- Home

- Our Stories

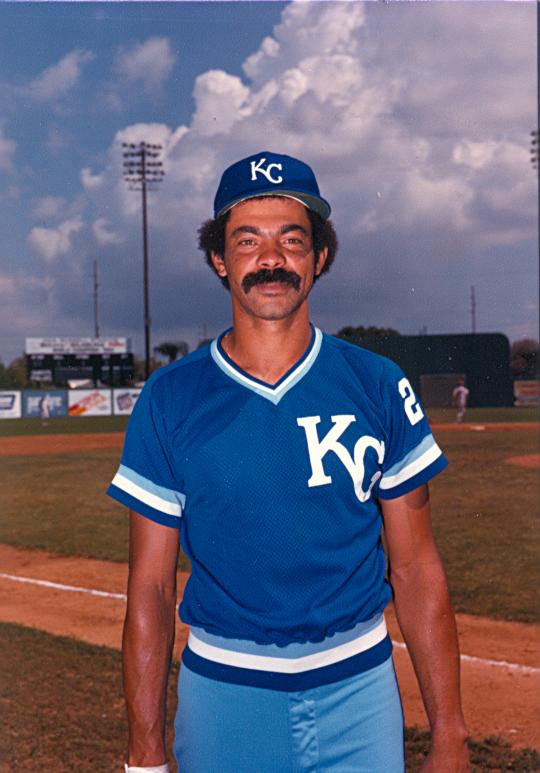

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps César Gerónimo

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps César Gerónimo

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

They don’t make mustaches like this anymore.

Few players in today’s major league game wear mustaches at all, and if they do, they are often found in tandem with beards. The few players who do have mustaches generally prefer the thinner, more subtle kind.

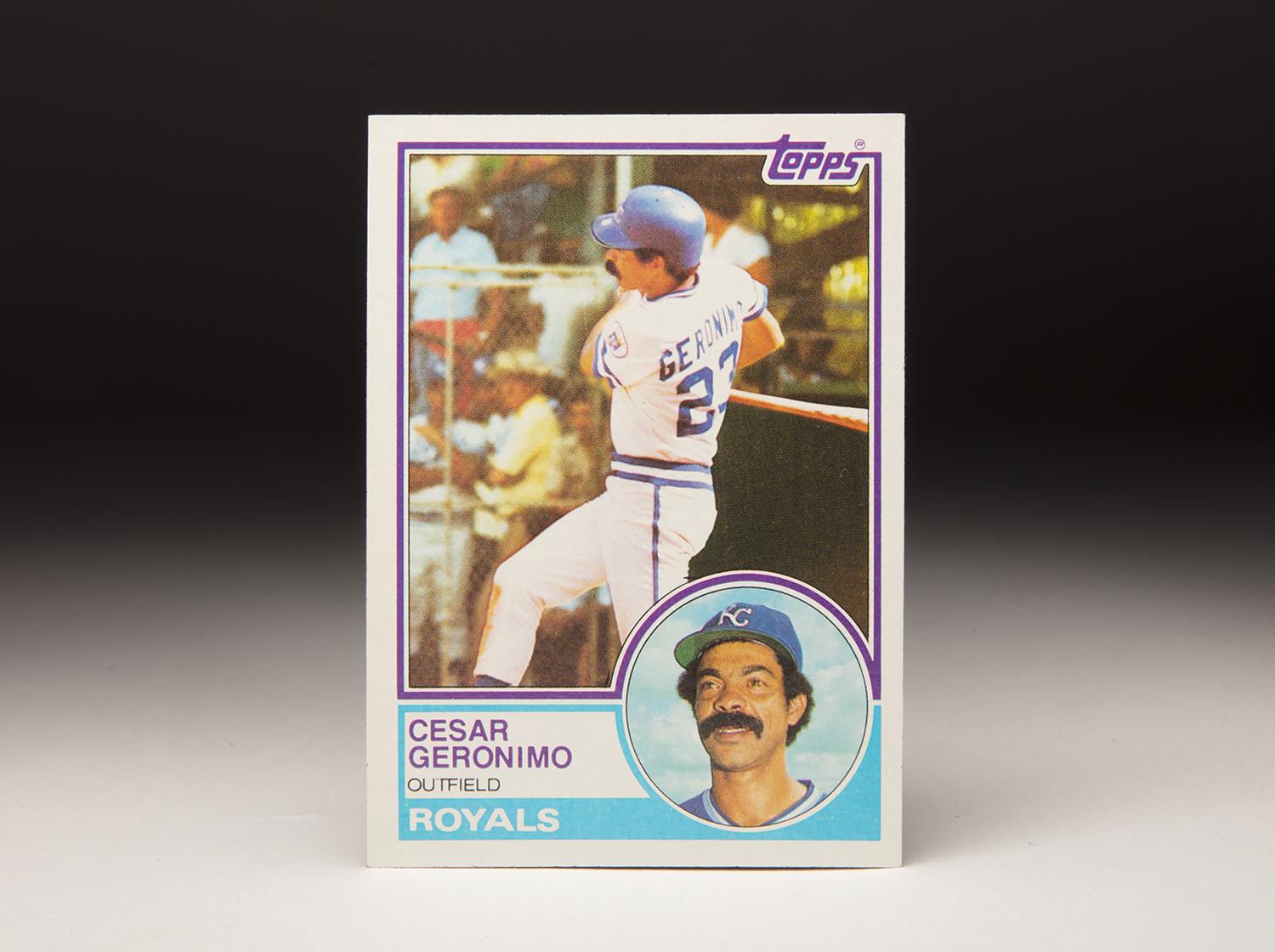

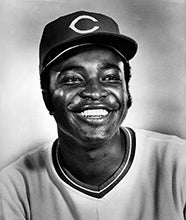

The thin mustache was not the fashion choice of Cesar Geronimo. He preferred the old-school mustache – thick and bushy, to the point where it almost consumed his upper lip. The Geronimo mustache is fully evident in the small portrait shot contained on his 1983 Topps card. Even the larger photograph, an action shot taken from the side, shows off a large hint of the mustache.

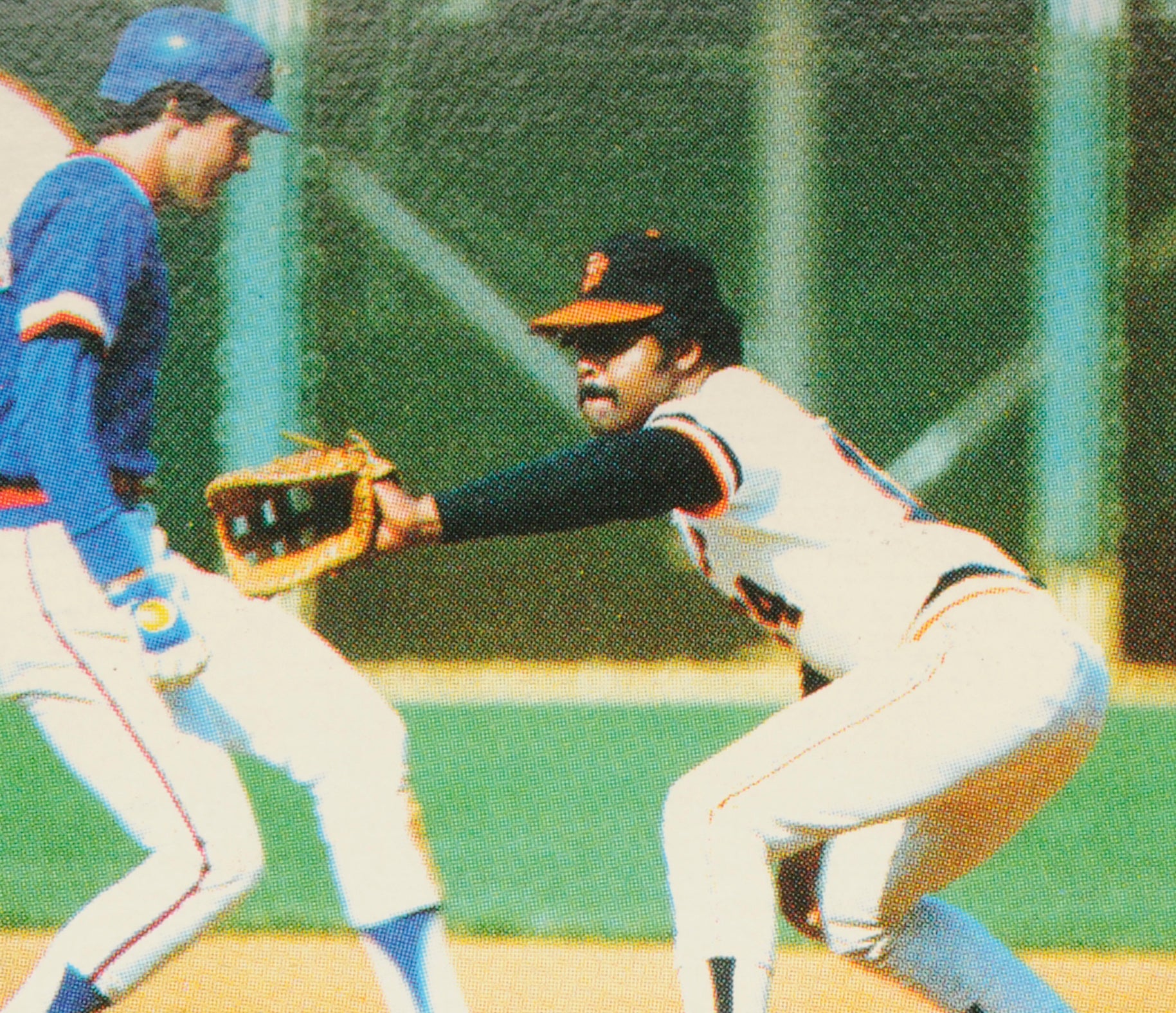

Geronimo’s mustache is not the only intriguing feature to his 1983 card. The Topps photographer, perhaps shooting from the third base dugout, has captured Geronimo near the end of his swing, so that his bat is completely wrapped around his body, with the handle and the very end of the bat obscured from our viewed. We see very little of his face, but have a good view of his name, GERONIMO, which boldly marks the back of his jersey.

From this angle, we can also see part of the stands in the background, including the older man in the yellow shirt. This background is a source of confusion for me. The man appears to be an usher of some sort, but why is he standing next to what appears to be a Kansas City coach, who is outfitted in his full Royals uniform? I’m not sure why the Royals coach would be standing behind the fence, unless this is the extreme corner of the dugout. Whatever the case, this doesn’t look like Kauffman Stadium to me; I’m guessing that this shot was taken at the Royals’ Spring Training site in Fort Myers, Fla., at a ballpark called the Terry Park Ballfield.

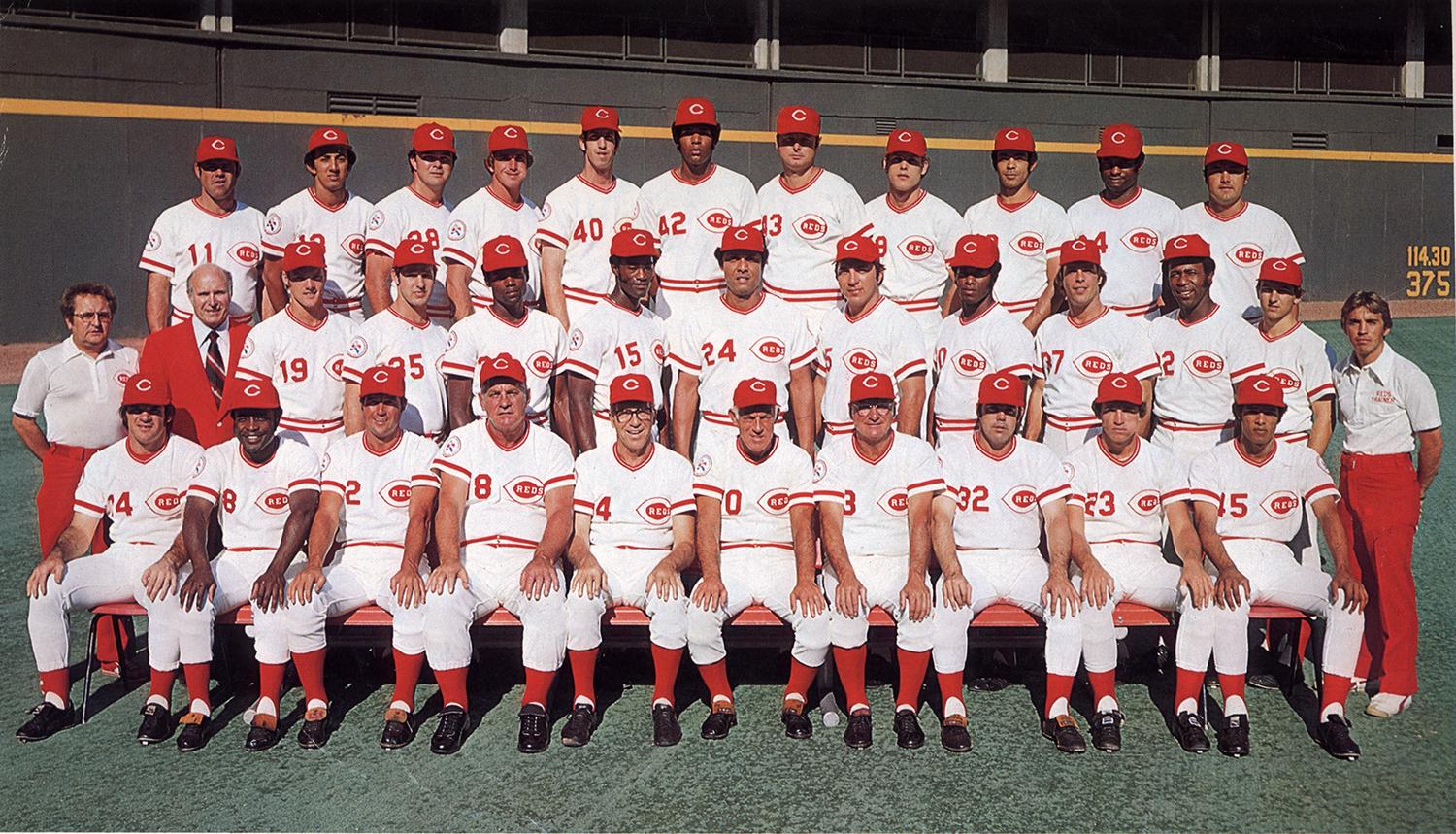

Geronimo is seen wearing the home uniform of the Royals, which is not the team with which we normally associate him. Geronimo spent his prime years playing for the Cincinnati Reds, the team that acquired him from the Houston Astros in the blockbuster trade involving Joe Morgan. Geronimo’s time in Cincinnati coincided with the era of the “Big Red Machine,” a lineup that included Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez. Geronimo played a major role in two World Championships, as the Reds dominated the baseball world in 1975 and ’76.

Given his successful run with the Reds, it’s easy to forget that Geronimo ever played for the Royals; he did not join them until 1981. By then, he was no longer an everyday player, but an aging performer filling a backup role behind players like Willie Wilson, Amos Otis and Jerry Martin.

That Geronimo was still playing in the major leagues in 1983 was a tribute to his longevity – and also something of an unlikely development. As a teenager growing up in the Dominican Republic, Geronimo had attended seminary school with the expressed purpose of becoming a Catholic priest. He spent a total of four years at the seminary.

Only one obstacle remained in his pursuit of becoming a priest – and that was baseball. “I liked it [being] at seminary, but I really wanted to be a ballplayer,” Geronimo once told sportswriter Ritter Collett, “and I knew if I went on to become a priest that would never happen.”

In 1967, despite a lack of much on-field baseball experience, Geronimo attended tryouts with the both the New York Mets and Yankees. This was a rather remarkable occurrence, given that Geronimo’s high school in the Dominican did not have a baseball team. As an amateur, he had played soccer, basketball and slow-pitch softball. But he had one trait that played especially well on the baseball diamond: A phenomenal left arm, which so caught the eye of Yankees talent evaluators that they signed him to his first pro contract. Just like that, the plans of becoming a priest moved off to the side.

Geronimo had grown up as a fan of the Yankees, so the signing represented the best possible outcome. The Yankees assigned Geronimo to their affiliate in little Oneonta, N.Y., an outpost located not far from Cooperstown. Geronimo played only four games for Oneonta, where he batted .100, before being assigned to Johnson City, where his batting average fell to .071 in 19 games. Geronimo was completely overmatched by pitchers in Class A baseball, a development that was not surprising given his lack of experience.

In 1968, the Yankees moved Geronimo to the Florida State League. He hit a little better, but a .194 batting average over 109 games did not inspire much hope for future advancement. The Yankees began to contemplate the possibility of using Geronimo as a fulltime pitcher, where his throwing arm could best be utilized. The Yankees had used him as a pitcher for one minor league game in 1967, but with less than desirable results.

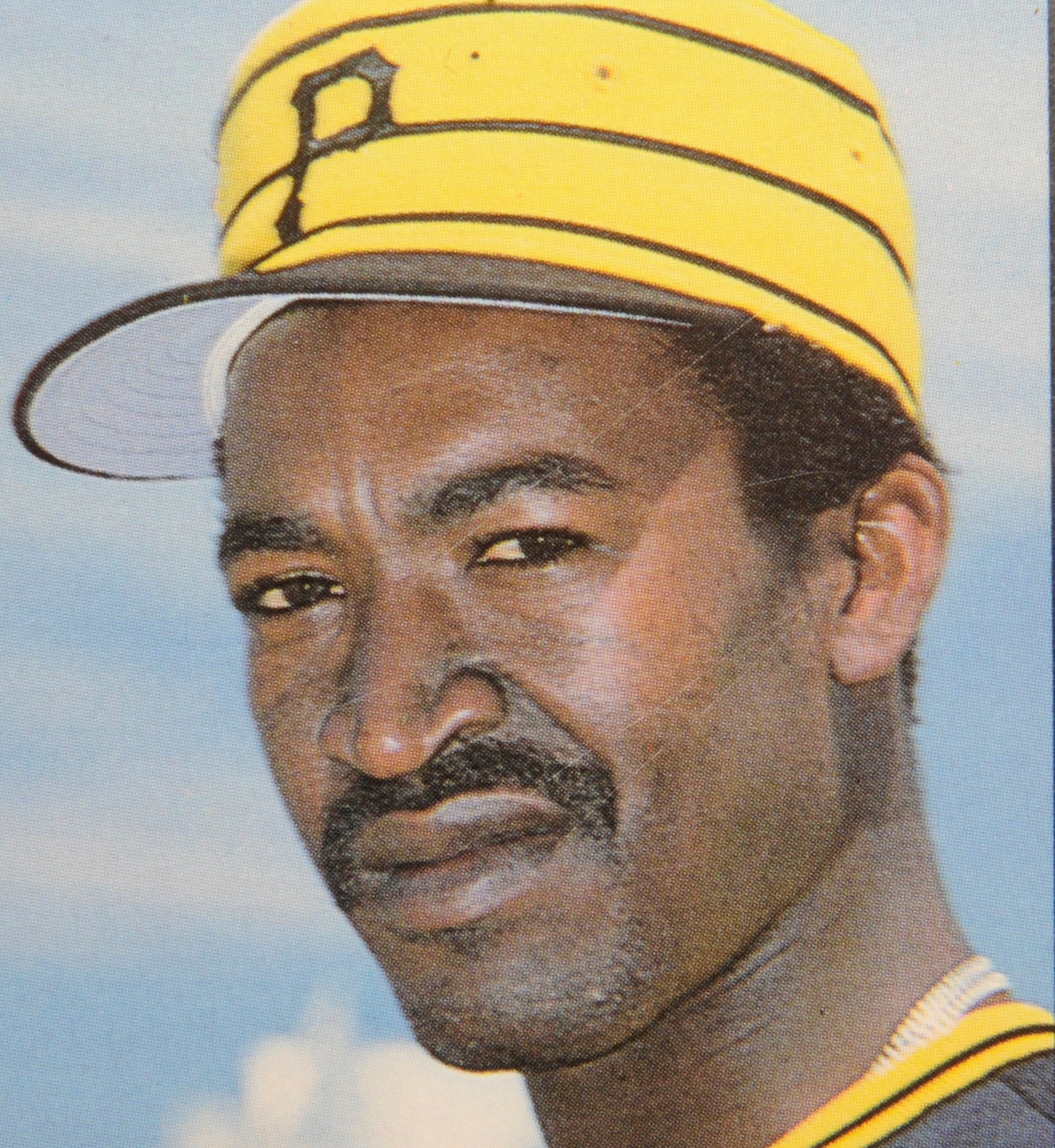

But the Yankees would never have the chance to convert Geronimo from the outfield to the pitcher’s mound. Although Geronimo had played only two seasons in the minor leagues, the rules of the day dictated that he was now eligible to be taken by another team in the Rule 5 draft. The Houston Astros, based on a report they heard from rival scout Howie Haak (working for the Pittsburgh Pirates), decided to take a chance on Geronimo, paying all of $8,000 for the right to draft him. The one caveat? The Astros would now have to keep Geronimo on their major league roster for all of 1969, or else offer him back to the Yankees for half of the Rule 5 price.

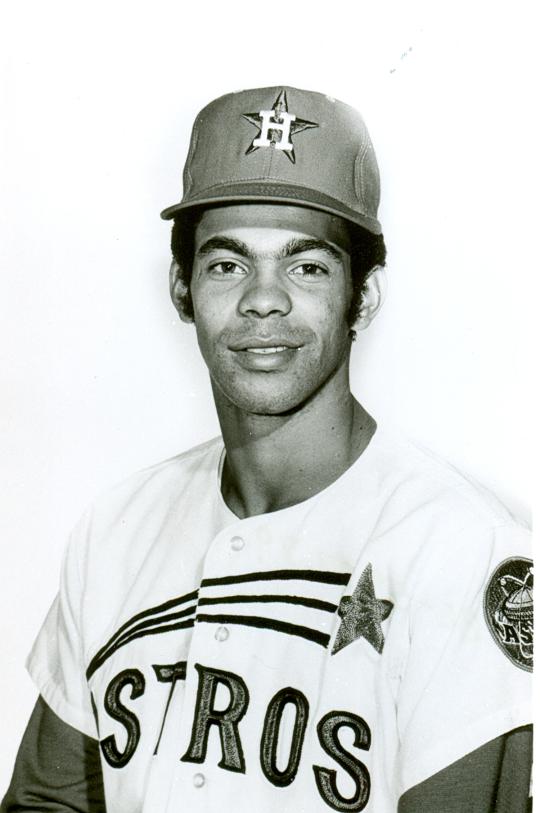

Although clearly not ready to hit at the major league level, Geronimo kept his place on the Astros’ roster the entire season. He came to bat only eight times, picking up two hits. In total, Geronimo appeared in 28 games, mostly as a defensive substitute. Blessed with a lanky build, Geronimo covered acres of ground with his long strides, giving him more range than any other outfielder on the Astros’ roster. Unlike the average center fielder, Geronimo possessed a powerhouse arm, too, which made him more than capable of playing right field.

With the Rule 5 requirement now fulfilled, the Astros sent Geronimo back to the minor leagues in 1970. They assigned him to Double-A Columbus, where he showed major improvement as a hitter. He hit a respectable .269, while playing a stellar center field. Duly impressed, the Astros brought him back to the major leagues in midsummer.

Geronimo continued his apprenticeship in the Dominican Winter League, where he played so well that the Astros regarded him as a legitimate candidate to make their roster out of Spring Training in 1971. Geronimo not only made the team, but immediately opened eyes on Opening Day by unleashing a cannonlike throw from the left field corner and nailing Duke Sims of the Los Angeles Dodgers at third base.

Appearing in 94 games, mostly as a defensive specialist and pinch-runner, Geronimo did well off the bench. From an offensive standpoint, he came to bat only 82 times and delivered a .220 batting average, an indication that his hitting still lagged behind the rest of his game. The Astros felt that he was a special talent defensively, but wondered if he ever would hit enough to become an everyday player.

Ultimately, the Astros decided that Geronimo was expendable. They already had a budding young superstar center fielder in Cesar Cedeno, so Geronimo logically became trade bait. At the famed 1971 Winter Meetings, the Astros agreed to include Geronimo in a blockbuster eight-man trade with the Reds. The principals in the deal were Joe Morgan (going to the Reds) and Lee May (coming back to the Astros), but the Reds felt that Geronimo was capable of becoming an everyday player for their budding dynasty. They also felt that a strong defensive outfielder with speed was a necessity for their expansive new home park, Riverfront Stadium, which had replaced the ancient Crosley Field in June of 1970. With an artificial turf surface, Riverfront required speedy outfielders who could make long throws from the outfield wall.

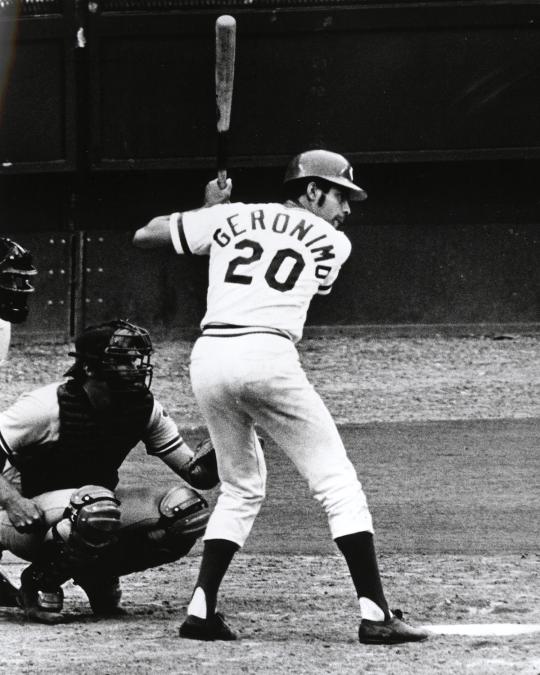

The Reds already had the highly capable Bobby Tolan available to play center field, so they moved Geronimo to right field. They also put the youngster to immediate work with batting instructor Ted Kluszewski, who revamped Geronimo’s swing. The work paid off; Geronimo batted a respectable .275 in 120 games, while posting an OPS of .756. For a player who had once struggled to hit even .200 in Single-A ball, the transformation in Geronimo’s hitting was remarkable.

Geronimo’s rise as a hitter coincided with the Reds’ return to the World Series, where they had last played in 1970. Geronimo played every game during the Reds’ 1972 postseason run, but struggled badly at the plate, picking up only five hits in 39 at-bats. In the meantime, the Reds lost a tightly-fought World Series in seven games.

In 1973, the Reds flip-flopped Tolan and Geronimo, placing the latter in center field. Geronimo had no trouble readjusting to center field, but did suffer an injured shoulder while making a diving catch. The injury bothered Geronimo at the plate; his batting average fell to .210 and his OPS to .574.

After the disappointing season, Geronimo followed his usual routine by playing winter ball in the Dominican. This time, the winter season gave him the chance to work with future Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda, who was managing in the DR. Lasorda put in some time with Geronimo, working with him on his stroke and approach at the plate.

Once again, hard work paid off. Geronimo returned to the Reds’ lineup in 1974, batting .281 over a full season. He also started to receive some acclaim for his stellar play in the outfield. The National League voted him his first Gold Glove Award.

In 1975 and ’76, the Reds took a step up, emerging as an elite team and winning back-to-back world championships. Though usually overshadowed by the likes of Johnny Bench, Tony Pérez, George Foster and Morgan, Geronimo played his part. He won two more Gold Glove Awards, batted .280 in the ’75 World Series and put up a career-best .307 mark during the 1976 regular season, earning some back-of-the-ballot support for the National League MVP.

In Game 3 of the 1975 World Series, a classic seven-game tilt with the Boston Red Sox, Geronimo scored the game-winning run, partly due to a controversial play. When Reds pinch-hitter Ed Armbrister collided with Carlton Fisk at the plate, resulting in an errant throw, Geronimo moved up to third base. He then scored on Morgan’s single, giving the Reds the win. In the meantime, Geronimo played his usually flawless center field. During the Series, Geronimo drew special attention from his manager. Sparky Anderson repeatedly told members of the media that Geronimo was the best defensive center fielder in either league and “just this short of Willie Mays.” As he made the comparison to the great Mays, Anderson held up his thumb and second finger just one inch apart.

In 1977, Geronimo added to his growing defensive reputation by winning his fourth consecutive Gold Glove Award. His batting average fell to .266, but he clubbed a career-high 10 home runs and stole 10 bases. His level of play remained high, but as a team, the Reds fell back after their peak play of 1976. The Reds won 88 games, a respectable total, but had to settle for second place in the National League West.

Over the next three seasons, Geronimo settled into a platoon role with the Reds, sharing time with younger players like Dave Collins and veterans like Ken Henderson and Paul Blair. By 1980, he lost the starting center field job to Collins, who was a more dynamic offensive player. That season, the Reds shopped Geronimo, sending him to the Royals for infield prospect German Barranca.

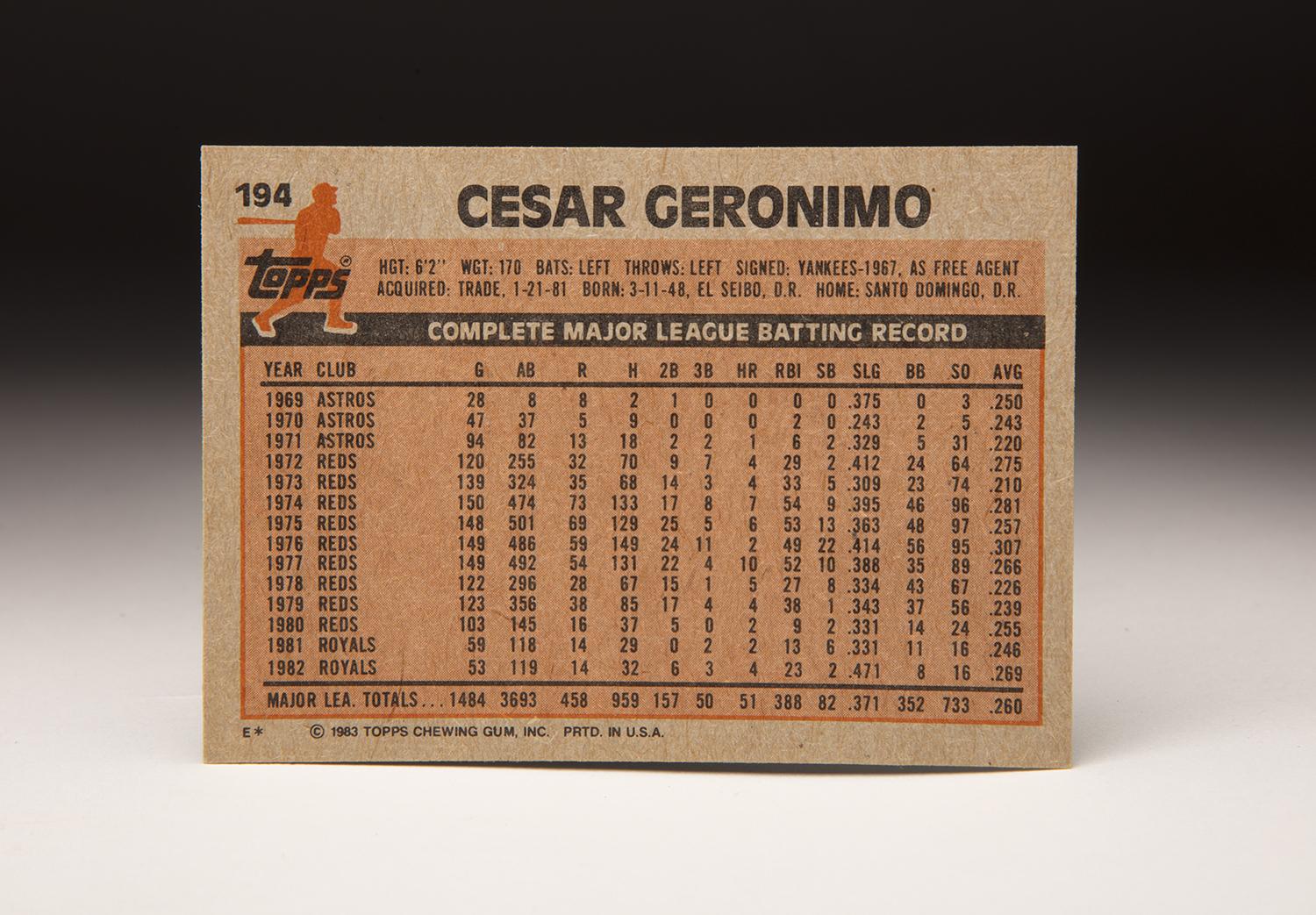

For the next three seasons, Geronimo filled a backup role with the Royals. He hit decently over the first two seasons, before his batting average dipped to .207 in 1983. After the season, the Royals released Geronimo, ending his 15-year career.

Rather than remain in Organized Baseball, Geronimo opted to work for an agency in the Dominican dedicated to preserving and improving rights of young players. He then joined a Dominican-based training camp run by the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, a team in the Japanese Leagues. He also became a founding member of a Dominican academy that established several goals, including improved physical training, financial advice and English lessons for young Dominican athletes.

Like so many players of his era, Geronimo has found success in passing on the wisdom of his own baseball career to younger generations, including the budding players of today. It’s an impressive legacy. It’s not quite what he originally planned to do, when he set his sights on becoming a Catholic priest, but it’s worked out pretty well for the man who mastered center field before mastering the art of helping those who have come after him.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital & outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum