- Home

- Our Stories

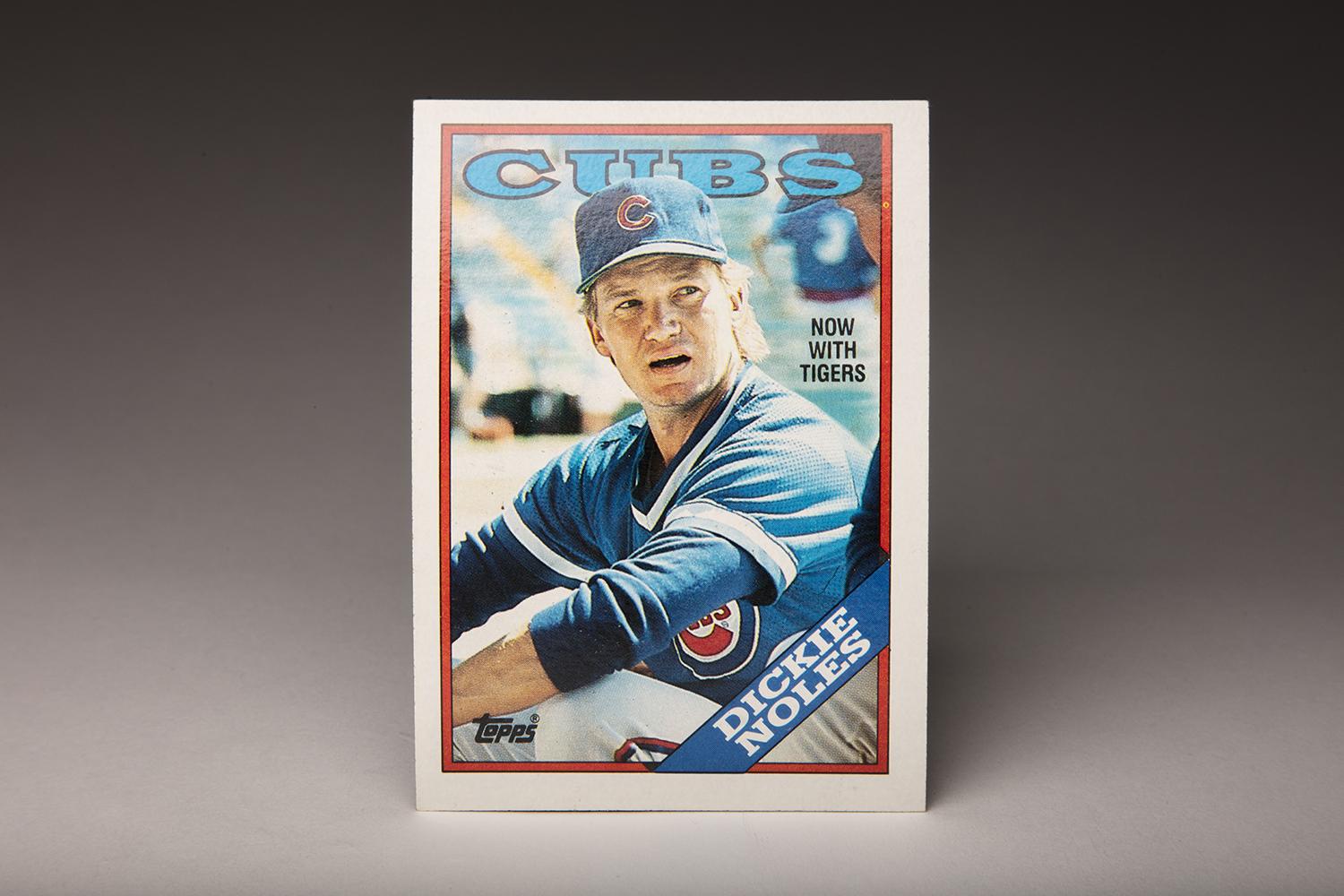

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

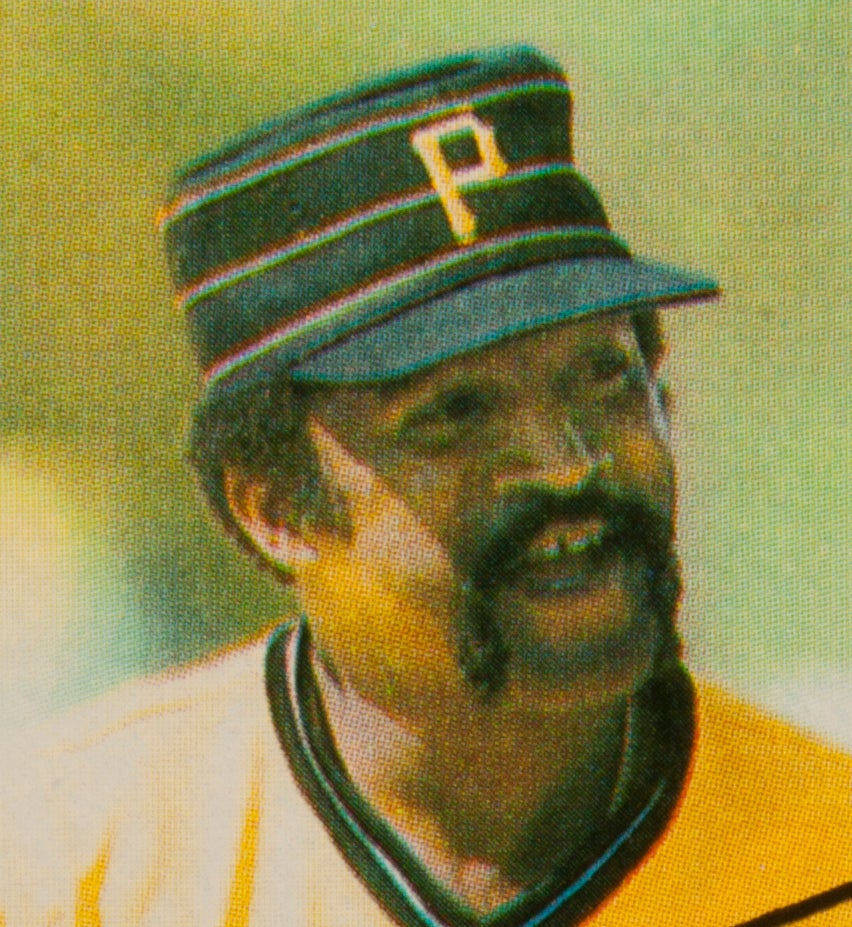

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dickie Noles

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

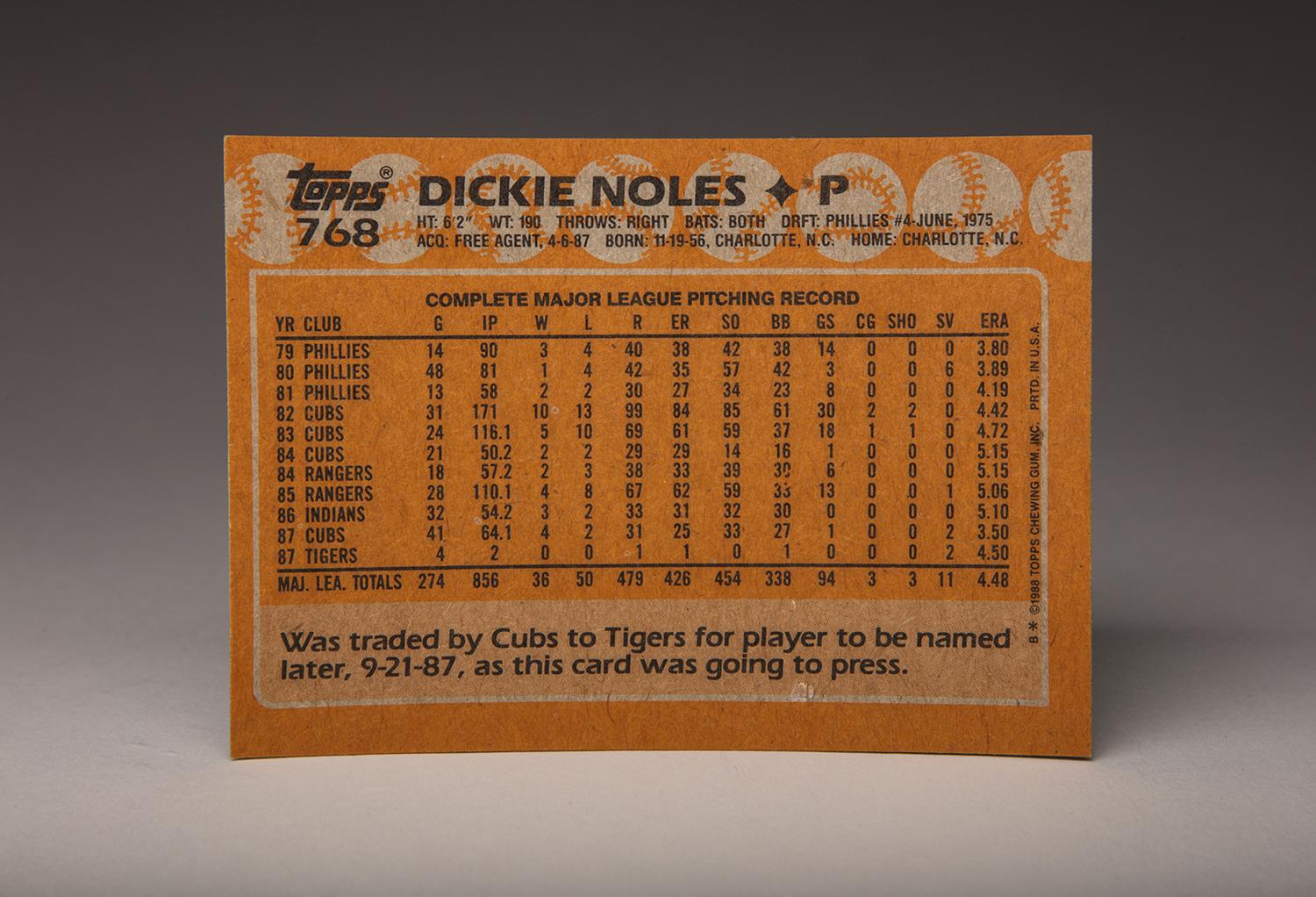

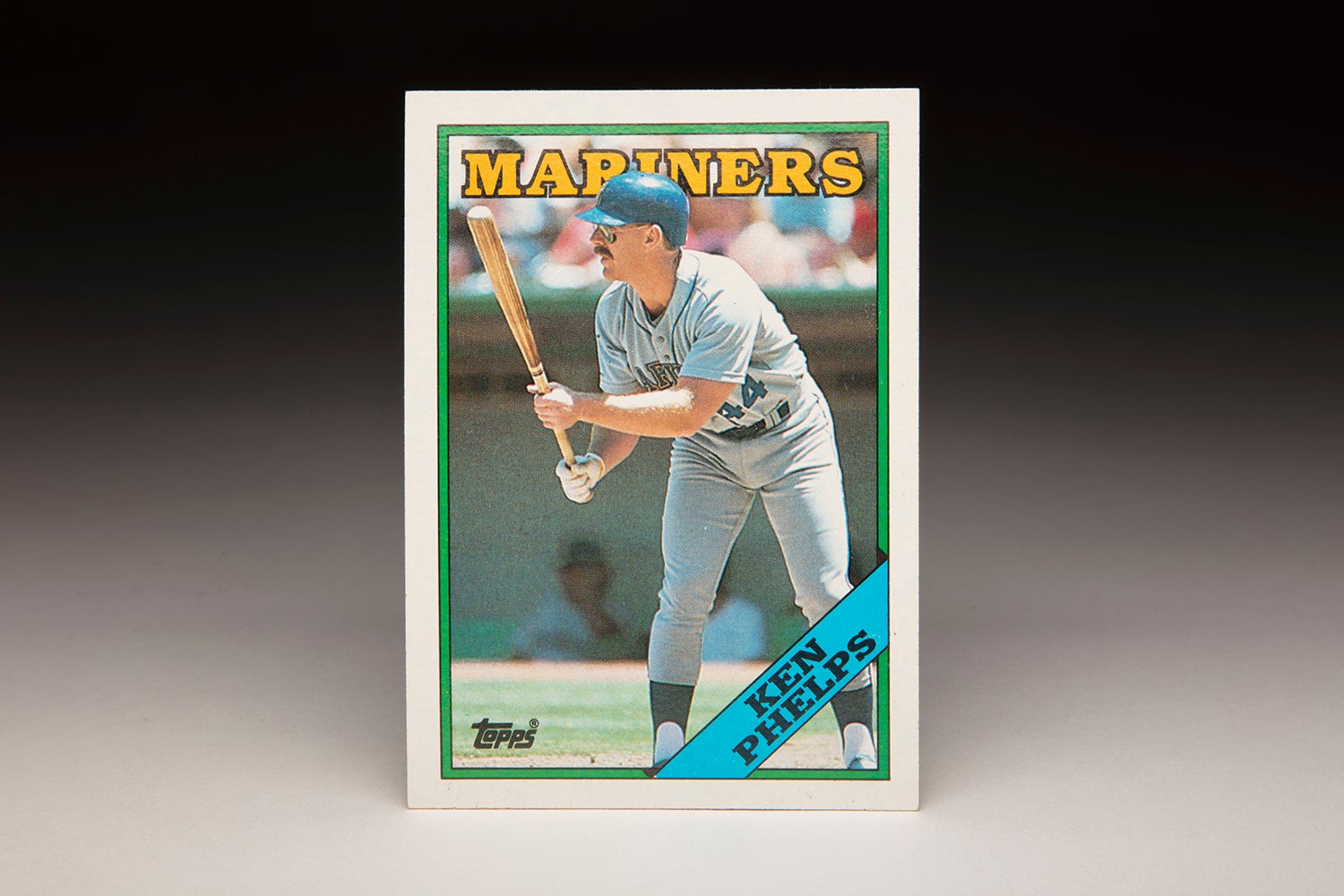

By the 1980s, the Topps Company had reduced the amount of airbrushing that it was doing for players who had been traded or become free agents during the winter. Particularly in the case of those players who switched teams late in the winter, Topps realized that it could more easily update a player’s status by simply putting a small notation on the front of the card.

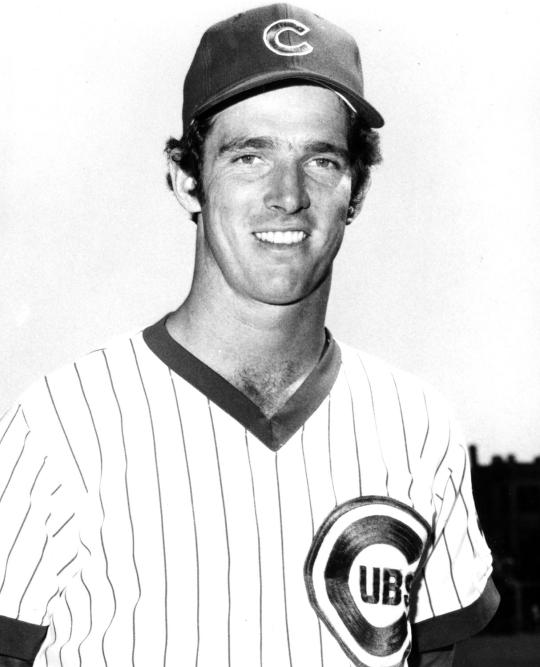

One such example can be found on Dickie Noles’ 1988 card, which clearly shows him wearing a blue mesh road jersey of the Chicago Cubs but contains a notation in simple black font: “Now with Tigers.” Such a method required less effort and less money, while also giving the card the illusion of being up to date.

Noles was a well-traveled player during a journeyman career, so it should not be surprising to see such a notation on his card. Noles’ 1988 card is interesting for another reason, too. As he sits on the sidelines, presumably during Spring Training in Arizona in 1987, Noles has a strange expression on his face. Is it an expression of anger? Or disgust? Or bewilderment? Or perhaps some combination of all of the above?

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

A photo of Noles expressing some intense form of emotion is not exactly a shock. His career was full of emotional flare-ups, some of which could kindly be categorized as “outbursts.” He was a player known to lose his temper and start swinging his fists, symptoms of a more deep-seated problem that plagued him during his playing days.

Noles’ tumultuous professional journey began in 1975, when the Philadelphia Phillies selected him in the fourth round of the MLB draft. The Phillies took a chance in signing Noles; he had a live right arm, but he was a troubled youngster who came from a poor, fractured family. He had also been consuming drugs and alcohol since he was 13. As Noles would tell writer J.F. Pirro years later, “I had no life skills, but I was thrust into professional baseball.”

Signing his first pro contract less than two weeks after being drafted, Noles reported to Auburn (NY) of the NY-Penn League, where he flashed a good fastball but battled wildness – and his temper. The following year, he moved on to Spartanburg of the Western Carolinas League; that’s where he endured a horrific season, reflected by a 4-16 won/loss record and an ERA of 5.91.

The erratic right-hander started to show some real promise in 1977, when he won 10 games in the Carolina League and lowered his ERA to 3.66. He also struck out 114 batters in 199 innings. After a solid season for Double-A Reading in 1978, Noles logged some more minor league time in 1979 before finally receiving his first call-up to Philadelphia in midsummer. The Phillies made him part of their regular rotation and watched him pitch decently in 14 starts as a rookie.

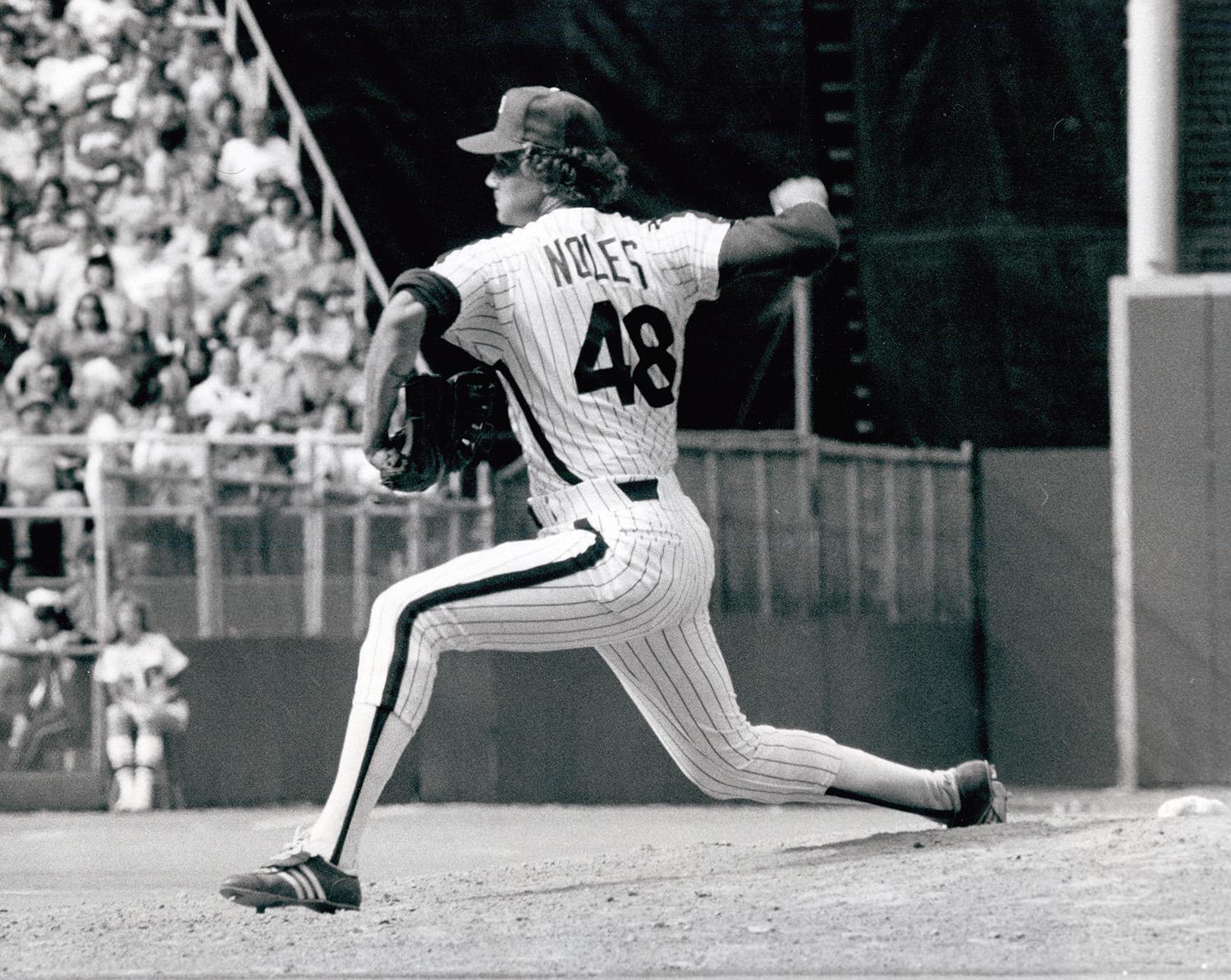

The 1980 season marked a breakthrough for Noles. Converted to the bullpen, he did solid work pitching for new manager Dallas Green, who had replaced longtime skipper Danny Ozark. Noles’ rubber arm and hopping fastball made him a nice addition to a bullpen that already featured veterans Ron Reed and Tug McGraw and another promising pitcher in left-hander Kevin Saucier. But Noles’ season did not come without some controversy. During a game on June 17 at Dodger Stadium, Noles protested a call by throwing his bat and helmet out of the dugout and in the general direction of first base umpire Joe West. For that, Noles received a three-day suspension and a $500 fine.

In spite of such antics, Noles performed an important complementary role for a Phillies team that would jell under the fiery leadership of Green. The Phillies won 91 games to take the National League East, and then upended the Houston Astros in the Championship Series. Noles made two appearances in that series, pitching scoreless relief despite walking three batters in two and two-thirds innings.

It was during the World Series that Noles truly entered the national spotlight, and for a variety of reasons. With a bushy head of hair, blown out in a 1980s perm, Noles certainly looked distinctive on the mound. In Game 4, Noles came on to relieve Larry Christenson in the first inning, with the Phillies already trailing, 4-0. Noles proceeded to shut down the Royals, allowing just one run over four and two-thirds innings.

The Phillies ended up losing the game, but some observers have pointed to something that Noles did in the fourth inning as the turning point of the Series. Always willing to pitch inside and intent on sending a message that the Phillies would not be intimidated, Noles threw an inside fastball under George Brett’s chin, causing the Kansas City Royals star to fall backwards onto the ground. The pitch incensed Kansas City manager Jim Frey, who angrily pointed a finger at Noles. The umpires issued warnings to both teams, and while nothing inflammatory happened the rest of the game, Brett’s bat proved quiet for the remainder of the Series. The Phillies won the fifth and sixth games to take home the first world championship in franchise history.

Noles has always tried to minimize the importance of the Brett knockdown, but some members of the Phillies described it as a watershed moment in the Series. Dallas Green believed that the purpose pitch helped the Phillies. “I don’t think you can say that was the one thing that turned around the Series, but it was a big piece of the puzzle,” Green told Jim Salisbury of the Philadelphia Inquirer. “We were struggling, and it brought us back into focus.”

The pitch also enhanced Noles’ reputation as the No. 1 headhunter in the National League. With that reputation in place, Noles returned to the Phillies’ organization in 1981, but a poor Spring Training resulted in his demotion to Triple-A Oklahoma City. He remained there for most of the summer and found himself in trouble when he struck the owner of a restaurant in the face, prompting an arrest and a lawsuit. That marked a pattern that Noles would replicate for the rest of his career. “I was arrested in every minor league town I played in,” Noles would tell Steve Serby of the New York Post in 1989.

Willing to give Noles another chance, the Phillies brought him back to town in August. Appearing in 13 games down the stretch, Noles struggled with his control and finished the season with an unsightly ERA of 4.17. To make matters worse, Noles became involved in a fight with Phillies general manager Paul Owens. Noles expressed his displeasure with Owens over being demoted to the minor leagues earlier in the season. The verbal exchange led to a physical altercation, which resulted in a call to the local police department.

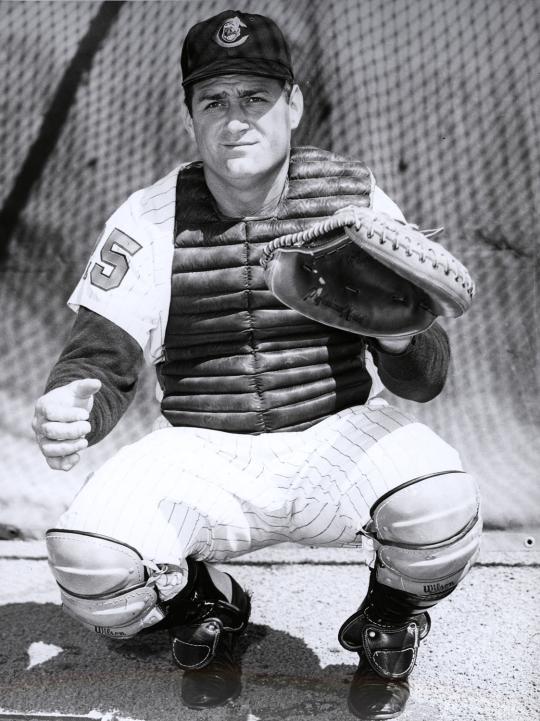

That incident, coupled with Noles’ spotty performance, sealed his fate in Philadelphia. That winter, the Phillies shopped Noles to other teams. At the 1981 Winter Meetings, they found the right deal, packaging Noles with young catcher Keith Moreland and sending them to the Cubs for veteran right-hander Mike Krukow.

Essentially taking Krukow’s slot in the rotation, Noles made 30 starts and won 10 of them. His ERA climbed to 4.42, which was partially attributable to the demands of pitching at Wrigley Field. He returned to the Cubs’ rotation in 1983, but his performance flatlined; he won only five games and lost his spot in the rotation.

Noles’ on-field performance told only a fraction of the story in 1983. During a road trip to Cincinnati in early April, Noles went to a downtown bar, where he drank too much and began brawling. (For Noles, fighting became a frequent companion to his habit of heavy drinking.) The bar’s bouncers, frustrated with Noles’ behavior, refused to allow him to leave the bar, instead calling the police. Soon after the police arrived, Noles puts his hands on the neck of police officer Kevin Cohen and began choking him.

Noles was charged with assault, resisting arrest, and disorderly conduct while intoxicated. In July, Noles returned to Cincinnati to stand trial.

Pleading no contest to the charges, Noles received what amounted to a sentence of 16 days in jail and a fine of $1,000. (Later on, he would have to pay the police officer additional money to complete the terms of a lawsuit.) Standing in front of the court room, Noles took the blame for what transpired that awful night in Cincinnati. “I’m ashamed and sorry at what I’ve done. I’m humiliated as I stand here and hear about it. I didn’t realize I had a [drinking] problem.”

While that fateful night at the bar in Cincinnati had brought him humiliation, it also marked a turning point in Noles’ life. He realized that he could not continue to live life in such a way. “That’s the last drink I had,” Noles told the New York Post several years later in recalling the details of that night.

After the night of the incident, Noles stopped drinking and checked into an alcohol rehabilitation facility. In light of that, the judge in Cincinnati gave him 14 days of credit against an original sentence of 180 days. The judge then suspended an additional 150 days of the sentence, reducing Noles’ incarceration to only 16 days. It was a remarkable show of leniency that allowed Noles to return to the Cubs in 1983.

Unfortunately, the April 9th incident not only landed Noles in jail, but it also had a profound effect on his pitching. In fighting with the arresting officer that night, Noles badly hurt his right knee, causing damage that was never fixed. “I lost eight to 10 mph on my fastball that one night out,” Noles told J.F. Pirro many years later. “I realized that I [my knee] was scarred for life.”

In 1984, Noles remained free of alcohol, but his knee – and his pitching – did not improve. A poor start to the season resulted in another trade, this time to Texas. With the Rangers, Noles pitched both as a starter and reliever, but failed to gain any traction, his ERA rising above 5.00 in both 1984 and ’85.

After the latter season, the Rangers released Noles, who found work with the pitching-hungry Cleveland Indians. Noles appeared in 32 games for the Indians, but found no more success with Cleveland than he had experienced in Texas. After the season, Noles became a free agent, remaining unemployed until the Cubs brought him back in April of 1987. Noles found a groove that season, putting up an ERA of 3.50 in 41 games.

With the Cubs out of contention, they decided to trade Noles in late September, sending him to the Detroit Tigers for a player to be named later. That “player to be named” turned out to be Noles. After appearing in four games for the Tigers, Noles was returned to the Cubs. In so doing, he became one of four players to be traded for himself, joining a list that includes catchers Harry Chiti and Brad Gulden, and utility infielder John McDonald.

About a month after being returned to the Cubs, the team granted Noles free agency. The following spring, he found work with the Baltimore Orioles, first at the minor league level before receiving a two-game midseason audition that turned out to be disastrous. At season’s end, Noles became a free agent yet again, signed with the New York Yankees, and reported to Spring Training, where he was reunited with his former manager, Dallas Green. Green gave him a long look, but Noles failed to make the Opening Day roster, instead spending all of ’89 as the closer for the Triple-A Columbus Clippers.

In the spring of 1990, the Phillies decided to take a flier on their onetime draft choice. Noles appeared in one game, giving up two hits and a run in less than an inning, and then went back to the minor leagues for the rest of the season. Unwilling to give up his quest, Noles headed south for a stint in the Mexican League. After pitching for Jalisco in 1991, Noles finally called it a career, bringing his whirlwind of travels – including six major league teams in a dozen years – to an end.

For Noles, his career was one that involved too much unfulfilled promise, and too many nights spent in bars, at least during his early years. If the story ended there, it would be a sad one. But it did not end with his retirement.

Two years later, Noles rejoined the Phillies to work in their community relations department. Becoming a crucial part of the team’s outreach effort, Noles developed a presentation that he calls “Athletes, Attitudes, and Addictions.” During a typical season, he would travel to roughly 70 minor league games to talk directly to young players about the problems of alcohol and drug abuse. If a player needed one-on-one help, Noles would take the time to sit down with the player and offer him insight based upon his own addiction to alcohol.

It didn’t take long to realize that that Noles was not just a figure head who made the occasional public appearance, but was fully committed to the job of advising young players. Attending training sessions and workshops, Noles became a certified substance abuse counselor. In October of 1994, the New Jersey Governor’s Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse issued a resolution commending Noles for his work with young addicts and alcoholics. The council honored Noles for his unselfishness and his willingness to volunteer his time beyond the normal scope of his job with the Phillies.

A few years later, Noles made a trip to Cooperstown with his family, including his son, and was given a tour by the Hall of Fame Library’s staff. During the tour, Noles asked to see his biographical file, housed in the Hall’s Research Department. He wanted one of his sons to see the newspaper and magazine clippings about him, not just those featuring his accomplishments and highlights, but also the stories about him falling into trouble and being arrested. Noles wanted his son to see the firsthand evidence of his own failures, so that the boy would not repeat the mistakes of the father. For those staff members who were there, it was a poignant moment, one that showcased how a onetime bad boy of baseball had become one of its best citizens.

If Noles were to have a card of him made in 2018, it could say “Still with Phillies.” He has remained with the organization since 1992, spreading the good word while refusing to run from his past. The fighting and the drinking have long since ended, and he doesn’t lose his temper the way that he once did. Instead, Dickie Noles is making life better for the next generation of ballplayers.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame