- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1986 Topps Pedro Guerrero

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Pedro Guerrero

In the offensively-challenged decade of the 1980s, only two National Leaguers had as many as six batting title-qualified seasons with a .300 batting average.

One was Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn. The other was Pedro Guerrero.

A lifetime .300 hitter over 15 big league seasons, Guerrero emerged from the sugar cane fields of the Dominican Republic to become one of the best all-around hitters of his era.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

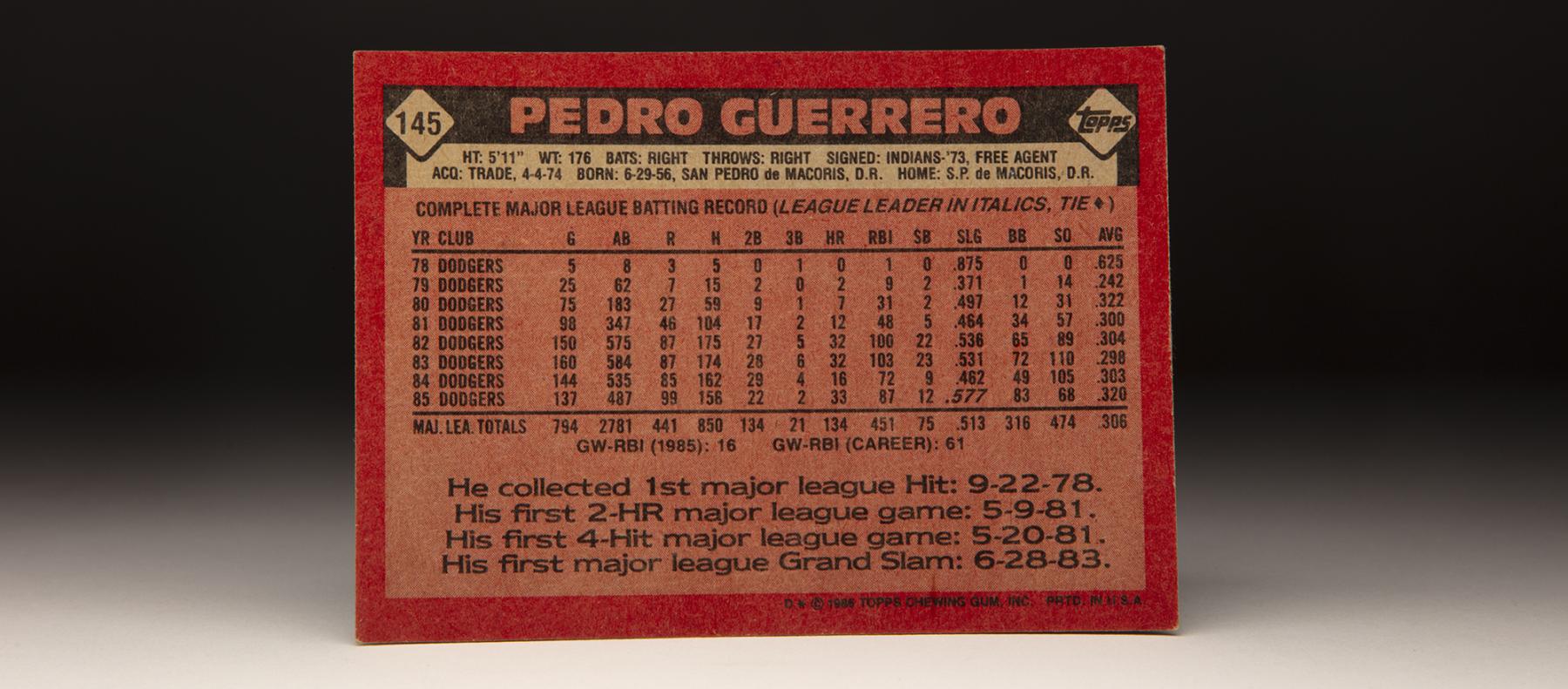

Born June 29, 1956, in San Pedro de Macoris, Guerrero worked to support his family from a young age while honing his skills on the local diamonds. San Pedro would become known as the cradle of shortstops, but the 5-foot-11, thickly-muscled Guerrero didn’t fit that mold. Instead, with line drives ringing off his bat but his position in the field still in flux, Guerrero was signed by Indians scout Reggie Otero in 1973 at the age of 16.

The Indians sent Guerrero – who spoke virtually no English – to their Gulf Coast League team in Sarasota, Fla., where he hit .255 in 44 games.

“I had a really bad time,” Guerrero told the Los Angeles Times. “I’d never been away from home before. I used to cry every day.”

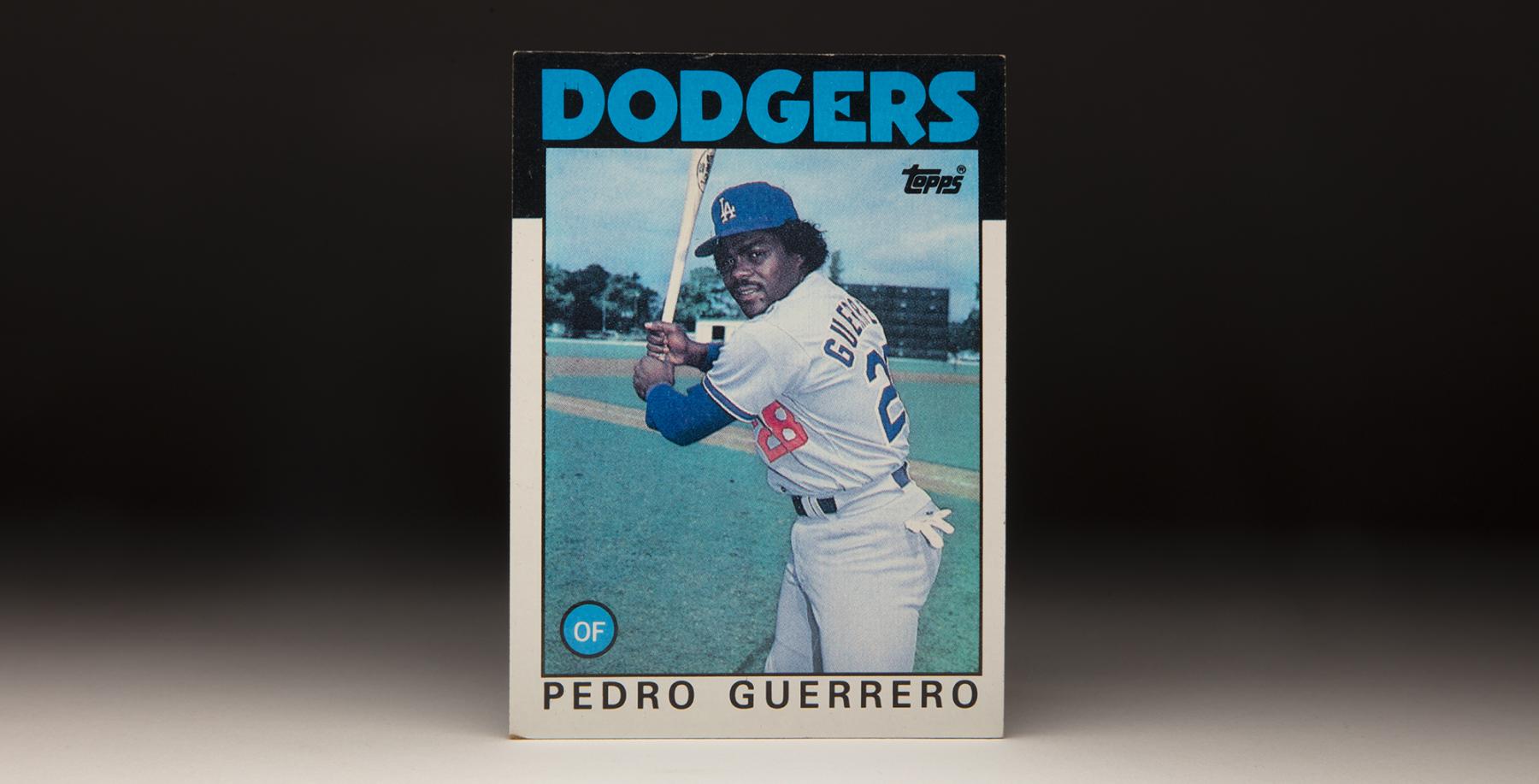

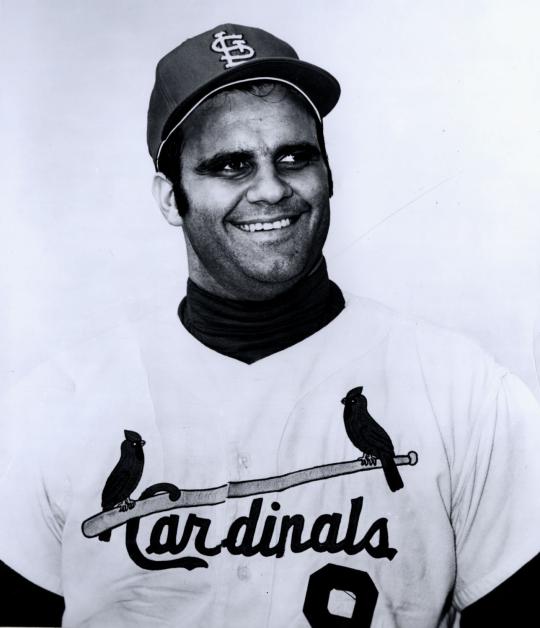

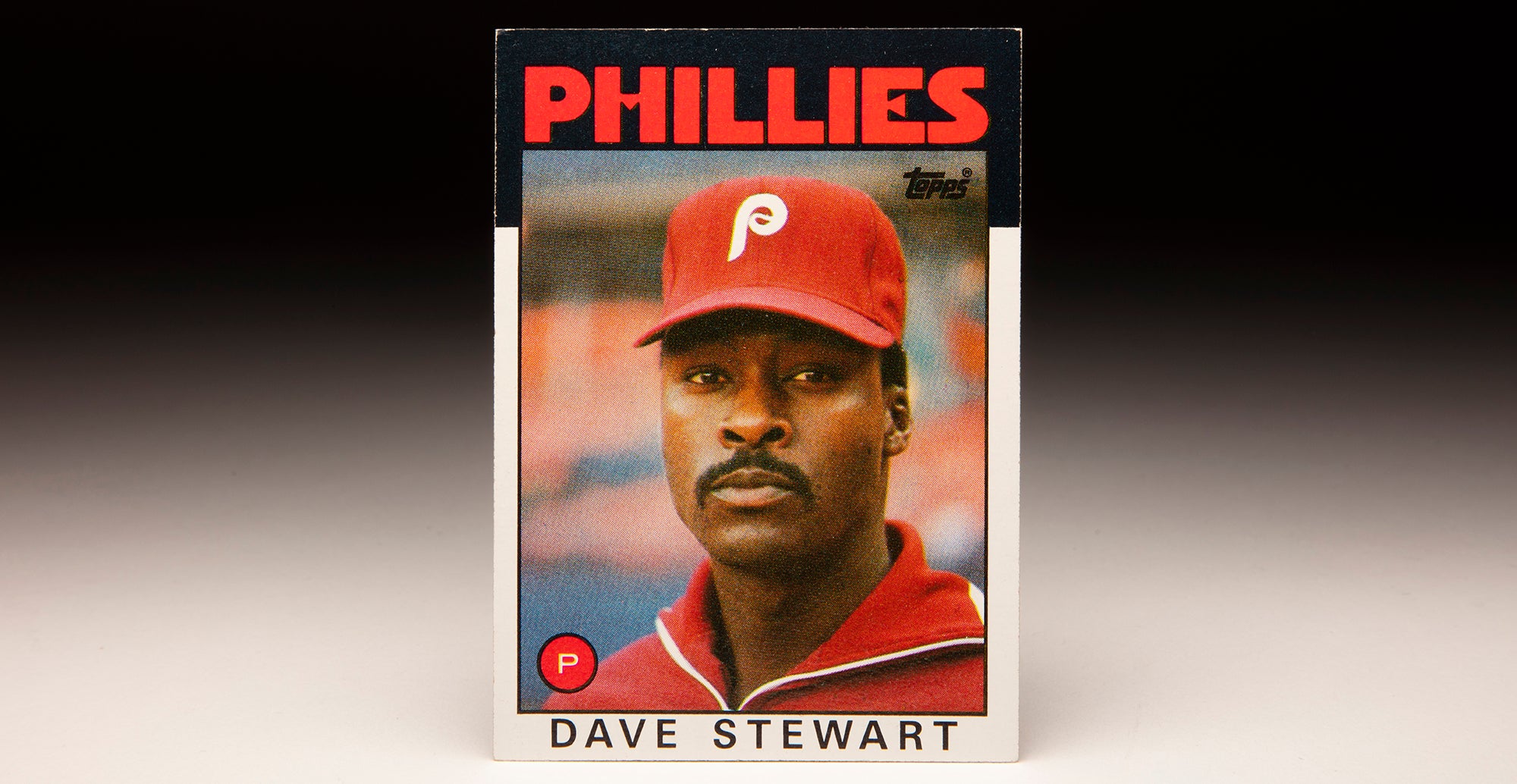

Pedro Guerrero's 1986 Topps card depicts him in a Los Angeles Dodgers uniform. Guerrero spent the first 11 years of his major league career with L.A., amassing four All-Star selections. (Topps baseball card photographed by Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

But Guerrero slowly assimilated into his new home, and by the spring of 1974 he was ticketed for Class A ball. But on April 3, the Indians traded Guerrero to the Dodgers in a straight-up deal for pitcher Bruce Ellingsen, who had been a 63rd round draft choice in 1967.

Ellingsen went 1-1 in 16 games with Cleveland in 1974 and never pitched in the majors again. Guerrero, meanwhile, was on his way to stardom.

Otero, who had left the Indians to join the Dodgers’ organization, told his new bosses to get Guerrero if they could. Guerrero made Otero look good by hitting .290 in two stops in Class A in 1974, then hit .345 with 10 homers and 76 RBI for Class A Danville of the Midwest League in 1975.

By 1977, Guerrero was with Triple-A Albuquerque, where he was hitting .403 through 32 games when a fractured ankle ended his season. He returned to Albuquerque in 1978, hitting .337 with 14 homers, 116 RBI and 17 stolen bases – earning a call-up to the big leagues in September, where he totaled five hits in eight at-bats.

The Dodgers, however, had no room on their veteran roster – and sent Guerrero back to Triple-A for a third season in 1979. There he hit .333 with 22 homers, 103 RBI and 26 stolen bases in 113 games before getting regular at-bats in the outfield and at first base for the Dodgers in September.

“I thought I was ready to play in the big leagues in ’79,” Guerrero said. “I thought I was ready to play in the big leagues in ’78.”

With Guerrero out of minor league options in 1980, the Dodgers kept their prodigy on the roster as a bench player. In 75 games – mostly in the outfield and as a pinch hitter – Guerrero hit .322 with seven homers and 31 RBI.

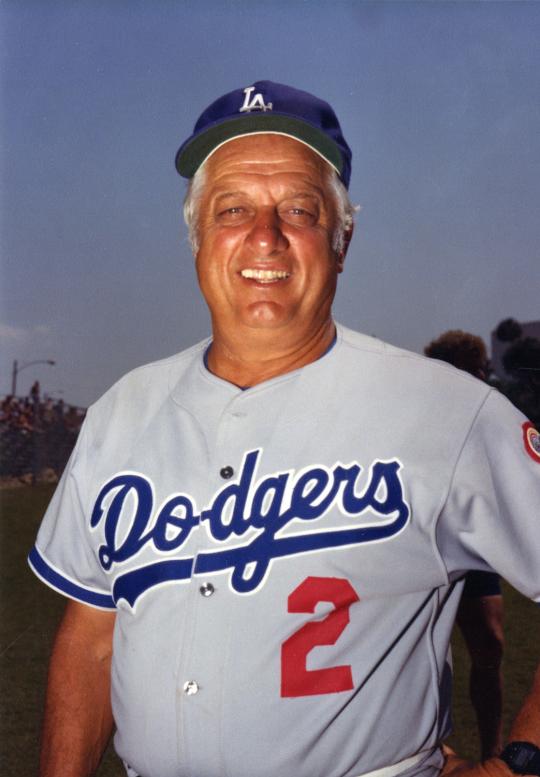

Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda compared Guerrero – who found himself in center field for much of the month of August in 1980 – to a young Willie Mays.

“Sometimes trying to live up to those expectations gets tough,” Lasorda told the L.A. Times. “But Pete Guerrero will be, within a short time, one of the most renowned players in the major leagues.”

In the spring of 1981 – with veteran Reggie Smith injured – Guerrero earned the Dodgers’ starting job in right field. He was hitting .325 with 10 homers and 30 RBI in 53 games when the strike interrupted the season – good enough to earn an All-Star Game appearance when the campaign resumed in August.

Guerrero finished the year with a .300 batting average, 12 home runs and 48 RBI. He hit a combined .139 with two homers and three RBI in the NLDS and NLCS, but the Dodgers won both rounds to advance to the World Series. Then in the Fall Classic against the Yankees, Guerrero stepped onto the national stage and put on a show.

In Game 3, his fifth-inning double tied the score and led to Mike Scioscia’s run-scoring double play that gave the Dodgers a 5-4 win to cut New York’s lead to 2-games-to-1.

Guerrero had two more hits in Game 4 as Los Angeles evened the series with an 8-7 victory. Then in Game 5, Guerrero came to the plate with one out in the bottom of the seventh with the Yankees leading 1-0 behind ace Ron Guidry, who had allowed two hits to that point. Guerrero belted an 0-1 Guidry pitch for a home run, and Steve Yeager followed with another homer to give the Dodgers a 2-1 lead that they would not relinquish.

Game 6 was a rout, with the Dodgers winning 9-2 behind three more hits and five RBI by Guerrero, who was named co-MVP along with teammates Yeager and Ron Cey.

“This,” Guerrero told the Associated Press after Game 6, “is heaven.”

But Guerrero was just getting started in his ascent to the game’s highest levels.

In 1982, Guerrero was installed as the Dodgers’ cleanup hitter and hit .304 with 32 home runs, 100 RBI and 22 stolen bases en route to a third-place finish in the National League Most Valuable Player voting. Guerrero posted strikingly similar numbers in 1983 despite being moved from right field to third base, where he struggled defensively while being charged with an NL-leading 30 errors. But at the plate, Guerrero hit .298 with 32 homers, 103 RBI and 23 steals to lead the Dodgers to the NL West crown. He even shook off a Sept. 15 beaning by Astros fastballer Nolan Ryan, remaining in the game and later asking Ryan to autograph the cracked batting helmet.

Los Angeles lost the NLCS to the Phillies in four games, but the Dodgers rewarded Guerrero on Feb. 20, 1984, with a five-year, $7 million contract – the largest deal in team history.

“His mind is at ease now,” Dodgers vice president Al Campanis told the Los Angeles Times. “With this contract, he has serenity.”

But the pressure of the new contract may have affected Guerrero, who was hitting just .240 as late as June 4 before rallying – especially after the Dodgers moved him back to right field in July – to finish with a .303 batting average to go with 16 homers and 72 RBI.

The Dodgers sent Guerrero back to third base to start the 1985 campaign, and once again Guerrero slumped. Hitting .268 on May 31, Guerrero was returned to the outfield – where he got as hot as the L.A. summer. He belted 15 homers in June and followed that with a torrid .460 batting average in July, finishing the season with a .320 average and NL-best averages for on-base percentage (.422) and slugging percentage (.577). From July 23-26, Guerrero reached base in 14 straight plate appearances, two short of the big league record set by Ted Williams in 1957.

The Dodgers returned to the top of the NL West standings, but fell to the Cardinals in the NLCS.

Then in 1986, Guerrero tore his patella tendon in his left knee while trying to steal third base in an exhibition game four days before Opening Day. The surgery sidelined him until Aug. 1.

“It’s a terrible, terrible thing,” Lasorda told the AP. “Pedro means so much for our ball club.”

In 31 games that season, Guerrero hit .246 with five homers and 10 RBI. But he came all the way back in 1987, hitting .338 with a career-best 184 hits while smashing 27 home runs to go with 89 RBI. He was named the Comeback Player of the Year by United Press International.

Entering the final year of his contract, Guerrero and the Dodgers were at a crossroads. The team had signed free agent Kirk Gibson in the offseason, injecting a no-nonsense attitude into a veteran clubhouse. But the Dodgers began the season with inconsistent play, and things boiled over on May 22 when Guerrero threw his bat at Mets pitcher David Cone – it missed Cone completely – after being hit with a slow curveball.

Guerrero received a four-game suspension and a $1,000 fine from National League president Bart Giamatti.

“I don’t care what he hit me with. It was a curveball, so what?” Guerrero told the L.A. Times. “They have all the advantages, pitchers do. They can hit the hitters and nothing happens.”

The incident, however, seemed to spark the Dodgers as the team won seven of its next 10 games and – against all expectations – remained in contention for the NL West title throughout the summer. On Aug. 16, the Dodgers – in need of starting pitching help to support the historic season being authored by Orel Hershiser – sent Guerrero to the Cardinals in exchange for John Tudor.

“I love Pete, but we needed a left-handed pitcher,” Lasorda told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “You have to give up something to get something.”

Tudor went 4-3 with a 2.41 over nine starts with the Dodgers, helping Los Angeles advance to the World Series – where the Dodgers beat the Athletics behind Gibson’s legendary pinch-hit home run in Game 1. Guerrero, meanwhile, received a three-year, $6.2 million contract extension from the Cardinals.

Guerrero was 32 at the start of the 1989 season and had chronic problems with his knees and back. But safely ensconced at first base, Guerrero appeared in all 162 games – including 160 at first – and hit .311 with a .391 on-base percentage, an NL-best 42 doubles, 17 home runs and 117 RBI. He also went more than 40 games without an error in the field. For the third time in his career, Guerrero finished third in the NL MVP voting.

“He’s the most consistent right-handed batter I’ve had the opportunity to play around,” Cardinals shortstop Ozzie Smith told the Associated Press.

Guerrero began to show his age in 1990, hitting .281 with 13 homers and 80 RBI in 136 games. On Aug. 16, Guerrero became enraged at Houston pitcher Danny Darwin after some inside pitches and punched Darwin in the mouth after Darwin reached first base the following inning, drawing a one-game suspension and a $1,000 fine.

Then in 1991, Guerrero was hitting .284 with 53 RBI on July 7 when he fractured his leg in a collision with Cardinals catcher Tom Pagnozzi, sending him to the disabled list for six weeks. He hit just .246 after returning and finished the season with a .272 average and 70 RBI in 115 games.

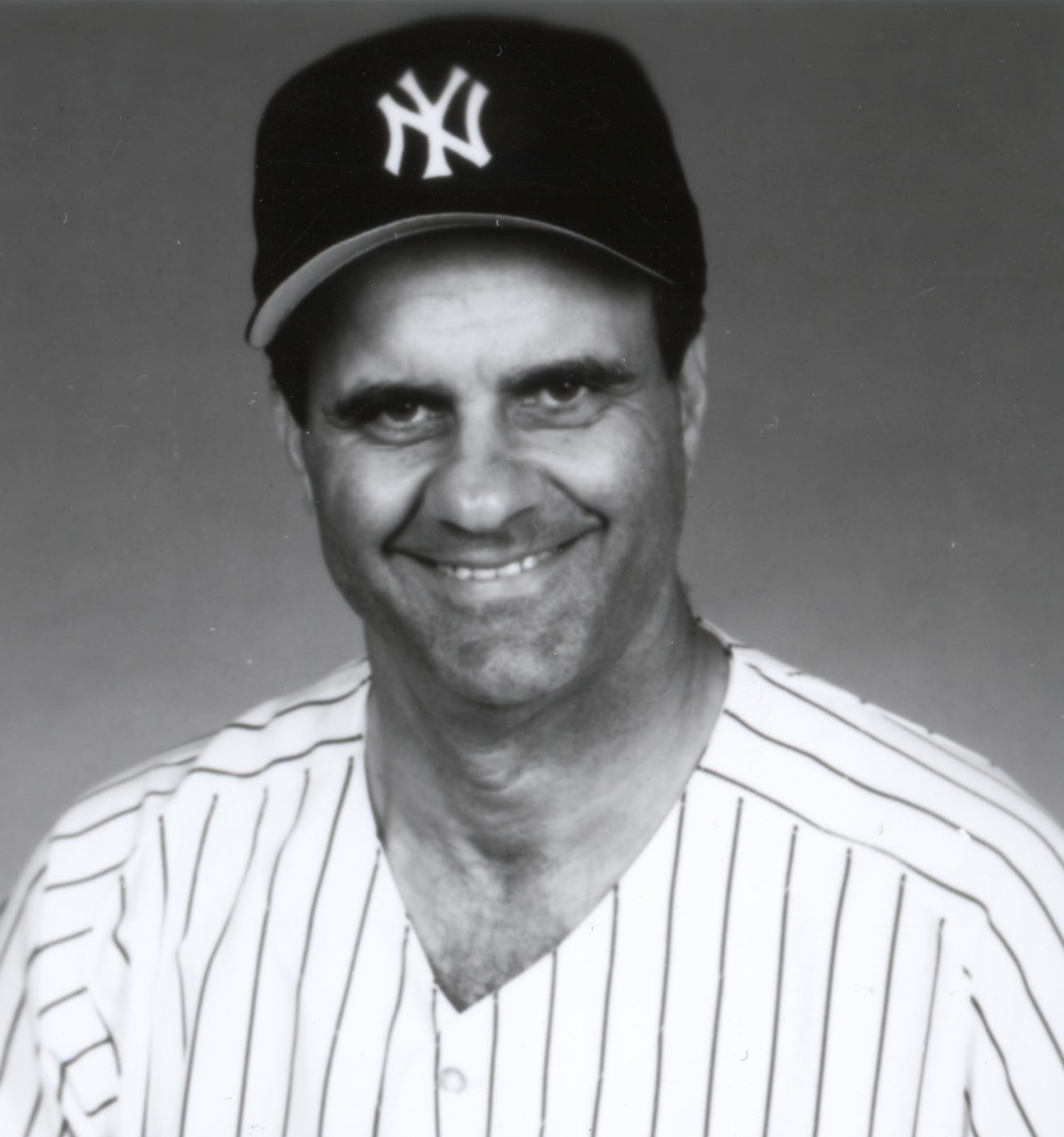

“Pete is a throwback,” Cardinals manager Joe Torre told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He has his fun, but he really wants to play. He’s got a lot of pride.”

Guerrero’s contract expired after the season, but the Cardinals brought him back despite acquiring Andrés Galarraga to play first base. Sent to left field to start the season, Guerrero was quickly relegated to a bench role. A shoulder injury limited to 43 games and a .219 batting average.

Finding no offers in the big leagues, Guerrero played in the Mexican League and with the independent Sioux Falls Canaries in 1993, returned to the Canaries in 1994 and then appeared in 66 games with the Angels’ Double-A team in Midland, Texas, in 1995 before retiring.

Guerrero was arrested on cocaine conspiracy charges in 1999 – charges for which he was later acquitted. He went on to manage in the Mexican League.

Guerrero suffered a stroke in 2015 and another one in 2017 – the latter leaving him in a condition where doctors briefly declared him brain dead. But Guerrero recovered from each emergency.

He finished his big league career with 1,618 hits, 267 doubles, 215 home runs, 898 RBI, a .370 on-base percentage and five All-Star Game selections.

At his peak, few National Leaguers were considered more complete hitters.

“He’s got power in any yard,” said Cardinals pitcher Danny Cox when Guerrero was dealt to St. Louis. “And not only does he hit for power, he hits for average.

“If you make a mistake, he’s going to make you pay for it.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum