- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dion James

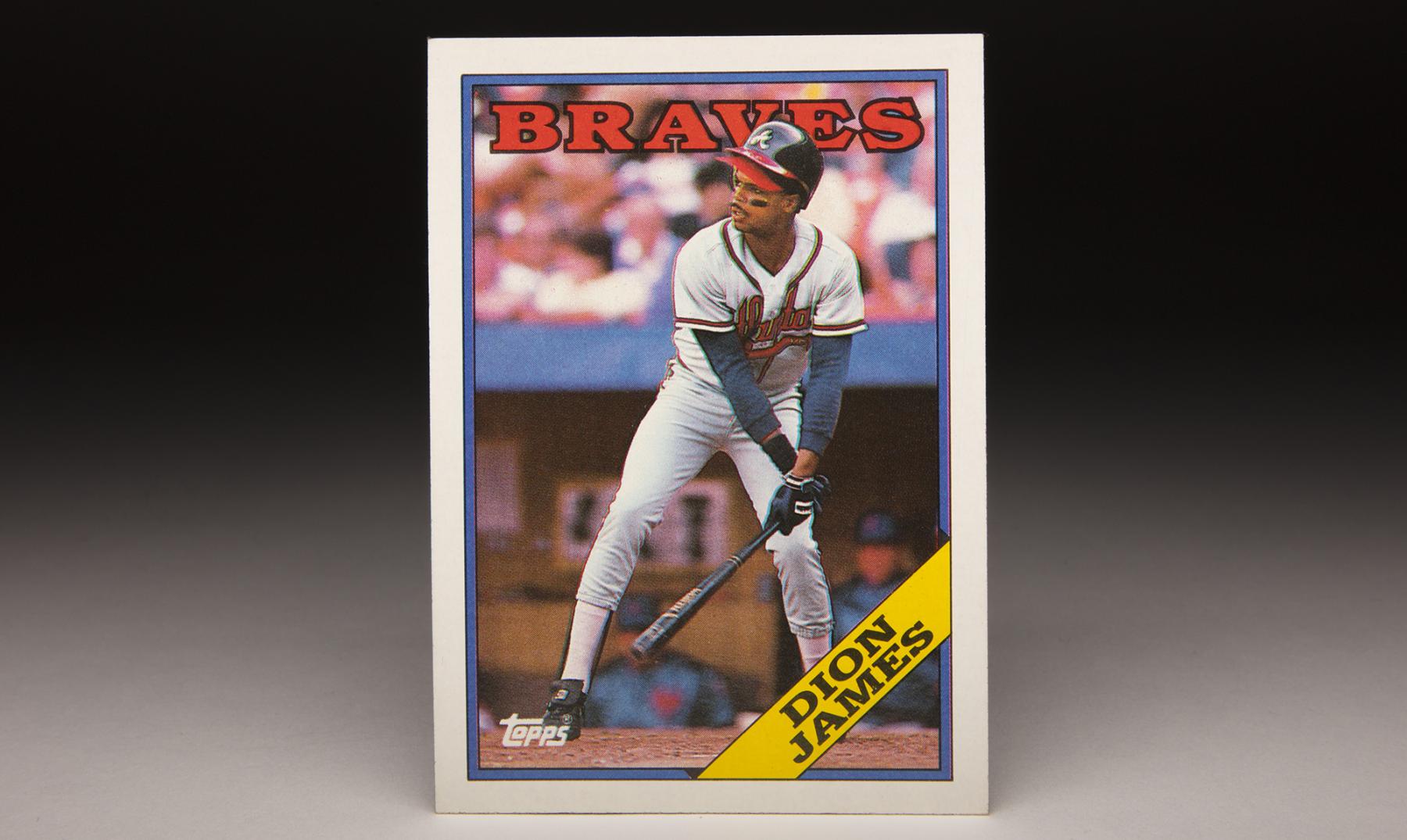

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Dion James

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

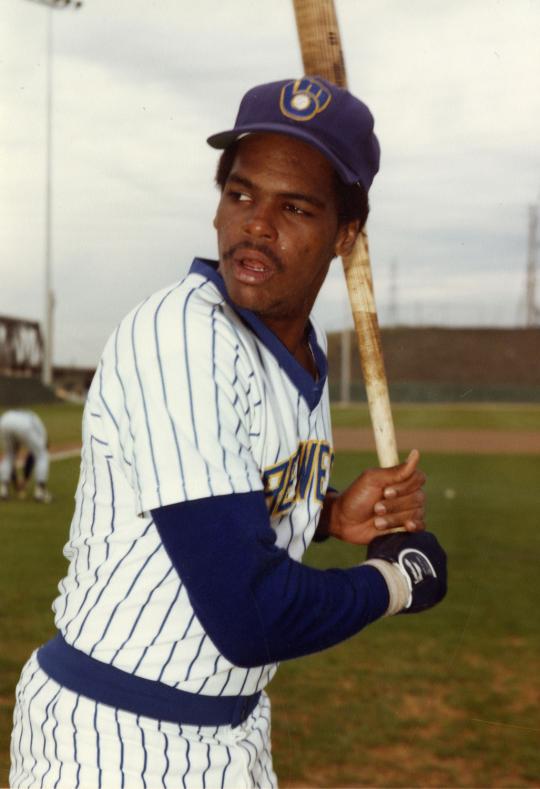

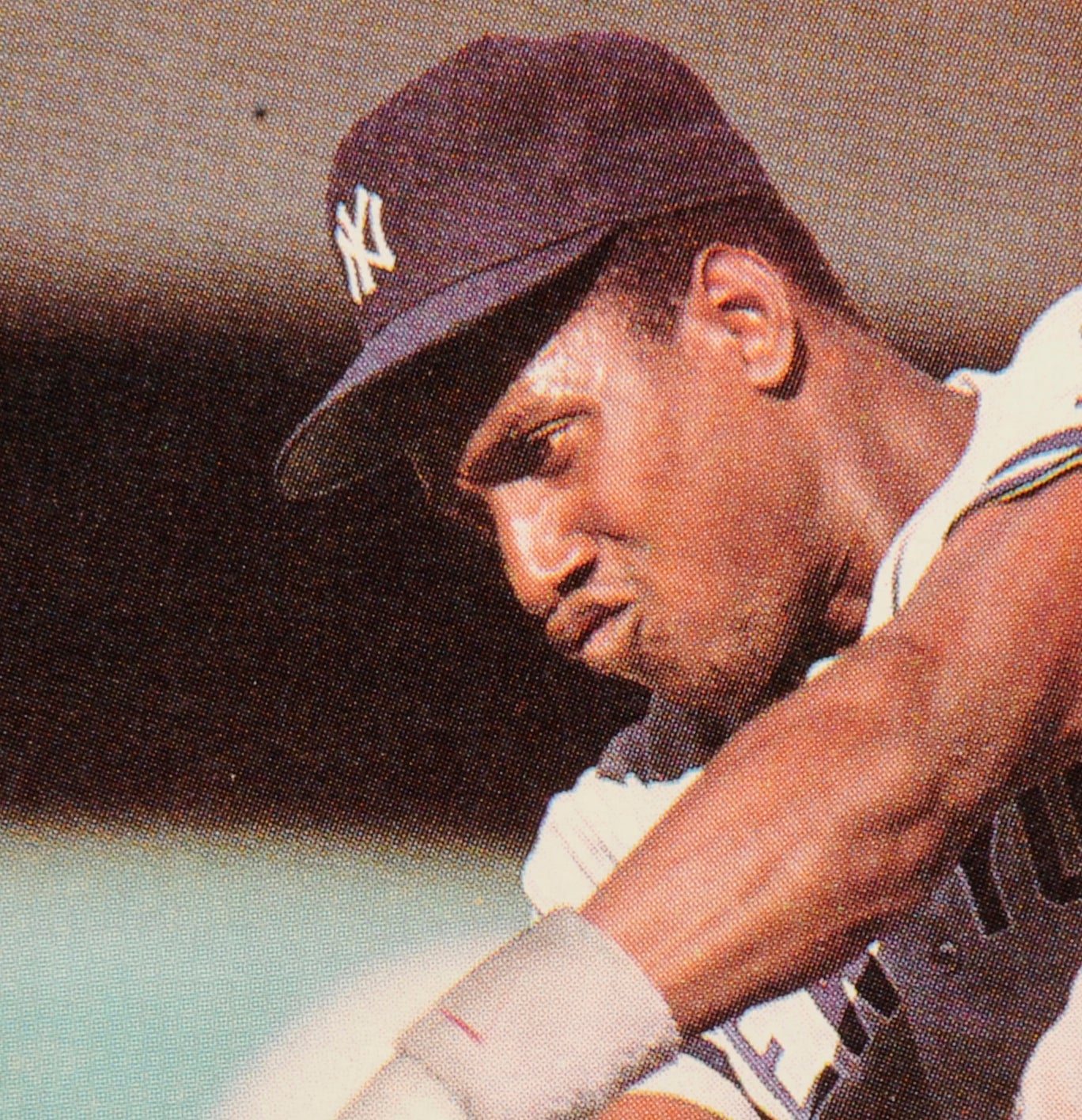

This is exactly how I remember Dion James.

Every once in a while, a baseball card portrays a ballplayer in a way that is so accurate that it almost brings chills. Such is the case with the James card in 1988. It’s as if I’ve been transported back to the mid-1980s, those early days of cable television, when Superstation WTBS made its way into just about every broadcast market.

I can remember watching the Braves play and James taking his at-bats. As he waited for the next pitch, James would lift his front foot slightly, just as he is doing on this Topps card. Almost simultaneously, he would lower his bat and point it toward the ground. Boom, he’s doing exactly that on this card.

Beyond that, let’s take a look at James’ fashion choice. He is doing something rarely seen in today’s game: Wearing his cap underneath his batting helmet. This is a habit that we used to see more often back in the 1970s, from notable players like Eddie Murray and Bobby Murcer and Al Oliver. In more recent years, I can recall Juan Pierre doing this, but not many others. Perhaps today’s helmets better fit the heads of the players, removing the need to wear a cap underneath. Whatever the reason, I like the James style; there is something cool about the cap under the helmet.

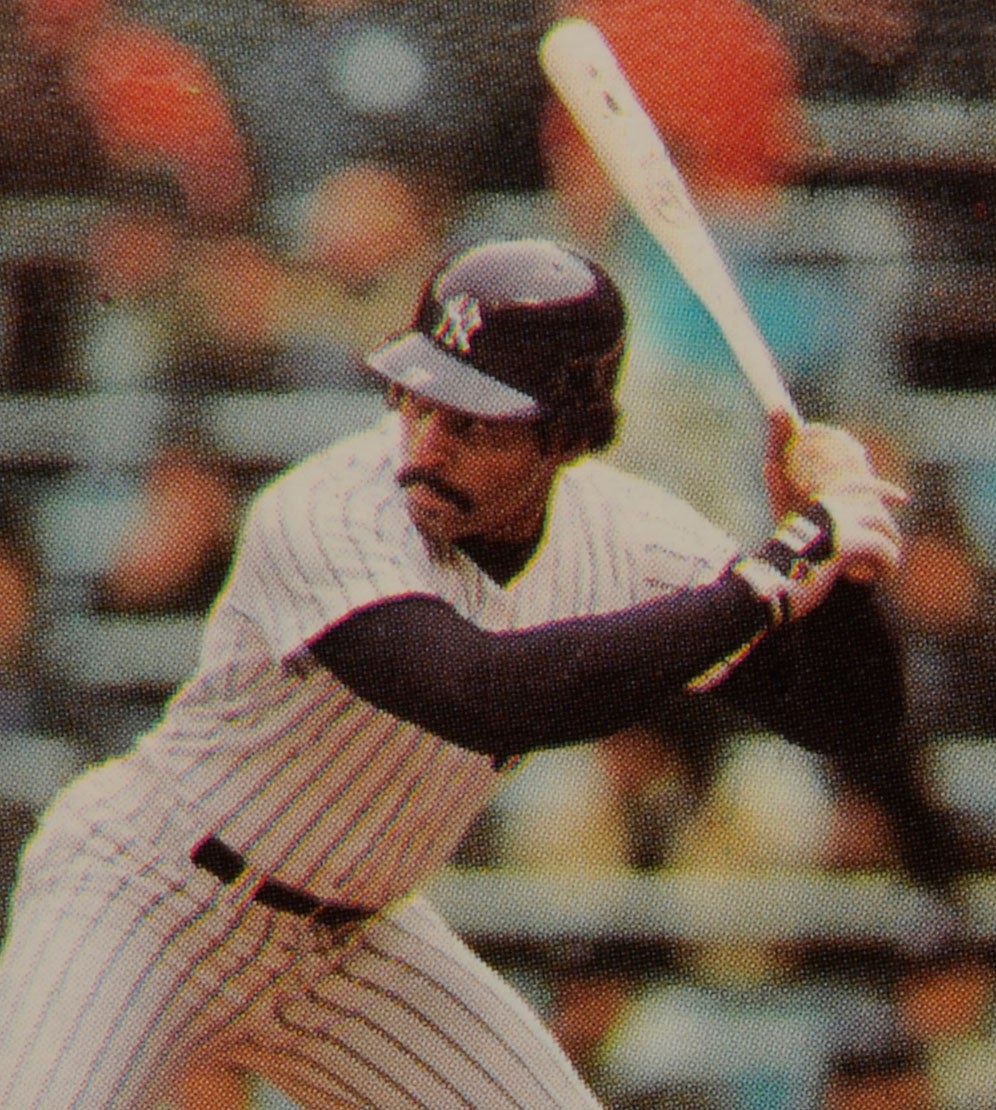

From fashion to batting stance habits, no card could capture James any better than his 1988 Topps selection. It’s also a nice clear shot from an afternoon game at Shea Stadium. It’s a card that I’ve always liked, but one that I gain more appreciation for the more that I learn about James’ fragmented journey in the 1980s and 1990s.

It’s easy to forget that James was once one of the most touted amateur players in the country. In 1980, the Milwaukee Brewers made him their first-round draft choice, taking him 25th overall, well ahead of future stars like Danny Tartabull, Doug Drabek and Eric Davis.

The Brewers promptly assigned the 17-year-old outfielder to Butte of the Pioneer League, where he hit .317 and earned a fast promotion to Burlington at the tail end of the season. James would again hit over .300 for Single-A Stockton in 1981, but his season was marred by a violent incident. On the day of a rainout, James made the short trip to see his parents in nearby Sacramento. During the trip, James was assaulted by several youths, who took turns hitting him with wooden boards. The frightening incident left James briefly unconscious and laid out in a hospital bed for a full week.

James continued to hit .300 or better each of the next two seasons, first at Double-A El Paso and then at Triple-A Vancouver. He also showed a good eye, consistently totaling more walks than strikeouts. There was no doubt about James’ ability to hit for average, reach base, or steal bases, topped off by a total of 41 steals for Stockton in 1981. All that James lacked was power, but the Brewers hoped that would come in due time.

After pasting Pacific Coast League pitching at a .336 clip in 1983, James earned a September call-up to Milwaukee. He struggled in 20 at-bats, but the Brewers kept him on their Opening Day roster in 1984. Although James played almost all of his minor league career as a center fielder, the Brewers used him as part of a platoon in right field. He did well, hitting .295 and compiling a .351 on-base percentage. But he struggled in other areas. He hit only one home run, an almost unacceptable total for a corner outfielder. And his baserunning lacked polish. He was caught stealing on 10 of 20 attempts, well below the threshold of 75 percent that most analysts consider a minimum level of efficiency.

The Brewers hoped that James would continue his development in 1985, but a major injury laid waste to the season. During Spring Training, James separated his non-throwing shoulder while trying to make a diving catch. He then re-aggravated the injury in May, knocking him out for a good portion of the season.

He spent part of his time in Vancouver on a rehab assignment, but angered the organization with his attitude. James wanted no part of Triple-A, upsetting his coaches and managers in the process. In spite of the difficulty, the Brewers brought him back in September, but it was too late to salvage a lost season.

In 1986, James suffered another setback. After a disappointing spring in 1986, the Brewers sent him back to Triple-A Vancouver. He spent the entire summer in Canada, where his average settled at .282, well below his previous minor league standard. While his play suffered, his attitude improved exponentially. “It was like night and day, the difference in Dion,” Vancouver pitching coach Mike Paul told Gerry Fraley, reporting for the Sporting News. “He was a pleasure to be around. He was the first one on the field, and the last one off.”

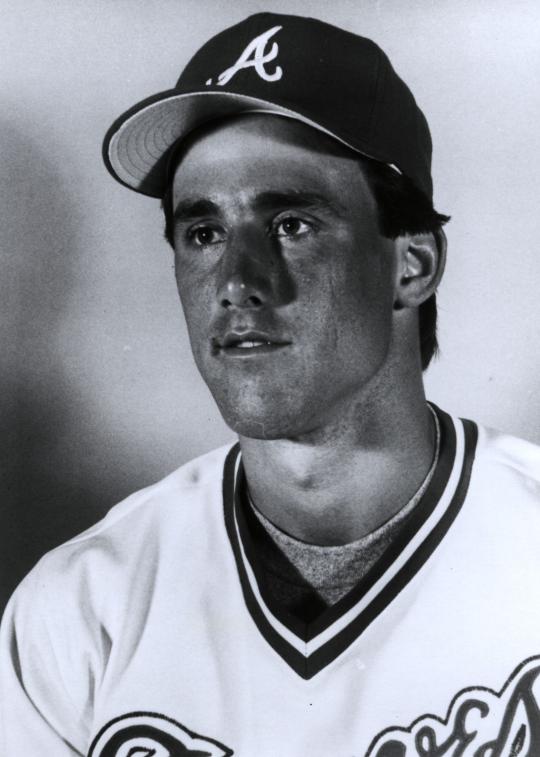

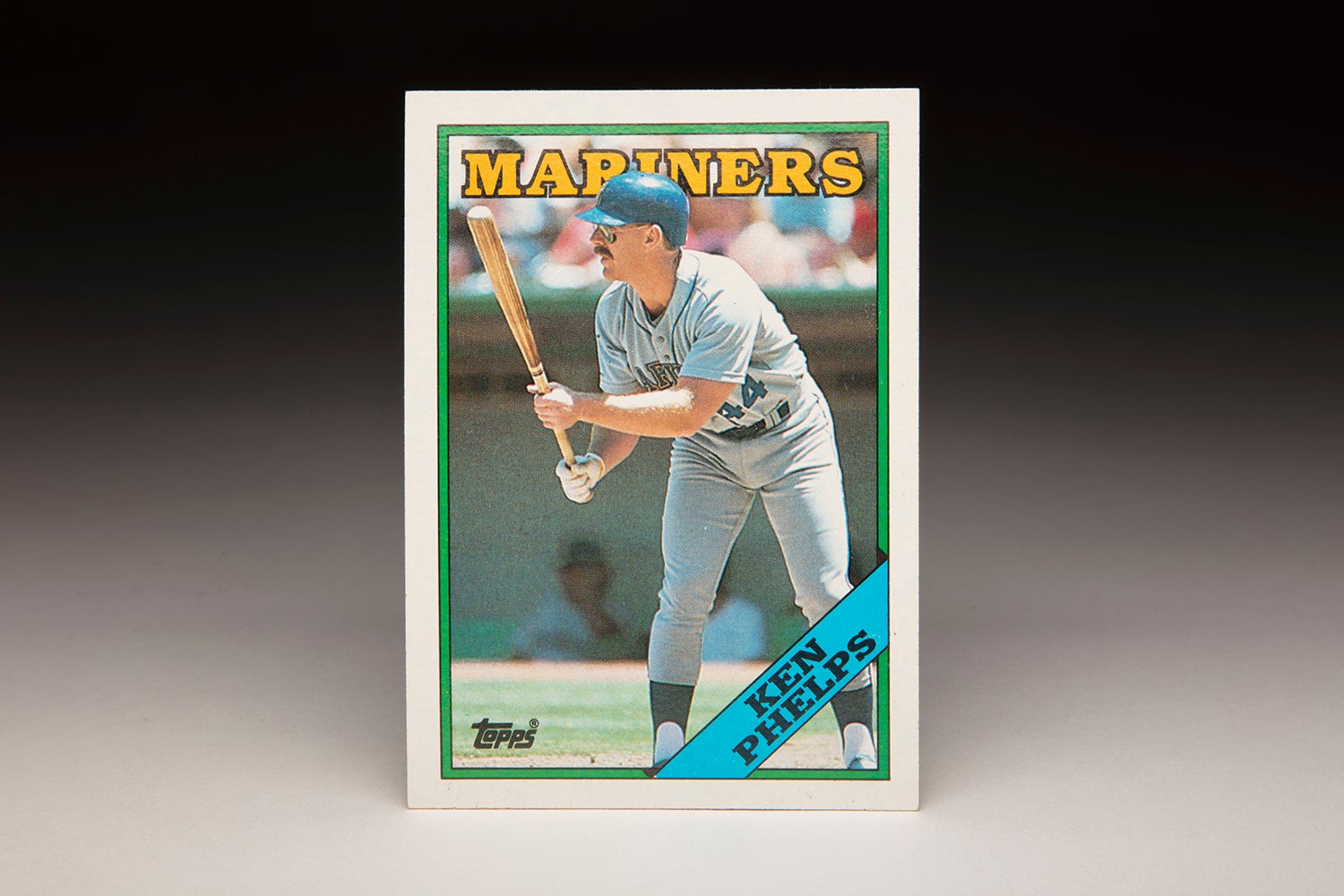

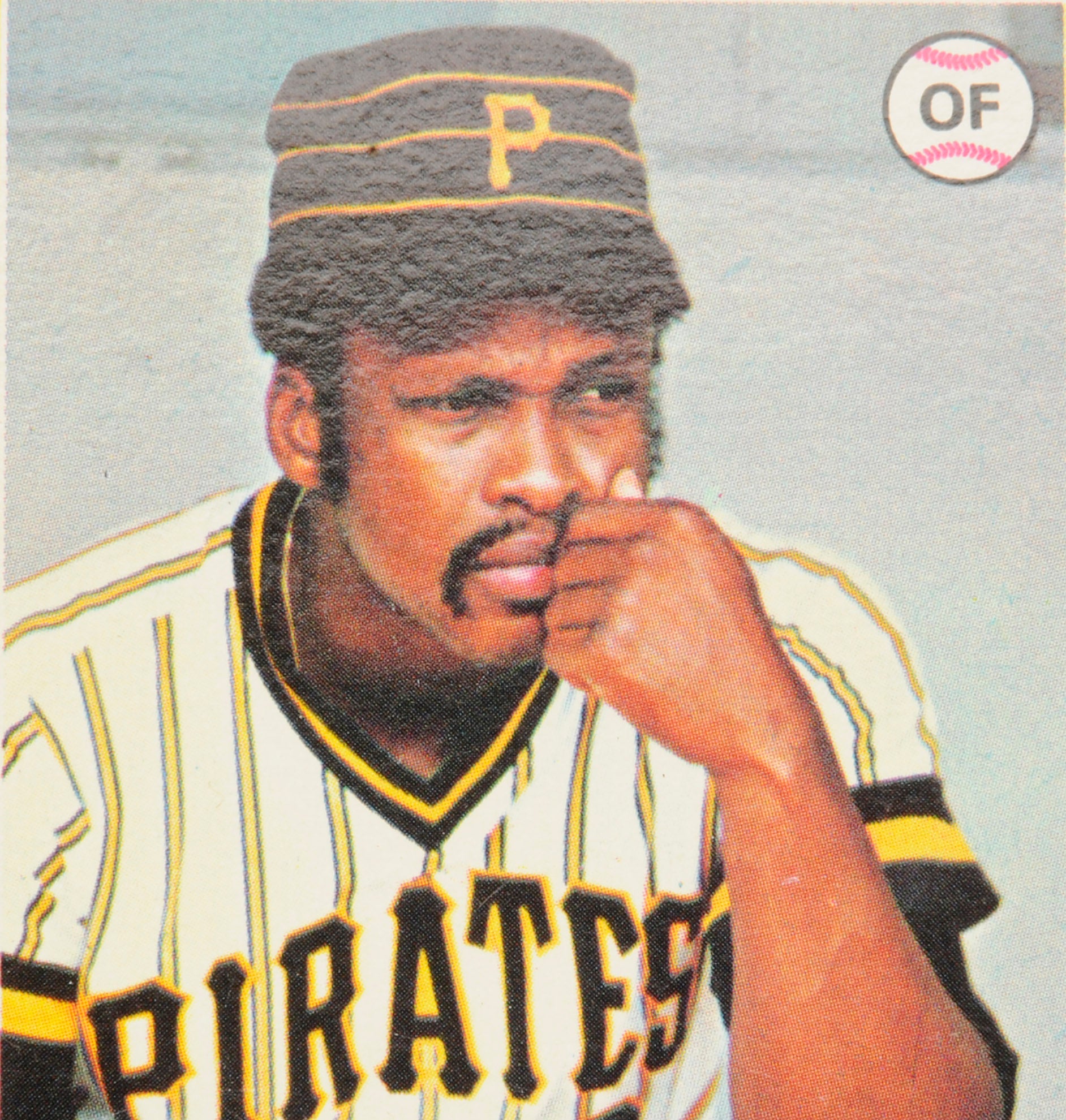

His attitude repaired, James still posed a question mark because of his declining play, leaving the Brewers in a quandary. They doubted whether James would ever live up to the billing that came with a being a first-round draft choice. So that winter, the Brewers decided to cut the cord, sending James to the Atlanta Braves for another top outfield prospect who had failed to develop, a young slugger named Brad Komminsk.

The Braves, spearheaded by general manager Bobby Cox, decided to make an immediate change with James, who had played primarily right field with the Brewers. Hoping to take advantage of their newcomer’s footspeed, the Braves made James their center fielder. The move did not come without some controversy, since it necessitated the fulltime move of the team’s star player, Dale Murphy, from center to right field.

James began the season well, picking up eight hits in his first 18 at-bats, while also drawing seven walks. The start to the season also brought a memorable incident. On a Sunday afternoon at Shea Stadium, James hit a routine fly ball to left field. As Mets left fielder Kevin McReynolds camped under what seemed like a sure out, the ball hit a bird flying at Shea. The collision killed the bird, which fell to the outfield grass, where it was picked up by Mets shortstop Rafael Santana. In the meantime, the fly ball dropped to the outfield, in front of McReynolds, allowing James to reach second base on perhaps the strangest double in big league history.

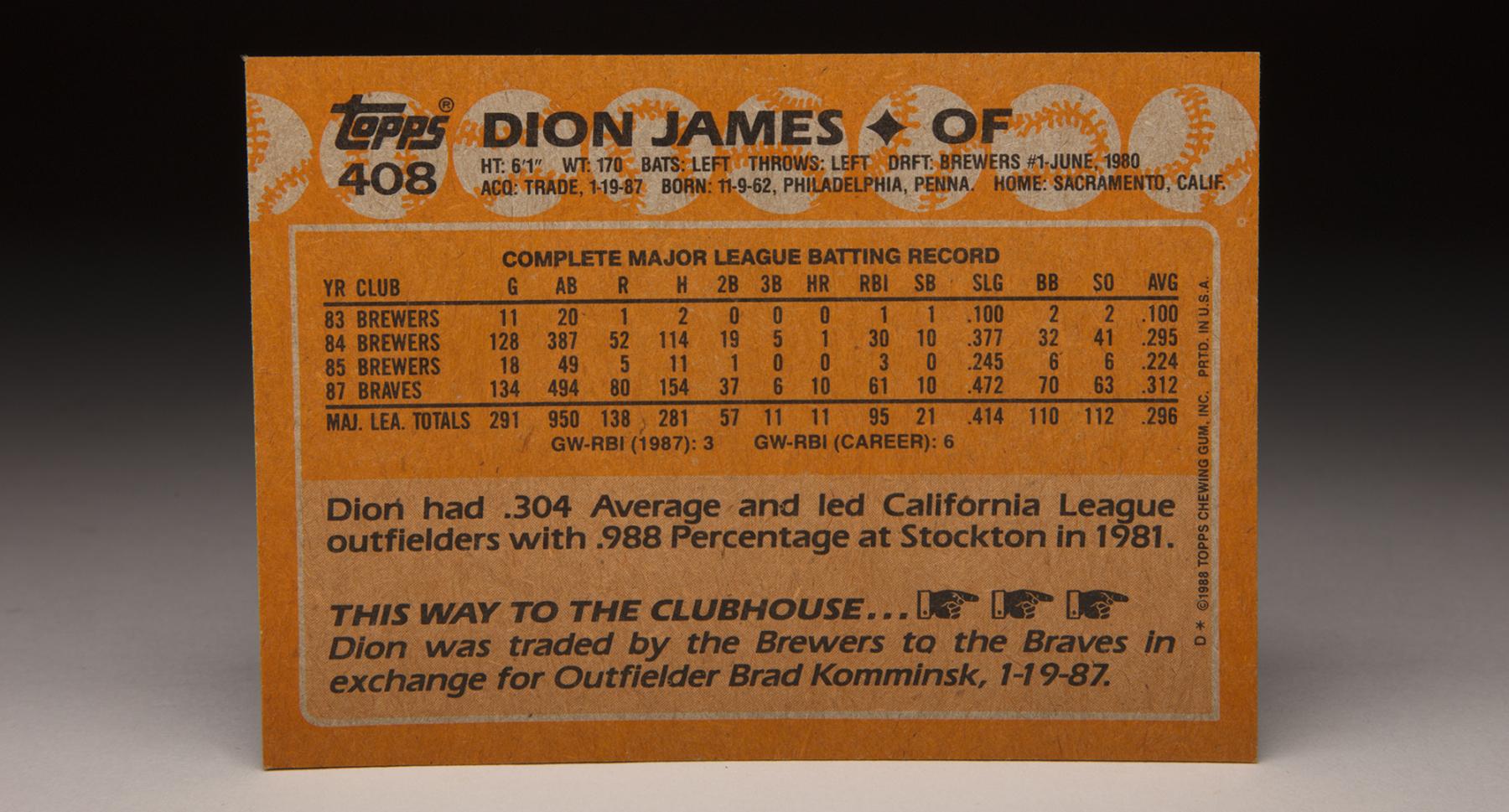

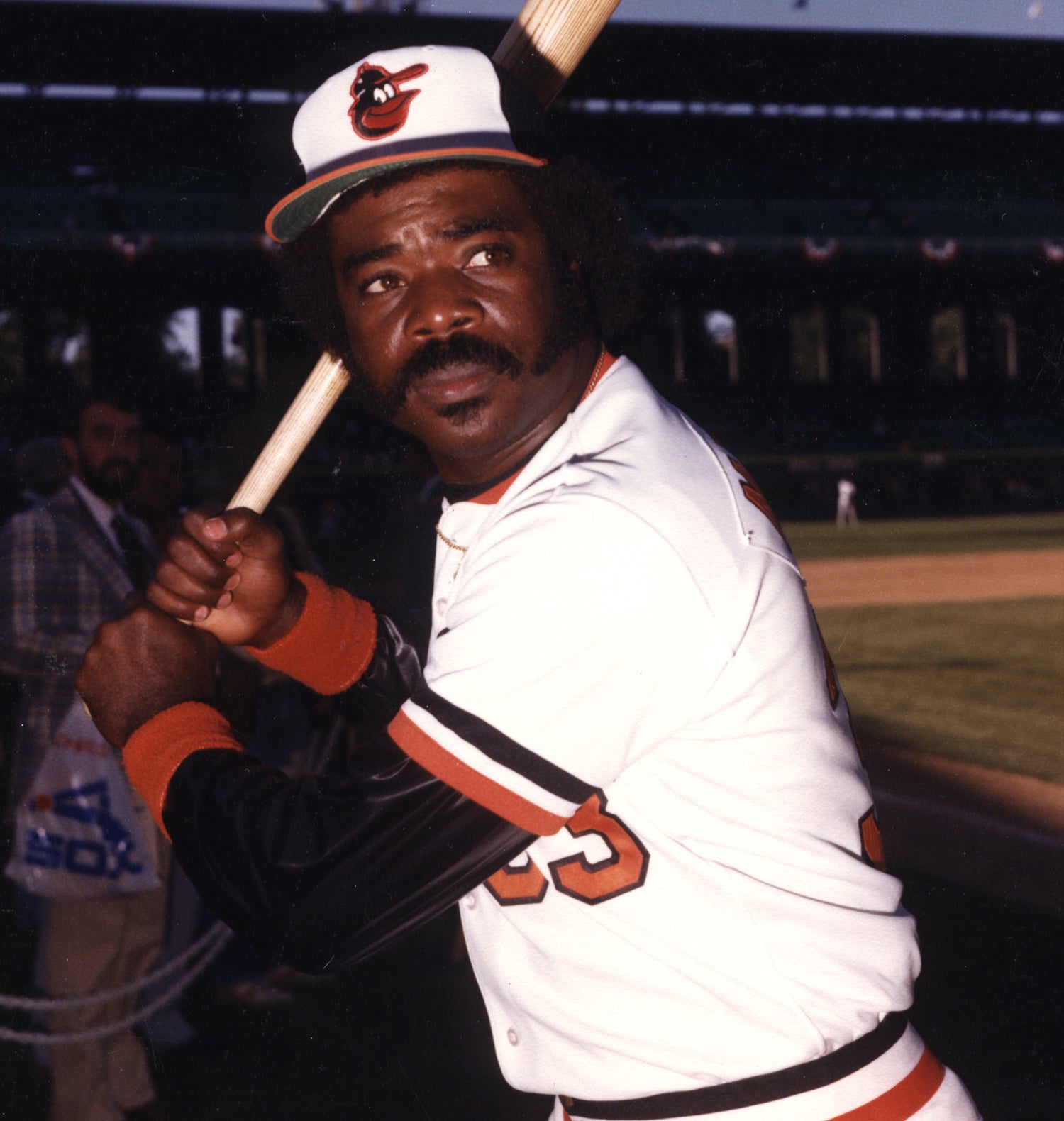

On July 2, 1989, the Atlanta Braves traded Dion James to the Indians for Oddibe McDowell, who began his big league career with the Rangers. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

While the incident garnered headlines, James continued to do his job quietly – and well. Simply put, James blossomed in a Braves uniform. He batted .312, drew 70 walks, and put together an on-base percentage of .397. Most surprisingly, James showed a trace of power for the first time in his career. He hit 10 home runs and slugged .472, by far the best marks of his career.

James’ breakout season of 1987 coincided with the Braves’ switch to new uniforms (which brought back the old tomahawk logo) and also made his 1988 Topps card a little more desirable. Unfortunately, James could not sustain the improvement. Moving to left field to make room for prospect Terry Blocker, James saw his batting average sink to .256 and his home run total fall to three in 1988. James still reached base 35 percent of the time, but his level of player was nowhere near the borderline stardom the Braves had seen the previous summer.

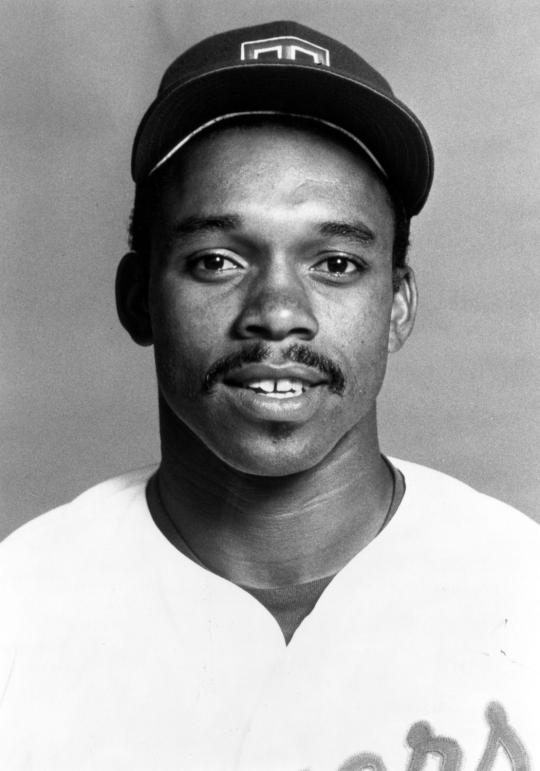

In 1989, the Braves made some changes to their outfield. They acquired veteran Lonnie Smith in a trade, moved Murphy back to center field and handed right field to another young left-handed hitter, Tommy Gregg. The changes left James in the role of fourth outfielder. After a mediocre start to the new season, James became trade bait. In July, they dealt him to the Cleveland Indians for another once-heralded prospect, Oddibe McDowell.

The Indians made James a part-time left fielder, where coincidentally enough, he shared playing time with Komminsk, the player for whom he had once been traded. James responded well to the change in scenery, hitting .306 over the balance of the season. The lack of power, however, concerned the Indians.

In 1990, they opted for an outfield featuring three players capable of hitting the long ball: Candy Maldonado, Mitch Webster and Cory Snyder. James once again returned to the fourth outfielder role and did capably, compiling a .347 on-base percentage. But James did not like his role as a backup outfielder. At season’s end, he asked the Indians to release him. The team complied with the request.

At 27 years old and coming off a decent season, James thought he would find a good market for his services, but the best he could come up with was a non-roster invitation to Spring Training with the New York Yankees. James reported to Fort Lauderdale, but from the beginning of camp, he struggled with pain in his throwing elbow. James failed the team’s physical, voiding his contract with the Yankees.

Legally, the Yankees owed James nothing in terms of financial competition, but the team offered to pay for his season-ending surgery: a procedure called an ulnar nerve transplant. “That made me feel wanted,” James told Joel Sherman of the New York Post. “It made me work hard. The Yankees showed a lot of interest in me.”

Five times a week, James took part in elbow-strengthening exercises with the trainer of the NBA’s Sacramento Kings, who lived near James. For most of the season, James went without a paycheck. He called the experience “humbling,” but one that helped him “develop character.” That winter, James played 26 games in the Dominican Winter League, proving to himself (and others) that he was now healthy. The Yankees decided to bring James back for Spring Training in 1992.

James made a terrific first impression. He reported to camp having lost 20 pounds, making him quicker in the outfield. Yankees manager Buck Showalter told reporters that James would have to show himself capable of running well, both in the outfield and on the bases, in order to make the team. James met all of the standards on the Showalter wish list. He made the team and filled an important role as a utility outfielder, backing up starters Mel Hall, Roberto Kelly and Danny Tartabull.

James played well for the Yankees, showing an ability to get on base nearly 36 percent of the time. Yet, he did nothing spectacular. Certainly, he gave the Yankees no indication of what he would do the following season. With the departure of Hall over the winter, the Yankees developed a need in left field. They move James into a platoon, giving him a chance to play against most right-handed pitchers they faced.

Appearing in 115 games, James lifted his batting average to stratospheric levels, hitting .332 and compiling a .390 on-base percentage. Although James didn’t come to bat enough to qualify for the league batting title, he did lead all Yankee regulars in batting average. Overshadowed by more well-known teammates like Don Mattingly, Bernie Williams and Paul O’Neill, James became a supplementary offensive force. His patient approach and solid defensive play in left field helped the Yankees to an 88-win season, a major improvement over their performances of the last two seasons.

He also became a favorite of this fan and writer, and seemed to develop a niche following among Yankees fans who appreciated his effectiveness and hustle. Given his batting average breakout, it seemed a given that James would return to the Yankees in 1994. Not so fast.

James was now a free agent. The Yankees wanted to re-sign, but the 30-year-old outfielder was now receiving interest from the Japanese Leagues. The Chunichi Dragons were not only offering him a two-year contract worth $4 million, but they were offering a promise of an everyday job, and not a platoon role, in the outfield. For James, the two-fold offer was too good to turn down.

On paper, the Chunichi opportunity seemed like a dream job for a journeyman player. But the offer came with risks. Since the 1960s, a number of American-born players struggled in making the transition to Japan, where cultural expectations were far different. The Japanese approached workouts religiously, priding themselves in long, sweat-filled practices, which created problems for American players. On one occasion, James remembered having to perform calisthenics in the middle of a windstorm.

Then there was the language barrier. According to James, most of his teammates and Chunichi management ignored him, creating an atmosphere of “coldness.” As a result, James spent most of his time with American teammates Alonzo Powell and Dwayne Henry. James also felt that Japanese League umpires showed a bias against American players. “My game is about knowing the strike zone,” James told the New York Post. “I might not be able to hit, but I know the strike zone. They have some decent pitchers and when you give them a strike zone as big as a barn, they are going to have success.”

In contrast, James did not. He batted only .260 with little power. The Dragons became so disappointed in his play that they bought out the second year of his contract, allowing him to return to the States. Given his own unhappiness, James was more than pleased to take the buyout. James hoped to find work with a major league team, but initially found little interest.

That all changed in April of 1995, when the Yankees came up short in the outfield, thanks to injuries to Tim Raines and Ruben Sierra. The Yankees signed James to fill the void as a part-time outfielder and DH. Once again, James did good work for the Yankees. Playing as a fourth outfielder and DH, James batted .287 with a .354 on-base percentage. And for the first time in his career, James advanced to the postseason, as the Yankees won the wild card and earned their first postseason berth since the early 1980s.

James returned to the Yankees in 1996, but appeared in only a handful of games before receiving his release – the result of a glut of outfielders in the Bronx. (James’ departure would prevent him from being part of the Yankees’ world championship run in 1996.) Six weeks later, James signed a minor league deal with his original team, the Brewers, who assigned him to their Class A affiliate at Stockton before moving him up to Triple-A New Orleans. But James never made it back to the major leagues. The Brewers released him in July, ending his professional career.

For James, his career represented a journey that had come full circle. At first a top prospect, he faced criticism of being a disappointment, an underachiever. He struggled with his attitude and endured a series of injuries. But he also mounted a comeback, becoming an important and valuable player with the Braves and Yankees. By the end of his career, he had earned the label of overachiever. Given the chance, after so many dead ends, Dion James made a positive name for himself within our game.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame