#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Oil Can Boyd

The owner of perhaps the most unique nickname in baseball history, Dennis Ray Boyd saw the top of the big league mountain and battled the worst of humanity’s demons.

What is sometimes lost, however, is how good a pitcher the man called “Oil Can” was during his 10-year MLB career.

Boyd was born Oct. 6, 1959, in Meridian, Miss., as the ninth child of Willie and Sweetie Boyd and grew up in a family filled with baseball players. He also came of age in the middle of a racial divide that saw three civil rights workers murdered about 30 miles from his home in 1964.

“I was in sixth grade when the school was integrated,” Boyd told the Meridian Star in 1985. “It was bad. You felt like you were animals.”

With five older brothers, Boyd learned baseball by playing with those who were bigger and faster. Growing into his 6-foot-1, 155-pound frame, Boyd translated his whip-like figure into a formidable fastball.

“God touched Dennis,” Boyd’s oldest brother, Skeeter, told the Providence Journal. “The rest of us were all in the wrong place at the wrong time. We were all pitchers, but he came along later with the same pitches.”

Undrafted out of high school, Boyd enrolled at Jackson State University. As a sophomore, Boyd went 7-2 with a 1.87 ERA for the Tigers, leading the Southwestern Athletic Conference with 64 strikeouts. He was even better as a junior, permitting not a single earned run over his first five decisions.

Boyd credited former big league pitcher Scipio Spinks, who was helping out with the Jackson State baseball program, for his rapid ascension as a pro prospect.

“Because of (Spinks), I’m now looking at the game from a mental point of view,” Boyd told the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Miss. “He has me thinking about every pitch. Every pitch means something. He’s teaching me to pitch with my heart. You gotta have guts.”

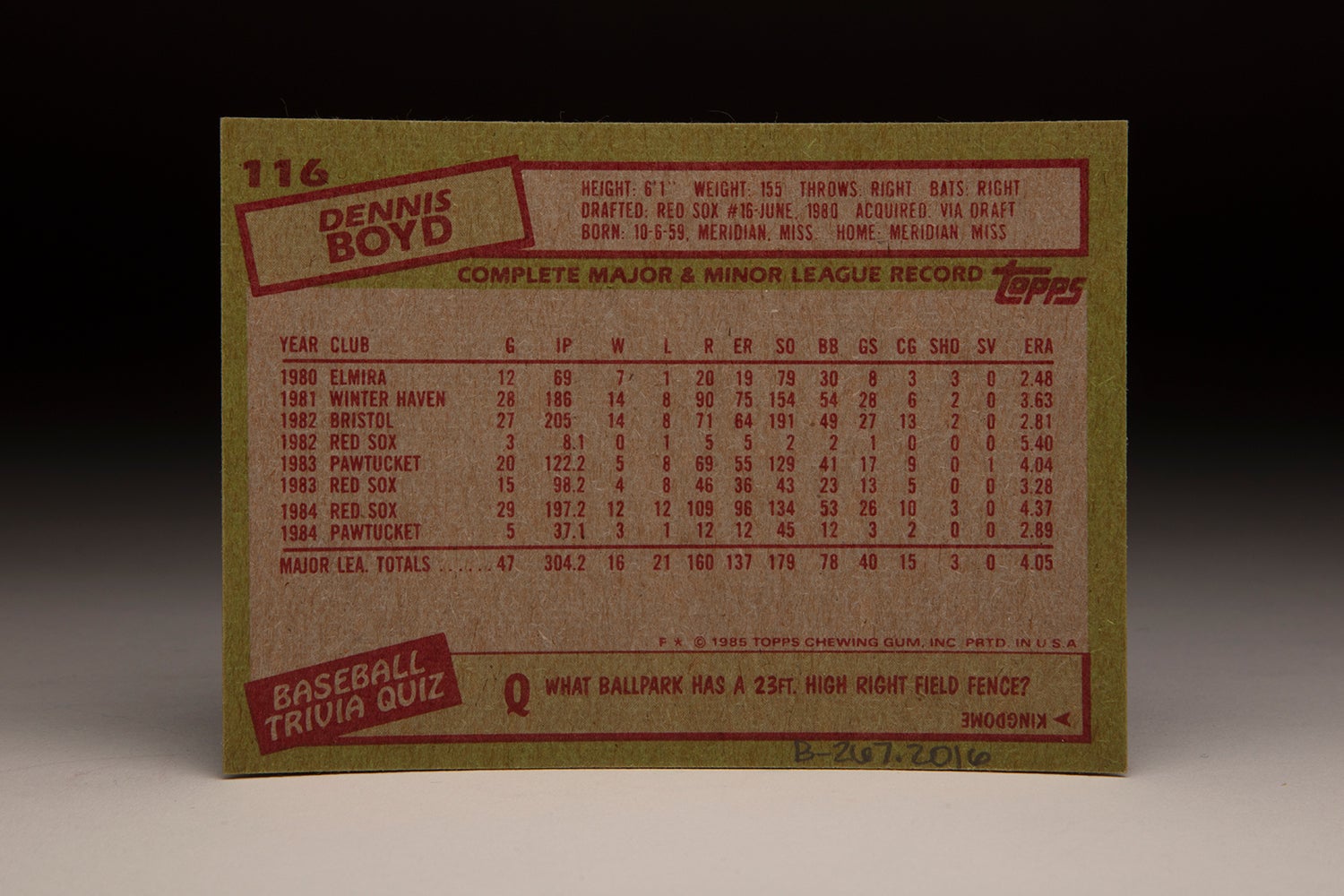

The Red Sox liked what they saw of Boyd and tabbed him in the 16th round of the 1980 MLB Draft. Boyd signed and Boston sent him to Elmira of the New York-Penn League, where he went 7-1 with a 2.48 ERA in 69 innings, fanning 79 batters.

Boyd moved to Class A Winter Haven of the Florida State League in 1981, going 14-8 with a 3.63 ERA. Then with Double-A Bristol of the Eastern League in 1982, Boyd was again 14-8 but with a 2.81 ERA and 191 strikeouts in 205 innings.

That same year, Boyd revealed the genesis of his nickname – one that he repeatedly asked to be called.

“We used to go drinking beer a lot,” Boyd told the Hartford Courant of his high school friend Joe Cecil Blanks while both were growing up in Meridian. “Oh, I could drink up a lot of beer. We called it ‘oil.’

“One night, (Blanks) said: ‘Why, you’re a regular oil can.’ It caught on.”

Bristol pitching coach Bill Denehy, a former big leaguer with the Mets, Senators and Tigers, believed that Boyd’s talent was even bigger than his personality.

“Without a doubt, his stuff is as good as any pitcher in the organization,” Denehy told the Courant in 1982 “He’s a little inconsistent with the slider, but there’s certainly no question that he can throw strikes.”

The Red Sox brought Boyd to the big leagues in September of 1982 and pitched him in three games, with Boyd allowing five earned runs in in 8.1 innings. He impressed observers at Spring Training in 1983 with his pitching and his confidence but was sent to Triple-A Pawtucket for more seasoning.

“I know I don’t have a big frame like most of these guys,” Boyd told Guy Gannett Service in the spring of 1983. “I’m small. But I’ve also got a lot of athletic ability. I’m cocky, too. I don’t mind telling people I can pitch.”

Boyd struggled in 1983 at Triple-A but the Red Sox still believed he was part of their future and brought him back to Boston in June. After going 1-1 with a 5.25 ERA in three games (two starts), Boyd was sent back to Pawtucket.

“Boyd still has major league stuff,” Red Sox manager Ralph Houk told the Courant. “He can’t keep throwing three fastballs. He has to work on the low one. Down there (in Triple-A) he got guys out on that curve in the dirt. That doesn’t work up here.”

Boyd returned to Boston in August and Houk put in in the starting rotation, where Boyd went 3-7 with a 3.01 ERA in 12 appearances (11 starts) down the stretch. He made the Opening Day roster in 1984 and started Boston’s fourth game of the season but was demoted to Triple-A in May after starting the year 0-3 with a 7.36 ERA.

But after going 3-1 with a 2.89 ERA at Pawtucket, the Red Sox once again brought Boyd to Boston. This time, Boyd was ready for the challenge – throwing complete games in three of his first six starts and finishing the season with a 12-12 record, 10 complete games and three shutouts over 197.2 innings.

After a brief holdout in the early days of Spring Training of 1985, Boyd agreed to a one-year deal worth a reported $140,000.

“I’m all right,” Boyd told United Press International after agreeing to the contract. “I’ll come out here and shake it off like nothing ever happened.”

Boyd was a workhorse in 1985, going 15-13 with a 3.70 ERA in 272.1 innings, leading Red Sox pitchers in wins, innings, complete games (13) and shutouts (3). He agreed to a one-year deal worth a reported $370,000 for 1986 – but almost immediately, Boyd ran into trouble.

Boyd told reporters that spring that his weight loss, evident to observers, was caused by non-infectious hepatitis. But in a 2012 book – “They Call Me Oil Can” – written with Mike Shalin, Boyd acknowledged that the hepatitis story was a cover for his cocaine use.

Boyd continued to pitch well in 1986, helping the Red Sox win the American League East. But the season contained more controversy for Boyd when he was suspended twice and missed almost a month of action. He was suspended for three days on July 10 after cursing at teammates, ripping his uniform off and leaving the clubhouse before a game against the Angels in a tirade sparked by his being left off the AL All-Star Game roster despite an 11-6 record. Six days later, he was suspended again after an altercation with police near his home. He later sought treatment for drug addiction.

“I hope to pitch my butt off,” Boyd told the Associated Press when he returned to action in August.

Boyd made 12 starts in August and September, going 5-4 with five complete games. He finished the season with a 16-10 record and 3.78 ERA as Boston rode the AL MVP campaign of Roger Clemens to the postseason.

In the ALCS vs. the Angels, Boyd started Game 3 and allowed four earned runs over 6.2 innings, taking the loss in California’s 5-3 win. He returned to the mound in Game 6, the game after the Red Sox’s improbable rally kept them alive in the series. With Boston still trailing the ALCS 3-games-to-2, Boyd permitted just three runs over seven innings as the Red Sox won 10-4 to force Game 7. He allowed two runs in the top of the first inning, however, and was nearly knocked out of the box before getting Rob Wilfong to pop out to first base with the bases loaded to end the frame.

From there, Boyd allowed just one run.

“I wanted (Boyd) to get out of the first inning,” Red Sox manager John McNamara told Knight-Ridder News Service after the game. “He’s a little high-strung and hyper and nervous. But he was throwing the ball well.

“But I wasn’t going to let him stay out there if we were going to get in the hole right off the bat.”

The Red Sox went on to win Game 7, advancing to the World Series against the Mets. Boyd drew the start in Game 3 with Boston leading the series 2-games-to-0. But the Mets jumped on Boyd right away, scoring four runs in the first inning via a leadoff homer by Lenny Dykstra and RBI hits by Gary Carter and Danny Heep. Boyd would last seven innings, giving up six runs in Boston’s 7-1 loss.

In line to start Game 7 after the Mets’ historic comeback to win Game 6, Boyd was skipped in the rotation when rain postponed the final game by one day – giving Bruce Hurst – who had pitched so effectively in Games 1 and 5 – the chance to start Game 7 on three days’ rest.

After five shutout innings, Hurst allowed three runs in the sixth as the Mets tied the game before going on to win 8-5.

Media outlets reported Boyd took the news well about being skipped for Game 7. But later in his career, Boyd said he walked the New York streets for hours after learning he would not make the start.

“I was going to quit that day, turn in my uniform, give up baseball,” Boyd told The Boston Globe in 1994.

Instead, Boyd reported to Spring Training the following year in a good mood. But that quickly ended when a reporter asked him about a warrant issued for his arrest in 1986 that alleged Boyd did not meet his obligations for renting video equipment from a Winter Haven business. Boyd became enraged and knocked over a laundry cart.

The Red Sox could not repeat their AL pennant in 1987 – in no small part due to Boyd’s arm injury, which kept him sidelined until June and only allowed him to make seven starts the entire season. Described as a “knot” between his neck and shoulder, the ailment baffled doctors.

“It’s been impossible thus far to determine precisely what is wrong with Boyd,” Red Sox physician Dr. Arthur Pappas told United Press International in May.

Eventually, Boyd underwent surgery to repair a torn muscle.

“Scared? I’ll tell you I was scared,” Boyd told the Daily Hampshire Gazette in the spring of 1988. “I didn’t want any doctor with a knife cutting on my shoulder. But I was determined not to let it get me.”

But Boyd struggled in 1988, going 9-7 with a 5.34 ERA over 23 starts during a season where the Red Sox won the AL East title. He did not appear in a game after Aug. 26, including the ALCS vs. the Athletics, as the pain in his shoulder returned prior to landing on the disabled list with blood clots in the joint.

He then missed almost four months of action in 1989 – making five of his 10 starts of the season in September after medication appeared to solve the problem with the blood clots. He finished the season 3-2 with a 4.42 ERA and became a free agent before agreeing to a one-year, $550,000 deal with the Expos that included an option for 1991.

“Everybody has problems,” Boyd told the Canadian Press when he signed with Montreal. “No one’s perfect. It’s all water under the bridge. I have no regrets about my time in Boston.

“When I’m on, I’ll be the best pitcher that ever lived.”

Boyd might not have reached that standard, but he was very effective for the Expos in 1990 – going 10-6 with a 2.93 ERA over 190.2 innings. His peripheral numbers with the Expos were similar in 1991, though he went 6-8 with a 3.52 ERA through 19 starts before he was traded to the Rangers in a deadline deal for Joey Eischen, Jonathan Hurst and a minor leaguer. But with Texas, Boyd was 2-7 with a 6.68 ERA in 12 starts.

He signed with the Pirates in late April of 1992 and was sent to Triple-A Buffalo, but Boyd never appeared in a game with the Bisons. He pitched in Mexico, tried to catch on with the Indians in 1994 but failed to make the roster and then landed with the Northern League All-Stars – throwing the first pitch against the Colorado Silver Bullets women’s team.

“This don’t strike me as strange at all,” Boyd told The Boston Globe about his pitching against the Silver Bullets. “I’ve been here, there and everywhere.”

Boyd would pitch in the Northern League again in 1995 then switched to the Northeast League in 1996, where he went 10-0 with Bangor. He would play independent league ball again in 1997 before retiring to private business – but he returned in 2005 at 45 years of age to pitch for the Brockton Rox of the Canadian-American Association. In 17 appearances, he was 4-5 with a 3.83 ERA. At the time, the only members of the 1986 Red Sox still playing pro baseball were Roger Clemens and Oil Can Boyd.

“I’m blessed with this mystique,” Boyd told The Boston Globe when he was pitching with Brockton. “I got a nickname and I know how to pitch. And it seems like fans in this part of the country don’t say no to Can.”

Boyd finished his 10-year big league career with a record of 78-77, posting a 4.04 ERA over 214 appearances.

Few players of his era made more headlines – both good and bad – than Oil Can.

“Baseball got in me when I was little,” Boyd told the Courant in 1982 before he debuted in the big leagues. “It runs in my family, and it rubbed off on me. It’s a disease.

“I’m never going to get discouraged. Puzzled sometimes, but never down. Never.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum