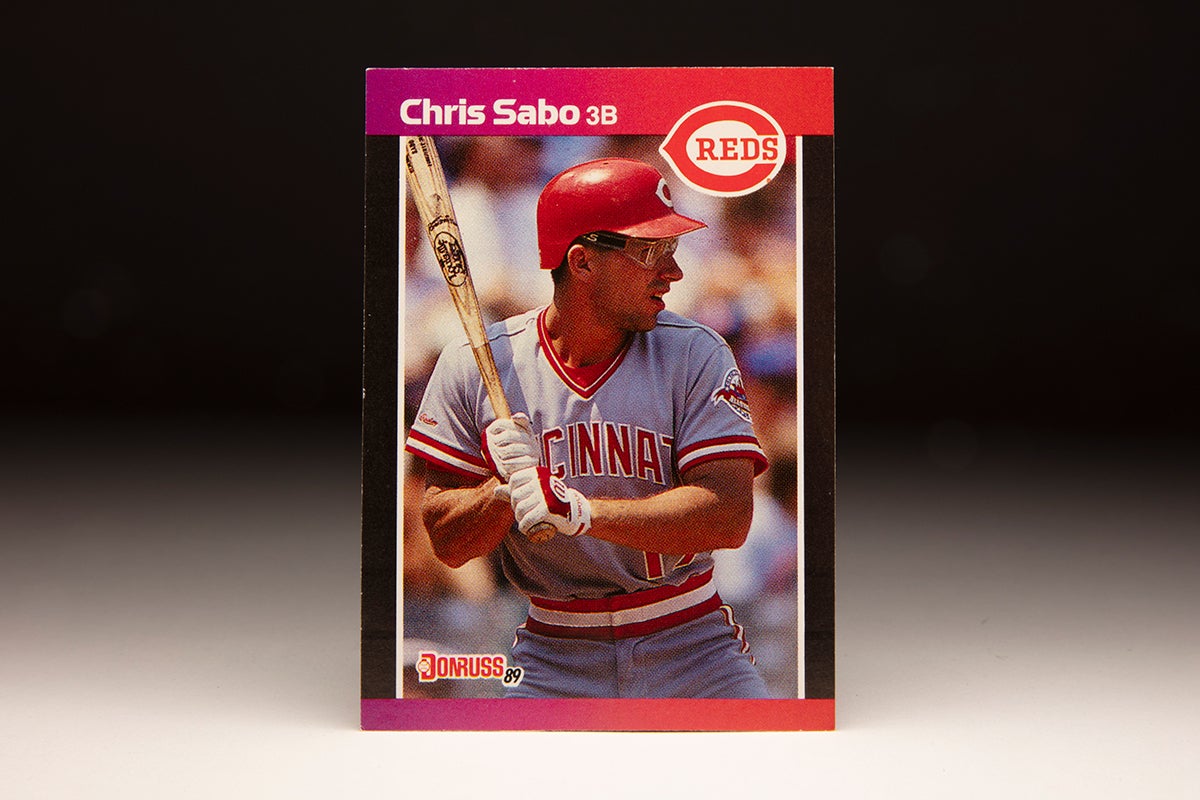

#CardCorner: 1989 Donruss Chris Sabo

Chris Sabo became an overnight sensation in 1988 with his hustle, speed and Rec Specs. Two years later, he batted an astounding .563 in the World Series to help the Cincinnati Reds win the title.

It would be the peak of a nine-year career that would see Sabo become a fan favorite in the Queen City.

Born Jan. 19, 1962, Sabo grew up in Detroit. Playing hockey in the winter – he was a standout goalie – and baseball in the summer, Sabo idolized Gordie Howe and Al Kaline. But baseball was his first love.

“I was Al Kaline, always Al Kaline,” Sabo told the Dayton Daily News. “All I knew was that all I ever wanted to be was a big league baseball player. Like Al Kaline.”

Sabo helped Detroit Catholic Central High School win a state championship in 1979, the same year the Reds won their sixth National League West title of that decade. They would not advance to the postseason again until Sabo was their regular third baseman in 1990.

“I followed baseball (in 1979) but I hated the Reds,” Sabo told the Dayton Daily News in 1990. “I was an American League fan, loved the Tigers. I hated Cincinnati.”

The Expos selected Sabo in the 30th round of the 1980 MLB Draft. But Sabo opted for college and enrolled at the University of Michigan. Three years later, Sabo was one of the best collegiate third basemen in the country and was named to 1983 College World Series All-Tournament team as a junior. He played on the same side of the infield as future Hall of Famer Barry Larkin, and the duo led Michigan to a third-place finish at the CWS.

The Reds selected Sabo in the second round of the 1983 MLB Draft as the 30th overall pick. This time, fresh off the College World Series in Omaha, Neb., Sabo signed and was sent to Class A Cedar Rapids, where he hit .274 in 77 games and was named the team’s Most Valuable Player.

In 1984, Sabo was promoted to Double-A Vermont of the Eastern League where he hit .213 with just five home runs in 125 games. He battled a shoulder injury and also had a strained relationship with manager Jack Lind.

“I was built up as a good player, but from what people saw of me in 1984, I stunk,” Sabo told the Burlington (Vt.) Free Press. “I’ve been a power hitter all my life. Last year, I don’t know what in the world happened.”

He returned to Vermont in 1985, where he once again teamed up with Larkin – who was selected by the Reds with the fourth overall pick in the 1985 MLB Draft. In his second season with Vermont, Sabo hit .278 with 11 homers and 46 RBI in 1985, earning a berth on the Eastern League All-Star team.

Sabo was promoted to Triple-A Denver in 1986 and hit .273 with 10 homers and 60 RBI. He was invited to the Reds’ Spring Training camp in 1987 – but many thought that Lenny Harris, who played at Vermont in 1986, was the team’s third baseman of the future.

“(Sabo) shows potential as a hitter,” Brian Granger, the Reds’ assistant director of scouting and player development, told the Cincinnati Enquirer, “with decent pop in his bat.”

The Reds moved their Triple-A team to Nashville in 1987, and Sabo hit .292 with seven home runs and 23 steals in 91 games with the Sounds while missing most of the final two months of the season with a left leg injury. Sabo started the year hot and was hitting .343 in early June.

“I’m not doing anything different than I’ve been doing,” Sabo told the Tennessean. “I’m just getting more hits.”

Despite appearing in fewer than 100 games, Sabo was named Nashville’s Most Valuable Player.

Sabo came to the Reds’ Spring Training camp in 1988 fighting for a backup infielder spot. But when starting third baseman Buddy Bell sprained his knee, Sabo stepped in and started on Opening Day. Bell returned a week later but quickly injured the knee again, and Sabo returned to the starting lineup and never looked back.

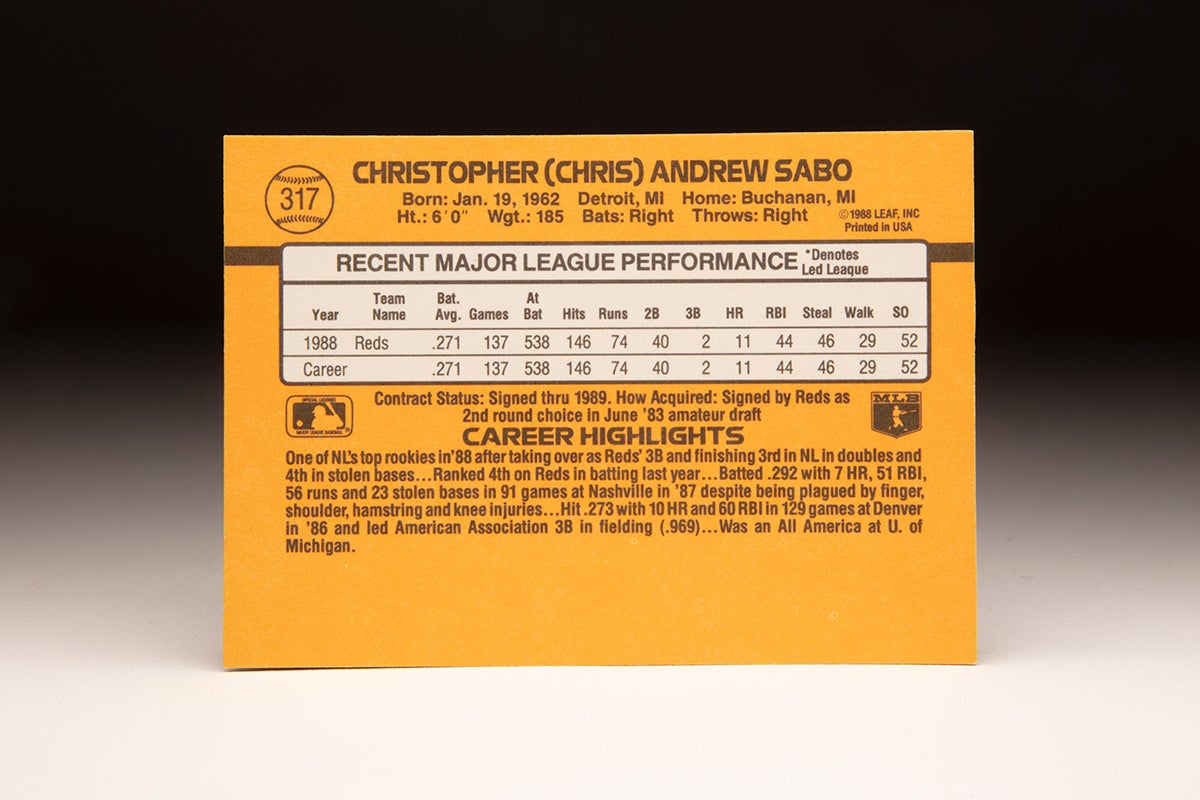

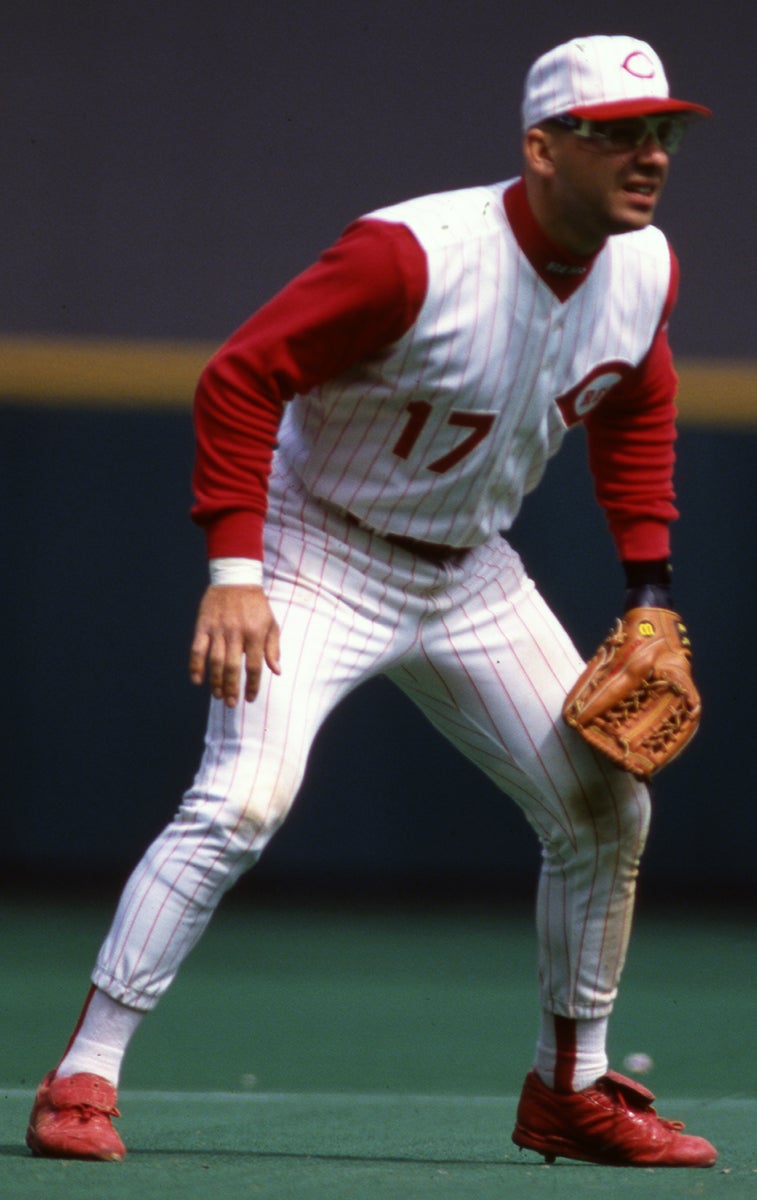

Reds manager Pete Rose tagged Sabo with the nickname “Spuds,” saying that Sabo resembled the dog Spuds MacKenzie in a popular beer advertisement of the time. He was hitting as high as .324 in late June before cooling off to finish at .271 with 40 doubles, 11 homers, 44 RBI and 46 steals. He was the only rookie to appear in the 1988 All-Star Game, which was played at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium.

“I wore out, flat wore out,” Sabo told the Dayton Daily News about his second-half struggles. “And I’m not worried about the so-called second-year jinx, or sophomore jinx, or whatever it is called.

“I’m working hard. No one is gonna out-work me. I’m working out six to seven hours a day. I don’t want to wear out and get injuries (in 1989).”

Sabo’s work ethic was respected around the league, and he was rewarded by being named the National League’s Rookie of the Year for 1988. His 5.1 Wins Above Replacement figure was the top tally among all NL rookies.

“I don’t feel secure at all,” Sabo told the Associated Press after learning he won Rookie of the Year honors on Nov. 1, 1988. “I’ve always felt that way. As far as I’m concerned, I’ve got to win a job in ’89 like I did this year.”

But Sabo wanted more than just a job – or even another league award.

“I wasn’t expecting it, but it’s nice when it happened,” Sabo told the Dayton Daily News about his Rookie of the Year honors. “If I didn’t get it, I wasn’t gonna quit. What I really want is a World Series ring.”

A ring was in Sabo’s future, but first he would have to endure a difficult 1989 season. He started the year slowly at the plate, hovering around the .230 batting average mark through May and going silent with the media contingent as a result. He pushed his average back to .260 by the end of June but was then sidelined for two months by a knee injury that required surgery.

Sabo finished the season – one that saw Rose given a lifetime suspension for gambling – batting .260 with six home runs, 29 RBI and 14 steals in 82 games.

But Sabo believed the best was yet to come, especially with the addition of new manager Lou Piniella.

“(Piniella) is a real tough individual and he knows what it takes to be a winner,” Sabo told the Urbana (Ohio) Daily Citizen during an offseason stop at Upper Valley Joint Vocational School in Piqua, Ohio, following the 1989 season. “He’s been on several championship teams and he said he wants to win it all.

“I think we’re going to win the World Series if we stay healthy.”

Few others predicted a championship for the 1990 Reds, but the team led the National League West wire-to-wire as Sabo hit .270 with 95 runs scored, 25 home runs, 71 RBI and 25 steals. He earned his second All-Star Game berth and led all NL third basemen in fielding percentage with a .966 mark – matching the same finish and number as he did in 1988.

The Reds faced the Pirates in the NLCS – the fifth time the teams had met in the League Championship Series. Sabo was a combined 2-for-12 (.167) in the first three games but played a key role in the pivotal Game 4, giving the Reds a 2-1 lead in the fourth inning with a sacrifice fly and then untying the game (Pittsburgh scored a run in the bottom of the fourth) with a two-run home run in the seventh.

Pittsburgh cut the lead to 4-3 on a Jay Bell home run to lead off the bottom of the eighth, and after Andy Van Slyke flied out Bobby Bonilla ripped a ball to center field that came within a foot of going over the fence. Reds center fielder Billy Hatcher crashed into the wall trying to catch the ball, and the ball caromed back into center field as Bonilla sprinted for third base. But left fielder Eric Davis was backing up on the play and gathered in the ball before unleashing a laser beam toward Sabo, who dropped to his knees in front of the bag to corral the one-bounce throw and tag out Bonilla.

The Reds scored an insurance run in the top of the ninth as Cincinnati won 5-3 to take a 3-games-to-1 series lead.

“I didn’t think there was any chance of getting Bonilla,” Sabo told the Cincinnati Enquirer. “I was screened out as he came around, and the ball came out of nowhere. The ball suddenly appeared to me, and I just reacted and put (the tag) down.”

Sabo had one hit in the last two games as Cincinnati lost Game 5 but won Game 6 to advance to the World Series. Waiting for them were the defending champion Oakland Athletics, who entered the Fall Classic as a massive favorite. But the Reds won Game 1 by a score of 7-0 as Sabo’s two-run single in the fifth inning plated the game’s final runs and proved to be the knockout punch.

Sabo had three more hits in Game 2, including a one-out single in the 10th inning off Dennis Eckersley that pushed Billy Bates to second base. Bates would score the winning run when Joe Oliver followed with another single, giving Cincinnati a 2-games-to-none lead.

Then in Game 3, Sabo’s second-inning solo home run opened the scoring before he followed with a two-run blast an inning later – he became the 30th player to hit two home runs in a World Series game – as the Reds scored seven times to break open a game they would win 8-3. Sabo also set a record for third basemen in a nine-inning World Series game by handling 10 chances without an error.

Game 4 seemed almost anticlimactic as Sabo had three more hits to help Cincinnati win 2-1 and sweep the series.

Sabo batted .563 (9-for-16) with two home runs and five RBI. Incredibly, he wasn’t even the leading hitter on his own team as Hatcher hit .750 (setting a World Series record). Jose Rijo, who posted two wins and allowed just one run over 15.1 innings, was named the World Series Most Valuable Player.

Arbitration-eligible for the first time, Sabo agreed to a one-year deal worth $1.25 million for 1991.

“I think I can do better this season, hit for a higher average,” Sabo told the Dayton Daily News during Spring Training in 1991. “(The 1990 World Series is) history. Ancient history.”

But the Reds were unable to repeat in 1991 due to injuries and off-the-field issues. Sabo, however, appeared in a career-best 153 games while hitting .301 with 26 home runs, 88 RBI and 19 steals while being named to the All-Star Game for the third time, including his second appearance as a starter.

Sabo and the Reds finalized a one-year deal worth $2.75 million for 1992. But he sprained an ankle legging out an infield hit in the second game of the year, and the joint bothered him all season. He hit .244 with 12 homers and 43 RBI in 96 games, then agreed to a one-year deal worth $3.1 million for 1993 – with free agency looming after the season.

After hitting .259 with 21 home runs and 82 RBI in 148 games, Sabo expressed a desire to return to the Reds – despite a trying season for him and his teammates where the club went 73-89.

“I’ve played baseball since I was a little boy, and this is the only year of my life that it hasn’t been fun,” Sabo told the media after the Reds’ final game of the 1993 campaign. “I’m glad it’s ending today, and I’ve never said that before.”

But despite the team’s on-field record in 1993, Sabo publicly announced that he would accept a million-dollar pay cut in the first year of his new contract in exchange for a multiyear deal with the Reds.

“I thought I was being pretty nice,” Sabo told the Cincinnati Post. “I was there 11 years, and I never had one contract dispute. I never haggled over anything.”

But with the Reds insisting they did not have the money to issue long-term contracts, Sabo had to look elsewhere. He turned down a reported two-year deal with the Mets worth $6.4 million before signing a one-year deal with the Orioles worth $2 million that included incentives that could have been worth another $400,000. But Sabo was unable to reach those incentives due to injuries – including a sore back – and a strike-shortened season that saw him hit .256 with 11 homers and 42 RBI in 68 games.

When the labor dispute was settled, Sabo signed a one-year deal with the White Sox worth $550,000 – and another $550,000 in incentives – to be their designated hitter. But he was only able to appear in 20 games before being released on June 5. He finished the year with the Cardinals, appearing in just 25 games at the big league level while hitting .238.

On Dec. 7, Sabo brought his career full circle when he returned to the Reds.

“I’ve always considered myself a Red, even when I played for these other teams the last couple years,” Sabo told the Cincinnati Post. “The past couple years haven’t been very pleasant. It doesn’t seem like these other teams liked me as much as the Reds used to.”

Sabo started at third base on Opening Day and drove in three runs in Cincinnati’s 4-1 win over Montreal. But he battled injuries as well as a corked-bat controversy – when his bat broke in a July 29 game against the Astros, cork flew out; Sabo claimed he was using a borrowed bat – and he appeared in his last game of the season on Sept. 2 before a right knee injury sidelined him for the season. He finished with a .256 batting average in 54 games.

He went to Spring Training with the Mariners in 1997 – Piniella was Seattle’s manager – but was released on March 19, ending his career.

Over nine big league seasons, Sabo hit .268 with 214 doubles, 116 home runs, 426 RBI and 120 stolen bases. He left a trail of dirty uniforms along the way – remnants of the hustling spirit that powered his career.

“My dad always said: ‘As long as you produce, you’ll be wanted,’” Sabo told the Associated Press after winning the NL Rookie of the Year Award in 1988. “When you stop producing, you’re gone.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum