- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Dan Quisenberry

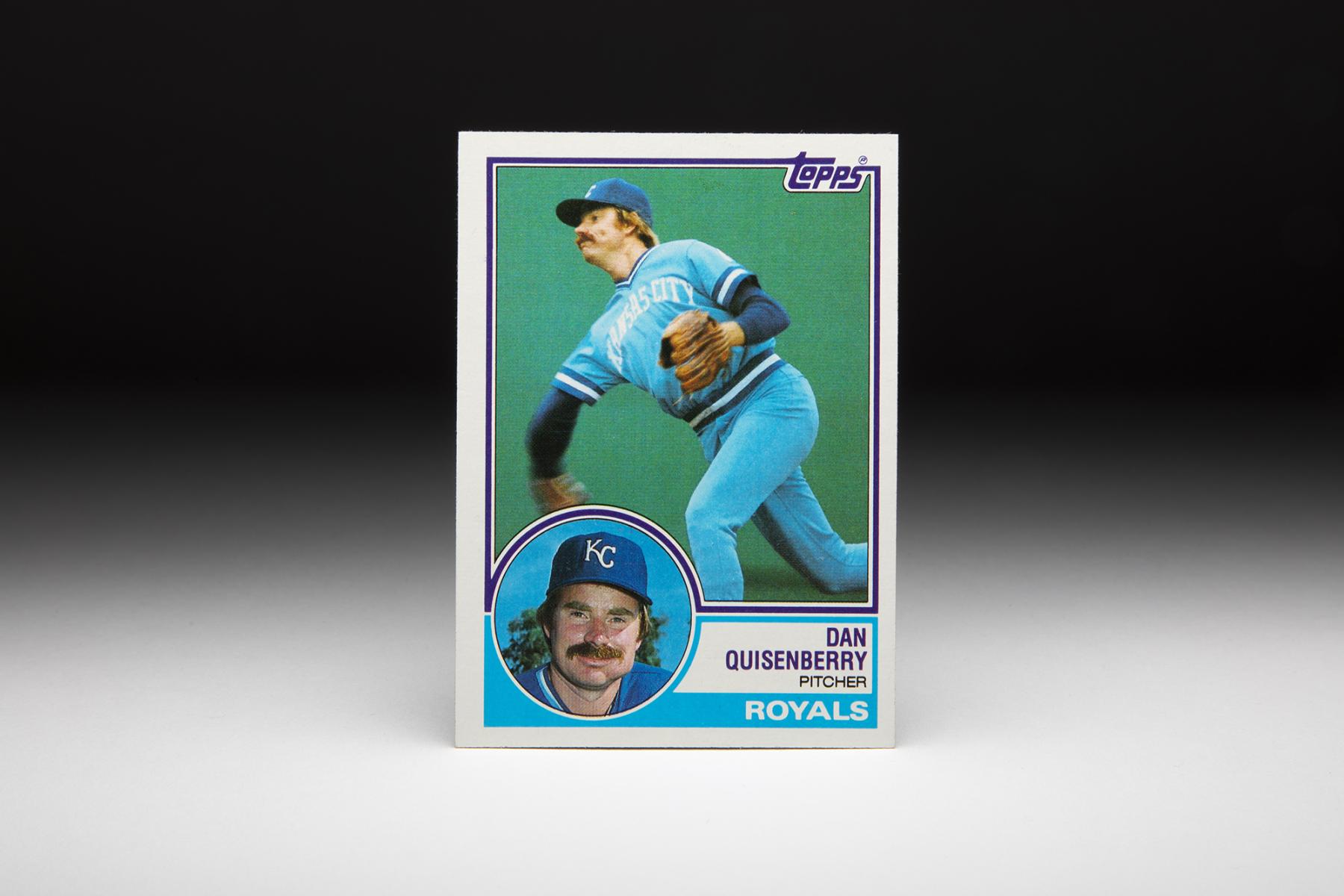

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Dan Quisenberry

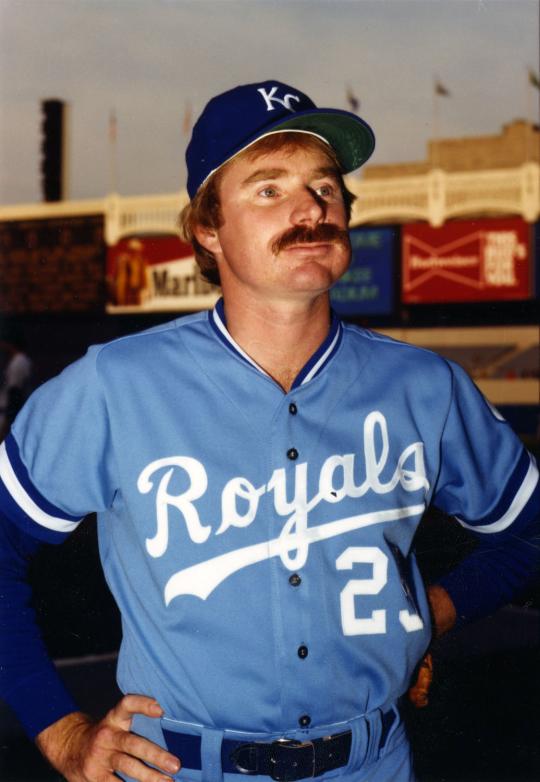

Dan Quisenberry’s 85 mile-per-hour fastball had batters sprinting to the plate to face him. And just as quickly, those batters were usually returning to the bench after a two-hopper to the shortstop.

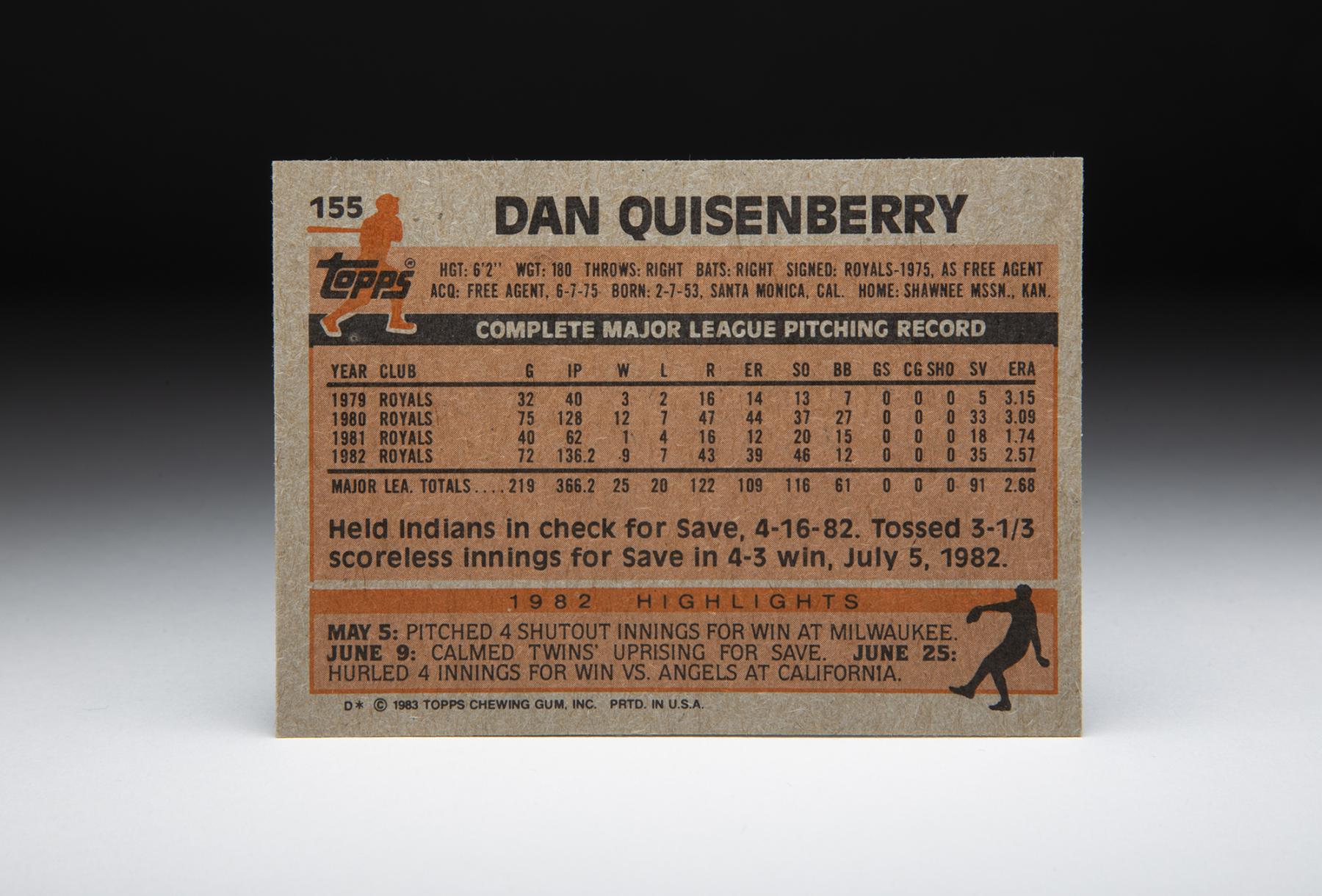

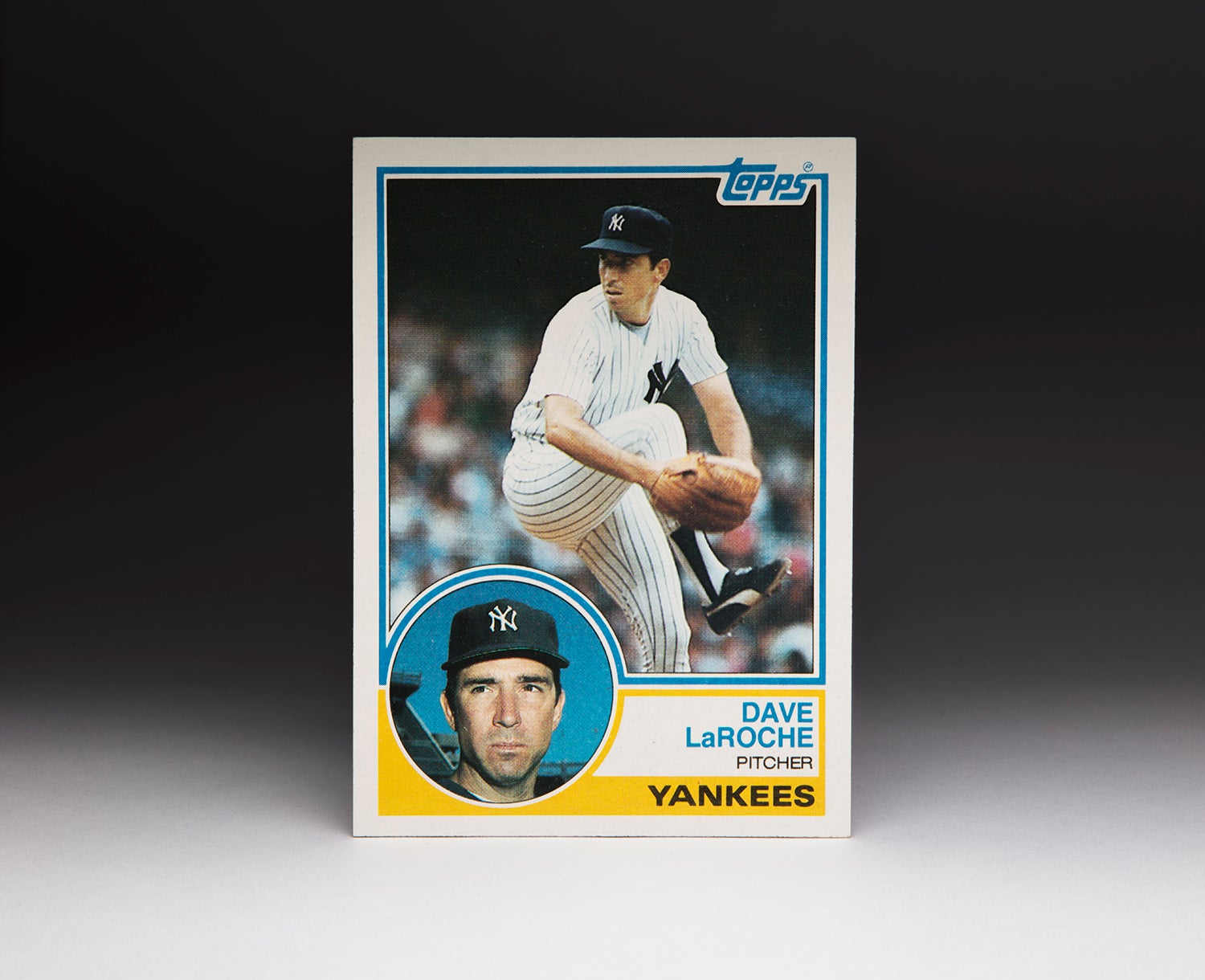

With a submarine delivery that produced one of the game’s best sinkerballs, Quisenberry became one of baseball’s top relievers of the 1980s. His 1983 Topps card catches him just before releasing the ball, with his right arm seemingly bent backwards at the elbow.

But Quisenberry’s delivery was deceptively easy on his arm, allowing him to work five different seasons with at least 128 innings pitched out of the bullpen. No other pitcher in history has more than three similar seasons.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Born Feb. 7, 1953, in Santa Monica, Calif., Quisenberry was a conventional right-handed pitcher at LaVerne (Calif.) College in the mid-1970s, throwing 194 innings as a senior starting pitcher – winning NAIA All-American honors – before toying with a sidearm delivery to rest his arm. He went undrafted after finishing college in 1975, but was signed as an amateur free agent that year by the Kansas City Royals.

“My arm was just all tired out after my senior season, so I thought I’d try it,” Quisenberry said of the submarine delivery. “I haven’t had a sore arm like I did sometimes throwing overhand.”

After starting his first minor league game for Class A Waterloo in 1975 (and pitching a complete game), Quisenberry was moved to the bullpen. He never started another game in professional baseball.

Success did not come easy in the minors – Quisenberry enrolled at Fresno State University is 1978 with plans to get a teaching certificate – but the Royals called him up to the majors in 1979, where he went 3-2 with five saves in 32 games that summer.

That winter, Quisenberry sought counsel from Pirates reliever Kent Tekulve, another submariner. With Tekulve’s help, Quisenberry mastered the sinker.

“At first, I felt off-balance,” said Quisenberry of the mechanical changes Tekulve suggested. “But the coaches said there was better movement on my ball, and gradually I adjusted. Tekulve was the tool that changed me.”

The next year, Quisenberry became an overnight sensation – going 12-7 with 33 saves for a Kansas City team that won the 1980 American League pennant. Quisenberry finished fifth in the AL Cy Young Award voting that year, one of five times he would crack the top five in his career.

Quisenberry recorded a 1.74 earned-run average and 18 saves in the strike-shortened 1981 season, then embarked on a four-year run of dominance.

From 1982-85, Quisenberry averaged seven wins and 40 saves a season, averaging an incredible 133 innings pitched as the Royals’ closer.

He led the AL in saves in each of those four seasons, and in 1985 he helped Kansas City win its first World Series title, picking up the win in Game 6.

From 1982-85, he finished either second or third in the AL Cy Young Award voting in every season. He set a new single-season saves record in 1983 with 45 when he was 5-3 with a 1.94 ERA.

Quisenberry expanded his pitching repertoire as the years passed, adding sliders and changeups and even a knuckleball to his bread-and-butter sinker.

But he never altered his submarine delivery.

“The ball sinks, and I’ve got good control,” Quisenberry said. “I keep it down, and I know how to pitch in and out. If you put those three together, they produce outs.”

They also produce success. Quisenberry reached 100 saves faster than any pitcher before him, and eventually signed a “lifetime” contract with the Royals in the mid-1980s.

“A lot of it has to do with the fact that I’m never in pain,” Quisenberry said. “I can throw three or four days in a row without it. Usually, after I’ve thrown four-plus days, I know it’s better to have an off day. But I’ve never told anybody that I couldn’t pitch. Never.”

Quisenberry told folks other things, however, becoming one of baseball’s most famous quipsters. “I have seen the future,” Quisenberry once said, “and it is a lot like the present, only longer.”

Quisenberry’s baseball future, however, began to erode when his sinker stopped sinking in the late 1980s. He had just 20 total saves from 1986-87, then spent his final three seasons as a set-up man for the Royals, Cardinals and Giants before retiring early in the 1990 campaign.

“That’s real life,” Quisenberry said. “It’s not always going to be: ‘Throw out the glove (and record outs)’ like it was in 1983. That wasn’t real life. You’ve got to struggle.”

His final totals: a 56-46 record with a 2.76 ERA and 244 saves. In 12 seasons, he walked just 162 batters – 70 of which were intentional. His walks per nine innings rate of 1.40 is the best of any live ball era (post 1919) pitcher with at least 1,000 innings pitched.

He allowed just 59 home runs – about one for every 18 innings he worked.

“I have no regrets,” said Quisenberry, a three-time All-Star, told the Associated Press when he retired on April 29, 1990. “I got to play all my dreams.”

Quisenberry was dedicated to many causes, including fighting hunger, and also wrote poetry. But his post-playing career was shattered when he was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1998. Ten months later, he passed away at the age of 45 on Sept. 30, 1998.

In an era where velocity is king, today’s game might not have had room for Dan Quisenberry. But the numbers he compiled still shine bright through the game’s long history.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum