- Home

- Our Stories

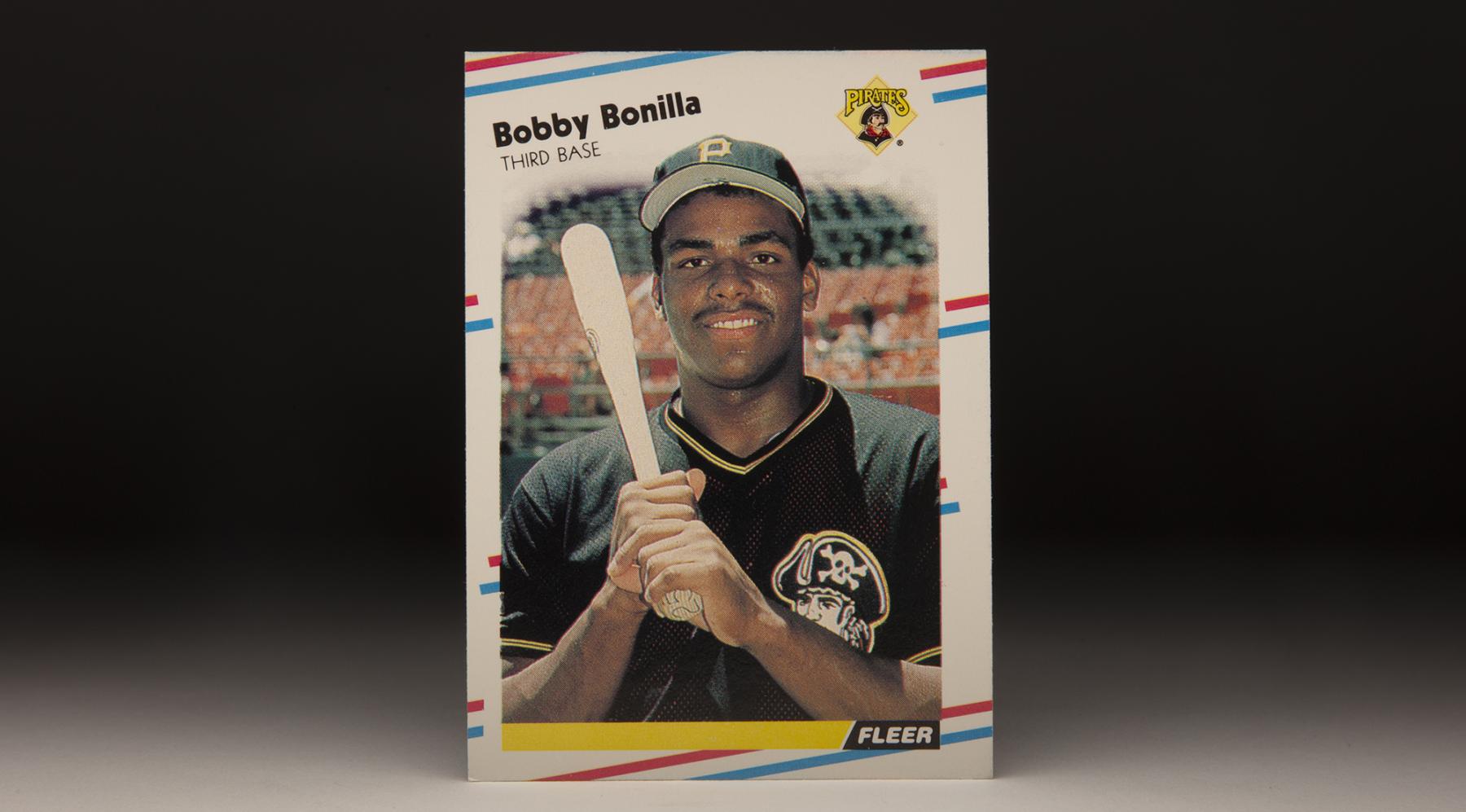

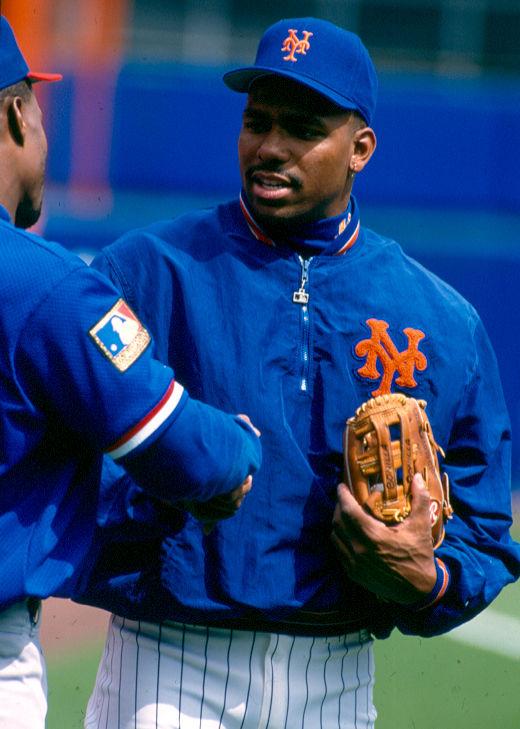

- #CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Bobby Bonilla

#CardCorner: 1988 Fleer Bobby Bonilla

Bobby Bonilla began his career in the shadow of Barry Bonds and ended it with a contract that is an annual talking point for baseball fans.

In between, the slugging kid from the South Bronx hit all the highs and lows that baseball could offer.

Born Feb. 23, 1963, Bonilla – whose parents moved to the Bronx from Puerto Rico before he was born – grew up about a mile away from Yankee Stadium and turned to sports as a way to seek a better life. Bonilla starred on the diamond in high school but went unselected when he became eligible for the MLB Draft in 1981.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

But his high school coach, Joe Levine, had other ideas when Bonilla enrolled in college with plans to study computer science. Levine arranged for Bonilla to join an all-star squad that would play ball in Europe that summer and helped Bonilla pay the costs associated with travel.

“I’m not where I am today if it wasn’t for him,” Bonilla told the Los Angeles Times in 1988.

Syd Thrift, who had helped found the Kansas City Royals Baseball Academy in the 1970s but was then working in real estate, coordinated the trip to Europe. Based on Thrift’s recommendation, the Pirates signed Bonilla on July 11, 1981, and sent him to their rookie ball affiliate in the Gulf Coast League.

Bonilla spent two nondescript seasons in rookie ball, but began to emerge as a prospect in 1983 when he scored 88 runs to go with 11 homers, 59 RBI and 28 stolen bases for the Class A Alexandria Dukes of the Carolina League.

He was promoted to Double-A in 1984, posting similar numbers with 74 runs scored, 11 homers, 71 RBI and 15 steals in the pitcher-friendly Eastern League. The Pirates invited Bonilla to their Spring Training camp in Bradenton, Fla., in 1985 – but the opportunity turned into injury when Bonilla broke a bone in his right leg after colliding with teammate Bip Roberts during a “B” game against the Kansas City Royals.

The setback limited Bonilla to 39 games at Class A Prince William (where the Alexandria franchise had moved) in 1985. Following the season, the Pirates decided not to include Bonilla on their 40-man roster – and the White Sox grabbed him in the Rule 5 Draft.

“That was an awful gamble I had nothing to do with,” said Thrift, who had become the Pirates general manager about a month before the 1985 Rule 5 Draft.

But Thrift would soon correct the team’s mistake. Bonilla got regular playing time with the White Sox at first base and left field, needing to stay on Chicago’s roster or be offered back to the Pirates. After hitting .269 with two homers and 26 RBI in 75 games, Bonilla went back to Pittsburgh when Thrift offered Jose DeLeon – a talented and often hard-luck pitcher – in a one-for-one deal that was consummated on July 26, 1986.

Though they didn’t know it at the time, the Pirates had just acquired the cleanup hitter who would lead them back to the postseason.

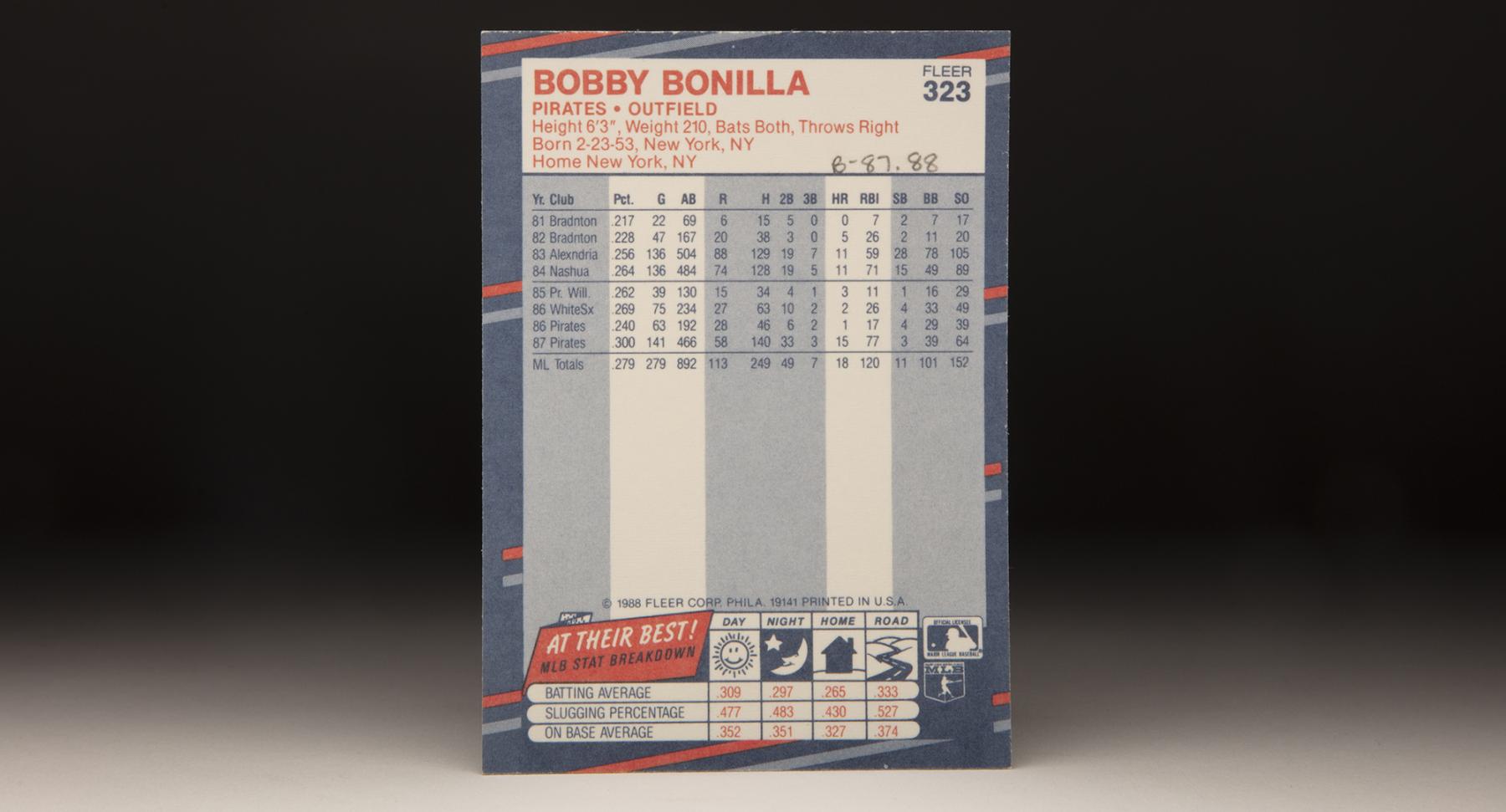

Bonilla started the 1987 season in left field before moving around the diamond until mid-June. At that point, Pirates manager Jim Leyland installed the 6-foot-3, 210-pound Bonilla at third base. Over the next three months, the switch-hitting Bonilla raised his average to .300 while finishing the season with 15 homers and 77 RBI.

“It’s what was expected of me,” Bonilla told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “They saw a little bit of it in Spring Training.

“Going to third base day-in and day-out was wonderful.”

Bonilla stepped onto the national stage the following season, playing each of his 159 games at third base while hitting 24 home runs and recording 100 RBI. He was elected as the National League’s starting third baseman in that year’s All-Star Game, the first of six times he would be named to the Mid-Summer Classic.

By the end of the season, he had become the first player in Pirates history to homer from both sides of the plate in the same game.

The Pirates regressed from 85 wins in 1988 to 74 in 1989, but Bonilla’s star continued to rise as he appeared in 163 games while batting .281 with 96 runs scored, 24 homers and 86 RBI.

Bonilla was publicly upset following the season after an arbitrator sided with the Pirates’ offer of $1.25 million for the 1990 campaign instead of the $1.7 million Bonilla sought. But those feelings were quickly brushed aside when Leyland made several key lineup changes, including moving Bonilla to right field and putting Bonds in the No. 5 spot in the batting order behind Bonilla.

The Pirates sprinted out to a 49-32 record at the All-Star break, leading the favored Mets by one-half game. They held off New York down the stretch to capture the NL East title, with Bonilla hitting 32 home runs and driving in 120 runs while scoring 112 times.

In the National League Championship Series against the Reds, however, Bonilla hit just .190 with one RBI and no runs scored over six games as Cincinnati’s power arms shut down Pittsburgh’s bats.

Bonilla finished second the NL Most Valuable Player voting, receiving the only first-place vote that Bonds – the winner – did not.

With free agency approaching after the 1991 season, Bonilla again went to arbitration and again lost – this time settling for $2.4 million. It was widely assumed that Bonilla would leave Pittsburgh as a free agent after the season.

“Scouts work a lifetime to come up with players like Bonds, Bonilla, (Andy) Van Slyke and Jose Lind,” Leyland told the Los Angeles Times. “I don’t want to lose them.”

The Pirates repeated as NL East champs in 1991, with Bonilla hitting .302 with a league-high 44 doubles, 102 runs scored, 18 home runs and 100 RBI. He also drew a career-high 90 walks – many coming early in the season while Bonds was in a protracted slump. But Bonds got hot down the stretch, and Pittsburgh coasted to a comfortable 14-game margin over the second-place Cardinals.

In the NLCS, however, the Braves pitching had their way with most of Pittsburgh’s lineup. Bonilla hit .304, but had only one RBI and two runs scored as the Pirates lost in seven games – the final two by shutouts.

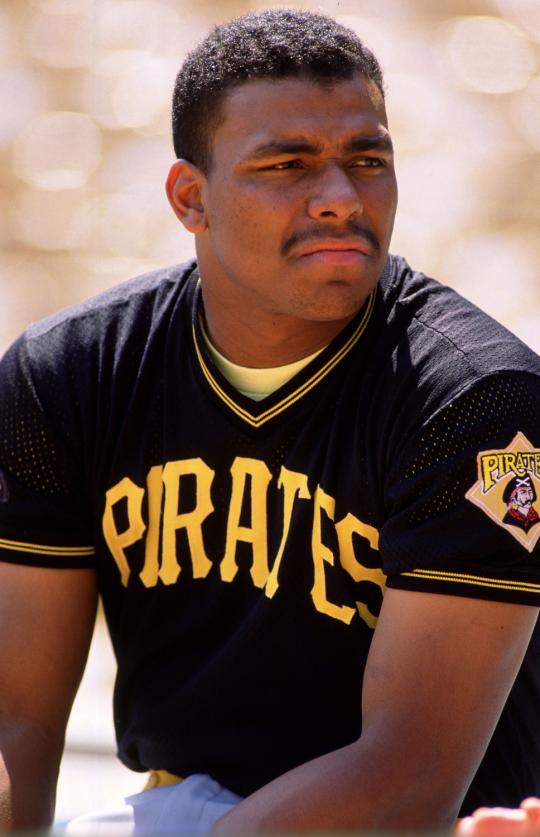

On Dec. 3, 1991, Bonilla agreed to a record-setting five-year, $29 million contract with the New York Mets.

“I’m crushed for Jim Leyland,” Bonilla told the Associated Press. “The way he treated the players was tremendous and I feel bad for what’s happening to him. But it’s a business.”

That business turned on Bonilla in 1992, when he was mired in a season-long slump before fracturing a rib in August while feuding with the media along the way. He finished the season with a .249 batting average, 19 homers and 70 RBI.

The ever-present smile he wore in Pittsburgh seemed to be gone.

Bonilla rebounded in 1993, hitting 34 home runs and driving in 87 runs for a Mets team that lost 103 games. He was hitting .290 with 20 homers and 67 RBI when the strike ended the 1994 season, then hit .325 with 18 homers and 53 RBI through 80 games in 1995 before the Mets traded him to the Orioles for Damon Buford and Alex Ochoa. He finished the campaign with a .329 average, 28 homers and 99 RBI.

In 1996, the Orioles asked Bonilla to become their designated hitter – a move Bonilla, 33 years old at the time, resisted. He eventually returned to right field, finishing the year with a .287 batting average, 28 home runs, 116 RBI and 107 runs scored as the Orioles advanced to the ALCS before falling to the Yankees. But hard feelings remained on both sides – and Bonilla left as a free agent, signing a four-year, $23.3 million contract with the Marlins, who were skippered by Jim Leyland.

“This place is a time bomb waiting to go off,” an enthusiastic Bonilla told the South Florida Sun Sentinel after signing.

Back at third base, Bonilla hit .297 with 17 homers and 96 RBI as the Marlins won the NL Wild Card before defeating the Giants in the NLDS and the Braves in the NLCS. In the World Series, Bonilla hit just .207. But his leadoff single in the bottom of the 11th inning of Game 7 sparked the rally that eventually brought the Marlins the title.

The glory in Florida was short-lived, however, as Marlins management began dismantling their championship team in one of baseball’s most famous fire sales. Bonilla was dealt to the Dodgers on May 14, 1998, as part of a seven-player deal that temporarily brought Mike Piazza to the Marlins. But Bonilla struggled in Los Angeles, hitting .237 over 72 games with seven homers and 30 RBI.

The Dodgers hired Davey Johnson as their new manager after the season – the same Davey Johnson who clashed with Bonilla in Baltimore over his resistance to become a DH.

“I figured that as soon as I heard his name (Johnson) involved out there, they would be looking to send me someplace far away,” Bonilla told the Los Angeles Times. “I didn’t have a problem with helping the team (the 1996 Orioles), my problem was with the way the whole thing was handled. I had 10 years in this game, and they knew that I’m a National League-type player. I need to be out there, and all I wanted to do was play. Then all of a sudden, it’s ‘Bobby Bo has an attitude problem.’”

On Nov. 11, 1998, the Dodgers sent Bonilla to the Mets in exchange for Mel Rojas. But Bonilla batted just .160 in 60 games in New York, and the Mets placed him on irrevocable waivers during the season – only to watch as no team claimed him.

On Jan. 3, 2000, the Mets released Bonilla – agreeing to restructure his contract, which had one year and $5.9 million remaining. The new deal guaranteed Bonilla a $1.19 million annual payment July 1 starting in 2011 and running for 25 years.

Bonilla wrapped up his career as a bench player with the Braves in 2000 and the Cardinals in 2001, helping both teams make the playoffs. He finished with a .279 batting average, 287 home runs, 408 doubles, 1,084 runs scored and 1,173 RBI.

No player whose career began in the MLB Draft era (post 1964), was eligible for the Draft and went undrafted has ever totaled more RBI.

“I’m the type who pinches himself every day,” Bonilla told the L.A. Times in 1988. “I mean, people talk about the pressure of playing in the big leagues, but where’s the pressure compared to growing up in a ghetto and looking for ways to get out? I’m talking about houses burning and people starving, and I’m supposed to be trembling playing the first place Mets…or Dodgers?

“I’m having the most fun I’ve ever had.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum