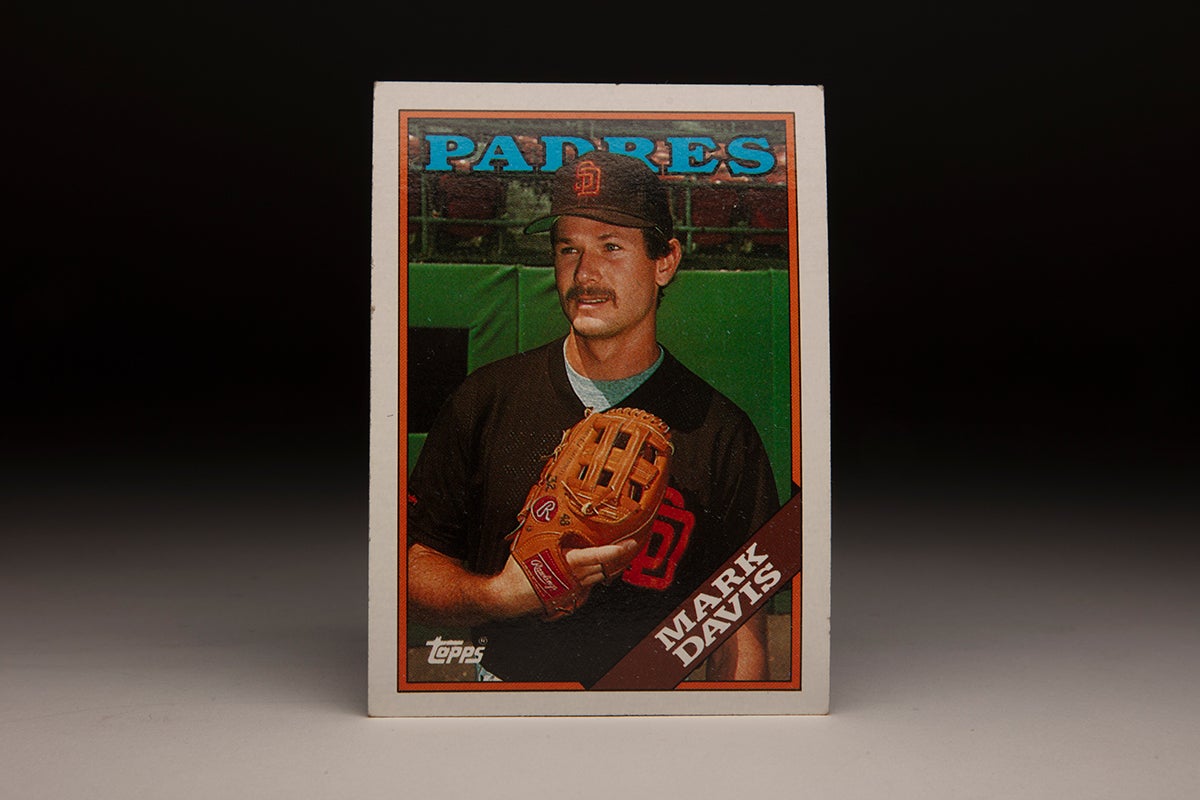

#CardCorner: 1988 Topps Mark Davis

Mark Davis pitched 15 years in the big leagues, never winning more than nine games in a season and totaling just two campaigns where he had at least 10 saves.

But in those two seasons, Davis may have been the most unhittable pitcher in the game who was not named Nolan Ryan.

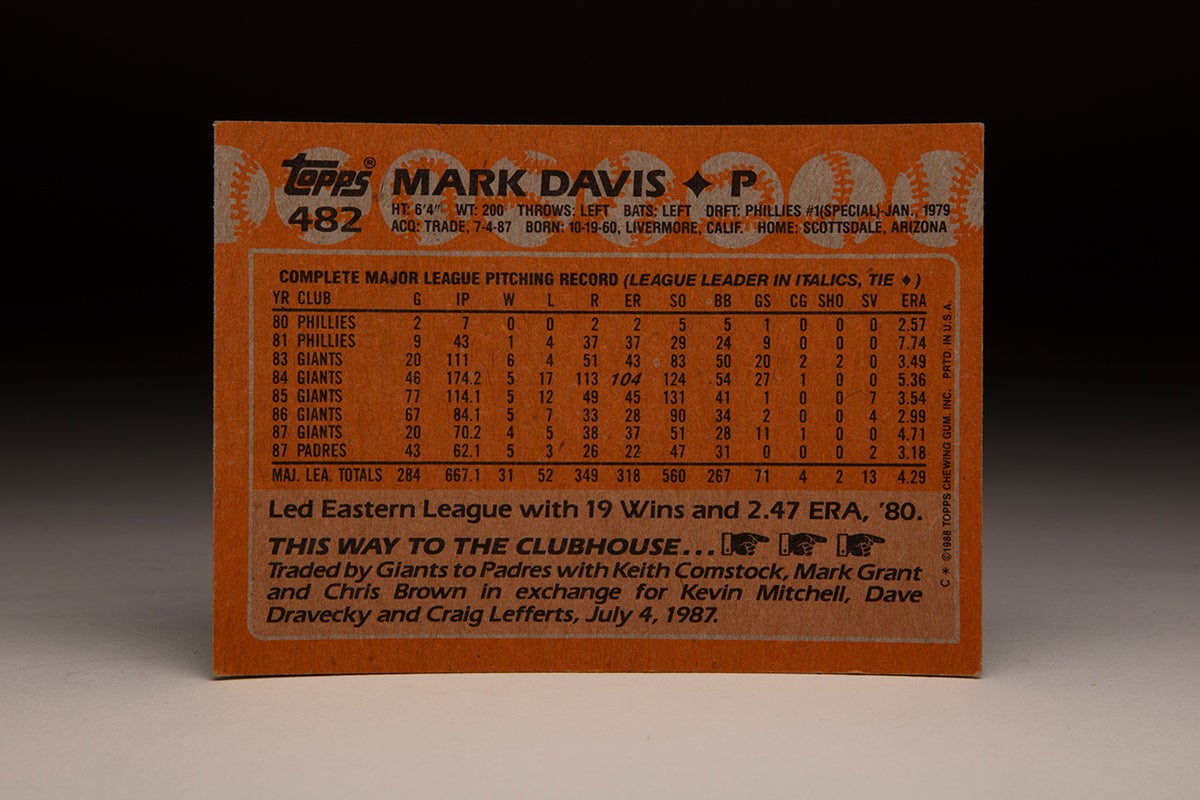

Born Oct. 19, 1960, in Livermore, Calif. – where another flame-throwing lefty, future Hall of Famer Randy Johnson, would come of age – Davis was a 22nd-round selection of the Mets in the 1978 MLB Draft but opted to enroll at Chabot College in Hayward, Calif., on the Oakland side of San Francisco Bay. He quickly established himself as a top prospect and was selected by the Phillies as the No. 1 overall pick in the January 1979 MLB Draft – a process designed to quickly get college players into the pro ranks.

Reporting to Class A Spartanburg of the Western Carolinas League, the 18-year-old Davis went 11-9 with a 3.20 ERA and 135 strikeouts over 166 innings as a starter. The next year, Davis became the talk of the minors while going 19-6 with a 2.47 ERA for Double-A Reading, striking out 185 batters in 193 innings.

His explosive fastball, knee-buckling curve and effective change-up convinced the Phillies that he could help the team in their National League East race with the Expos, and Davis made two appearances down the stretch – including starting the final game of the season against Montreal the day after Philadelphia clinched the division title.

Though he was not included on the Phillies’ postseason roster, Davis nonetheless contributed to a team that eventually won the first World Series title in franchise history.

Davis was the Eastern League Most Valuable Player in 1980 and earned a spot on the Topps Double-A All-Star team. But in the spring of 1981, Davis developed tendinitis in his throwing arm and was sent to Triple-A Oklahoma City. There, Davis went 5-2 with a 3.88 ERA but worked out his arm problems when pitching coach Cot Deal helped him identify a flaw in his mechanics.

“There was a period there where we really couldn’t do anything,” Deal told the Philadelphia Daily News. “But when he was able to throw again, we got him on the sidelines and went to work correcting the problem.

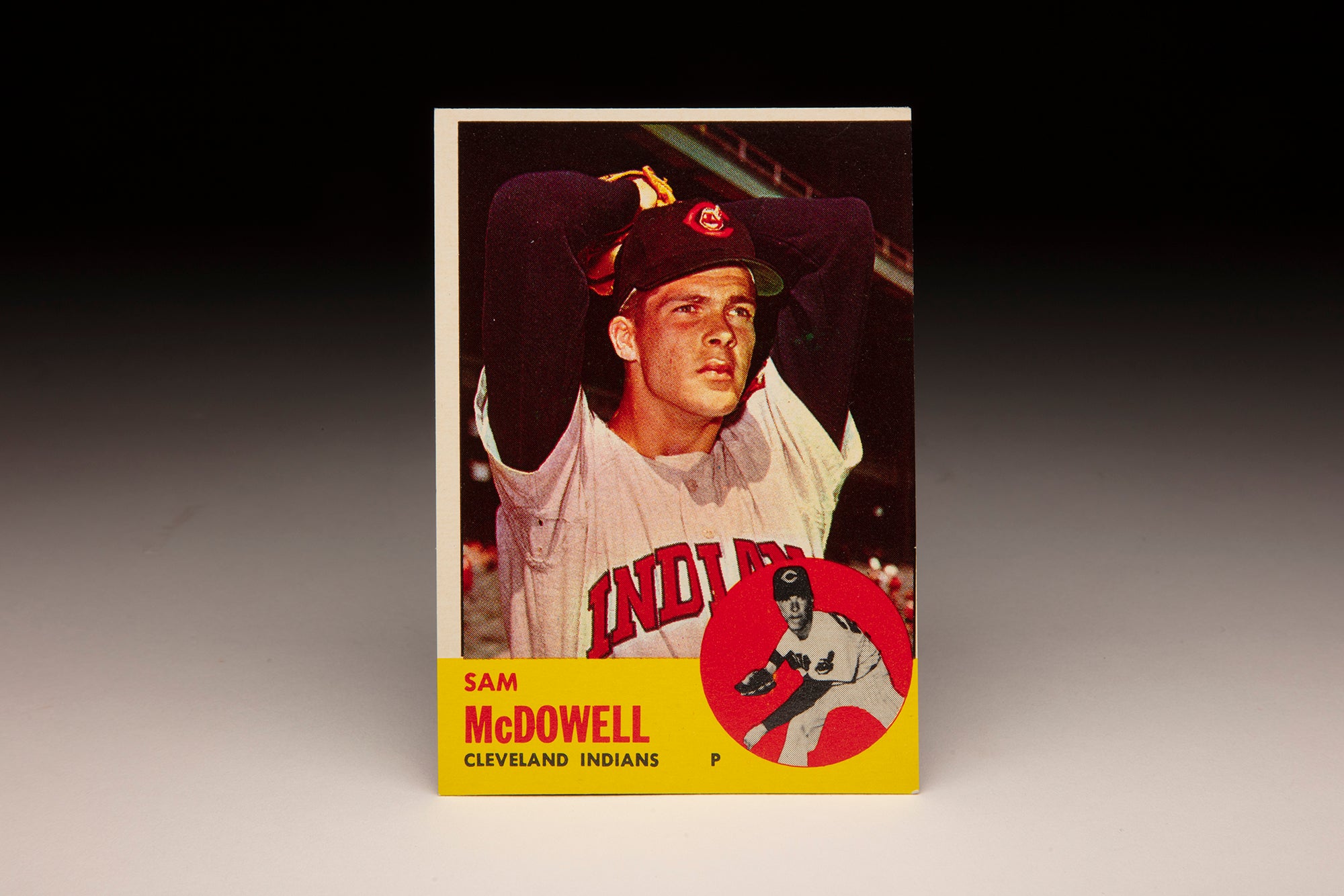

“When Mark Davis is right, he has outstanding stuff. I’ve seen Steve Carlton. I’ve seen Sam McDowell. I’d say Mark has that kind of ability.”

The Phillies brought Davis to the majors in August, but his first start was a disaster. He allowed seven runs in one-plus innings against the Braves, surrendering four hits and four walks Aug. 25 at Veterans Stadium. But the Phillies kept him in the rotation, and he made nine starts in the season’s final six weeks, picking up the first win of his career Sept. 24 vs. the Cardinals.

Davis finished the season with a 1-4 record and 7.74 ERA, striking out 29 batters over 43 innings. Once again, he was not included on the postseason roster – denying Davis what would turn out to be his best chance at pitching in the playoffs.

“He isn’t a pitcher yet; he’s being led,” Phillies manager Dallas Green told the Philadelphia Inquirer after Davis surrendered six runs in 5.1 innings in a 7-0 loss to the Mets on Sept. 29, 1981, as the Phillies were preparing for the NLDS. “He has to take more charge of his stuff on the mound, be a lot more aggressive out there and go after hitters better. I know he’s 20 years old, and sometimes that’s asking a lot. But we’re in a business where we ask a lot at this level.”

While with the Phillies, Davis was often compared to young versions of Sandy Koufax and Steve Carlton – a level that neither he nor virtually anyone else could reach.

“If Mark Davis is not trying to be what he is, if he’s trying to be Steve Carlton or somebody, he’s making a big mistake,” Mets lefty Pete Falcone, who was once compared to Koufax, told the Inquirer. “It’s easy to start trying to be somebody you’re not if they put that kind of pressure on you.”

Davis entered Spring Training in 1982 as the presumptive fifth starter for the Phillies. But after struggling in March, Davis was among the Phillies’ final cuts and was sent back to Triple-A.

With Oklahoma City, Davis’ star lost much of its luster as he went 5-12 with a 6.24 ERA and 95 strikeouts over 96.2 innings. He did not pitch in the majors during the entire season.

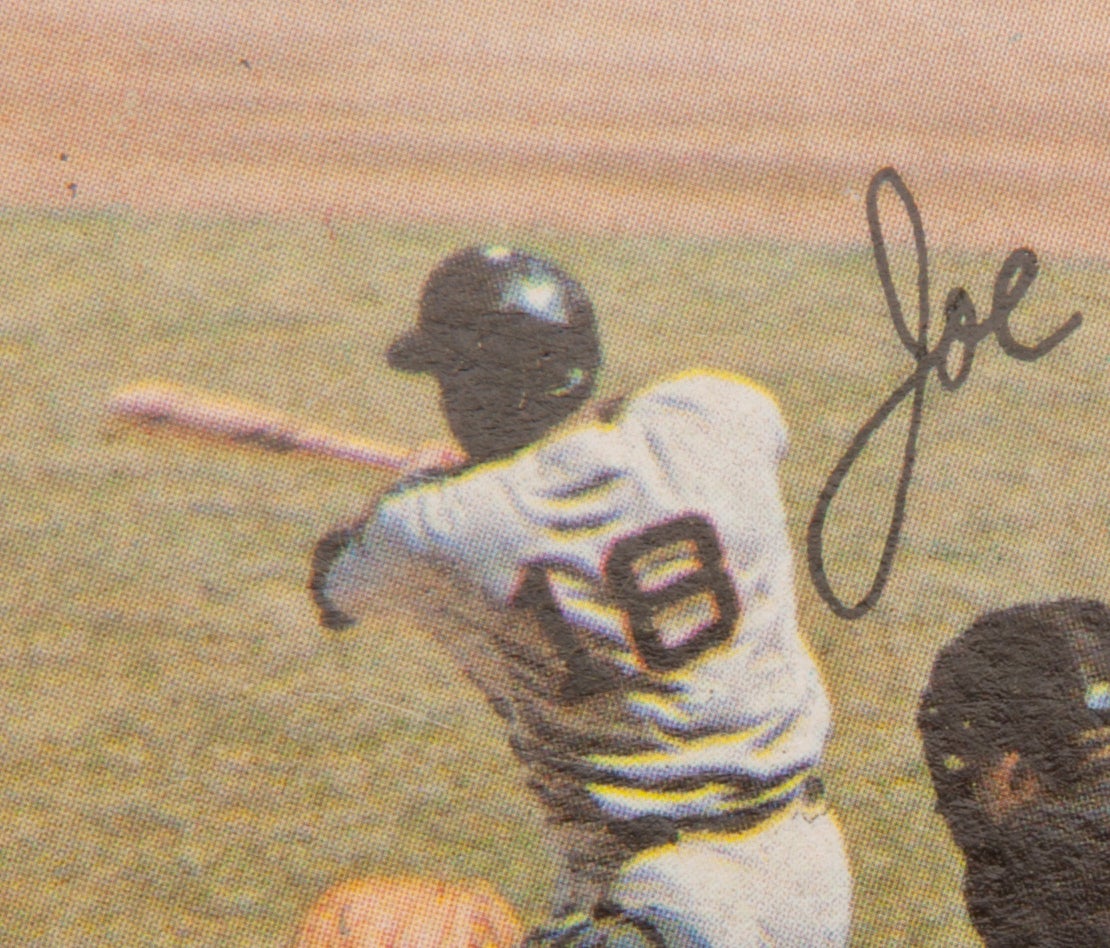

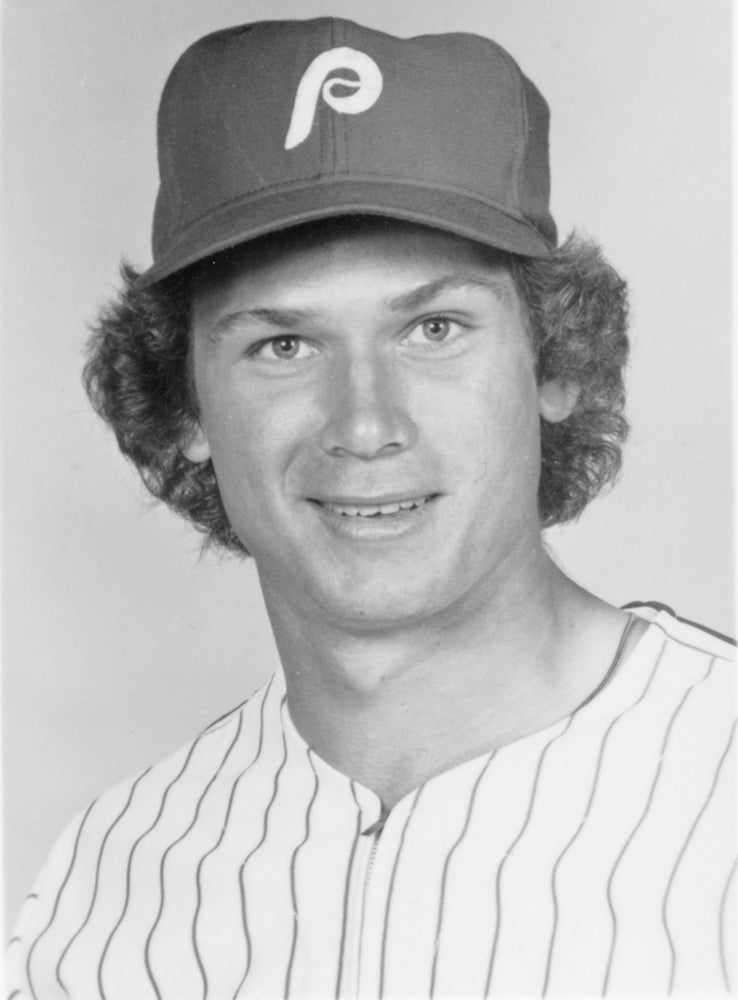

On Dec. 14, 1982, the Phillies packaged Davis, Mike Krukow and a minor leaguer and sent them to San Francisco in a deal for Al Holland and Joe Morgan. The trade gave the Phillies the pieces they would need en route to their 1983 NL pennant.

Meanwhile, Krukow was the main target for the Giants.

“We’re confident Mike (can stabilize the team’s young rotation),” Giants general manager Tom Haller told the Associated Press.

The Giants sent Davis to Triple-A Phoenix to begin the season, and Davis continued to struggle – going 6-3 with a 6.32 ERA and 64 strikeouts in 72.2 innings. But the Giants had a hard time finding a consistent fifth starter that year and turned to Davis in June.

After a couple rough outings, Davis flashed his immense potential on July 30 when he shut out the eventual NL West champion Dodgers on seven hits – notching his first win with San Francisco and becoming the first Giants pitcher to blank L.A. since Ed Halicki in 1976.

“When I thought of playing Major League Baseball, I always envisioned being on the Giants and going out to pitch against the Dodgers,” Davis told the Associated Press. “I pitched well enough to win before. You win some and you lose some. I happen to be on the short end of the stick a lot of times.”

Davis remained in the rotation for the rest of the year, shutting out the Dodgers again on two hits on Sept. 16 and finishing with a 6-4 record and 3.49 ERA in 20 starts. That performance earned him the nod as the Giants’ Opening Day starter in 1984, but the season quickly deteriorated for Davis as he lost his first five decisions, endured a nine-game losing streak in July and August before being sent to the bullpen and finished the season 5-17 with a 5.36 ERA and an NL-worst 104 earned runs allowed.

Davis worked on his craft in winter ball following the season, and the Giants hinted that they might send him to the bullpen going forward. When lefty relief ace Gary Lavelle was traded to the Blue Jays on Jan. 26, 1985, Davis saw the writing on the wall.

“About 10 days ago, (Giants general manager Tom) Haller sat me down and said: ‘Look, you’re our short left-handed reliever. Just go out there and throw strikes,’” Davis told the Peninsula Times Tribune on March 27, 1985. “I think I can pitch in any role they put me in. I don’t think because I had a bad year last year doesn’t mean I can’t start. But I want to try (pitching in relief) before I say I prefer starting.”

With that one move, the Giants found a reliever – and Davis found his future.

Davis appeared in a team-high 77 games in 1985 – one short of NL leader Tim Burke of the Expos – and went 5-12 for a Giants team that lost 100 games. But he saved seven games, posted a 3.54 ERA and struck out 131 batters in 114.1 innings.

Davis was even better in 1986, going 5-7 with a 2.99 ERA and four saves in 67 games. After avoiding arbitration by signing a one-year deal worth $415,000 for the 1987 season, Davis – like many of the Giants pitchers under manager Roger Craig – began experimenting with a split-fingered fastball. The Giants believed the pitch gave Davis enough variety to rejoin the rotation, and Davis started the team’s fourth game of the season. But after posting a 4.08 ERA over seven starts, Davis returned to the bullpen before another short stint in the rotation in June.

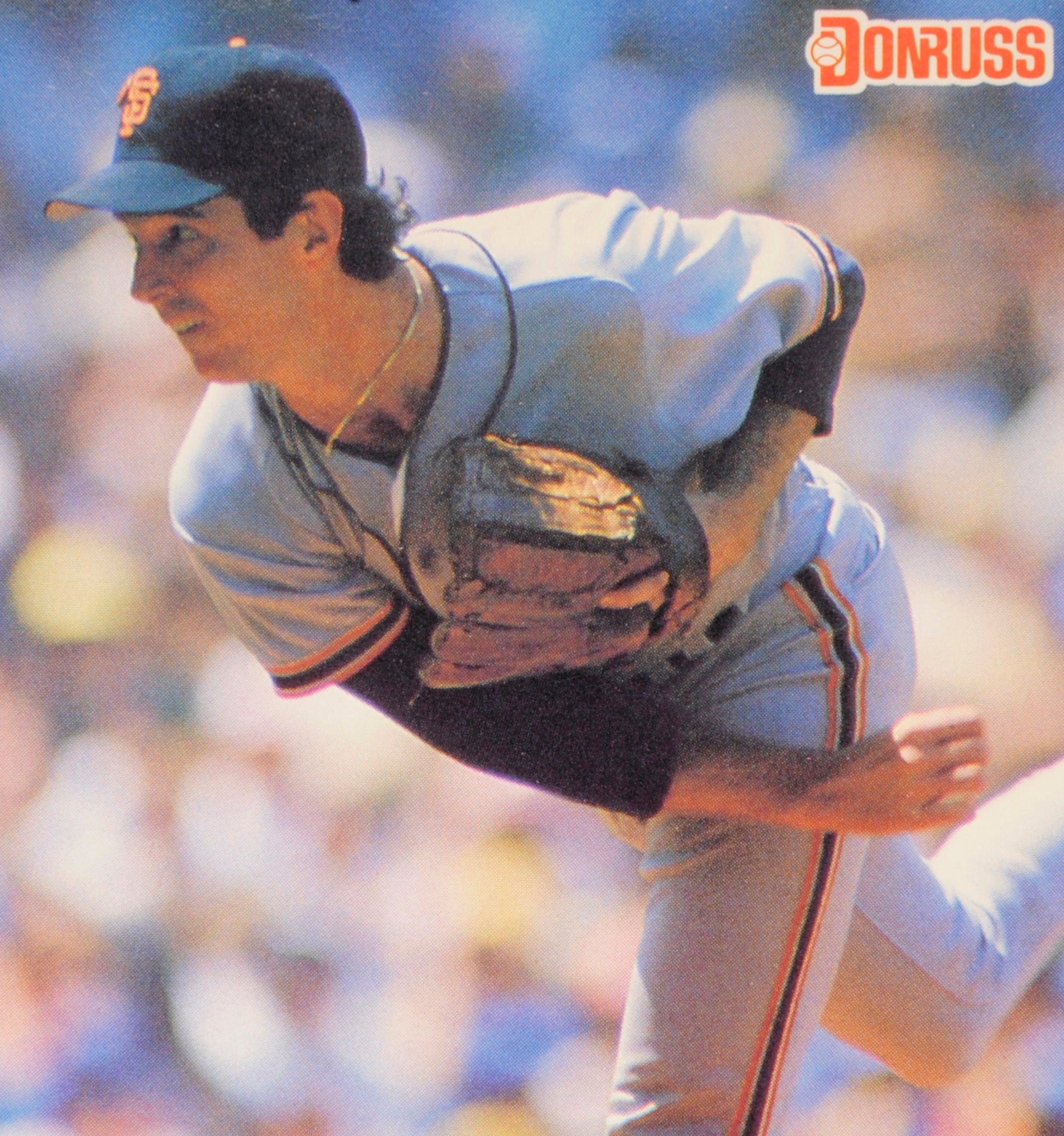

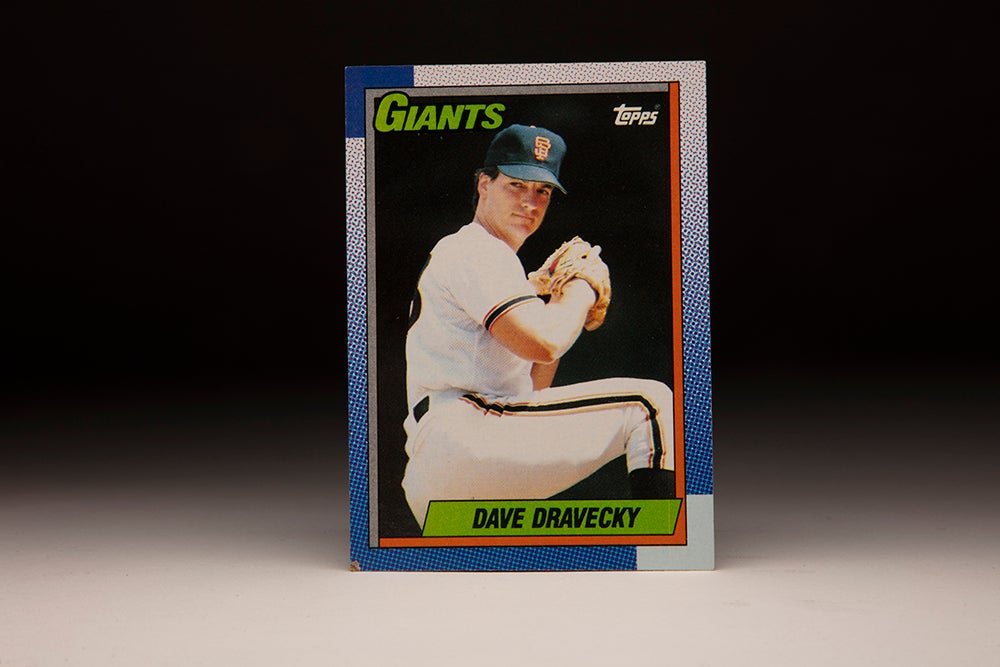

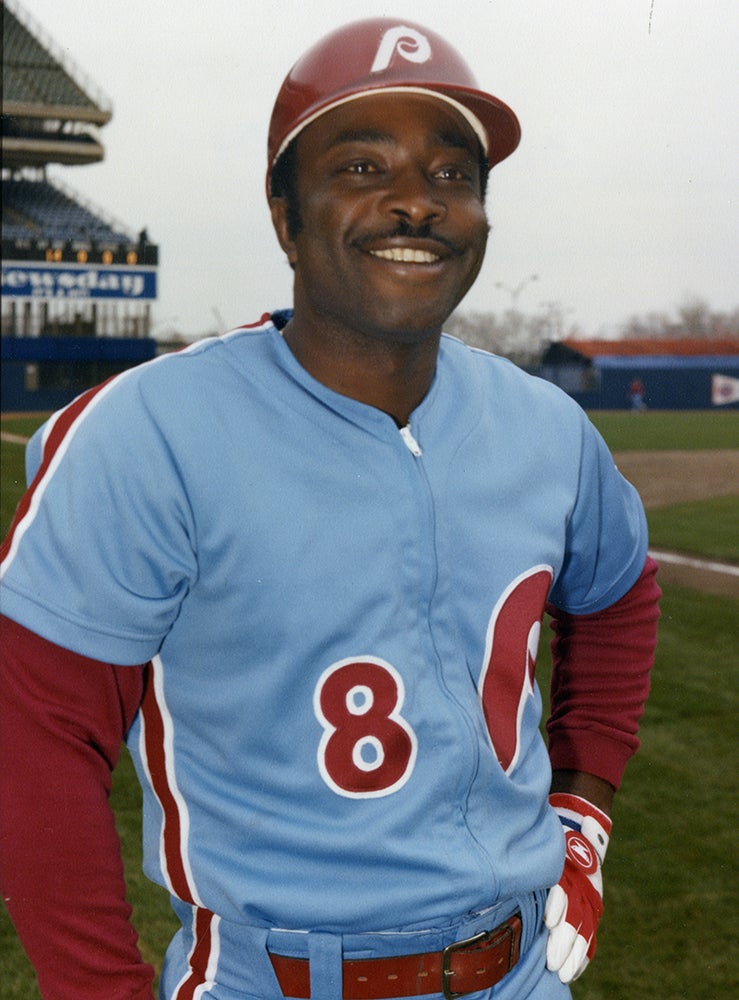

On July 5, 1987, with the Giants challenging for the NL West title, San Francisco sent Davis, Chris Brown, Keith Comstock and Mark Grant to the Padres in a deal for Dave Dravecky, Craig Lefferts and Kevin Mitchell.

The trade would power the Giants to the NL West crown, and Mitchell would go on to win the 1989 NL Most Valuable Player Award. Davis, meanwhile, would become the game’s best relief pitcher.

“I think he was in the doghouse over there and just wants a chance to pitch,” Padres manager Larry Bowa told the Los Angeles Times about Davis, who had drawn criticism from Craig during the 1987 season. “(Davis)…will get every chance to get batters out from both sides of the plate.”

Davis returned to the bullpen with San Diego and recaptured his form, going 5-3 with two saves and a 3.18 ERA over 43 games. In 1988, Davis started the season as the Padres’ primary set-up man with Lance McCullers in the closer’s role. But the two soon traded places, and Davis reeled off eight saves in June en route to 28 on the season to go along with a 5-10 record and 2.01 ERA in 62 games. Davis was also named to his first All-Star Game, working two-thirds of an inning in a season where he pitched 98.1 frames in the regular season, often enduring multiple-inning stints.

The stage was then set for Davis’ 1989 season, where he notched a big league-best 44 saves in 48 opportunities, went 4-3 with a 1.85 ERA and struck out 92 batters in 92.2 innings. An All-Star for the second straight season, Davis easily won the NL Cy Young Award by earning 19 of 24 possible first-place votes, outdistancing runner-up Mike Scott of the Astros by 42 points.

Davis permitted just 6.4 hits per nine innings pitched, the same mark he allowed in 1988. If he had pitched enough innings to be eligible for the league leaderboard, Davis would have finished just behind José DeLeón of the Cardinals for the league lead in that category in 1989.

It was perfect timing for Davis, who became a free agent two weeks before he was named the Cy Young Award winner.

“A lot will go into the decision (on where he will sign),” Davis told the AP after becoming the seventh relief pitcher to win a Cy Young Award. “But today, I feel this is a happy time for the Padres and myself…and I would like to focus on that.”

Davis had reportedly already turned down a three-year, $7 million offer from the Padres. On Dec. 11, Davis made that decision look smart by agreeing to a four-year, $13 million deal with the Royals.

He said it was the “fifth-best” offer in terms of money that he received.

“It was not a matter of money,” Davis told the Baltimore Evening Sun. “I took into account that Kansas City is a most consistent organization, and the way my family felt. I did not take the highest bidder. I took the one that’s best for Mark Davis and my family.”

Davis’ contract called for him to receive an annual salary of $3.25 million in each season from 1991-93 – which at the time was the top single-season number in baseball.

The contract, however, proved to be disappointing for all parties. Davis went 2-7 with six saves and a 5.11 ERA in 1990, losing his spot as the team’s closer to Jeff Montgomery in May. Montgomery finished the season with 24 saves, and the Royals had no interest in going back to Davis as closer in 1991.

The Royals did bring in Pat Dobson, the Padres’ pitching coach in 1989 when Davis won the Cy Young Award, to try to help Davis in 1991 – and Dobson immediately adjusted Davis’ mechanics back to the 1989 version.

But Davis was still trying to get right mentally after a stressful 1990 campaign.

“We’ve had long talks about what he’s thinking out there,” Dobson told Knight-Ridder Newspapers in the spring of 1991. “I’ve told him not to construct a problem in his mind before it ever happens. I’ve told him he has to let his ability take over. He wasn’t doing that last year.”

But 1991 proved no better as Davis went 6-3 with a 4.45 ERA in 29 games, making five starts while missing time with a fractured index finger. Montgomery, meanwhile, saved 33 games en route to 12 seasons with Kansas City that saw him amass 304 saves.

Davis began the 1992 campaign in the rotation but was sent to the bullpen after compiling a 9.60 ERA in four starts. On July 21, the Royals traded Davis to the Braves in exchange for Juan Berenguer. He pitched in 14 games for Atlanta that season, mostly in mop-up roles, and finished the season with a 2-3 record and 7.13 ERA in 27 games. He was not included on the NL West-champion Braves’ postseason roster.

Entering the final year of the contract he signed with the Royals, Davis was traded back to the Phillies on April 13, 1993, in exchange for a minor leaguer. The Phillies, Braves and Royals each paid portions of the $3.25 million salary Davis was owed that year.

The Phillies players welcomed the news, interpreting the deal as a sign the team was serious about winning.

“I think there was just a lot of pressure on him after he signed that contract,” Phillies first baseman John Kruk told the Philadelphia Daily News after the trade. “When he’s having fun, he can be an effective pitcher. If he doesn’t, we’ll kill him.”

Kruk, always fast with a witty line, quickly amended his promise.

“No, really, he’ll be welcomed here with open arms,” Kruk said. “I honestly think he’s going to help this team.”

But while the Phillies had a magical year in 1993 – winning the NL pennant – Davis did not. After going 1-2 with a 5.17 ERA in 25 games, the Phillies released Davis on July 2. He signed with the Padres eight days later and pitched in 35 games, going 0-3 with four saves and a 3.52 ERA to finish the season with 60 appearances.

Davis returned to the Padres in 1994, working in 20 games with an 8.82 ERA before drawing his release on May 24. After finding no offers immediately after the end of the work stoppage in the spring of 1995, Davis signed with the Marlins on July 30 but only pitched in the minors that year.

He did not pitch at all in 1996 but returned in 1997 on a minor league deal with the Diamondbacks (who would not begin their first MLB season until 1998), appearing in 33 games at the Class A and Triple-A levels before being traded to the Brewers in August. Davis made 19 relief appearances in Milwaukee in the final pro games of his career.

“I feel a lot better,” Davis told the Kansas City Star that fall, “than I have in five or six years.”

Davis finished his career with a record of 51-84 and 96 saves over 624 games. He struck out 1,007 batters over 1,145 innings.

And though he did not become the next Steve Carlton or Sandy Koufax, Mark Davis did collect the same hardware when he won the 1989 NL Cy Young.

“Until I hurt my arm (in 1981), everything was like a dream,” Davis told the Daily News in 1982. “I’d go out and pitch and really blow people away. I didn’t have any problems with anybody.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum