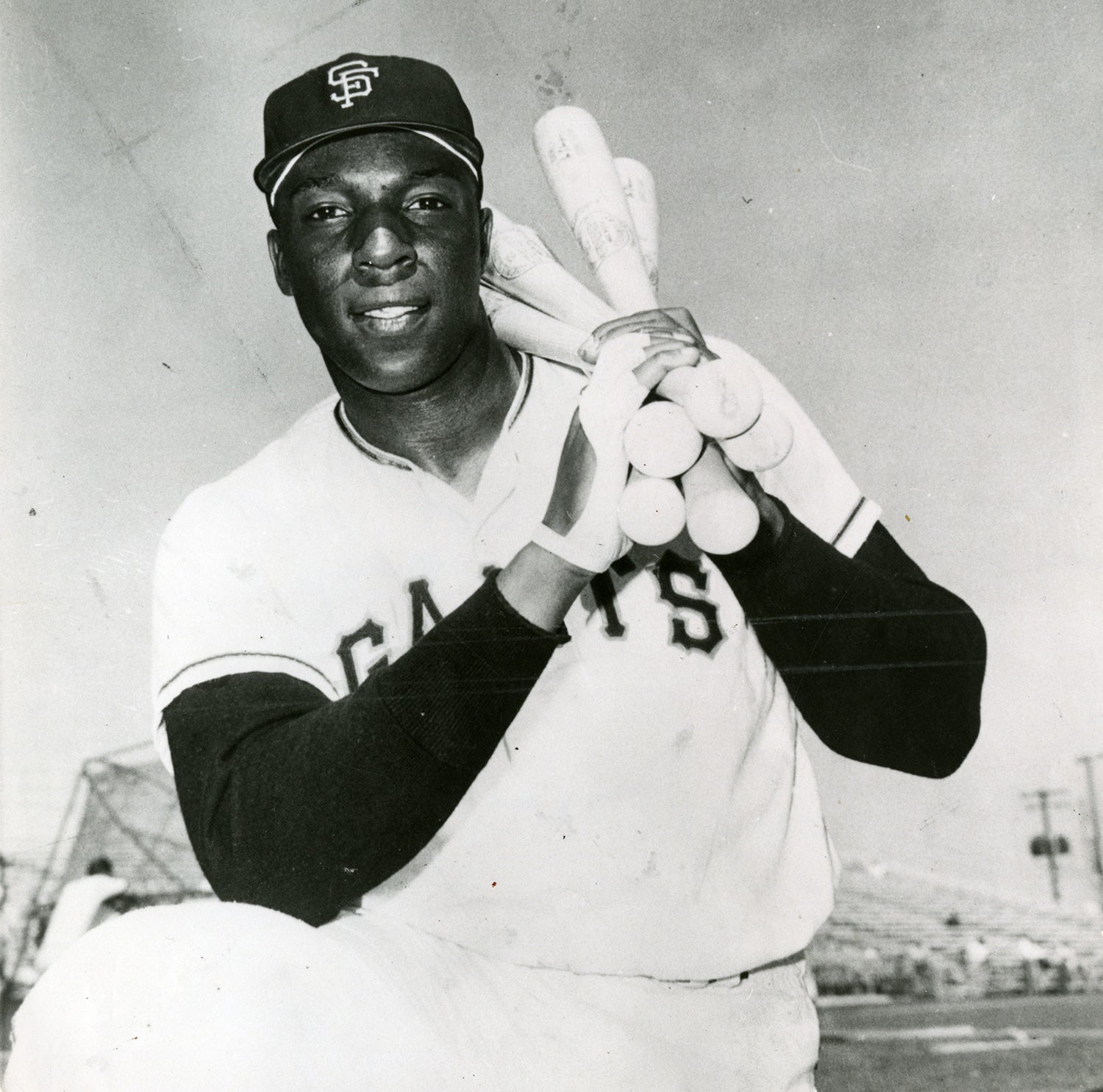

Moments before, Stennett had raised his batting average to .336 with an eighth-inning single. But the next batter, Ed Ott, followed with a ground ball to the Giants’ Willie McCovey at first base. Stennett, thinking there would be a play at second, slid awkwardly after Giants shortstop Tim Foli yelled “no play” as McCovey took the force out at first base.

Stennett’s spikes caught the dirt, and his right ankle and fibula snapped.

Pirates Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

“I hated to see it,” Foli told the Pittsburgh Press. “It was an unfortunate thing to happen. He was having such a great season.”

Two years later, Foli and Stennett would be on the same side as the “We Are Family” Pirates won the World Series. But Stennett’s career was altered forever that August day at Three Rivers Stadium.

It was a career that took him from the Panama Canal Zone to the heights of big league baseball.

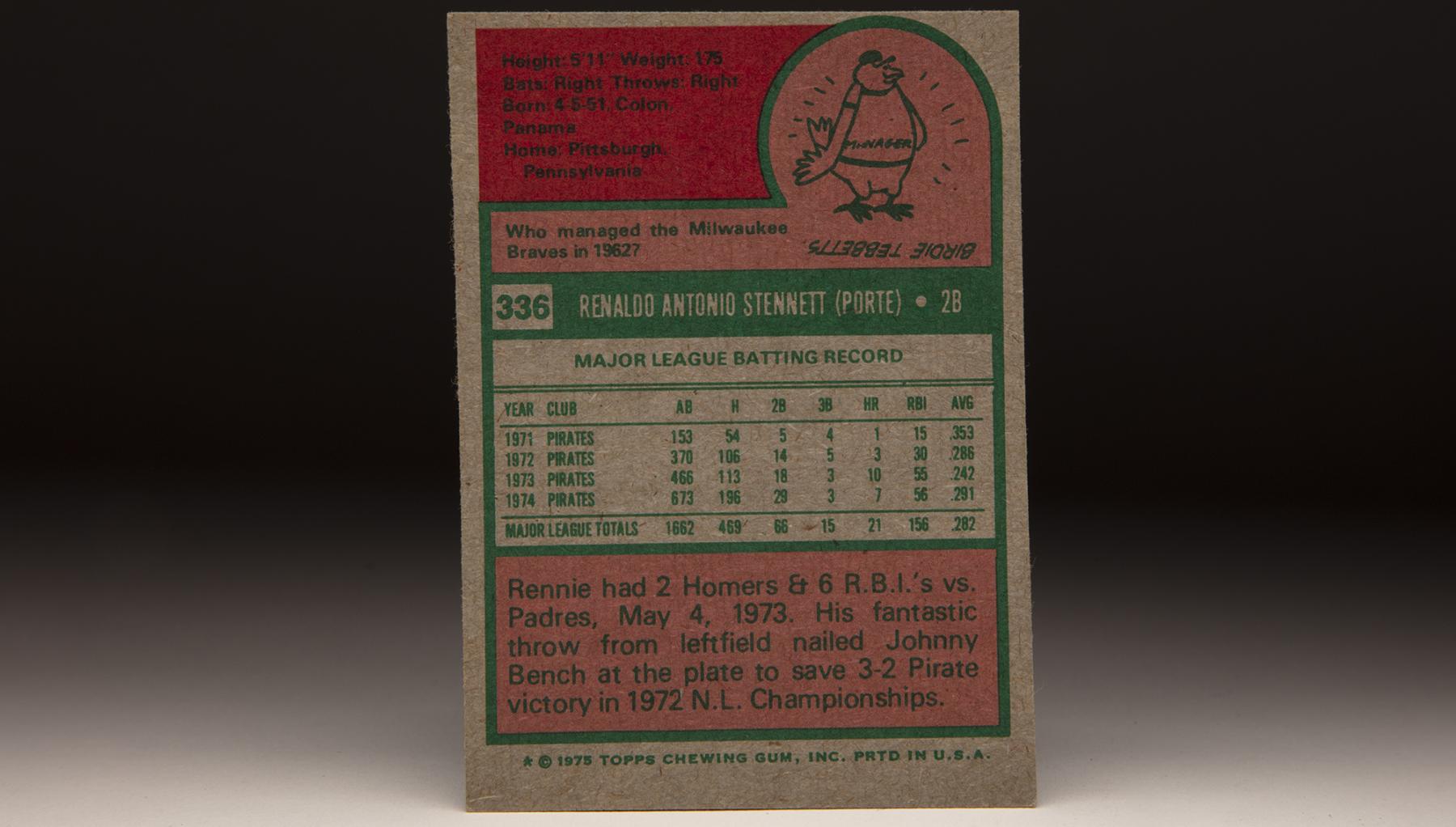

Born April 5, 1951, in Colón, Stennett grew up the son of a tugboat operator in an English-speaking household. A multisport athlete as an amateur, Stennett was originally a pitcher before signing with the Pirates as a free agent on Feb. 12, 1969.

Moved to the outfield, Stennett hit .288 for Class A Gastonia in 1969, then stamped himself as a top prospect by hitting .326 with Class A Salem in 1970, leading the Carolina League in batting average and hits (176). Following the season, the Pirates moved Stennett to second base.

Starting the 1971 campaign with Triple-A Charleston of the International League, Stennett hit .344 with 111 hits and 61 runs scored in 80 games. On July 10, with Pirates starting second baseman Dave Cash out of action due to his military commitment, Stennett was summoned to Pittsburgh.

Playing second base and leading off against the Braves and future Hall of Famer Phil Niekro, Stennett went 0-for-4 off Niekro’s knuckleball in Pittsburgh’s 5-4 victory. He received irregular playing time for the next five weeks before teammate José Pagán suffered a broken arm and Richie Hebner was sidelined with an illness. Then – starting Aug. 22 – Stennett stepped into the lineup and responded with an 18-game hitting streak, batting .463 with 37 hits, 18 runs scored and 10 RBI as the Pirates went 13-5 to take control of the National League East.

“I’m not surprised at Stennett’s ability to hit the ball,” Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh told the Charleston Daily Mail. “But anytime a guy hits over .400 you have to be a little surprised.”

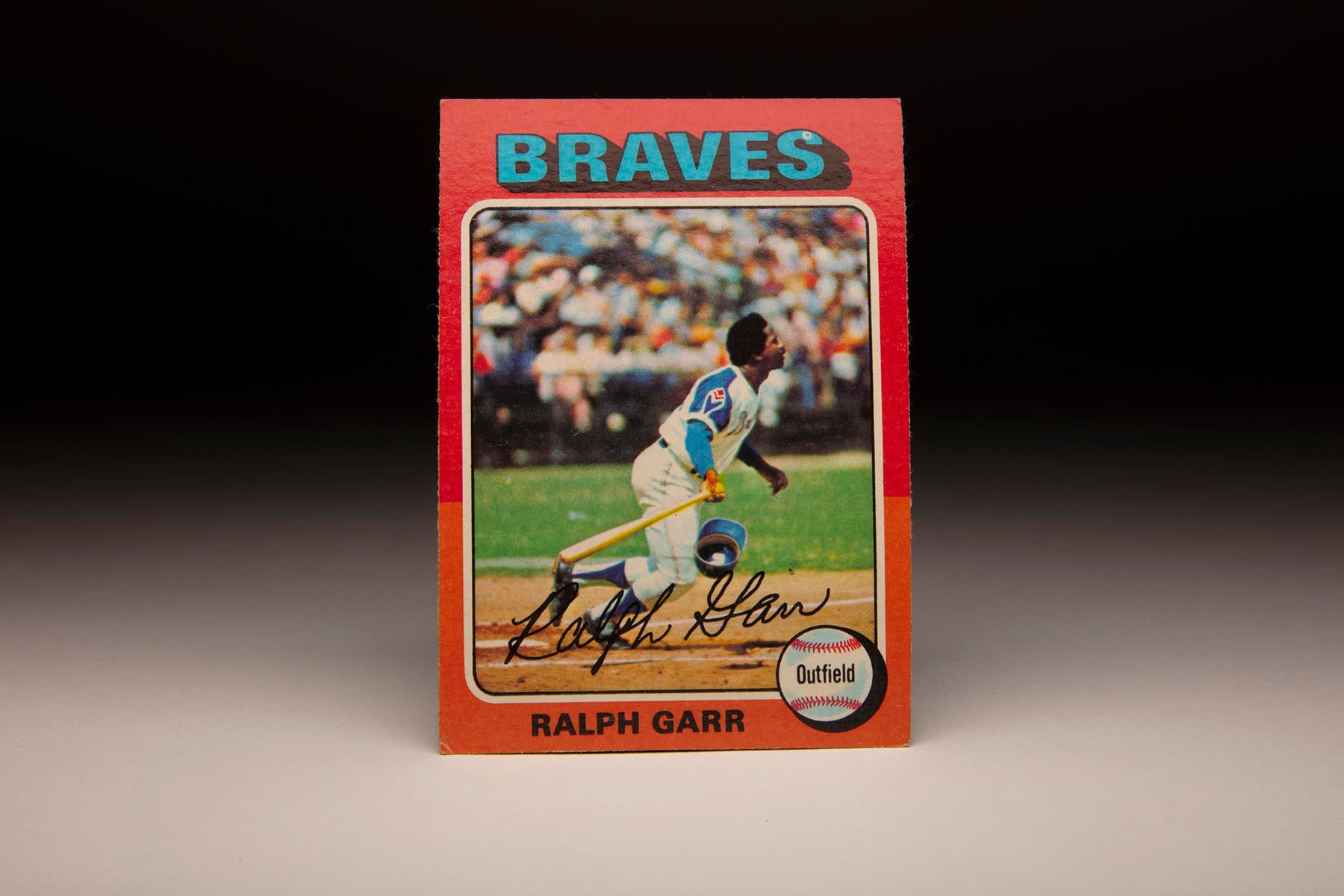

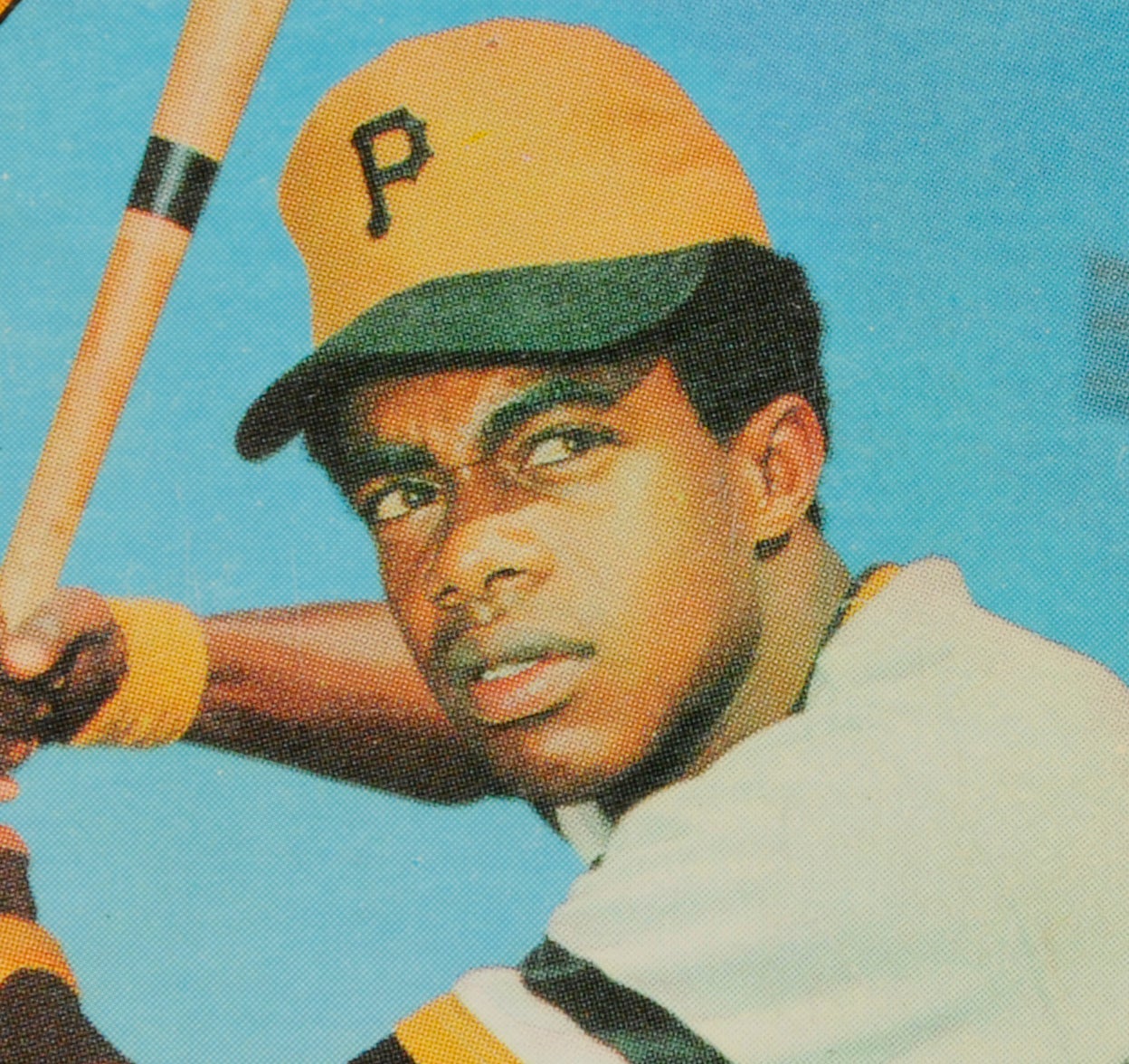

During that stretch, Stennett made history as part of the first all-Black lineup in an MLB game. The starting nine Murtaugh sent out that Sept. 1 night against the Phillies include Stennett at second base, Gene Clines in center field, Roberto Clemente in right, Willie Stargell in left, Manny Sanguillen behind the plate, Cash at third base, Al Oliver at first, Jackie Hernández at shortstop and Dock Ellis on the mound.

Stennett finished the season with a .353 batting average in 50 games. But with Pagán’s arm healed, Murtaugh opted for experience and kept the veteran on postseason roster instead of Stennett – who was still struggling with his defense.

“Rennie Stennett’s position,” wrote Dick Young of the New York Daily News, “is batter.”

Pagan would make Murtaugh look good by driving in what proved to be the winning run in Game 7 of the World Series against the Orioles, doubling home Willie Stargell in the eighth inning. But while Stennett missed the opportunity to play in a World Series, he had clearly established himself as part of the Pirates’ future.

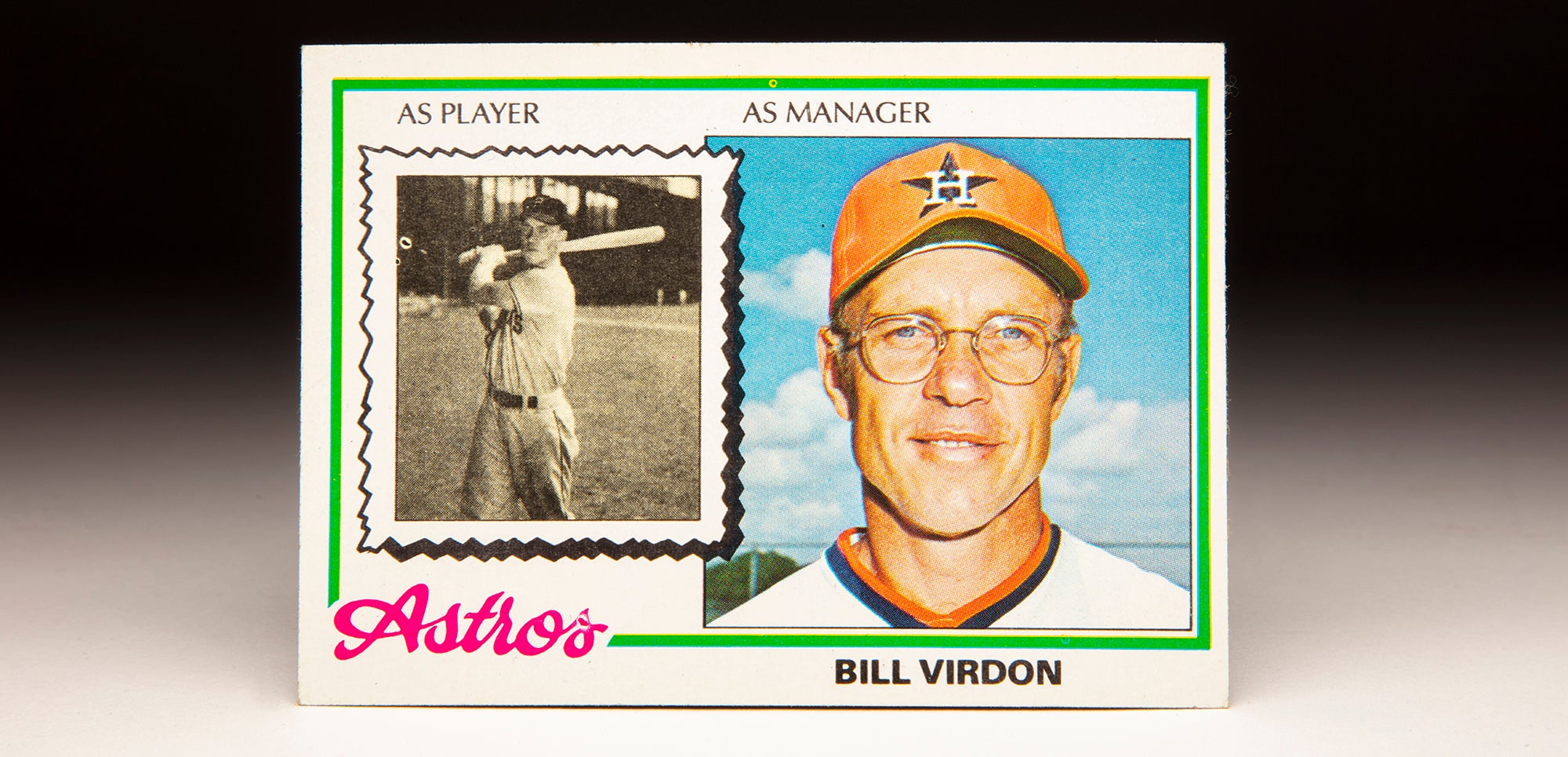

Stennett made the Pirates’ Opening Day roster in 1972 when Bill Mazeroski was sidelined with a bad back. Cash was still the starter at second base, but Stennett – who was diligently working on his defense – forced new manager Bill Virdon’s hand by hitting a blistering .400 as late as June 2.

“He’s like a young (Roberto) Clemente,” Reds catcher Johnny Bench told the Dayton Daily News. “He’s got a decent eye, but he’s up there slashing away just the way Clemente does. You think you’ve got him figured out on one pitch and then he gets another hit.”

Virdon used Stennett at second base and in the outfield throughout the summer, and Stennett finished with a .286 batting average in 109 games. The Pirates again won the NL East – and this time Stennett was on the postseason roster, starting all five games of the NLCS vs. the Reds in left field. Stennett hit .286, but the Pirates fell to Cincinnati 4-3 in Game 5 on a walk-off wild pitch that scored George Foster.

On Dec. 31, 1972, Clemente died in a plane crash in Puerto Rico. Stennett was in Puerto Rico at the time, playing winter ball.

By the time Spring Training rolled around, Stennett had improved his defense enough to be seen as a possible shortstop – a position the Pirates had struggled to fill for several years. But Virdon preferred Stennett at second base and started him there before moving him to shortstop until mid-July. At that point, Stennett returned to second when the Pirates acquired veteran Dal Maxvill, with Cash relegated to a reserve role.

The Pirates, however, finished 80-82 – and Stennett hit just .242 while bouncing around the diamond. He did, however, set career-highs with 10 homers and 55 RBI.

“He’s never really had a chance to learn one position,” said Virdon, who was fired before the end of the season.

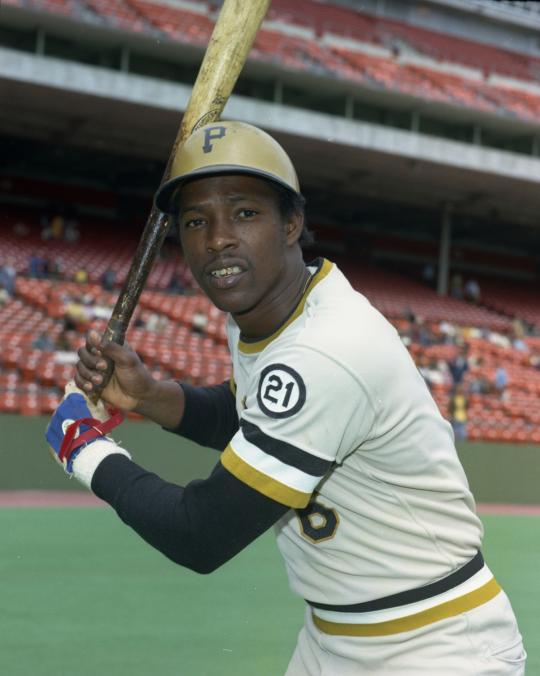

But with Murtaugh returning to the dugout in 1974, Stennett got that chance. Cash was traded to the Phillies on Oct. 18, 1973, for pitcher Ken Brett, and Stennett moved into a starting role at second base.

“It’s a good feeling to know the job is mine,” Stennett told the Pittsburgh Press. “I definitely think I’m a .300 hitter. I want to prove to everyone that I am the good hitter I showed when I first came up.”

Stennett played in 157 games in 1974, overcoming a summer slump with a hot September to finish at .291 with 196 hits, 29 doubles and 84 runs scored. The Pirates won the division title for the fourth time in five seasons, but the Dodgers defeated Pittsburgh in the NLCS as Stennett went 1-for-16 at the plate.

Stennett’s 1975 season was a virtual duplicate of the year before as he hit .286 with 176 hits and 89 runs scored in 148 games. The highlight of his season came on Sept. 16 when he went 7-for-7 in a 22-0 Pirates win against the Cubs at Wrigley Field, becoming the first player in the modern (post 1900) era to get seven hits in a nine-inning game.

“I don’t think about records,” Stennett told the Pittsburgh Press. “I thought someday I might get five hits in a game, but I never dreamt I’d get seven.”

The bat Stennett used in the game is a part of the Hall of Fame collection.

The Pirates again won the NL East, but this time were swept by the Reds.

Stennett’s average dropped to .257 in 1976, but his once-shaky defense remained steady, as he committed just 18 errors while leading the league in putouts (430) while finishing second in assists (502). Murtaugh died following the 1976 season, but new manager Chuck Tanner stuck with Stennett at second base and was rewarded with Stennett’s best campaign -- up until the injury. With Stennett sidelined, the Pirates were unable to catch the division-leading Phillies despite winning 96 games.

Stennett appeared to be back to form early in the 1978 season, but his batting average began to plummet in June. By July, Tanner had moved third baseman Phil Garner to second base and relegated Stennett to a reserve role as Pittsburgh futilely chased the Phillies – finishing one-and-a-half games back in the NL East. Stennett hit .243 in 106 games, often favoring his right ankle – especially late in games.

He pronounced himself healthy in the spring of 1979 and started at second base for most of the first three months of the season. But he was hitting just .236 on June 28 when the Pirates acquired two-time batting champion Bill Madlock from the Giants. At that point, Tanner installed Madlock at third base and moved Garner back to second, sending Stennett to the bench.

Stennett appeared in only four games in September but was on the roster for both the NLCS and World Series, getting into one game in each series as the Pirates won the title.

Following the season, Stennett became a free agent and quickly signed a five-year, $3.25 million contract with the Giants.

“I’m 100 percent physically, so there’s no reason I can’t play every day next year and make a contribution,” Stennett told United Press International.

At just 28 years old, Stennett appeared to be entering his prime. But over the next two seasons, Stennett appeared in only 158 games hitting .242 with a .295 slugging percentage. He hit .118 in eight games with San Francisco in Spring Training of 1982 before the Giants waived him April 2. He quickly rejoined Pittsburgh, but did not make the Opening Day roster.

He played in 46 games with Reynosa of the Mexican League that year, hitting .326. He hooked on with Montreal’s Triple-A team in Wichita in 1983, hitting .309 in 55 games before hanging up his spikes. But he returned to the Pirates in Spring Training of 1989 despite having not played a professional inning since the 1983 season. He played in exhibition games but failed to make the Opening Day roster, ending his career.

“I’m having fun. I’m not asking for anything,” Stennett told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “My heart has always been with Pittsburgh.”

Stennett finished his 11-year big league career with a .274 batting average, 1,239 hits and 500 runs scored. He passed away on May 18, 2021.

“I just want to play every day and try to hit .300,” Stennett told the Pittsburgh Press in Spring Training of 1979. “I don’t want to worry about my ankle.”

He never hit .300 over a full season. And his ankle injury sidetracked his career. But Rennie Stennett left his mark on baseball – and a historic bat in Cooperstown.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum