- Home

- Our Stories

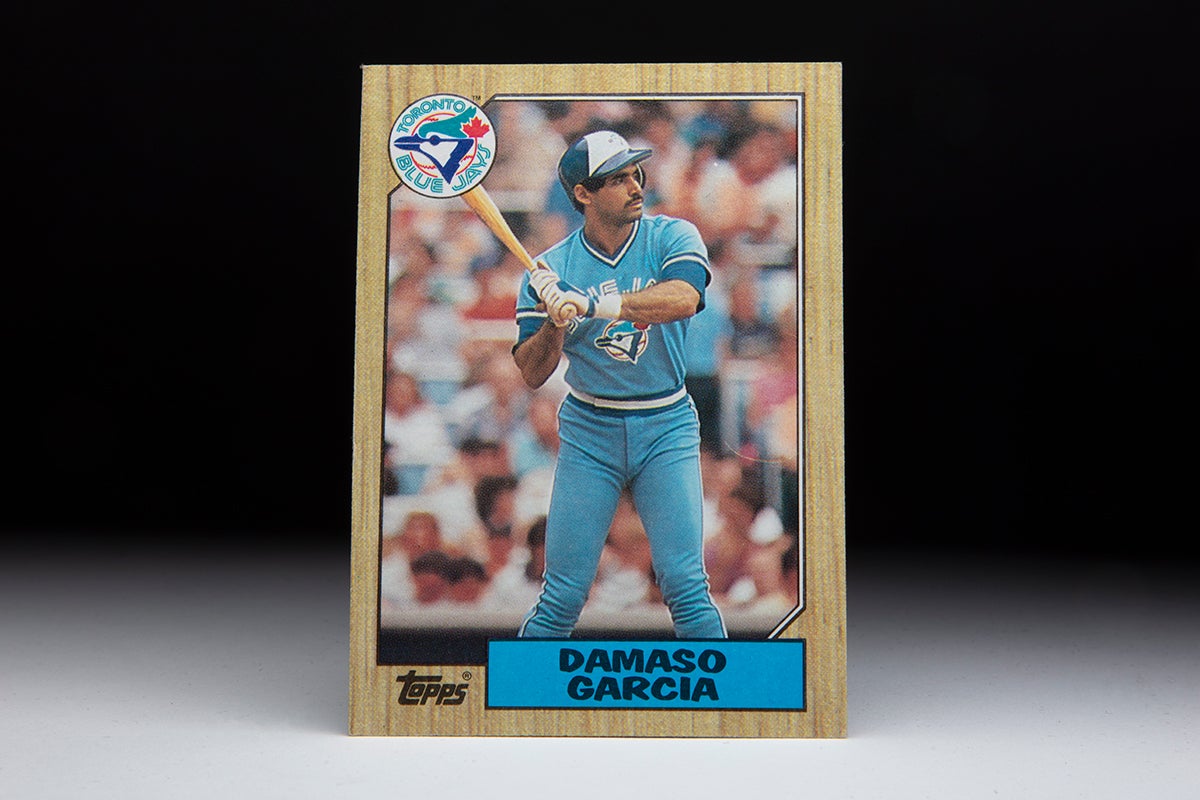

- #CardCorner: 1987 Topps Dámaso García

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Dámaso García

The Toronto Blue Jays that won back-to-back World Series titles in 1992-93 were the product of a careful build from the ground up by Hall of Fame executive Pat Gillick.

But many of the players who laid the groundwork for those championships were not around when the World Series rings were issued.

Dámaso García was one of those absent, having finished his career before the ultimate payoff.

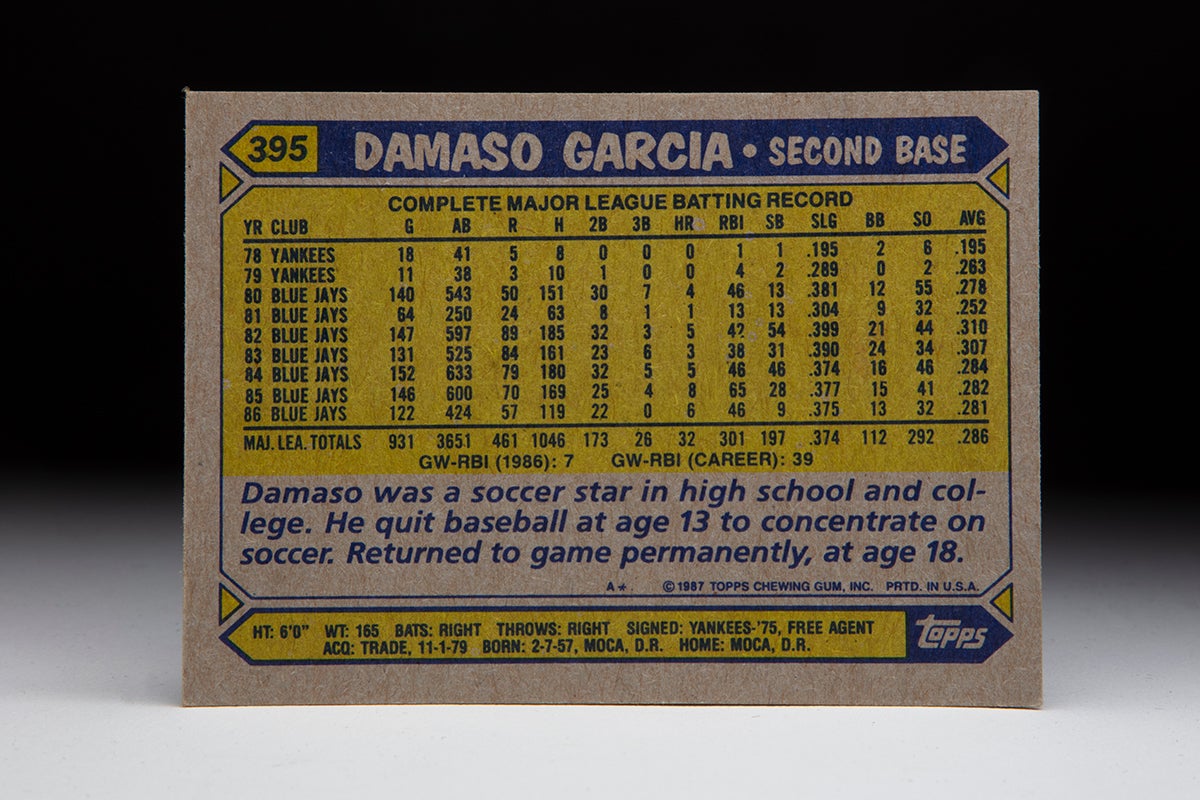

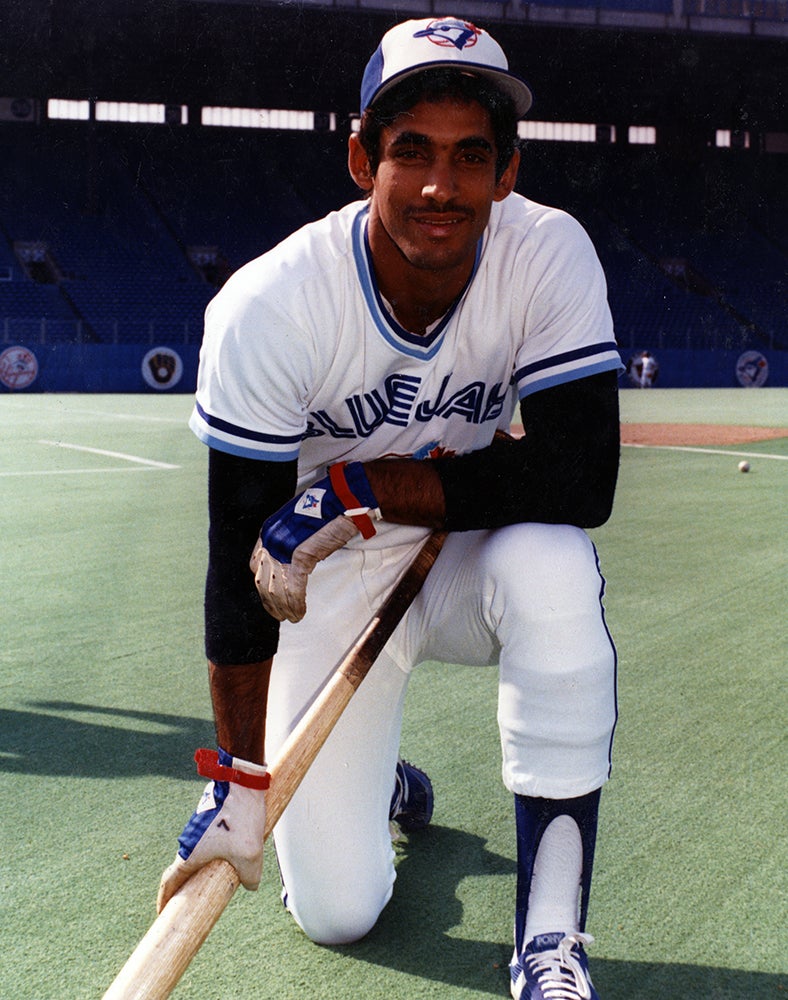

García was born Feb. 7, 1957, in Moca, Dominican Republic. The son of a church maintenance worker, García played baseball in grammar school but quit at age 13 to concentrate on soccer. Growing into his 6-foot-1, 165-pound frame, the athletic García received a college scholarship to play soccer and eventually captained the Dominican Republic’s national team.

But in the spring of 1975, García was playing sandlot baseball when he was spotted by legendary scout Epy Guerrero, then working for the Yankees. Within a week of a tryout under Guerrero’s watchful eye, García signed with the Yankees for a $6,000 bonus.

“I never imagined I would ever play professional baseball,” García told the New York Times News Service in 1984.

García would learn the game – and the English language – simultaneously in the United States.

“’I got it. I got it. I got it.’ My first words,” García told Newsday in 1978.

García reported to Oneonta, N.Y. (located about 30 miles from Cooperstown) of the New York-Penn League in 1975 and hit .268 in 50 games. A shortstop in amateur ball, García was moved to second base by the Yankees and began climbing the ladder toward the big leagues.

He batted .265 with 18 steals in 124 games for Class A Fort Lauderdale of the Florida State League in 1976 before moving to West Haven of the Double-A Eastern League a year later, where he again hit .265. He showed off his range at second base, totaling a league-best 382 assists and 664 total chances in 129 games.

Splitting time between second base and shortstop with Triple-A Tacoma in 1978, García hit .268 while matching his RBI total from 1977 with 53.

Mike Ferraro, a former big league infielder who went on to skipper the Indians and Royals in the 1980s, managed García at each of his minor league stops – moving up with his prized pupil.

“Ferraro helped (me) a lot,” García told the Tacoma News Tribune in 1978, “in every way, physical and mental.”

When Yankees All-Star second baseman Willie Randolph was sidelined with a knee injury in June of 1978, García was called up to the big leagues. He had two hits and three runs scored in his second big league game on June 25 but committed a costly error the next day that helped the Red Sox beat the Yankees 4-1. The loss dropped the Yankees to nine-and-a-half games behind the Red Sox in the American League East standings, and Yankees manager Billy Martin – less than a month away from being dismissed from his job – blamed García for the defeat.

García appeared in 18 games while Randolph was sidelined and hit .195 before being returned to Triple-A. Randolph was injured again at the end of the season and did not play in the postseason after the Yankees won the AL East by defeating the Red Sox in a one-game playoff. But new manager Bob Lemon chose to go with Brian Doyle – who was almost four years older than García – at second base rather than García, and Doyle responded by batting .438 in the World Series as the Yankees won their second straight championship.

García, however, was clearly one of the top prospects in the New York farm system. And many in the Yankees organization believed that García was the team’s shortstop of the future. But with All-Stars Bucky Dent and Randolph handling shortstop and second base, respectively, there was little room for García in the lineup.

García was sidelined for much of the 1979 season with a broken bone in his left hand and played in only 39 games for Triple-A Columbus, hitting .271. He was called up to the big leagues in September and played in 11 games, mostly at shortstop, hitting .263.

Then on Nov. 1, the Yankees executed a blockbuster deal with the Blue Jays, acquiring Rick Cerone, Tom Underwood and Ted Wilburn from Toronto in exchange for Chris Chambliss, Paul Mirabella and García. The trade was New York’s response to losing catcher and team captain Thurman Munson in a fatal plane crash during the 1979 season, with Cerone expected to step in at catcher.

García, meanwhile, was the key return for the Blue Jays.

“The reports on Dámaso García indicate he has a chance to be an outstanding infielder,” Blue Jays manager Bobby Mattick told United Press International.

Meanwhile, García recognized that the trade gave him the chance to display his talent.

“I was glad to go,” García said of the trade to the Blue Jays. “I wanted the opportunity to play every day.”

García got that chance in 1980, earning the Opening Day start at second base and batting .278 with 30 doubles, 46 RBI and 13 steals in 140 games. He finished third among AL second basemen with 471 assists and graded out well defensively despite committing 16 errors.

Combining with Alfredo Griffin on the Blue Jays’ double play team, García finished fourth in the AL Rookie of the Year balloting.

“(García) has been driving the ball a little harder and getting more extra base hits than we expected,” Gillick told the Toronto Star. “Overall, I would say he has probably done better than we could expect for his first season.”

Mattick was even more effusive in his praise of García, comparing him to Hall of Famers Bill Mazeroski and Billy Herman, who Mattick rated as the best second basemen he had seen at turning the double play.

“García can get more on the ball on his throws than either one of them,” Mattick told the Toronto Star in 1980.

García battled nagging injuries in 1981 and never got untracked at the plate, batting .252 over 64 games in that strike-shortened season. But he recovered his 1980 form and more in 1982, batting .310 with 32 doubles, 89 runs scored and 54 stolen bases en route to a Silver Slugger Award and some down-ballot support in the AL Most Valuable Player voting. New manager Bobby Cox installed García as his leadoff hitter, and García set team records for steals, runs and hits (185).

“I saw Dámaso when he started in the minors,” said Cox, who worked in the Yankees organization in the 1970s. “It was clear then that he had great natural ability and that all he needed was polishing. Now he is polished, so you just let him play. His running and fielding are as good as his hitting.”

Prior to the start of the 1982 season, García had reached a two-year agreement worth a reported $330,000 with the Blue Jays. But after representing himself in those negotiations, he changed his mind about the deal before the season began, hired an agent and did not sign his one-year deal (worth about $90,000) until two months into the campaign, refusing to accept his first two paychecks of the season.

The negotiations would set the tone for some acrimonious contract discussions in subsequent years.

García filed for arbitration after the 1982 campaign, asking for $400,000. He won his case but was incensed at how the Blue Jays presented their facts when arguing that García should only be paid $300,000.

“They didn’t take Dámaso García the player to arbitration,” García told the Toronto Star in the days before the case was decided. “They took Dámaso García the person. They say I don’t work hard. They say I’m below average.”

García asked to be traded following the hearing, and throughout the 1983 season he was rumored to be on the move to several teams. But Gillick held firm as García hit .307 with 23 doubles, 31 steals and 84 runs scored in 131 games.

On Valentine’s Day of 1984, García signed a five-year deal with the Blue Jays worth about $3.5 million.

García continued his productive ways at the plate in 1984, earning his first All-Star Game selection while hitting .284 with 32 doubles, 79 runs scored and 46 steals.

“Dámaso is fun to watch,” Blue Jays teammate Dave Collins said in 1984. “He’s the only hitter I’ve ever seen who can swing at balls over his head or in the dirt and still get base hits.”

But despite his numbers and his contract, trade rumors continued to swirl due to the presence of prospect Tony Fernández, who was pushing Griffin and García for playing time.

García was also the target of criticism for his aggressive approach at the plate. He drew just 16 walks in 1984 after setting a career-best with 24 the year before.

“They said I didn’t walk enough,” García told the Toronto Star during his contract dispute with the Blue Jays in 1983. “They consider a walk like a single, but that thinking was a long time ago. You can’t move a man from second with a walk.”

In the end, Gillick decided to keep García and pair him with Fernández at shortstop, sending Griffin to the Athletics with Collins on Dec. 8, 1984, in exchange for reliever Bill Caudill.

“That guy,” Blue Jays coach Cito Gaston told the New York Times News Service about García in 1984, “you just try to leave his hitting alone.

“Dámaso almost wraps the bat around his head at the plate. We’ve talked about changing his stance but we don’t want to take away any of his aggressiveness. He’s a free swinger.”

And García continued to put up solid defensive numbers, finishing fifth among AL second basement in 1984 with 427 assists.

“Because he’s such an offensive threat, people tend to forget his defense,” Blue Jays first base coach Dave Nelson told the New York Times News Service in 1984. “But he has tremendous range and ranks with Frank White and Julio Cruz at the top of the league.”

In 1985, the Blue Jays put it all together and won the AL East, with García at the top of a potent lineup that featured George Bell, Lloyd Moseby and Jesse Barfield as well as Fernández. García hit .282 with 28 steals and 65 RBI in 146 games, earning his second All-Star Game selection and once again getting support in the AL MVP race.

Playing in the postseason for the first time, García recorded seven hits and four runs scored over seven games, igniting a three-run Blue Jays rally in the ninth inning of Game 4 with a leadoff walk. Those runs turned a 1-0 deficit into a 3-1 win over the Royals that gave Toronto a 3-games-to-1 lead in the series. But the Blue Jays lost the next three games as Kansas City advanced to the World Series.

Those seven games would prove to be the beginning of the end of García’s career in Toronto and the big leagues.

In 1986, Cox left to join the Braves’ front office and was replaced by Jimy Williams, who made plans to drop García to the ninth position in the batting order and move Moseby to the top spot.

“Dámaso’s legs have bothered him,” Williams told the Orlando Sentinel during Spring Training. “If he hits leadoff, he’ll feel like he has to steal. I only did it so he could stay in the game longer and help us.”

García immediately asked to be traded “even if it’s to Cleveland.”

“You call that freedom of speech,” Williams said. “But I still want Dámaso in my lineup.”

But Williams’ feelings changed during a season where García feuded with teammates Ernie Whitt and Barfield, set fire to his uniform following a 6-3 loss to the Athletics on May 13 and got into a batting cage skirmish with teammate Cliff Johnson before a game against the Royals in August.

“So I burned my uniform,” García told the Ottawa Citizen following the season. “It’s like I’m probably going to the Hall of Fame, they made such a big deal about it.

“I don’t see myself (with Toronto) next season.”

García proved to be correct when the Blue Jays traded him and pitcher Luis Leal to the Braves on Feb. 2, 1987, in exchange for Craig McMurtry. But García did not play in any regular season games that year after undergoing knee surgery on March 31.

García was the Braves’ Opening day second baseman in 1988 and had three hits in a 13-inning loss to the Cubs. But he soon entered a prolonged slump and was eventually benched in favor of Ron Gant. He then grumbled about playing different positions and his new bench role.

On May 17, the Braves released García.

“He was out a whole year,” Braves manager Chuck Tanner told the Atlanta Constitution. “It’s hard to come back after that.

“The injuries were unfortunate. I don’t know how much they took from him, but they took a lot.”

García signed with the Dodgers about a month after being released but appeared in only three games for Triple-A Albuquerque before being cut loose. He signed with the Expos a month before Spring Training in 1989, spending the season as a utility player and hit .271 in 80 games in that role.

A free agent again after the season, García signed with the Yankees but was released during Spring Training.

“B.J. Birdy, or whatever the (heck) that (Toronto) mascot’s name was, has a better chance of becoming a manager or a coach that I do,” García told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1990 about his prospects for getting back into the game. “Because I have a big mouth. Or, at least, people in baseball think I have a big mouth.”

In 1991, García was beset by double vision and was eventually diagnosed with a brain tumor. He underwent surgery in Toronto in July of 1991 and then endured chemotherapy, eventually recovering enough to throw out the first pitch at Game 1 of the 1992 ALCS between the Blue Jays and Athletics.

“I couldn’t believe it,” the 35-year-old García told the Toronto Star when he was asked to throw out the first pitch. “I can’t describe the feeling. I thought it was a joke at first. It’s such a nice honor.

“My heart wants to play. But my health won’t let me. I feel like I’ve been through a war.”

Told after his surgery he had only six months to live, García survived almost 30 years after the procedure before passing away on April 15, 2020. He finished his 11-year big league career with a .283 batting average, 1,108 hits and 203 steals – and a legacy of dancing to his own beat.

“I hit my own way,” García said. “You have to feel comfortable at the plate.

“I’m aggressive. I just go up there and take my hacks. I don’t walk.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum