- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1986 Topps Buddy Bell

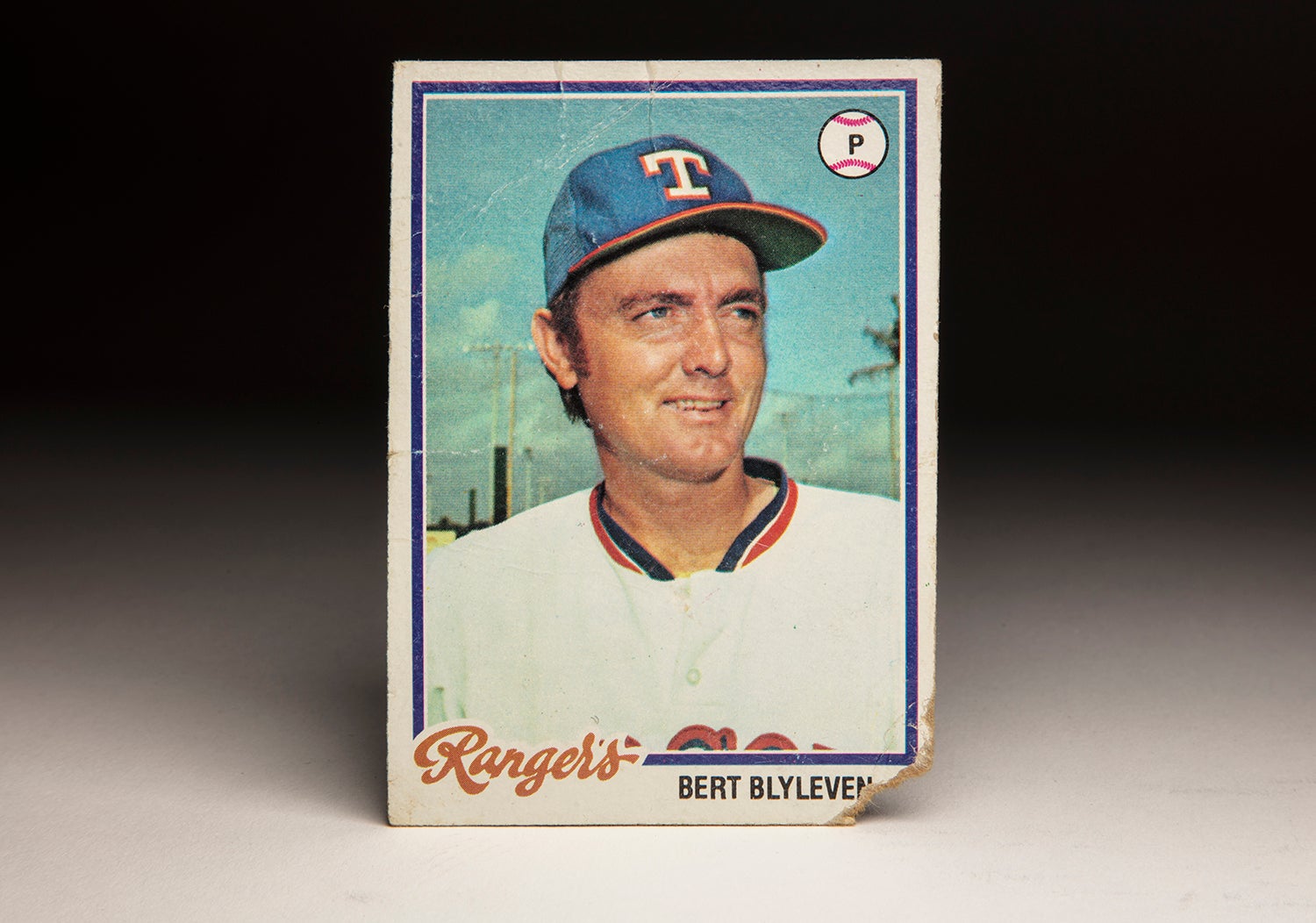

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Buddy Bell

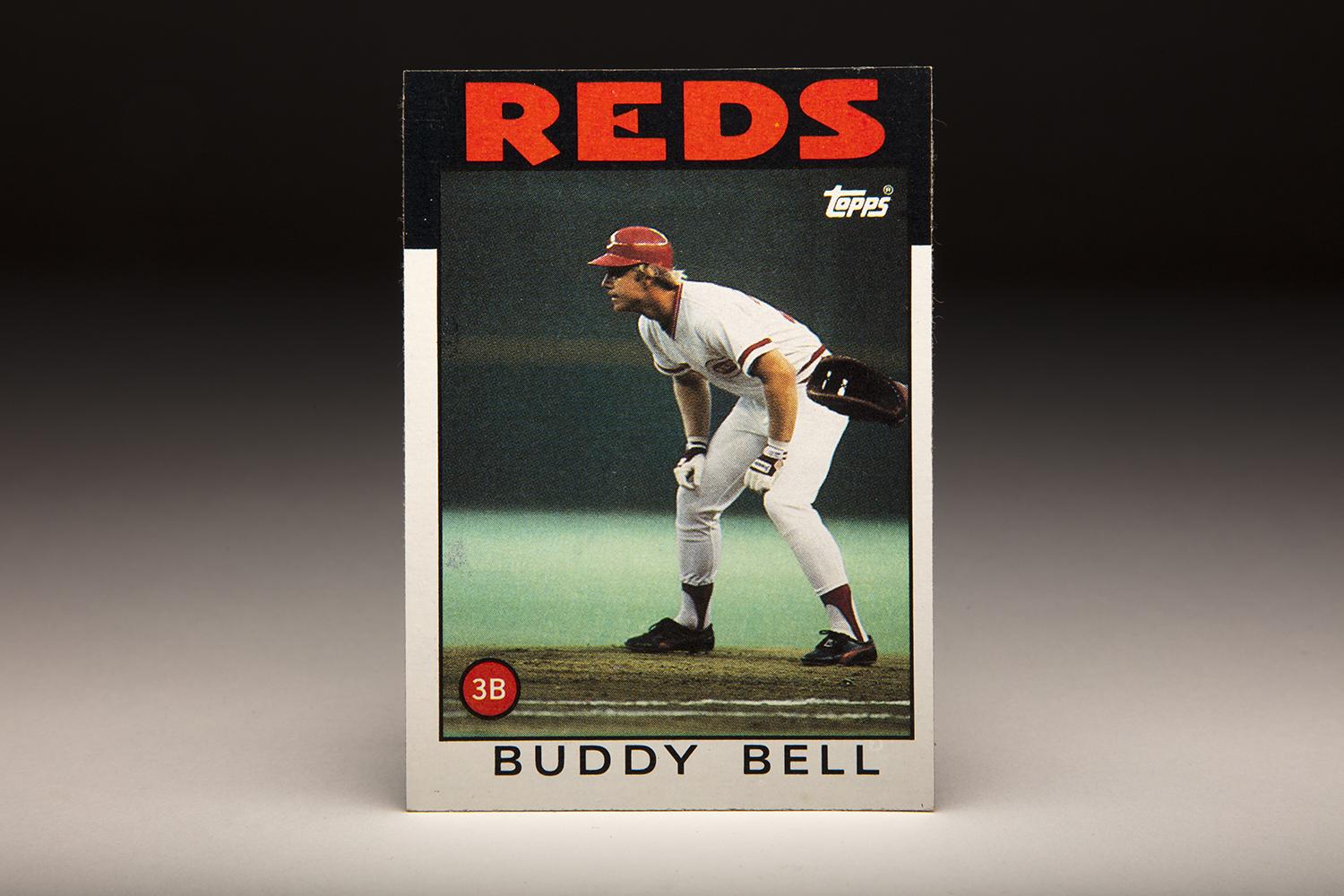

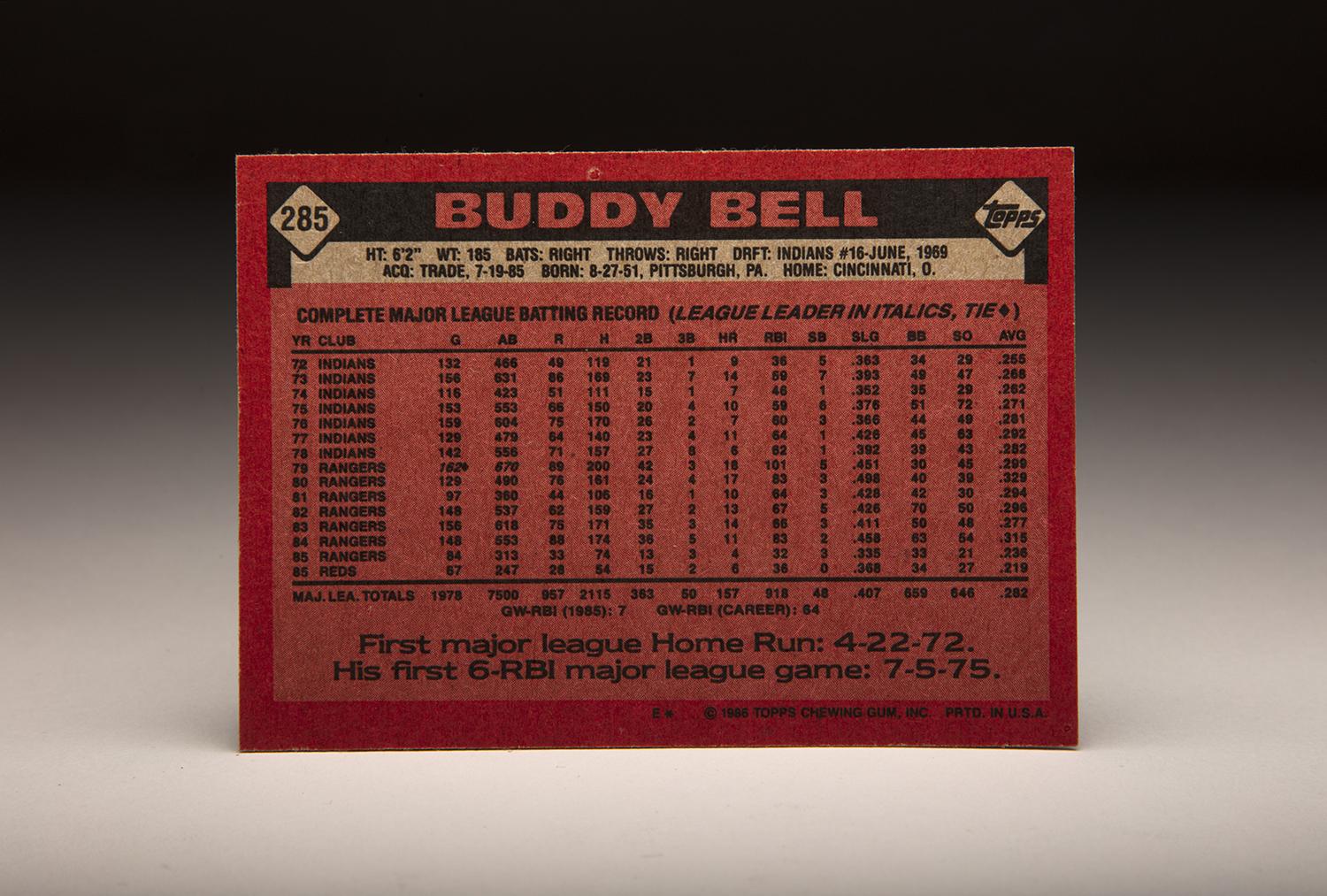

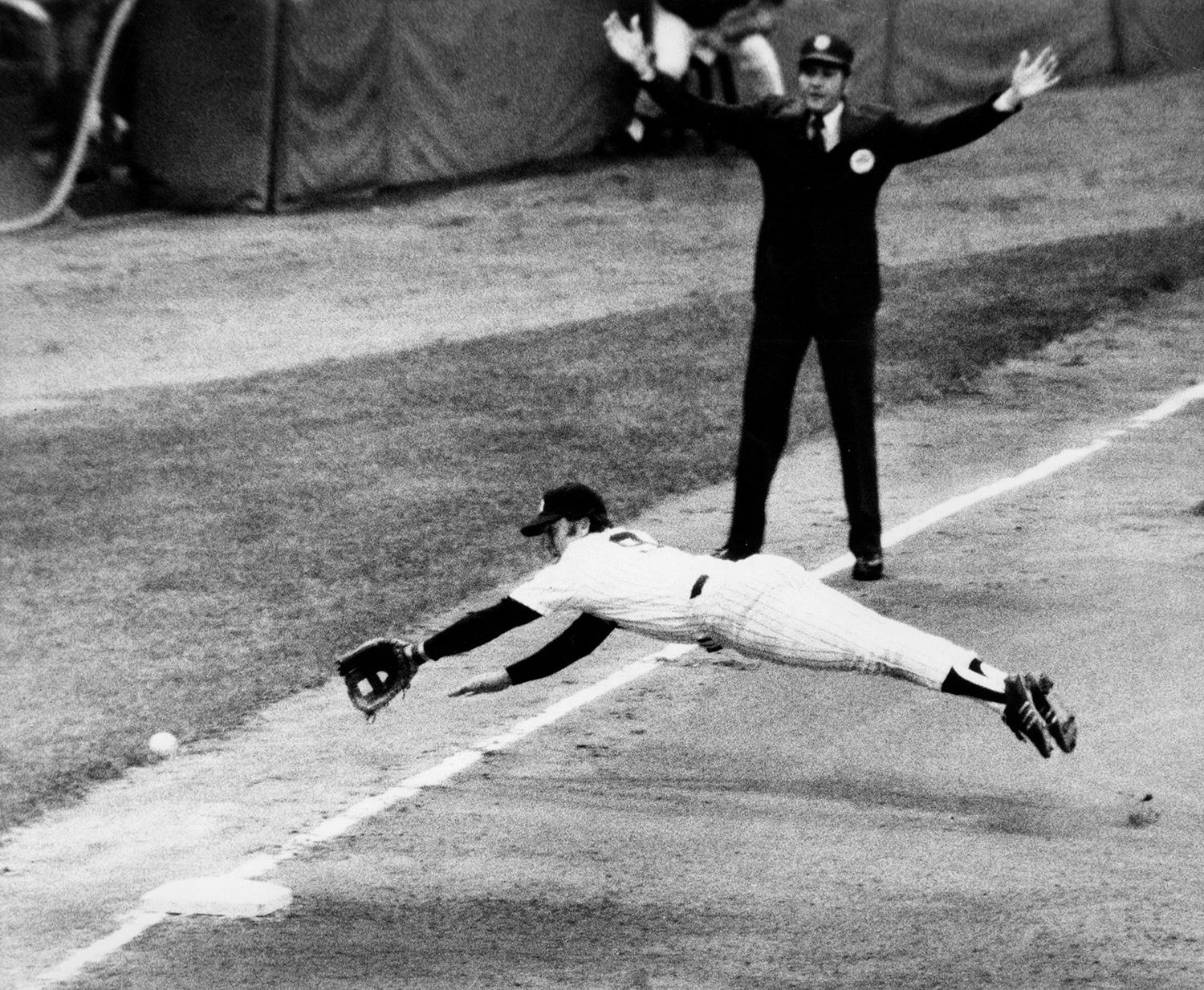

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown. With its 1986 set, the Topps Company made an unusual choice. Rather than resurrect its popular black-bordered design from 1971, Topps opted for a compromise: A black border near the top of the card, with the rest of the card framed in the standard white. Some card collectors would have preferred the all-black border, but I suppose Topps was reluctant to do that because of the way that black borders tend to “chip” or “flake,” showing even the slightest bit of imperfection. Such cards are nearly impossible to maintain in mint condition, even if the black border does give the card a unique and striking appearance. So rather than go full bore with a 100 percent black border, Topps adopted the two-tone look, for better and worse. While I have mixed feelings about the 1986 set, I have no misgivings about the card depicting David Gus Bell, AKA Buddy Bell. It’s one of the best cards in the set, a nicely done action shot that shows Bell leading off of first base in a game at the old Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. There’s also a little bit of mystery to the card. Is this a night game, or a day game? That’s hard to tell. And who is the first baseman holding him on? All we can see is a left-handed first baseman’s mitt to the right of Bell, so it could be anyone from Keith Hernandez (Mets) to Sid Bream (Pirates) to Will Clark (Giants).

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Then again, it doesn’t really matter who the first baseman is, since it’s Bell who is the intended subject matter of the card. As we can see in the photograph, Bell was a player who always wore his uniform correctly, with just the right amount of red stirrup showing, and his pants and jersey neither too baggy nor too tight. To me, Bell always looked like the epitome of a ballplayer; strongly built at six feet, one inches and 180 pounds, he was not too thin, but not an ounce overweight either. Some players just carry themselves the way that a major league ballplayer should. One of those players was Ken Singleton. Bell was another.

Whether at bat, in the field, or on the bases, Bell always appeared balanced and sure of himself. On this card, we see him staring in toward home plate, keeping himself fully aware of the batter (and probably the pitcher, too).

Bell did more than just put up a good appearance, however. An old school player, he always hustled. At one point, he played with a fracture in his leg. His steely determination drew him respect in every clubhouse that he played in, from Cleveland to Texas to Cincinnati to Houston.

By 1986, when his Topps card came out, Bell was nearing the end of his long career. Still, he remained a productive player that summer. His professional journey had begun more than 15 years earlier, when the Cleveland Indians signed the precocious middle infielder at the age of 17.

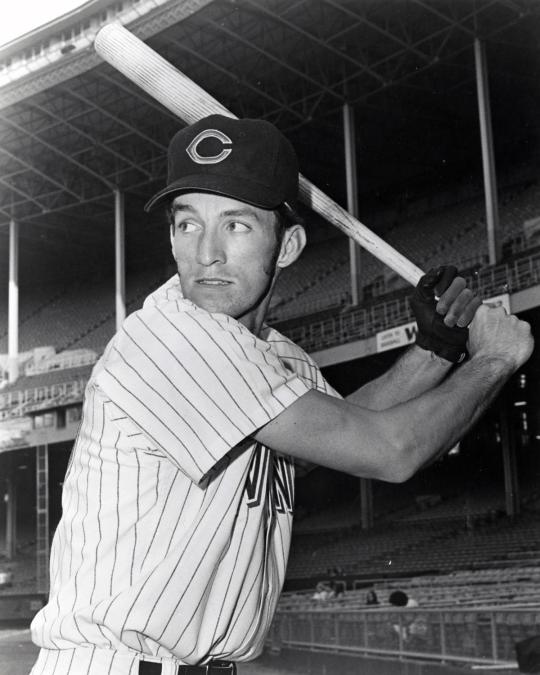

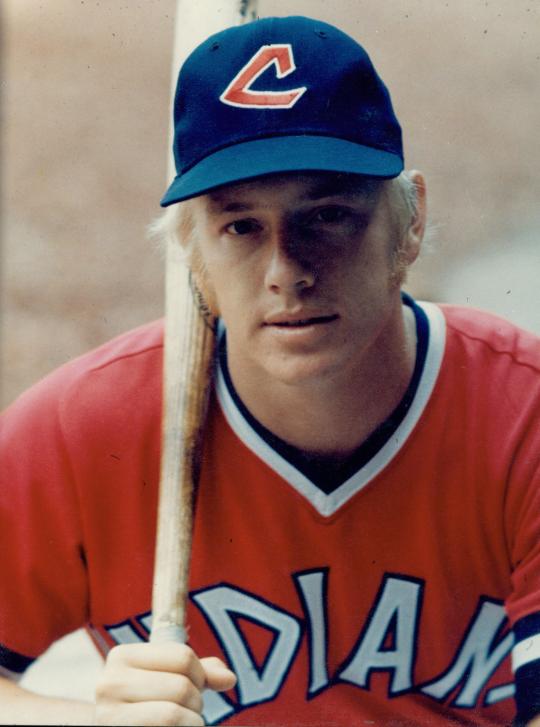

Bell was already someone of brand-name quality. As the son of former Cincinnati Reds slugger Gus Bell, Buddy’s pedigree made it even more tempting to sign him. Drafting Bell out of Cincinnati’s Moeller High School in 1969, the Indians assigned him to their Rookie League affiliate in the Gulf Coast League. Not surprisingly, the teenager struggled, hitting only .229 with little power. He also played second base, a position that would eventually become foreign to him in the major leagues.

With some valuable pro experience under his belt, Bell began to shine in 1970. The Indians moved him up to Class A ball, where he responded with 12 home runs and a .265 batting average. Even though his numbers were not overwhelming, the Indians felt that he could bypass Double-A ball in 1971 and move all the way up to Triple-A Wichita of the American Association. The Indians also changed his position, moving him from second base, where he appeared a step slow, and making him into a third baseman. Bell initially struggled with the demands of third base, posting a fielding percentage of just over .900. But he more than held his own facing pitchers much older than him, as he batted .289 with 11 home runs.

In 1972, the 20-year-old Bell reported to the Indians’ Spring Training camp in Arizona. Given his youth and his general lack of experience, it seemed reasonable to expect that the Indians would send him back to Triple-A for some additional preparation. In fact, with two weeks to go in Spring Training, Bell had yet to appear in an exhibition game. One afternoon, Bell received news that the Indians, who were playing in Yuma, needed a replacement for injured outfielder John Lowenstein. Bell took a late bus to Yuma, played right field, picked up four hits in five at-bats, and drove home the game-winning run. From then on, Bell remained in the starting lineup, continued to hit, and earned himself a spot on the Opening Day roster.

Needing help in the outfield, the Indians used Bell mostly as a center fielder and right fielder. With third base already occupied by Graig Nettles, the Indians felt that the outfield offered a decent alternative for Bell. “It was kind of strange, playing the outfield,” Bell told sportswriter Joe Quinn, “but Graig Nettles was playing third base and I was happy to be playing anywhere.”

Bell played regularly for the Indians that summer, appearing in 132 games, but he did not hit well. With a .255 batting average and an OPS of .672, Bell’s struggles made some observers wonder if the Indians would have been better served sending him back to the minor leagues.

Prior to the 1973 season, the Indians made a wise move with Bell. They didn’t send him back to Triple-A, but they did move him from the outfield, where he lacked footspeed, to third base, a position that relies more on footing and quickness. To accommodate the move, the Indians traded Nettles to the New York Yankees as part of a blockbuster deal. Bell would commit 22 errors at the new position, but showed good range and also blossomed as a hitter. Batting .268 with 14 home runs and 49 walks, Bell became a contributor on offense. He also made the American League All-Star team, making him part of the first father-and-son combination to earn All-Star Game selections.

Over the next five seasons, Bell alternated down seasons with more productive ones. He didn’t hit with much power, but his batting average improved over a three-year span and he evolved into a near magician at third base. With his plus range, sure hands, and strong throwing arm, Bell emerged as one of the league’s best defensive third basemen, along with Nettles, Brooks Robinson and Aurelio Rodriguez. Bell drew strong praise from Nettles himself. At one point, Nettles told the Cincinnati Enquirer, “He’s as good a third baseman as I’ve ever seen.”

Bell played solidly for the Indians, but they wanted more power from the hot corner. After the 1978 season, Bell heard that the Indians might trade him to Cincinnati, his hometown. Bell told reporters that a trade to Cincinnati would have thrilled him, but the Indians chose a different trade partner. They dealt Bell to the Texas Rangers for Toby Harrah, who hit more home runs and drew more walks than Bell, but did not play third base with the same kind of skill as his predecessor.

The Rangers hoped that Bell would benefit from playing at Arlington Stadium, a ballpark where fly balls traveled well. In his first season with Texas, Bell hit 18 home runs – a career high. He also drove in 101 runs, batted .299, took home his first Gold Glove Award, and finished 10th in the league MVP voting. He also showed durability, playing all 162 games, a remarkable achievement given the heat and humidity of Arlington.

Bell would play even better in 1980, raising his batting average to .329 and his OPS to .877. The trend of fine play would continue over the next three seasons. By the end of his six-year tenure in Texas, Bell had won six Gold Glove Awards, made four All-Star teams and received MVP consideration five times. From 1979 to 1984, Bell and Kansas City’s George Brett represented the two best third baseman in the American League.

A slow start to the 1985 season finally signaled a change for Bell. He was now 33, and the Rangers suspected that he was ready to fall into a steep decline. So in mid-July, they traded him to Cincinnati for two younger players, outfielder Duane Walker and reliever Jeff Russell.

In so many ways, it seemed right for Bell to play for Cincinnati. The Reds were the same team that his father, Gus, had played with from 1953 to 1961. Gus’ popularity in Cincinnati paved the way for a warm reception for Buddy, who was also born and raised in Cincinnati. In making Bell their third baseman, the Reds stabilized a position that had become a problem since Ray Knight’s time there in the late 1970s.

The move from Arlington to Cincinnati thrilled Bell. “Waiting for the trade to go through was the most nervous I’ve been for a long time,” Bell told famed sportswriter Hal McCoy. “My father and my mother and my friends and my relatives can watch me play… It wish it could have happened a few years ago. I can’t wait to get on the field to help the Reds win.”

Coming home can be difficult, too. Bell struggled in his immediate transition to the National League, batting only .219 over the balance of the season. But he bounced back remarkably in 1986, reaching career highs in home runs (20) and walks (73). Even at the age of 34 and playing on the hardened turf of Riverfront Stadium, he showed an unusual level of durability by appearing in 155 games.

After another good season in 1987, Bell finally began to show some cracks by 1988. A bad start to the season convinced the Reds it was time to move on, so they traded him to the Houston Astros for proverbial player to be named later. Unimpressed by his second-half play, the Astros released him in December. That allowed him to forge a reunion with the Rangers, who signed him to serve as a platoon DH. Bell played sparingly for the Rangers in 1989 before announcing his retirement in June.

Shortly after his playing days, Bell moved into coaching. He became a minor league instructor with the Chicago White Sox before returning to the Indians as an on-field coach in 1994 and ’95, While with Cleveland, Bell drew the attention of the Detroit Tigers, who needed a new manager after the retirement of Sparky Anderson. The Tigers offered Bell the job, a mixed blessing of sorts. On the one hand, Bell was thrilled to have a chance to manage at the highest level. On the other hand, the Tigers had the talent level of an expansion team. Saddled with one of the worst pitching staffs of the last 25 years, Bell suffered through a 59-win campaign, with the Tigers drawing comparisons to the inaugural New York Mets of 1962. Miraculously, the Tigers rebounded to win 79 games in 1997, but they regressed in 1998, costing Bell his job.

Bell resurfaced as a manager with the Colorado Rockies in 2001, the team performing decently for two seasons. A poor start to 2002 doomed Bell to the firing line again, but he did receive another chance when the Kansas City Royals came calling during the 2005 season. That last stint turned into a disaster, as the Royals won only 39 percent of their games over the next two and a half seasons. Bell received his share of criticism from the media and fans, some of whom pointed to his earlier struggles in Detroit and Denver. Bells’ critics claimed that he was too rigid in his ways, and out of touch with the modern day player. Then again, the Royals had assembled the worst record in baseball prior to Bell’s arrival, so it was unfair to pin all of the blame on the manager.

During his latter days in Kansas City, Bell’s situation became more difficult when he was diagnosed with a growth on his tonsils. Although doctors were able to treat the cancerous growth, Bell decided that it was time to resign so that he could spend more time with his family. Given his health, Bell returned to the White Sox in an off-the-field role; he has worked in Chicago’s front office ever since.

Bell not only remains active within the game, but he has seen his legacy advanced through his sons. Both David and Mike went on to play third base in the major leagues, with David establishing a reputation as a fine fielder in his own right. The Bells have helped form a baseball rarity: a three-generation family that has found roster spots in the major leagues over the span of more than 65 years.

Buddy Bell works in relative obscurity these days, which I suppose is appropriate for a player who was so underrated for so long during his career. As Graham Womack wrote in a recent article for the Sporting News: “If Buddy Bell isn’t the most underrated player in baseball history, he isn’t terribly far off.” Womack went on to refer to the Bell as the Adrian Beltré of the 1980s, high praise indeed.

While that latter point could be debated, one other contention should not bring as much discussion or disagreement: few could wear a uniform as well as Bell. When it comes to epitomizing what a ballplayer should look like, not to mention approaching the game like an old school professional, Buddy Bell remains near the top of the list.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame